Jim ANKAR

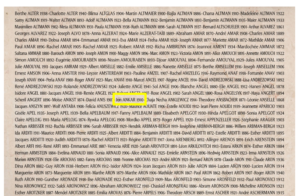

Photo of “Jim Ankar”

Source: Memorial de la Shoah

This biography was written in the style of a historical investigation by students from the Ayguesvives junior high school in the Haute-Garonne department of France

Introduction

We are 38 students from two 9th grade classes at the Jean-Paul Laurens secondary school in Ayguesvives, in the Haute Garonne department.

We “met” Jim Ankar through the Convoy 77 European project, which aims to write the biographies of people who were deported on July 31, 1944 on the last convoy to leave the Drancy camp for the Auschwitz killing center in Nazi-occupied Poland. Our mission was to retrace this man’s past by carrying out a thorough historical investigation.

Every week, on Fridays, we met Jim as we would a fellow traveler. During our weekly “Convoy 77” workshop, led by our history and geography teacher and documentalist, we followed in his footsteps and traced his journey through Poland, Belgium, France and the Ukraine. We teased out his story through a range of historical documents that allowed us to reconstruct some fragments of his life.

Our biographical investigation

We first came across Jim in four documents from the Shoah Memorial in Paris, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 team.

The first of those was a photograph one of the slabs that makes up the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial. It includes the name “Jun Ankar” and the year in which he was born, 1910:

Inscription on the Wall of Names showing Jun Ankar’s name and date of birth (1910)

His name is on slab n°2, column n°1, row n°2

Source: The Shoah Memorial in Paris (1944-2-BD)

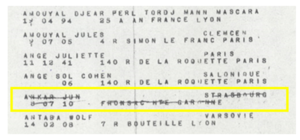

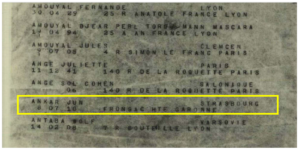

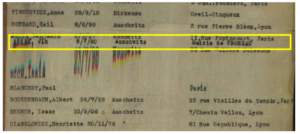

The second document that we were given is an extract from the list of people deported on Convoy 77, which left Drancy camp on July 31, 1944.

Map of the route across Europe taken by Convoy 77

Source: https://deportation.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en&itemId=5092649

At the end of July 1944, the situation in Paris was very volatile. The Allies, who had landed on June 6, were advancing towards Paris. On July 20, an attack on Hitler and a coup attempt failed. The leaders of the Gestapo, who had been arrested by the Wehrmacht, were released.

Alois Brunner, the commander of Drancy camp, took advantage of the confusion to continue his murderous madness to the very end. He sent his men into the children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews) in and around Paris to “round up” 330 children, 18 of them infants.

Convoy 77 left Drancy on July 31, 1944 carrying people of 37 different nationalities. It arrived at Auschwitz on August 3. Of the 1321 deportees on board, 740 were sent to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived at the camp

The camp was liberated by the Red Army on 27 January 1945. 214 prisoners survived forced labor, abuse and deprivation.

Jun Ankar’s name appears on the list of people deported on Convoy 77. His date and place of birth are listed as being July 8, 1910 in Strasbourg. His last known address was in the town of Fronsac in the Haute-Garonne department of France. We then began to wonder why he was deported: was Jun a Jew, a Resistance fighter, a Communist, a political opponent, a homosexual, or a gypsy?

The original list of people deported on Convoy 77, which left the Drancy camp on July 31, 1944, bearing the name of Jun Ankar, born on 08.07.1910, in Strasbourg, living in Fronsac (Haute-Garonne department)

Source: Shoah Memorial in Paris (C77_2)

Fronsac, a town in the south west of the Haute-Garonne department

Source: http://francegeo.free.fr/ville.php?nom=fronsac-31

We were intrigued by the fact that his was the only name on the list that was crossed out. We therefore came up with some hypotheses: Was it a mistake? Might he have escaped? Did he die before the train set off or during the journey to Auschwitz? The questions were mounting up……

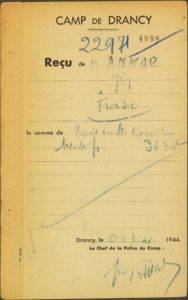

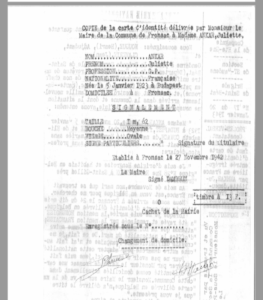

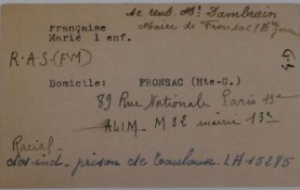

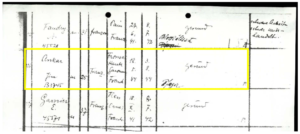

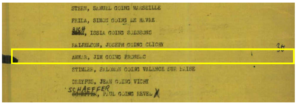

The third document, provided by the Shoah Memorial, is the receipt from the search notebook issued on May 22, 1944 by the chief of police at the Drancy camp. The first name, which is hardly legible, appears to be “Jim”, the surname is Ankar, and the town of Fronsac is mentioned. This is the record that led us to nickname our deportee “Jim”. The page bears the number 22971 which refers to his prisoner number at Drancy. The prisoners were searched upon arrival and any cash they had on them was confiscated: the record shows that Jun was carrying 3630 francs. This was a considerable amount of money, which aroused our interest. What could it mean? Why did he have so much money on him? Was he planning to escape?

Receipt n° 4898 from search logbook n°140 at Drancy camp, dated May 22, 1944 made out to Jim Ankar from Fronsac for the sum of 3630 French francs and signed by the chief of police at the camp.

Source: Shoah Memorial in Paris (CF140_4898)

Since we had more questions than answers, we were naturally interested in what the Shoah Memorial website had to say, and one page in particular caught our attention:

While it includes some of the information we already have (his surname, his first name “Jun”, his date and place of birth, his address in Haute-Garonne, the number of the Convoy on which he was deported, the place and date of departure of the Convoy, the camp to which he was deported), there is also some new information: first names (Jum, Jim, and Binem) and a different surname (Fajwisiewicz). These names are described on the site as having been “rejected”, which made us wonder what this meant: Why would they have been rejected? This raised even more questions: the plot began to thicken. Our investigation then took a completely different turn and gathered speed: was our man Jun or Jim Ankar, or was he Jum or Binem Fajwisiewicz? Could he have had two different names? Was one of them an alias? If so, why? Which was his real, original name? Where did his second identity spring from? Did it match that of a real person or did he make it up? If he borrowed it from someone else, who was it? And why? Questions, questions and more questions. There were increasing numbers of leads.

Amidst this flurry of hypotheses, we found the final detail given on the page very moving: we realized that Jim had survived. He was therefore one of the 214 Convoy 77 survivors. It was a great relief to know that he had lived through the Nazi barbarism.

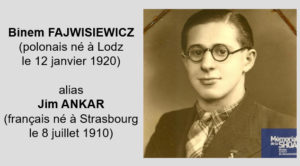

We were fortunate in that the final item from the Shoah Memorial was a photograph of Jim. It was deeply moving to actually see the face of this young man, well-coiffed, with round glasses, wearing a suit and matching shirt and tie.

”Who were you, Jim ?”

Source: © General Archives of the Kingdom of Belgium –Aliens Police department (KD_0017)

The staples on the top of the photo led us to believe that it was probably taken to add to an official document; could it be an identity photo? Was it taken to obtain a specific administrative document? We therefore wrote to the Shoah Memorial to find out if they knew the provenance of the photo. They told us that it had been sent to them as part of a partnership with the Kazerne Dossin in Mechelen, Belgium. We therefore contacted the Belgian Archives service, and they explained where it came from.

