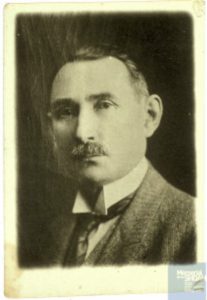

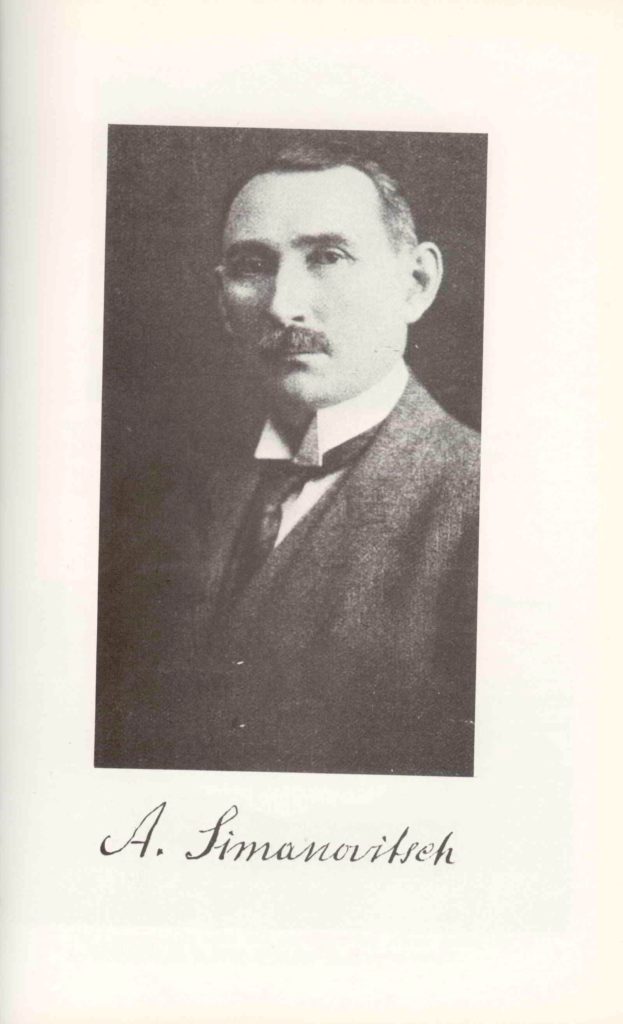

Aron SIMANOVITCH, 1872-1944

The life of Aron Simanovitch was researched by a group of three students from the French International High School in Vilnius, Lithuania, where Aron Simanovitch was born in the years between the wars.

A famous figure

Aron Simanovitch’s story is quite special, since he was well-known for having once been “Rasputin’s secretary”. He has been the focus of several books, and he wrote his own autobiographical account, Rasputin and the Jews. His great-niece, Delin Colon, drew inspiration from his work as she wrote Rasputin and The Jews: A Reversal of History, published in 2011. However, the autobiographical narrative must be treated with the utmost caution, because even in his lifetime Aron Simanovitch was criticized for his “fanciful” remarks. At times Aron Simanovitch’s imagination, or that of his admirers goes too far: in his 1971 book The Conspirator who saved the Romanovs, Gary Null, who later became known as a radio host, a proponent of “alternative” therapies, anti-vaccine campaigns and conspiracy theories, even claims that Aron Simanovitch saved Nicholas II and his entire family from being executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918!

To reconstruct the biography of Aron Simanovitch, the work did not involve much searching for documents, as it did for the other deportees, but rather taking a critical look at the mass of information already available. The work of Anastasia Rahlis, who published a long article in Russian on her blog “Арон Симанович и сыновья” (“Aron Simanovitch and his sons”), was very helpful in this regard. In it, she compares Aron Simanovitch’s statements with information from a number of other sources.

In addition, while exploring Aron Simanovitch’s life after the First World War, we also found the police file compiled about him at the time of the Third Republic, which was provided by the organizers of the project, very helpful, as was information gathered from genealogy sites such as familysearch.org and ancestry.com, not to mention some contemporary press articles found on newspapers.com.