They told us that about 90% of the photos of the deportees had come from the Foreigners’ Police department’s archives. In accordance with the German decree of October 28, 1940, all Jews were required to apply for registration in a special register kept by the Belgian local government staff in the town where they lived. Children under 15 years of age were included on the cards of the head of the household. These photos were provided by the immigrants when they first arrived in Belgium. They all had to be checked by the Foreigners’ Police in order to obtain visas, passports, residence permits, work permits and identity cards etc. It is important to understand that these photos were generally taken several years before the people were deported.

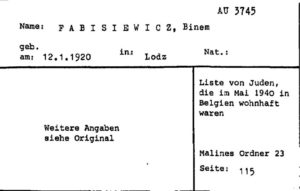

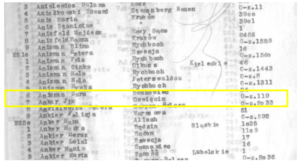

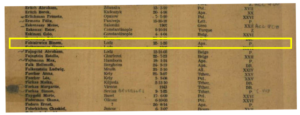

This photo confirms that Jim was indeed a Jew and that he was living in Belgium in 1940. This is confirmed on the list of Jews living in Belgium in May 1940, which we obtained from the German archives in Bad Arlosen: one card bears the name of Binem Fabisiewicz, born on January 12, 1920 in Lodz, Poland, and whose registration number 3745 is preceded by the letters “AU”, which stand for Auschwitz:

Source: Bad Arlosen archives, International Tracing Services (dossier 23, page 115)

We were stunned to realize that our deportee did indeed have two identities: Jim Ankar and Binem Fabisiewicz. This meant that we had to deal with an alias! But which was his true identity? And how could we distinguish it from the fictitious one?

We then asked the Strasbourg municipal archives service for a copy of the birth certificate to verify whether a certain Jim Ankar had indeed been born there on July 8, 1920. Their answer was unequivocal: “We wish to inform you that the requested record cannot be found in our registers for the date in question”.

The French National Archives service in Pierrefitte then told us that their research on Mr. Ankar was initially focused on the so-called “Jewish file”. Their searches in the files for the camps at Drancy, Beaune and Pithiviers were also unsuccessful, unfortunately (F/9/5674-F/9/5777).

Since we could find no official record of Jim, was Binem our “real” deportee? As our work sessions progressed, our “Jim” was gradually becoming “Binem”…

To find out for sure, we contacted the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels and they sent us this very informative document:

A page from the Belgian « Register of Jews » (KD_0008)

Published with the kind permission of the Jewish Museum of Belgium, in Brussels

This page, which is taken from volume 66 of the register of Jews and was made out on November 28, 1940, mentions Binem Fabisiewicz, who was born in Lodz, Poland on January 12, 1920. We see that he moved from Lodz to Belgium in 1931. A Polish national of Jewish faith, he is listed as a leatherworker and as the husband of Hélène Herskovic.

This register lists in detail the addresses at which Binem lived at the beginning of the war: 179 rue Emile Féron in Saint-Gilles (i.e. his parents’ address), 62 rue du Collecteur in Anderlecht from February 25, 1941, and he then returned to rue Emile Féron, at number 28 this time, as of May 3, 1941.

The 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital area: Binem lived in Saint-Gilles and then in Anderlecht before returning to Saint-Gilles.

Source: Wikipedia

The document also outlines his genealogical background: Binem was the son of David, born in Brzeziny in 1883, and Rachela born in Tuszyn in 1877[1]. He was the grandson of Lejzir Mindel Fabisiewicz, born in Zyrankow, and Dczabozaporski Rapir, born in Brzeziny, all of whom were Jews. In May 1940, the Nazis created a ghetto in a part of Brzeziny. This was liquidated on May 14, 1942, and most of the residents were then transferred to another ghetto in Lodz[2].

Map showing the location of the Polish municipalities of Lodz (Binem’s birthplace), Brzeziny (Binem’s father’s birthplace), and Tuszyn (Binem’s mother’s birthplace)

Source: https://www.viamichelin.fr/web/Cartes-plans/Carte_plan-Wielkopolskie-Pologne

We appreciated getting to know our deportee a little more intimately: with the references to his parents, he became a little more familiar to us. This Polish Jew was becoming increasingly tangible. He was now an integral part of our group. We were eager to learn more. But where should we look next? Which threads of the past should we try to tease out?

One particular detail then came to mind. Our history and geography teachers explained to us that the Convoy 77 team assigns a deportee to a school based on its geographical location. We therefore had to uncover this very distant link between Binem and ourselves. This is why we needed to visit the Departmental Archives service in Toulouse in order to complete our investigation.

The Departmental Archives service in Toulouse, at 11 boulevard Griffoul Dorval.

Photo published with the kind permission of the Departmental Archives service in Toulouse.

We discovered that this amazing place contains no less than 26 linear miles of archives of all kinds, the oldest of which dates back to the 9th century.

Shelves in the Departmental Archives building in Toulouse

Our own photos

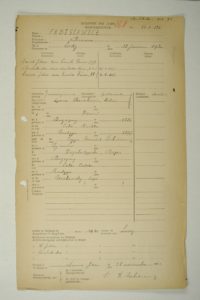

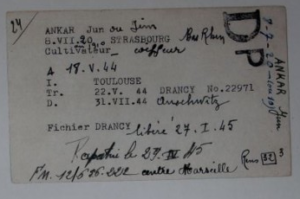

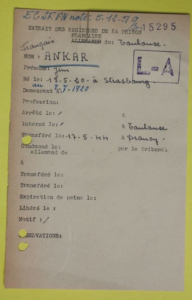

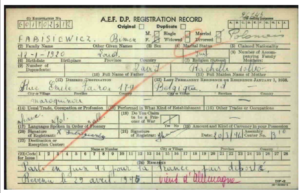

By chance, a file from the Délégation Principale de Toulouse (Main Delegation of Toulouse) [3] in the name of Jim Ankar is in the archives. The letters “DP” on the top left of the file mean that he was deported because he was a Jew, rather than a Resistance fighter:

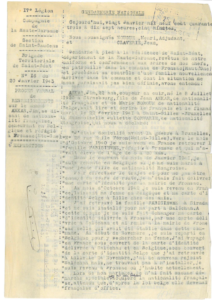

The first page of the Main Delegation of Toulouse file in the name of Jim Ankar

Source: Departmental Archives service in Toulouse (box n°. 6863 W 6)

It was therefore with considerable emotion that we opened the box containing this file, which bears the number 6863 W 6. The first document we found was a certificate dated February 21, 1945 from the Haute Garonne Departmental Directorate of the Ministry of Prisoners of War, Deportees and Refugees. From the lists held by the Departmental Directorate, this attestation certifies that Jim Ankar, born on July 10[4] 1920 in Strasbourg, was indeed arrested on May 18, 1944 in Toulouse and was then transferred to Drancy. This certificate, signed by the Head of the Administrative and Technical Services, specifies that it was issued “pour servir et valoir ce que de droit”, meaning “to serve for all legal intents and purposes”.

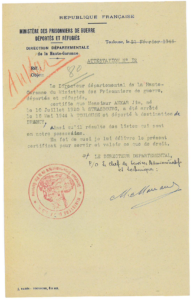

The second page of the Main Delegation of Toulouse file in the name of Jim Ankar

Source: Departmental Archives service in Toulouse (box n°. 6863 W 6)

Another version of this document, also dated February 21, 1945 but considerably less legible, is attached to the file. A handwritten addition states that Jim “never came to collect this attestation”:

The third page of the Main Delegation of Toulouse file in the name of Jim Ankar

Source: Departmental Archives service in Toulouse (box n°. 6863 W 6)

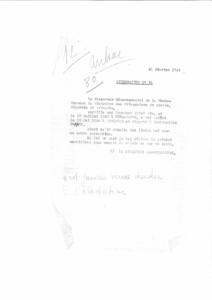

Another document (not dated, unfortunately) in this file was issued by the Regional Delegation of the Ministry of Prisoners of War, Deportees and Refugees:

The fourth page of the Main Delegation of Toulouse file in the name of Jim Ankar

Source: Departmental Archives service in Toulouse (box n°. 6863 W 6)

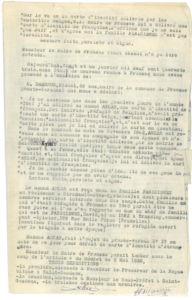

While this document, in the name of Jim Ankar, born on July 8, 1920 in Strasbourg, confirms that he was arrested on May 18, 1944 in Toulouse, it also provides the location of the arrest and some additional information: Jim was rounded up at the Saint-Cyprien railroad station in Toulouse and was arrested by the Gestapo. The reason for the round-up is not mentioned. It says that the prisoner had two children and that he was assumed to have left the Drancy camp for Auschwitz on July 30, 1944. This date appears to be an error, given that Convoy 77 left Drancy on July 31, 1944.