Lithuanian origins … broadly speaking

According to French documents, Aron Simanovitch was born on February 15, 1872 in Vilnius, Lithuania, which at that time was part of the Russian Empire and the western periphery of which was home to a very large Jewish population. This is related to the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which at the end of the Middle Ages and in the Modern Era, stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Ukraine and opened its doors to the Jews, who had been expelled from many other European countries. Through their craftmanship and commercial know-how, they contributed a great deal to the development of the country. Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, was even known as the “Jerusalem of the North”.

However, we were unable to find Aron Simanovitch’s birth certificate in the Jewish registers from the city of Vilnius, which are all supposedly held in the Historical Lithuanian State Historical Archives and are available on the Mormon genealogical website familysearch.org. Also, in the inter-war period, Aron Simanovitch used Lithuanian identity documents, which eventually turned out to be forged. Along with several other deportees officially “born in Vilnius” but who do not appear in the city’s Jewish registers, Aron Simanovitch was probably born in the Vilnius region rather than in the city, at least in a very broad sense. In 1908, according to the Saint Petersburg city registers, Aron Simanovitch claimed to come from the city of Mozyr, in Belarus. At the time of the 1897 census, the city had just over 8000 inhabitants, of which more than 70% were Jews. They thus accounted for a large proportion of the urban population in the “Residence Zone” allocated to them in the West of the Tsarist Empire, where they often lived grouped together in predominantly Jewish towns or districts known as shtetl.

Depending on the source documents, Aron Simanovitch’s father was called Simon, Samuel or Simkhov. He apparently had numerous children from several marriages, and in private conversations Aron Simanovitch spoke of twenty-one siblings. We know the identity of only three of them, his sister Libba, who died shortly after giving birth to a child in 1889, his older brother Chaim-Nessel, born in 1868, who became a precious metal dealer, and a certain G., who emigrated to the United States.

Aron Simanovitch seems to have spent his youth in Mozyr, learning about business and the jewelry trade with his brother Chaïm-Nessel. He undoubtedly learned to read and write, despite not having attended school for any length of time. Later, once he became famous, he was reputed to be “illiterate”, poorly educated and to speak Russian badly.

Mozyr at the end of the 19th century, https://mozyrxxvek.blogspot.com/2015/01/blog-post_87.html

From one town to another

In 1901, at the latest, Aron Simanovitch settled in Kiev, Ukraine, still within the Residence Zone assigned to Russian Empire’s Jewish population, and there he opened a jewelry store.

At that time, Aron Simanovitch was already married and was the father of several children. His wife Teofilia, born June 18, 1876, also came from a large family involved in the world of construction and craftsmanship. Some of her family members lived in St. Petersburg, outside the Residence Zone, under the protection of the Minister of Finance, Serge Witte, who was seeking to develop Russia’s economy and industry. The couple had at least five children: Siemen/Simon, seemingly born on April 2, 1896 (the favorite son and the only one mentioned several times in his father’s memoirs), then Ioann/Jean, born on March 5, 1897, Maria, born around 1899, Solomon/Salomon, born on April 11, 1901, and Clara, born in Batoum, Georgia, on October 17, 1901. The name of Iosif also comes up frequently, but he could have been a nephew who was living close to Aron Simanovitch.

Kiev during the Belle Epoque

In 1902, Aron Simanovitch settled alone in Saint Petersburg initially and then brought his family to join him following the Kiev pogrom of October 13-20, 1905. This took place during the 1905 revolution, when nationalist, monarchist and anti-Semitic groups, known as the “Black Hundreds”, attacked the Empire’s Jewish population. In October 1905, more than 600 pogroms erupted, principally in the Ukraine, where a hundred or so Jews were killed in Kiev and 2500 died in Odessa. Aron Simanovitch rushed back to Kiev, where he discovered his store ransacked, windows broken and bodies of his loved ones on the street. He then used his connections in the police, along with bribery, to evacuate his family to St. Petersburg, where, without special permission, Jews were not allowed to live. It was not within the Residence Zone in the western part of the empire, which had been established at the end of the 18th century.