The line beginning “latest news” includes the date “July 30 (1944) at (or “from”?) Drancy camp – nothing known since that date.” No transfers to camps in Germany are listed. The deportee’s home address is listed as Fronsac in the Haute-Garonne department and his occupation is described as “leatherworker”.

The person who should receive this information is listed as “Madame Ankar at 41 rue des Récollets in Toulouse”. But was this Mrs. Ankar Jim’s wife or was she his mother?[5]

The stamp visible at the bottom left of this page caught our attention: It includes the cross of Lorraine and the words “COSOR Haute-Garonne”. It is proof that this page came from the Archives of the Comité des œuvres sociales de la Résistance (Resistance Social Works Committee). “The social works of the Resistance organisation was formed in secret, as a reaction to the initial arrests of members of the movement, in order to help the victims of German repression and their families. […] It was “a national organization dedicated to the rescue of all victims of the clandestine battle” […] “with the task of helping, irrespective of race, opinion or religion, all those in distress as a result of Nazi oppression”[6].

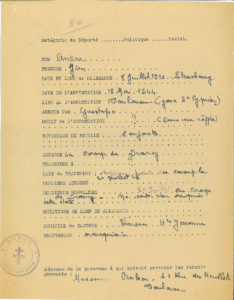

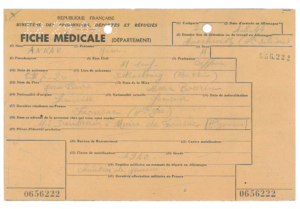

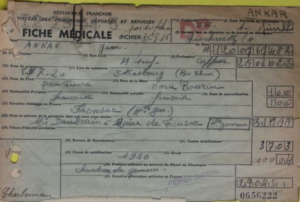

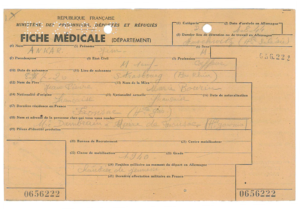

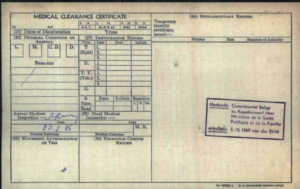

The following document, also from this file in the Departmental Archives in Toulouse is a departmental medical card issued by the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees:

The fifth page of the Main Delegation of Toulouse file in the name of Jim Ankar

Source: Departmental Archives service in Toulouse (box n°. 6863 W 6)

This fairly detailed medical card was drawn up when he returned after having been deported, at the repatriation center in Marseille, as shown by the number at the bottom right: 0656222, which matches the reference “FM 12/656 222” found on the National File card. It is perforated on the top left corner with the number 12 29 04 5.

It includes the date of Jim’s arrival in Germany as August 4, 1944, after a five-day journey from Drancy (which he left on July 31). The category “DP”, which stands for “déporté politique”, or “political deportee”, confirms the fact that he was arrested because he was a Jew. The last place of detention or work in Germany is listed as “Auschwitz”. It says that Jim was married and had one child. His occupation is listed as barber (rather than leatherworker, which had been mentioned previously). It gives his date of birth as July 8, 1920 in Strasbourg in the Haut-Rhin department of France. It also includes the first names and surnames of his father (Jean Pierre), his mother (Marie Bourin), the fact that he held French nationality (from birth and on the date on the card) and his last residence in France (Fronsac in Haute-Garonne department).

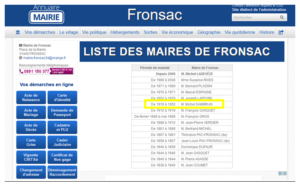

We noticed one particularly interesting entry: the name and address of the person where the deportee intended to go next: it reads “Mr. Dambrain (name spelled incorrectly) at the town hall of Fronsac (Haute-Garonne)”. Our research has confirmed that the mayor of Fronsac from 1919 to 1952 was indeed Michel Dambrun:

Source: https://www.annuaire-mairie.fr/mairie-fronsac-31.html

The medical record lists 1940 as the year of Jim/Binem’s mobilization. His military status at the time he left for Germany states that he had been at a “chantier de jeunesse”, a type of military youth camp. The Chantiers de la Jeunesse Française (CJF) organization was a French paramilitary organization that operated from 1940 to 1944. Responsible for the training and supervision of young French people, it was strongly influenced by the values of the National Revolution championed by the Pétain government [7].

The first to be mobilized were all young French people aged 20 living in the non-occupied zone (classes of 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943 and 1944). This tends to confirm Jim’s true birth year as being 1920. When the work camps began in 1940, the mobilization period lasted 6 months, which then increased to 8 months (following a decree dated January 18, 1941)[8]. Perhaps Jim went to the Pyrenees-Gascony camp, which fell under the jurisdiction of Toulouse? We found no records to prove this, however.

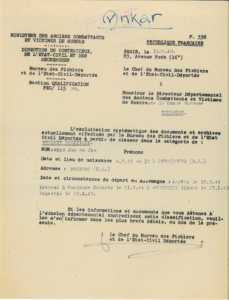

The final document in the Departmental Archives file is the most recent record that we found relating to Jim/Binem. It is dated March 19, 1948 and was issued by the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War. It is signed by the head of the Bureau des Fichiers et de l’Etat-Civil des Déportés (Records and Civil Status of Deported Persons office) and is addressed to the Departmental Director of Veterans and Victims of War of the Haute-Garonne department:

The sixth page of the Main Delegation of Toulouse file in the name of Jim Ankar, issued by the French Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War

Source: Departmental Archives service in Toulouse (box n°. 6863 W 6)

This document confirms that Jim/Jun Ankar was categorized as a political deportee. Once again, his date of birth is ambiguous and still poses a problem: it was July 8, but was it 1910 or 1920? It gives the date and circumstances of his departure for Germany: he was arrested on May 18, 1944, interned in Toulouse (whereabouts exactly is still not mentioned, unfortunately), deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1945, liberated on January 27, 1945 and repatriated on April 29, 1945 (again, there is no mention of where this took place) [9].

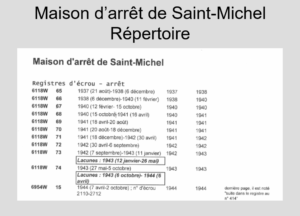

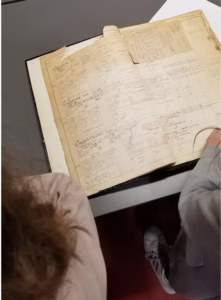

Our visit to the Departmental Archives also enabled us to ascertain that Jim/Binem was not interned in two of the detention centers in Toulouse. We therefore checked the register of the Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse:

Source: photo from the Departmental Archives service in Toulouse

The old Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse, as it is today

Source: our own photo

Students looking at the register of the Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse

Source: our own photo

The register of the Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse

Source: our own photo

We are surprised by the quality and intensity of the inks used in this impressive register, which is more than 80 years old: the green and red are still vivid.