The 1905 pogroms were far from the first to occur in the Tsarist Empire, particularly in Ukraine. Following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, the first wave of pogroms had swept through the Residence Zone, forcing a large number of Jews to flee Russia: more than two million people left between 1881 and 1914. In 1881, Aron Simanovitch was not in Ukraine, where the pogroms were the most widespread and violent, but according to him, the trauma of the Kiev pogrom marked a turning point in his life. From then on, he said, he became an advocate, intervening on behalf of the Jews with the Russian high society that he frequented.

Victims of the pogrom in Kiev, Kiev Jewish Metropolis, a history 1859-1914, Natan Meir, 2010

The “Court Jeweler”?

In St. Petersburg the family lived on Pushkin Street and then moved to a neighboring property, just across the courtyard, at 8, Nikolaevskaya Street. At the time, it was a neighborhood of craftsmen, storekeepers and domestic servants. The last place they lived in the capital was a six-room apartment with a monthly rent of 215 rubles, the equivalent of a manual worker’s salary. The family moved in the city’s wealthy social circles, and after the war Aron Simanovitch told the French authorities that between 1905 and 1908, he and his family had often visited Nice, where they stayed in a large apartment in the Hotel Cécil. He was still a jeweler by trade, had a store selling “gold items” and described himself as a master watchmaker and a dealer in precious metals and diamonds.

In the capital Aron Simanovitch went to theaters, cabarets, horse races and gambling houses. He is even said to have founded several card gambling rings, which were frequented by high society. This was how he attracted a new clientele, to whom he supplied not only jewelry but also “financial advice”, loaning money and charging interest. Aron Simanovitch claimed to have thus gained access to the heart of the imperial court, via the Wittgenstein princes, who were the bodyguards of Emperor Nicholas II. He said he was then introduced to Empress Alexandra, to whom he supposedly sold jewelry at low prices in order to secure her protection and recommendations. Nevertheless, Aron Simanovitch is mentioned neither in the diaries of the Empress or Tsar Nicholas II, nor in any of their correspondence.

The Imperial family: Tsar Nicolas II, Tsarina Alexandra and their children

On the other hand, his reputation as a gambler, making huge gains and sometimes spending whole days, without sleeping, playing cards is backed up by numerous witnesses.

“Rasputin’s secretary”

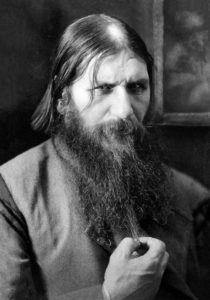

It was Rasputin who supposedly cured him, at least temporarily, of his gambling addiction Grigori Rasputin was a mystic and a healer, who managed to secure the protection of many members of Russian high society, including the imperial family, in particular the Tsarina, whose son, Tsarevich Alexis, suffered from hemophilia. He represented the typical image of a “pilgrim”, who left faraway Siberia following his early mystical visions and led a nomadic lifestyle. A colorful character, who claimed to be a monk but had a wife and children, he had a reputation for debauchery.

Rasputin was presented to Nicholas II and his wife on November 1, 1905, shortly after Aron Simanovitch’s family moved to St. Petersburg. Aron Simanovitch, however, recounted that he had already crossed paths with the healer in Kiev at the beginning of the century, only to meet him again by chance in St. Petersburg. Even though Aron Simanovitch claimed to have known the pilgrim for many years, it seems that he did not really become close to him until 1914 or 1915, when Rasputin’s influence with the imperial family grew stronger with the outbreak of the Great War.

From the end of 1915 onwards, Aron Simanovitch met Rasputin regularly and became known as one of his “secretaries”, despite his reputation for being “illiterate” and the fact that Rasputin did not actually have any secretaries and always replied to his correspondence personally. Nevertheless, various accounts confirm that little by little Aron Simanovitch became the “monk’s” main “secretary”, or at least was close to him, working in his shadow, rendering various services and, according to such accounts, joining in his late-night parties. Aron Simanovitch took this opportunity to intervene on behalf of his Jewish friends, who were seeking to settle outside the Residence Zone, to obtain places in educational establishments despite the quotas that had been placed on Jews at the end of the 19th century, to escape persecution or simply to get out of prison. This was confirmed by witnesses at the time, even though Aron Simanovitch perhaps exaggerated when he spoke of the “thousands” of Jews saved by his intervention, his influence on the Imperial Court’s decisions regarding the Jewish question, and their rejection of a separate peace agreement with Germany. However, his activities were not limited to the Jewish question: several unsavory characters from the gambling houses, among them fraudsters connected with the sugar industry, gravitated around Simanovitch.

The “secretary” also took advantage of his protector’s talents as a healer. Having learned that his son, Ioann Simanovitch, had long been suffering from Sydenham’s chorea, an incurable neurological problem that had paralyzed his left arm, Rasputin supposedly invited the patient to his home and healed him by simply laying his hands on his forehead and blowing into his eyes. At any rate, this was the story that Ioann used to tell after the Second World War.

For his eldest and favorite son, Siemen/Simon, Aron Simanovitch had big plans for the future: he wanted him to study at the Polytechnic Institute. In order to escape the number limit placed on Jews, Rasputin made several applications on his behalf. Presumably it worked, since after the war Simon presented himself as an “engineer”. As for Ioann, he studied at the Higher Institute of Commerce in Petrograd.

His downfall

In 1915-1916, however, although Rasputin’s influence was increasing, German offensives began to undermine the Tsarist empire and, along with it, the status of the Simanovitch family. Aron’s brother, Chaim-Nessel and his entire family took refuge with his brother in Petrograd, the new ” Russianized ” name for St. Petersburg. And in areas near the front, the Jews, a population that the Tsarist authorities considered “unreliable”, were forcibly evacuated.

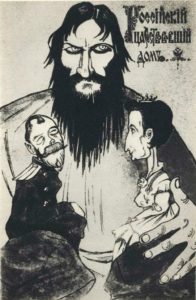

Secondly, Rasputin, Aron Simanovitch’s protector, was facing mounting opposition within the Imperial Court, from which a number of princes and ministers were trying to keep him away. One example of his influence on the Imperial couple was the pressure he exerted on them to replace Justice Minister, Aleksandr Makarov, with a more conciliatory figure, Nicholas Dobrovolsky. This idea seems to have been floated by Aron Simanovitch himself.

1916 cartoon depicting Rasputin’s hold on the lmperial couple

The plots against Rasputin were, on occasion, aimed at his “secretary”. International newspapers mention Aron Simanovitch’s arrest on February 22, 1916, on the orders of the Minister of the Interior, and his subsequent banishment to Pskov. It required the intervention of Rasputin, the Tsarina, and seemingly even Nicholas II himself, to get him released from prison and back to Petrograd. This episode alone confirms the close relationship between Aron Simanovitch and Rasputin.

This incident came at a time when rumors were already circulating in the capital about a forthcoming assassination attempt on Rasputin, allegedly instigated by the Minister of the Interior. Aron Simanovitch approached his contacts in high society to try to prevent the murder and urged Rasputin to save himself, but to no avail.

Rasputin was finally assassinated on December 17, 1916, while he was visiting Prince Yusupov. When rumors of the assassination began to spread, Aron Simanovitch took part in the search for the body. His son Simon found one of Rasputin’s galoshes near a bridge shortly before the discovery of his body in the Neva River. The Simanovitch family also took care of Rasputin’s two daughters, Maria and Varvara. An apartment was found for them and the Tsar granted them a pension.

Since he showed too little commitment to the investigation of the assassination, the Minister of Justice, Aleksandr Makarov, was finally replaced by Nicholas Dobrovolsky. Dobrovolsky proved to be less conciliatory than expected towards the somewhat “shady” individuals who gravitated around Rasputin and Simanovitch, but was open to the idea of improving the legal status of the Jews in the Empire.