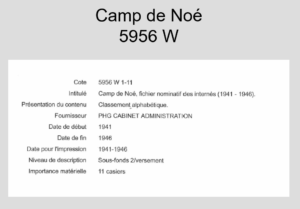

We also looked at the register of the Noé camp:

Source: photo from the Departmental Archives service in Toulouse

Map showing some of the internment camps in the South of France

Source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_d%27internement_fran%C3%A7ais

By looking at these registers, we were able to confirm that Jim was not interned in neither the Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse, nor in the Noé camp, which was located about twenty miles south of the city. So where was he interned? We discovered several other prisons in Toulouse, such as Furgole, Vernet, and the Gallieni barracks. We discovered that the largest number of prisoners, and the least dangerous in the eyes of the Germans, were placed in the Cafarelli barracks. Regrettably, we didn’t have the time to pursue these leads to look for any records relating to Binem.

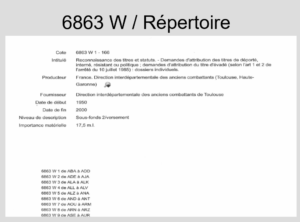

With the guidance and advice of Mr. Sébastien Corbière, an archivist, we continued our investigations at the Departmental Archives service in Toulouse, where we examined the applications for the status of political deportees and internees and Resistance fighters submitted to the Prefecture of Haute-Garonne:

Source: photo from the Departmental Archives service in Toulouse

Unfortunately, our research proved fruitless. We realize, nevertheless, that our visit to the Departmental Archives was very informative and enabled us to conclude our investigation. To have the opportunity to consult these documents, which are more than 80 years old, was a great privilege. The way that they are handled so delicately, and have been preserved in such good condition, really impressed us.

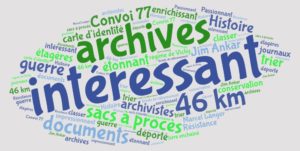

Word cloud created by the 9th grade students following their visit to the Departmental Archives in Toulouse

Word cloud created by the 9th grade students following their visit to the Departmental Archives in Toulouse

Much to our surprise, a few weeks after our visit, the Departmental Archives service got back to us. A history student who was going through documents in another part of the building miraculously unearthed another file on Jim! We were absolutely thrilled to discover some additional information about him!

What the student had found was an official information record[10] drawn up by the police in Saint-Gaudens, a town in the west of the Haute-Garonne department[11]. This report provides numerous details and we found it really quite moving to read Jim/Binem’s own words for the very first time.

Sergeant Henri Nougue and Jean Claverie (whose rank is not mentioned) were on uniformed foot patrol in Fronsac on January 20, 1943. On the orders of their superiors, they went to check on a family that had recently arrived in the village and whose circumstances did not seem to them to be very clear. They interviewed Jim Ankar, who claimed to be a French citizen, resident in Belgium, who had taken refuge in Fronsac. Jim said he was 22 years old, a leather cutter, born on July 8, 1920 in Strasbourg, the son of Jean Ankar, a French citizen, and Marie Boroum, a Belgian citizen. He said he could read and write French and Flemish. He said he was married on February 22, 1941 in Saint-Gilles, a town near Brussels, to Miss Juliette Corwarie, who was Hungarian. We therefore wrote to the Civil Status Department in Saint-Gilles to request a copy of this marriage certificate. Here is their reply: “We have checked the marriage registers from 1931 to 1950 and we have not found any marriage record in the name of the people concerned.” This would seem to be further confirmation that Jim Ankar was indeed a fake identity and that he was really Binem Fabisiewicz.

During his interview, Jim explained to the gendarmes that before the war he had lived in Brussels, at number 28, rue Emile Féron in the Saint-Gilles district. He said that in about October 1940, he had come to France to be with the Fabisiewez family[12], who were refugees in Fronsac and who had raised him from the age of 5 to 20. We were amazed by this. Why would he have been taken in by this family for 15 years? Was he an orphan? Was he already a refugee at the time?

He said that sometime in January 1941 he went back to Belgium, where he got married to a Hungarian girl. And so as to be able to make the journey and to avoid any trouble along the way, he had obtained an identity card from the town hall of Fronsac.

He said he came back to France in October 1942, leaving his wife in Belgium and his Belgian identity card with friends in Lille. He then returned to the Fabisiewez family in Siradan (in the Hautes-Pyrénées department) and settled in the nearby village of Saléchan. He says that at that time he exchanged the identity card issued in Fronsac for a new one, issued in Saléchan. He claims to have given back the previous identity to the town hall in Fronsac.

At the beginning of November 1942, he said, he left for Belgium to collect his wife. He traveled through France with the identification card issued by the town hall in Saléchan and through Belgium with his Belgian identity card that he had retrieved in Lille.

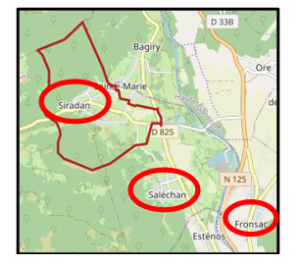

Map showing the villages of Siradan and Saléchan (in the Hautes-Pyrénées department) and Fronsac (in the Haute-Garonne department) that were mentioned by Jim Ankar in the police report from Saint-Gaudens

Source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siradan#/media/Fichier:Siradan_OSM_01.png

He said that he returned to Saléchan on November 24, 1942, but since he could not find a place to live, he returned to Fronsac, where he was still living when he was interviewed by the Saint-Gaudens police.

He explained that when he married his wife, he did not request French nationality for her, because according to Belgian law, she became French by default. He also said that it was on the basis of the card issued by the Belgian authorities that the mayor of Fronsac issued him a French identity card. He stated that he was not Jewish and that, as far as he was aware, the Fabisiewez family was not Jewish either. As the mayor of Fronsac was not available at the time, the Saint-Gaudens police were unable to interview him to confirm or deny Jim’s claims.

The following day, January 21, 1943, the police returned to Fronsac to interview the mayor, 59-year-old Michel Dambrun. He told them that in early 1941, he had issued a French identity card to a man named Ankar. Saying that he was a refugee from Belgium, Jim had shown him a Belgian identity card bearing the words “French nationality”. We then began to wonder who could have added the words “French nationality”? Might Jim have written it himself in order to avoid any complications? It was on the basis of this card that the mayor had issued him with a French card.

Michel Dambrun said that in November 1942, Jim Ankar returned to the Fronsac with his wife and produced an identity card issued by the town hall of Saléchan, where they had lived for some time. His wife had no identity papers but, according to Jim, she was a French citizen because he was French and she was married to him. The mayor therefore issued Mrs. Ankar a French identity card.

The police report then states that Jim Ankar was taken in by the Fabisiewez family, who lived in Siradan in the Hautes-Pyrénées department, several members of which were being held in internment camps. According to the police, this family, which had taken refuge in Fronsac in 1940, appeared to be “of Jewish race”, based on the name of the head of the family, David Fabisiewez, a grocer who was born in 1883 in Brzeziny and had previously lived at 179 rue Emile Féron in Brussels (this is mentioned in the register of refugees compiled by the police at that time). If we have understood correctly, Jim had in fact moved in with his father!

Page 1 of the official report drawn up on January 20, 1943 by the Saint-Gaudens police following their interview with Jim Ankar

Source: record N° 2054 W 1502 from the Departmental Archives in Toulouse

Page 2 of the official report drawn up on January 20, 1943 by the Saint-Gaudens police following their interview with Jim Ankar

Source: record N° 2054 W 1502 from the Departmental Archives in Toulouse

The police then interviewed Jim Ankar’s wife, Juliette Ankar, who was 20 years old, was born on January 5, 1923 in Budapest in Hungary, lived in Fronsac, and was the daughter of Michel Corwarie and Elisabeth Cowach, both of whom were Hungarian citizens. She was married and had no children. She could read and write French. She was not working at the time. In view of her status, she was the subject of an official report[13] drawn up on January 20, 1943 in connection with the following offenses: not being in possession of a foreign national’s identity card and unlawful entry into France.

She declared during her interview that she lived at number 28 rue Emile Féron in Saint-Gilles, near Brussels, Belgium. She confirmed that her husband, who was in France, came to Belgium in November 1942 to pick her up. They arrived in Fronsac on November 24, 1942. She said that she had an identity card issued in Belgium. When they got married, the word “Hungarian” on Juliette’s card was crossed out and replaced by the word “French”, since Belgian law stipulates that a woman automatically adopts her husband’s nationality. As a result, she believed she was already a French citizen and thus had not made any effort to acquire French nationality. She said that in order to avoid any trouble, she had obtained an identity card from the mayor of Fronsac since she was now living in the village. The mayor issued her a French identity card on the basis of the card issued in Belgium. Is it possible that the mayor of Fronsac, in doing this, was acting in a spirit of resistance in an attempt to protect the Ankars? The report states that Juliette was in bed during the interview because she was pregnant at the time. The police were therefore unable to arrest her, even though she was living in France illegally.

Page 1 of the official report drawn up on January 20, 1943 by the Saint-Gaudens police following their interview with Juliette Ankar

Source: record N° 2054 W 1502 from the Departmental Archives in Toulouse

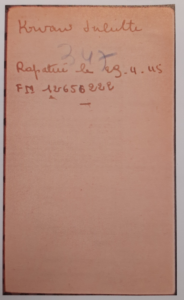

On the back of the report is a copy of the French identity card issued to Juliette Ankar on November 27, 1942 by the mayor of Fronsac. The description includes her height, which was 5’6″, her mouth, which was said to be “average” and the shape of her face, which was “oval”. There were no distinctive features. The words “change of residence” are written at the bottom of the page:

Back of Page 1 of the official report drawn up on January 20, 1943 by the Saint-Gaudens police following their interview with Juliette Ankar

Source: record N° 2054 W 1502 from the Departmental Archives in Toulouse

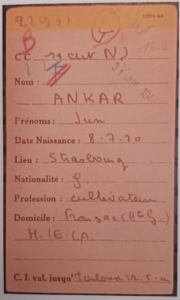

The French National Archives kindly sent us Jun Ankar’s record card from the Drancy File [14] which came from the Seine Police Headquarters “individuals” file[15]. It was made out in the name of Jun rather than Jim (might this have been an error in copying or spelling?) when he arrived at the Drancy camp. It states that his date of birth was July 8, 1910 or 1920 (the year is not easily readable), his birthplace was Strasbourg, his nationality was French, his occupation was farm worker and his residence as Fronsac (in the Haute-Garonne department). The note at the bottom, “Toulouse 22.05.44, refers to the place from which he had been transferred and the date on which he arrived in Drancy. His internee number, 22971, was added to the top of the card later. The “L” at the top, with a circle around it, stands for “Liberated” and was added when he returned to France.

The front side of the card from the Seine Police Headquarters’ “individuals” file, kept in box ref. F/9/5632.

Source: Seine Police Headquarters “individuals” file, from the French National Archives

The back of the form states that Jim was repatriated on April 29, 1945, and lists the name Juliette Kovaw (which is presumably a misspelling of Juliette’s mother’s maiden name: she was Elisabeth Cowach). The back of the form states that Jim was repatriated on April 29, 1945, and lists the name Juliette Kovaw (which is presumably a misspelling of Juliette’s mother’s maiden name: she was Elisabeth Cowach). The note “FM 12 656 222”, which is the number of her medical record, was added when she was repatriated to France:

The back of the card from the Seine Police Headquarters’ “individuals” file, kept in box ref. F/9/5632.

Source: Seine Police Headquarters “individuals” file, from the French National Archives

Next, we contacted the Shoah Memorial Archives service, which holds an archive box dedicated to Jim Ankar. It is labelled AC 27 – P – 941 and corresponds to the previous folder n° 1891. It originally came from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. This box contains six documents that were an invaluable contribution to our research.

File taken from the French National Register of Deported Persons[16]

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, ref. AC 27 P 941

The first item in the Drancy file is a small card in the name of Ankar Jun, born July 8, 1920, in Strasbourg in the Bas-Rhin region, who was working as a farm laborer. Some information has been added by hand: the first name “Jim,” the year “1910″, (twice), the region “Bas-Rhin” and the occupation “hairdresser”. These additions confirm our man’s double identity, and illustrate the confusion between the two. The “DP” stamp on the side of the card again suggests that he was a political deportee (i.e. that he was deported because he was Jewish).

It shows that Jim/Binem was arrested on May 18, 1944, interned in Toulouse, transferred to Drancy on May 22, 1944, where he was assigned the registration number 22971[17]. He was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 on Convoy 77. He was liberated from the camp on January 27, 1945 and returned to the repatriation center in Marseille, France, on April 29, 1945.

The Drancy internment camp, near Paris

Source: Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-B10919,_Frankreich,_Internierungslager_Drancy.jpg

The front of the card states that Jun Ankar was a French citizen. It says that he was married and had one child. It confirms that he lived in Fronsac in the Haute-Garonne department. The reference to an “personal file at the Toulouse prison” refers to his arrest. The adjective “racial” has been added by hand: it refers to the fact that he was deported because he was Jewish.

The Drancy File

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service ref. AC 27 P 941

The Drancy file contains a medical form that reminds us, strangely enough, of the one we found in the Departmental Archives in Toulouse: it is indeed very similar. Judge for yourselves.

Medical card from the Drancy file (front)

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service ref. AC 27 P 941

The fifth item from the dossier on Jim Ankar from the Main Delegation of Toulouse

Source: Departmental Archives in Toulouse (box N° 6863 W 6)

The card in the Drancy file is dated August 31, 1945 and was also issued by the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees.

The information entered is exactly the same (surname, first name, marital status, occupation, date and place of birth, parents’ names, nationality, last known address, the address to which the deportee intended to go, mobilization class, military rank and his status as a political deportee). We also note that the date of birth is crossed out in a similar manner, the words “Haute-Garonne” are framed in the same way, and these two medical records bear the same number: 0656222. Might they be duplicates?

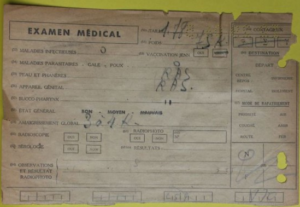

The back of the medical card from the Drancy file

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service ref. AC 27 P 941

The back of this medical form details the deportee’s physical condition: a medical examination was conducted at the repatriation center in Marseille. Even though this form was not filled out in full, we can see that Jim was 5’8″ tall and weighed 165 pounds when he was liberated. We were amazed to see that the form says that Jim had only lost 7 or 8 pounds, which did not seem very much to us. He was not suffering from any infectious, contagious or parasitic diseases (scabies, lice etc.), and his body (skin, genitalia etc.) and his hair and nails had not been harmed. His general state of health was considered “good to average” since only the word “bad” was crossed out. The fact that he was in fairly good health is quite surprising given that he had just spent six months in a killing center. We were relieved by this, but also puzzled by it.

The last document from the Drancy file is an “extract from the registers of the French prison in Toulouse”:

Extract from the registers of the French prison in Toulouse (Drancy file)

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service ref. AC 27 P 941

It includes Jim Ankar’s name, his nationality, which was French, his place of birth, which was in Strasbourg, and the place where he was interned, which was Toulouse[18]. The date of his transfer to the Drancy camp is given as May 17, 1944. So, three documents from the Departmental Archives in Toulouse and one from the Bad Arolsen Archives[19] list May 18, 1944 as the date on which he was arrested and May 22 as the date on which he was transferred to Drancy. The date of his transfer to Drancy on this particular document is therefore incorrect. The date of his transfer to Drancy on this particular document is therefore incorrect. Our attention was also drawn to the two different dates of birth: Initially, May 18, 1920 was written in black, as was the rest of the page, and then the date of July 8, 1920 was added below it, in blue.

After waiting patiently for a few months, we received a thick, 34-page file from the staff at the “Bad Arolsen” archives in Germany. Fortunately, it contained numerous documents mentioning Jim/Binem, which proved to be very useful to us. The German teacher at our school, Ms. Ruiz, very kindly translated all these documents for us. We thank her warmly for her invaluable help, which included research into the past names of trades and professions.