Aron Simanovitch’s victory came a little too late, however, since just two months later, during the Revolution in February 1917, Tsar Nicholas II was overthrown. Aron Simanovitch was then arrested on the orders of the Investigative Commission of the Duma, the Russian Parliament. At the beginning of his interrogation, he claimed that he did not know Rasputin, that he had not been his secretary and that he was not even able to write, which was untrue. His apartment was raided, and everyone present, including members of his family, Rasputin’s two daughters, their French governess and several other people, was arrested. His family was released the following day, but Aron Simanovitch was detained for several more days, spending time in various prisons including the Peter and Paul Fortress. According to his own account, he was eventually released in exchange for a payment of 200,000 rubles and an undertaking to leave the capital, although this is not confirmed by any other source. Either way, he stayed on in Petrograd.

Meanwhile, the provisional government exhumed Rasputin’s corpse, which had been buried in a newly built chapel near the Summer Palace, and had it incinerated in a boiler at the Polytechnic Institute, the very same school that Aron Simanovitch had so desperately wanted his son Simon to attend.

A long nomadic period

Aron Simanovitch remained in Petrograd until October 1917, when the Bolsheviks took control of Russia and introduced a communist regime. White armies then fought with the Bolshevik Red Army and tried to overthrow the regime. The civil war lasted from 1918 to 1921-1922, and Russia was ravaged not only by the fighting, but also by economic chaos, famine and typhoid fever.

In 1918, Ukraine had declared itself to be an independent country and Aron Simanovicth fled to Kiev. According to his memoirs, he managed to take with him a large number of diamonds, hidden in a plaster cast on his arm, on a train carrying Ukrainian invalids. Shortly afterwards, his family joined him.

However, anti-Semitism was on the increase in the Ukraine, with armed gangs carrying out pogroms in 1918-1920 that were even more deadly than those of 1881-1914. The Simanovitch family therefore left for Odessa, where Denikin’s White army and his French allies were stationed. Then in April 1919, when the French army withdrew, they took refuge in Novorossiysk, a Russian port on the Black Sea, which was also under Denikin’s control. Living conditions there were poor, and according to Aron Simanovitch’s account, one of his sons caught typhoid fever.

Next they left for Batoum in Georgia, and then for Turkey, before settling in Germany. Meanwhile, his brother, Chaïm-Nessel, took refuge in Romania, where he practiced as a dentist and was joined for a while by Ioann. Aron Simanovitch settled in Berlin, probably in 1921, in the early years of the Weimar Republic. The political environment there was very turbulent, and the inflation rate was high. Aron Simanovitch tried to relaunch his business using the stock of diamonds that he had brought with him from Russia, but was unsuccessful.

In 1923, his son Simon married a girl from Romania and on April 21 of the same year, Aron Simanovitch and his wife left for the United States. His brother G. Simanovitch had been living in New Jersey for some time and a nephew, who used the Americanized name of Harry Linowitz, was living in New York. As “Rasputin’s former secretary”, he was interviewed by several American newspapers.

Pu Aron Simanovitch then returned to Europe. The family eventually settled in Paris on August 10, 1924, and Ioann joined them there. His wife, Teofilia, would appear to have died, at the latest in 1929. From 1928 on, Aron, Ioann and his wife Marie lived in a furnished apartment at 9, rue Roy, in the 8th district. In 1936, while the sons were living elsewhere with their wives, Aron Simanovitch was living at the Nouvel Hotel, at 49 rue La Fayette and then in 1937 at 27 rue Buffault, both in the 9th district.

The writer of Rasputin’s memoirs

When Aron Simanovitch spoke to the authorities, in particular when he traveled on transatlantic liners, he claimed to be a journalist, a writer and Rasputin’s memorialist: this was the reputation that he had been seeking to acquire ever since his unsuccessful business venture in Berlin.

In 1927, Aron Simanovitch supported Maria Rasputin when she sued Felix Yusupov, who had just published a book about his involvement in Rasputin’s murder. She took the case in the French courts and sought a large sum of money in compensation, but her claim was dismissed. The following year, in 1928, Aron Simanovitch published “Rasputin: The Memoirs of his Secretary”, in Russian, probably written with the help of someone else. In it, he defends the Monk, especially with regard to his intervention on behalf of numerous Jews, at the request of his secretary, but he also exaggerates somewhat the duration and intensity of the relationship between himself, the jeweler, and Rasputin:

“For many years I was with Rasputin, day and night. I was the one who knew him best. I can safely say that he did not particularly believe in the strength of his relationship with the Tsar. It often seemed to me that he did not feel credible; that he was not at ease. The thought that he might one day have an important role to play made him look to the future. He was not so much afraid of his death as of his downfall and the inevitable consequences he would face. Rasputin was very conceited, so the thought of his downfall bothered him more than his death. He tried to calm himself by believing in his “strength”, with good reason, as I have previously mentioned. Tormented by doubt and anxiety about the future, Rasputin turned to me for friendly advice and support. He considered me to be a good mathematician, with great experience and a practical mind. He believed in me and clung to me. I also felt an attachment to him. I never saw anything bad in him and he did no harm to others. It was not his fault that Nicholas II was a weak emperor. With my help, he helped thousands of people and, thanks to his kindness, saved many of them from poverty, death and persecution. I shall never forget Rasputin, and therefore I have no right to condemn him or even to judge him in general. There are no flawless people, but, in my opinion, Rasputin was more honest than all those who gathered in his apartment.”

The book was translated into many other languages, including French in 1930.

An unsavory reputation

Aron Simanovitch’s activities, however, were far from being confined to literature: in France, the former “secretary” soon attracted the attention of the police. As early as 1924, visits by German officers suspected of espionage were reported, as well as suspicions of links with Soviet spies. Also, Aron carried a Lithuanian passport, but the Lithuanian authorities informed the French police in 1937 that it was a stolen document, and that Aron Simanovitch did not have Lithuanian citizenship.

Standing up for Rasputin’s memory was clearly not sufficient to provide a living for his family, since in August 1926, Aron Simanovitch was arrested on the border between Italy and Austria, into which he was attempting to smuggle diamonds and other precious objects.

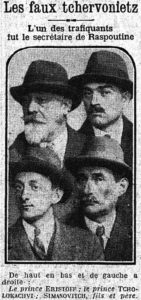

In February 1927, he was arrested in the Ternes district of Paris, together with his son Salomon, as they were trying to exchange chervonets, a new Soviet currency introduced in 1922, for 15,000 francs (which would be worth around 9,000 dollars today). The banknotes were forged. They had been supplied by a Georgian count, Nestor Eristov, an old acquaintance whom Simanovitch had introduced to Rasputin, who in turn blamed a former colonel in the Tsarist army, Cholokashvili. They too were arrested. All of them claimed to have been convinced that the banknotes were genuine. Aron Simanovitch was nevertheless imprisoned from February 18 to November 18, 1927, and then released. The investigation then led back to a certain Shtengeli, who portrayed himself as a Georgian nationalist spreading counterfeit Soviet currency in order to weaken the USSR. In September of the same year, the counterfeit press was discovered in Germany. Aron Simanovitch was eventually acquitted on July 8, 1930, and again in January 1933, after the Soviet bank, Gosbank, lodged an appeal.

Period press clipping taken from Anastasia Rahlis’ blog

However, in 1928, Aron Simanovitch was arrested again, this time for having signed a blank check for 8,000 francs. As a result, he was imprisoned for two weeks and sentenced in 1931 to pay one franc as a token gesture to the recipient of the check. He appealed and was ultimately acquitted by the Court of Rouen in 1936.

The fact that Aron Simanovitch appealed against such a light sentence was perhaps because it was coupled with a ban on frequenting gambling houses, which accounted for a significant part of his income, as it had in St. Petersburg. He was a seasoned gambler, in circles such as “Opera”, “Frolic’s” and the “Racing Circle”. In 1926, a police report described him as an “inveterate night owl and reveler… He is seen as a ruthless operator with no scruples about how to obtain money to meet his needs.” His sons shared his passion for games and the gambling business. Even though they led their own lives in the 1930s, Simon was expelled from the gambling halls on October 13, 1934 due to irregularities, and Simon and Salomon ran two kiosks in Paris, one trading in precious objects and the other in musical instruments. Simon probably traveled a lot: his police file mentions that he was expelled from Nazi Germany in 1933 or 1934. Maria danced in cabarets, sometimes in Paris and sometimes in Romania, as did Rasputin’s daughter Maria. It is even possible that they shared the same accommodation in Romania.