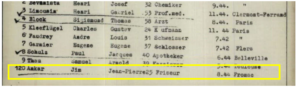

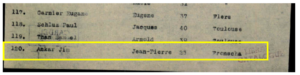

Auschwitz folder 87a, which was compiled after the war, contains an alphabetical list of the prisoners deported on Convoy 77, which left Drancy on July 31, 1944. It includes the name Jun Ankar, who is listed as having been born in Strasbourg on July 8, 1910, and whose last known address is Fronsac in the Haute-Garonne department. These errors as regards his first name and year of birth are similar to those found in other documents:

Alphabetical list of the prisoners deported on Convoy 77, compiled after the war (Auschwitz folder 87a)

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

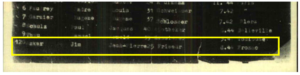

According to the list of French survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp (folder 87a), Jim Ankar was 25 years old when he was liberated from the camp and is listed as a hairdresser. His last known address was Fronsac (the name of the village is misspelled “Fromac”) and his father’s name was Jean-Pierre:

List of French survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp (folder 87a)

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

These same details are listed in the barely legible list of prisoners in the camp:

List of prisoners in Auschwitz (folder 87a)

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

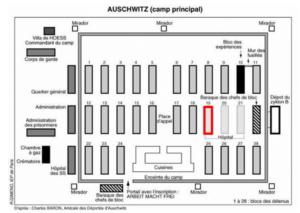

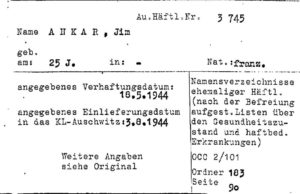

The register of names of prisoners in block 19 at Auschwitz concentration camp also includes Jim Ankar, prisoner number B-3745, 25 years old, French, from Fronsac in the Haute-Garonne department, arrest date 18 May, 1944, date of arrival at Auschwitz 3 August, 1944[20].

Register of names of former prisoners in Auschwitz Block 19 (list compiled after the war)

The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

Jim was reported to have been in good health and had not been abused. For the first time, his occupation was listed as ‘nurse’. After some research, we discovered that block 19, which was part of the Auschwitz “hospital”, was used for patients who were kept in isolation and for those used for medical experiments. This may explain the reference to “nurse”, even though Jim had no medical skills as far as we know. Why would he have been assigned to this block? Did he lie about his skills in order to escape abuse, or even death, and be treated a little less badly than the other deportees? Did a fellow prisoner help him to get in? Did he have better food rations there? In any event, this could explain the fact that he only lost 7 or 8 pounds during his time in detention.

Plan of Auschwitz showing the location of block 19

Source: according to Charles Baron from the Amicale des Déportés d’Auschwitz (Association of Auschwitz Deportees)

The list of survivors who were cared for in the Polish Red Cross hospital in Auschwitz after the camp was liberated also includes the same information. This means that he was repatriated under his assumed name of “Jim Ankar”:

List of survivors who were cared for in the Polish Red Cross hospital in Auschwitz after the camp was liberated

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

After the liberation, the Polish Red Cross hospital was managed by Joseph Bellert, who wrote a report about it[21].

Here are the key events from Joseph Bellert’s report, in chronological order:

- 21 January, 1945: the Germans evacuated the last convoy of prisoners from Auschwitz CC, leaving behind the invalids who were unable to walk.

- 27 January 1945: The Red Army liberated the camp

- 5 February 1945: A team of doctors, headed by J. Bellert, arrived at the camp and set up a hospital. They found: about 2,200 sick people in Birkenau 1, about 800 sick people in Auschwitz, about 800 sick people in Monowitz and 300 dead people. All the sick people were gathered together in one hospital in Auschwitz.

- 17-18 March 1945: 56 children from the Auschwitz camp were moved to Katowice (Kattowitz) under the guardianship of the “Caritas” organization. About 100 sick people died during this period.

- May 1945: Ten doctors who were ex-prisoners in Auschwitz worked together with the Polish Red Cross team, including Dr Mostewej Arkady, a Belgian citizen. The seriously ill ex-prisoners were gradually transferred to the St. Lazarus hospital and to health facilities in Krakow. At this point, the hospital was officially named “Polish Red Cross Hospital in the Auschwitz camp”. In addition, a Belgian mission visited the camp, but the date is not mentioned in the report.

- 1 August 1945: Dr. J. Bellert left Auschwitz; Dr. Jan Jodlevski became the hospital manager.

- 1 October 1945: The hospital was closed down. The recovering patients left the camp and those still sick were moved to the St. Lazarus hospital and to health facilities in Krakow[22].

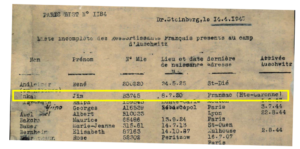

Dr Steinberg compiled an (incomplete) list of French nationals who survived the Auschwitz camp, made on April 14, 1945:

The (incomplete) list of French nationals who survived the Auschwitz camp, made on April 14, 1945

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

This confirms Jim’s Auschwitz prisoner number as B-3745, his (false) date of birth as July 8, 1920 and his most recent address as the village of Fransac (misspelled yet again) in the Haute-Garonne department.

The list of deportees who arrived in Marseille on April 29, 1945 also includes Jim Ankar, born on July 8, 1920[23]:

The list of deportees who arrived in Marseille on April 29, 1945

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

From this list, made by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s list of French nationals on May 24, 1945 we discovered that Jim arrived in Marseille from the Ukrainian port of Odessa. Founded in November 1914, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, or JDC, was an organization that provided assistance to Jewish refugees and the diaspora[24]:

List of French nationals drawn up by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee on May 24, 1945

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

However, we do not know how or when Jim was transferred from Auschwitz to Odessa.

Map showing the Ukranian port of Odessa, on the Black Sea

The alphabetical register of Polish Jews issued in Warsaw in December 1945 confirms, if further proof were needed, that Jim Ankar was indeed imprisoned in Auschwitz and that he was a Jew:

The alphabetical register of Polish Jews issued in Warsaw in December 1945

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

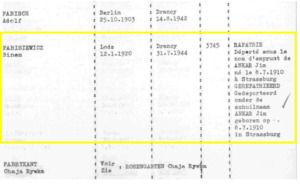

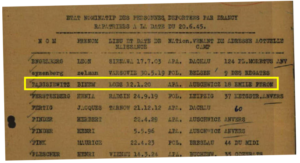

The Victims of War department, under the auspices of the Ministry of Public Health and Family, drew up an alphabetical list of persons domiciled in Belgium on May 10, 1940. The Nazi occupiers arrested them in France because they were Jewish. They were then deported from France to the extermination camps in Upper Silesia on convoys that left from the Drancy internment camp and from camps in Compiègne, Pithiviers, Beaune La Rolande and Angers between June 8, 1942 and August 17, 1944:

Alphabetical list of people domiciled in Belgium on May 10, 1940 who were then arrested in France because they were Jewish and deported to extermination camps in Upper Silesia on convoys that left from the Drancy internment camp and camps in Compiègne, Pithiviers, Beaune La Rolande and Angers between June 8, 1942 and August 17, 1944

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

The information below, from the Shoah Memorial in Paris, confirms our deportee’s double identity: Jim Ankar, born on July 8, 1910 in Strasbourg, was simply a fake identity. He was really Binem Fabisiewicz, born in Lodz, Poland, on January 12, 1920, and was deported from Drancy on July 31, 1944 as prisoner number 3745.

Binem Fabisiewicz’s registration card, issued on March 20, 1946 by the Belgian Commissariat au Rapatriement (Office of the Commissioner for Repatriation) lists him as married, Polish, born on January 12, 1920 in Lodz, Jewish, with a father named David and a mother named Rachelle. His destination address corresponds to that of his parents, 179 rue Emile Fairon (incorrect spelling yet again) in Belgium, where he was living on January 1, 1938. He is listed as a leather worker, who spoke French, Polish and German. A handwritten note has been added to the document stating that Binem/Jim left in June 1941 for France, was deported and returned home from Germany on April 29, 1945:

The front of Binem Fabisiewicz’s registration card issued on March 20, 1946 by the Belgian Commissariat for Repatriation

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

What is touching about this document is Binem’s handwritten signature, which is proof that he survived after having been deported.