Pending his appeal and return to the world of gambling, in late 1928 Aron Simanovitch and his daughter Maria received an insurance payout of 100,000 and 200,000 francs respectively, after having been run over by a car on the Champs Elysées. This money may have been reinvested, since in the 1930s, the police recovered large sums of money collected from the United Kingdom, from shares in British and American oil.

The aftermath of the Stavisky case

In 1934, Aron Simanovitch and his son Simon were even cited in the Stavisky case, which shook the Third Republic and sparked riots among extreme right-wing groups in front of the National Assembly on February 6.

Alexandre Stavisky was a Jewish financier from the Kiev government, who was found guilty of significant embezzlement while compromising high-ranking French officials and politicians. On January 8, he “committed suicide” but the case did not end there. On February 20, the mangled body of the Judge, Albert Prince, head of the financial section of the Paris Public Prosecutor’s Office, who was in charge of the case, was found tied to the railway tracks and near Dijon. He had arrived in Dijon the same day, on the same train as Simon Simanovitch, who was on his “honeymoon” with his second wife. Simon was questioned by the police, as was his father.

The three Simanovitch sons were named in the press as possible accomplices in the murder. Extreme right-wing publications became involved, and Léon Daudet wrote an article in L’Action française calling for the arrest of Simon Simanovitch and his father, as well as the manager of Frolic’s, Max Garfunkel.

Press photo of Simon Simanovitch in the 1930s, from Anastasia Rahlis’ blog

Aron Simanovitch left for the United States on October 31, 1934, perhaps to escape the scandal, and also to try to reclaim some money. He arrived on November 6. His brother, G., who had been an entrepreneur before the October 1917 revolution, had deposited two million gold rubles in the subsidiary of an American bank in Petrograd, which were later confiscated by the Bolshevik regime. But in 1933, the United States and the Soviet Union began a diplomatic relationship, with the former demanding that the latter pay back any debts owed to American citizens. G. Simanovitch, who had since died, had been naturalized as an American citizen, so this was the reason that the family hoped to be able to reclaim the looted money. Aron Simanovitch’s efforts were unsuccessful, however. While in the United States, he also got involved in the case of Anastasia Tchaikovsky, who claimed to be the daughter of Emperor Nicholas II, who had escaped execution by the Bolsheviks in 1918. Aron, who described himself as a great specialist on the Romanovs, asserted that she was a fraud.

Aron Simanovitch returned to France on September 28, 1935, but the whiff of scandal lingered on. The French authorities considered expelling him, and an order was signed on May 26, 1937. But a number of medical certificates and, above all, the fact that Aron Simanovitch was now stateless prevented his deportation: no country was willing to admit him, not even Lithuania, which deemed his identity documents to be false. In March 1939, it was suggested that Aron Simanovitch be placed under house arrest in the Cantal, but this was never acted upon. His sons, Simon and Salomon, were also issued an expulsion order, then granted a three-month residence permit by way of a reprieve.

Life during the Occupation

When the Second World War broke out, the Simanovitch family promptly lost its freedom.

Solomon was arrested by a patrol during the night of September 13, 1939, while impersonating a civil defense inspector. He was sentenced to four months in prison. He was later reunited with his father in a camp for stateless persons. When the Third Republic came to an end, several camps had been set up for different types of foreigners: Spanish refugees, German and Austrian citizens, stateless persons, etc.

Following the armistice in 1940, the establishment of the Vichy regime, and the occupation of a large part of the country by the German army, some of the internees remained imprisoned, while others were released. This did not, however, preclude them from being victims of anti-Jewish raids later on. On March 23, 1943, Solomon was deported on Convoy 52, which left Drancy for the Sobibor extermination camp, where he was killed.