It does not include any medical observations, which would seem to confirm the fact that he was in reasonably good health on his return.

The back of Binem Fabisiewicz’s registration card issued on March 20, 1946 by the Belgian Office of the Commissioner for Repatriation

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

The name of Binem Fabisiewitz, born in Lodz on January 12, 1920, a stateless person who had come back from the Auschwitz camp and whose address was 18 Emile Féron, also appears on the list of people deported from Drancy who were repatriated on June 20, 1945, who then returned to Belgium. This list was drawn up in order to identify and offer assistance to Jewish war victims:

List of people deported from Drancy, repatriated on June 20, 1945, who then returned to Belgium

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

A decree dated December 31, 1945 listed the Jews who had been liberated from the German concentration camps and had arrived back in Belgium. The first part of the list gives the names of those who had been living in Belgium before May 10, 1940 and had returned by December 31, 1945:

List of Jews who had been liberated from concentration camps in Germany and had arrived back in Belgium, according to the decree dated December 31, 1945

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

Binem Fabisiewitz, born in Lodz on January 12, 1920, is again listed as a stateless person. The letter “P” in the last column denotes deported prisoners who had not passed through a Jewish assembly center.

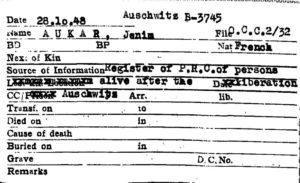

One record, in the register of persons alive after the Liberation, dated October 28, 1948, gives details of a certain Aukar Jenim (a double typing error?), a French national who had been a prisoner in Auschwitz. His registration number, B-3745, leads us to believe that this was in fact Binem:

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

In the register of names of former prisoners[25], on page 90 in folder 183 of the Bad Arolsen archives, a card lists Jim Ankar, 25 years old, a French citizen, as having been arrested on May 18, 1944. The date on which he was known to have arrived at the Auschwitz camp is given as August 3, 1944 and his registration number is listed as 3745.

Source: The German “Bad Arolsen” archives (International Centre on Nazi Persecution)

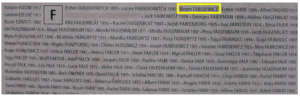

Via a Polish contact of the Convoy 77 association, we then asked the archives service in Lodz to confirm Binem’s identity. After having waited patiently for four months, we received some invaluable documents and the following message[26] :

“I’ve found some interesting papers related to Binem Fabisiewicz from Łódź/Brzeziny. It wasn’t easy, because he was attached to the registry in Brzeziny, not in Łódź. His grandfather died in the Łódź Ghetto (APŁ, PSŻ scan).”

Firstly, we discovered that Binem was officially registered in Brzeziny (his father’s place of birth) rather than in Lodz (his own place of birth) and that his grandfather, whose first name was Lajse, died in the ghetto in Lodz.

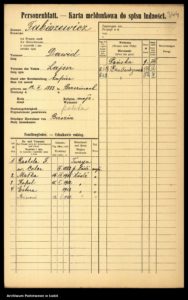

Personal Record – Registration card for the census

Source: Polish State archives in Lodz

This registration card, in the name of Dawid, Binem’s father, confirms his ancestry. Dawid was born on February 12, 1883 in Brzerziny. He was a Polish citizen, of Jewish faith and his father’s name was Lajser. Dawid worked as a merchant and lived in Brzeziny. The family members are listed as follows:

- Rachela, his wife, born in September 1883 in Tuszyn (maiden name: Coler)

- Malka, their daughter, born on September 16, 1905 in Lodz

- Kopel, their son, born on January 15, 1912 in Lodz

- Estera, their daughter, born in 1913 in Lodz

- And lastly Binem, born on January 12, 1920 in Lodz.

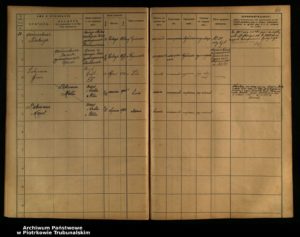

A page from the register in Cyrillic script showing Binem’s civil status (parents, date and place of birth, brother and sisters and that he was single at the time)

Source: Polish State Archives in Piotrkow Trubunalski

A summary of the Fabiszewicz family tree can be found on the genealogical website jri-poland.org :

A record taken from the website https://jri-poland.org/

To further our investigation, we had the opportunity to hold a video-conference with Alexandre Doulut, a French historian who specializes in the deportation of Jews from France[27] and who has also worked with the Convoy 77 association:

The historians Alexandre Doulut and Sabine Labeau

Source: https ://media.sudouest.fr/10042196/1200x-1/so-57ece1a466a4bd1954190e4b-ph0.jpg

Having learned about our project, Alexandre Doulut sent us an email saying: “Your work is very impressive, frankly. Bravo for getting the documents from the Arolsen and the Belgian Archives. This enables us to fill a gap in his biography. If we are to believe the Arolsen record, he returned to Belgium in 1946.”»

Our conversation with Alexandre Doulut gave us a little more confidence in our work and, above all, allowed us to accept the fact that we would probably never find out anything more about the life of Jim Ankar/Binem Fabisiewicz, who appears to him to be an “enigmatic figure”.

Unfortunately, due to time constraints and research difficulties, we have not been able to find Jim’s date and place of death, nor which youth workcamp he passed through, nor his place of incarceration in Toulouse, nor indeed any descendants (might he have had a child or two?). We still wonder about the reasons for his double identity. Did he change it simply to hide the fact that he was Jewish? Did he adopt someone else’s identity or did he just make it up?

The account given in the Saint-Gaudens police reports is deeply disturbing[28]: why would he lie? did he have any reason to lie? If he was Jewish, then clearly he did…[29]

The fact that we were unable to find out anything about him after the war suggests that he wanted to be forgotten. Alexandre Doulut confirmed that for some deportees this was not unusual, as they wanted to wipe the slate clean after that traumatic period in order to start anew in their “after” lives.

We found Binem’s name listed on the Yad Vashem website:

The site confirms some of the information that we found[30]. Some of it comes from the List of people deported from France (1942-1944), published in 1978 in Paris in Le Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France (Memorial of the Deportation of the Jews of France) by Béate and Serge Klarsfeld.

This site also lists a Kopel Fabisiewicz who was in Brussels, Belgium during the war and who also survived the Holocaust (but was not on Convoy 77):

Could he have been Binem’s brother?! This could be the beginning of a whole new investigation!

Conclusion

During his testimony at the Barbie trial, Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1986, stated:

“The killer kills twice. First, by killing, and then by trying to wipe out the traces.”

Jim will stay with us for a long time, so much has this project affected us and inspired us to grow. We found it very moving to follow in the footsteps of this man. Contributing to the “big picture” by means of a “small” individual story has been really exciting. We humbly hope that our work will bring Jim back from the silence and anonymity in which the Nazis wanted to plunge him for eternity, so that he will now have his place in our collective memory.

“Jim” led us on a great collective adventure, even though there remain many grey areas: he never wanted to reveal himself to us completely. His secrets made us question everything, and we came up with the craziest and most outlandish hypotheses. His secrets are a part of him, however, and we have accepted them entirely, even though we regret not having been able to identity his child/children, or more about his wife, or where he was interned in Toulouse.

We now understand better why, unlike the other deportees, Binem Fabisiewicz’s name appears on the Wall of Names among the names beginning with the letter F and with no date of birth:

To pay tribute to him and to honour his memory, we suggest that his real birth year, 1920, be added to the Wall[31].

Chronology of the life of Jim Ankar/Binem Fabisiewicz

- January 12, 1920: Binem Fabisiewicz was born in Lodz, Poland. He was the son of David, a merchant, born on February 12, 1883 in Brzeziny and Rachela, born in September 1883 in Tuszyn. He was the grandson of Lejzir Mindel Fabisiewicz, born in Zyrankow, and Dczabozaporski Rapir, born in Brzeziny, all of whom were Jewish.