Aron Simanovitch was arrested on the night of July 20, 1944 at 39, rue Richter, in the 9th district of Paris, and then transferred to Drancy camp. The Drancy search log shows that Aron Simanovitch had 3600 francs on him at the time, which was quite a large sum compared to those of other prisoners. It would be equivalent to about 700 dollars nowadays. Rasputin’s “secretary” was among those deported on Convoy 77, which left on July 31 and arrived at Auschwitz on August 3. Given that he was 72 years old at the time, Aron Simanovitch was probably sent to the gas chambers as soon as he arrived, as were the majority of the deportees on the convoy.

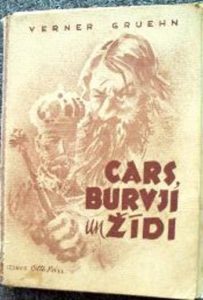

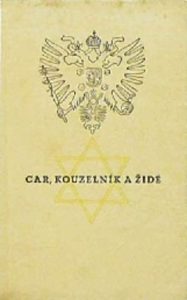

The Nazis thus killed Aron Simanovitch in the end, even though they took inspiration from his memoirs for propaganda material that was published in several languages in 1942-3: The Czar, the Magician and the Jews. The story of Aron Simanovitch, who, via Rasputin, professed to have had a great influence on the treatment of Jews in Russia, is a perfect illustration of those used in “Jewish conspiracy theories”, which often involve the alleged ability of Jews to manipulate governments around the world.

The sons who escaped

Two of Aron Simanovitch’s three sons, Simon et Ioann, survived the Holocaust.

Between 1940 and 1942, Simon managed to escape to Liberia, in Africa. His business flourished rapidly and he was closely involved in government circles and with President Tubman: in the 1950s he chaired the country’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry, which he even represented at the International Labor Organization conference, where he was elected to the Board of Management. In Monrovia, Simon was also appointed Honorary Consul to Israel. He died on October 28, 1958.

Ioann apparently lived through internment in the camps for stateless persons, although his story is somewhat unclear. He was reportedly sent to a Polish extermination camp to be shot, but was liberated en route by the British, before ending up in a camp for displaced persons after the war. His son Henri, born in 1927, escaped the roundup by hiding in the South of France during the Occupation, perhaps with his mother, and after the war he settled in Switzerland. Ioann, like Simon, he left for Liberia in 1948. He opened a restaurant, called “Rasputin” in honor of his healer, in Monrovia. There he hosted members of the Tubman family, as well as a number of well-known Soviets, including various diplomats and, in 1962, the cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. He died in 1977.

Little is known about what became of the Simanovitch daughters.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Superbe bio pour un parcours vraiment atypique. Bravo pour ce travail !

Bonjour,

Je suis la fille de Micheline Solomoniks, fille de Maria Solomoniks née Simanovitch, elle-même fille d’Aron et Teofilia Simanovitch

Je peux vous fournir des compléments d’information et surtout apporter quelques corrections:

par exemple

– c’est ma grand-mère, Marie ou Maria, qui est née le 17 octobre1899 (mais ma grand mere s’est rajeunie de 2 ans sur ses paierrs francais!),

– sa soeur Clara est née le 6 mai 1905 !

– La 1ere femme de Jean s’appelait Bella, et non Marie! (la seconde, épousée au ibéria s’appelle Truda)

Ma grand-mère a aussi eu une vie bien mouvementée: elle a aussi cotoyé les familes présidentielles Libériennes Tubman et Tolbert, par qui elle a d’ailleurs été décorée chevalier Grand Commandeur de l’ordre “Liberian Human Order of African Redemption” ).

Elle a épousé Grégoire simanovitch et a eu une seule enfant, ma mère, en 1934. Elle est décédé en juillet 1989.

Sa soeur Clara a vécu à Berlin où elle s’est marié avec Abraham Milstein (naturalisé en Henry Morton aux USA), puis aux Etat-Unis où elle a été naturalisé en Clara Morton et y est décédée sans descendance.

Bien cordialement,

Carol Galy (née Solomoniks)