- 1931: He arrived in Belgium from Lodz. He was a leatherworker and a Jew. He was married to Hélène Herskovic, born on July 8, 1922 in Birchow [32].

- January 1, 1938: he was living in Belgium, at 179 rue Emile Féron in Saint-Gilles, Brussels.

- At the beginning of the war: there is evidence that he was in Belgium on May 10, 1940. He stated that he was living at 28, rue Emile Féron in Saint-Gilles, Brussels, with Juliette Corwarie, born on January 5, 1923 in Budapest, Hungary, who was the daughter of Michel Corwarie and Elisabeth Cowach.

- 1940: the Fabisiewez family took refuge in Fronsac[33].

- October 1940: Binem arrived in France. He was mobilized and spent some time in a youth work camp (as yet unidentified).

- Sometime in January 1941: he stated that he had returned to Belgium where he had married a young Hungarian woman. He then had a French identity card issued to him by the Fronsac town hall.

- February 22, 1941: he said he had married Juliette Corwarie, who then became Juliette Ankar, in Saint-Gilles, Brussels. However, there is no trace of a marriage record in either of these names at the civil registry office in Saint-Gilles.

- As of February 25, 1941: they lived at 179 rue Emile Féron in Saint-Gilles, which was Binem’s parents’ address.

- They then moved to 62 rue du Collecteur in Anderlecht.

- As of May 3, 1941: they went back to live at 28 de la rue Emile Féron, in Saint-Gilles (Brussels).

- June 1941: he left for France.

- October 1942: he came back to France, leaving his wife in Belgium and his identity card with some friends in Lille. He stayed for a while with the Fabisiewez family in Sirada (a family that took refuge in Fronsac in 1940 since a number of family members had been interned in camps). This family would seem to have been “of Jewish race” according to the name of the head of the family, David Fabisiewez, a storekeeper and grocer at 179 Rue Emile Féron in Brussels, who was born in 1883 in Brzeziny. In fact, Jim moved in with his parents! He then set up home in Saléchan in the Haute-Pyrénées department). He had the identity card that had been issued by the mayor of Fronsac exchanged for a card issued in Saléchan. He said that he had handed back the identity card that had been issued in Fronsac to the town hall there.

- Early November 1942: he returned to Belgium in order to bring his wife back to France. He travelled through France using the card issued by the Saléchan town hall and through Belgium using his Belgian identity card, which he collected from his friends in Lille.

- November 24, 1942: He returned to Saléchan but was unable to find a place to live, so he and his wife set up home in Fronsac.

- November 27, 1942: Juliette Ankar was issued a French identity card by the mayor of Fronsac.

- January 20, 1943: Jim and Juliette were interviewed by the police in Saint-Gaudens in Haute-Garonne department of France. They were still living in Fronsac at the time. Juliette was confined to bed because she was pregnant. Although she was not legally resident in France, the police did not arrest her.

- May 18, 1944: Jim was arrested by the Gestapo during a round-up at the Saint-Cyprien railroad station in Toulouse and then interned somewhere in Toulouse (location not identified as yet).

- May 22, 1944: He was transferred from Toulouse to Drancy camp, with the registration number 22971. He was searched on arrival and the money he had on him, 3630 francs, was confiscated.

- July 31, 1944: he was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz, in Poland, on Convoy 77.

- August 3, 1944 [34]: he arrived at the Auschwitz camp, where he was issued the number B-3745. He was assigned to block 19 in the camp, which was used for sick people in the isolation ward and for medical experiments on prisoners. His camp discharge form states that he was a “nurse” there.

- January 27, 1945: The Auschwitz camp was liberated by the Red Army.

- He was taken to the Polish Red Cross hospital in the Auschwitz camp. He was then repatriated under his assumed name of Jim Ankar.

- February 21, 1945: the local department of the Ministry of Prisoners of War, Deportees and Refugees in Haute-Garonne issued a certificate stating that Jim had been deported from Toulouse to Drancy, but he never went to collect it. This information was sent to Mrs. Ankar, at 41 boulevard des Récollets in Toulouse.

- According to the (undated) report drawn up by the Regional Delegation of the Ministry of Prisoners of War, Deportees and Refugees (and stamped by the Comité des Œuvres Sociales des Organisations de la Résistance (Commitee for Social Welfare of the Resistance Organisations), Jim had two children.

- April 29, 1945: he was repatriated from Auschwitz to Marseille via the Ukrainian port of Odessa. He survived the deportation: a such, he was among the 214 Convoy 77 survivors.

- He returned to Fronsac after he was liberated.

- June 20, 1945: His name appears on the list drawn up to provide help to Jewish war victims. He is listed as a stateless person, having returned to Belgium to live at 18[35] rue Emile Féron in Saint-Gilles.

- December 31, 1945: on the list of Jews liberated from the German concentration camps, he is listed as having resided in Belgium before May 10, 1940 and having returned by December 31, 1945.

- March 20, 1946: the Belgian Commissariat for Repatriation issued a registration card signed by Binem Fabisiewicz.

- March 19, 1948: a record from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War signed by the Head of the Bureau of Files and Civil Status of Deportees confirms that Jim or Jun Ankar was classified as a political deportee.

- October 28, 1948: he is listed in the register of people who were alive after the Liberation.

[1] However, we found another birth date for his mother: September 1883.

[2] Source: Wikipédia.

[3] This is the file from the regional delegation of the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees (PDR), which would later become the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs.

[4] Not the 8th, which appears to be an error.

[5] According to the historian Sandrine Labeau, this document “looks very much like a request for information from his wife.”

[6] Source: https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr, pages 3 and 4.

[7] Source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chantiers_de_la_jeunesse_fran%C3%A7aise

[8] Source: https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/rechercheconsultation/consultation/ir/pdfIR.action?irId=FRAN_IR_000881 (pages 4 and 5).

[9] The historian Sandrine Labeau explained to us that the decree dated May 11, 1945, initially dealt with the repatriated persons’ situation as a matter of urgency and laid the foundations for a special status for deportees, although no distinction was made between members of the Resistance and other people (the term “racial deportee” was used at that time). It was not until 1948 that the deportation was officially recognised, along with the various reasons for and purposes of the deportation, thus distinguishing between deported Resistance fighters and those deported for “political” reasons:

- A law dated August 6, 1948 introduced the status of deported and interned members of the Resistance (DIR). The DIR status applied to people deported to concentration camps, interned and/or tortured, as a result of their participation in the Resistance.

- A law dated September 9, 1948 introduced the status of political deportee and internee (DIP). The DIP status was mainly aimed at Jewish deportees and internees, but it also covered people arrested by both the Germans and the French on account of their political or philosophical views.

The families of the victims, or the victims themselves if they survived, were then able to put together an application file for the title of political deportee (DP) or Resistance fighter (DR). For the survivors, the applications are kept in a separate collection at the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service. Neither Sandrine Labeau nor Alexandre Doulut found an application in the name of Jim Ankar or Binem Fabisiewicz during their research for the Convoy 77 association. The original medical record card is usually included in this file. In this case, since Binem Fabisiewicz clearly did not apply for the status of political deportee, the departmental branch of the Ministry nevertheless compiled a file with the information it had on him, in particular a copy of the medical form drawn up upon his return to France. Similarly, on a national level, the Ministry compiled a dossier, now called the “old file”, which we will refer to later on.

[10] This bears the number 16.

[11] The box bears the reference 2054 W 1502.

[12] We have adhered to the spelling in the original document.

[13] This bears the number 17.

[14] File kept in an area of the National Archives at the Shoah Memorial.

[15] Card sent by the National Archives service

[16] Compiled after the war by the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees, this file is kept at the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, as are the applications for the status of Political Deportee or Deported Resistance fighter as well as the records in the “old file”.

[17] As is also confirmed by the search log of the Drancy camp provided by the Shoah Memorial.

[18] Once again, no details are given as to the place of internment in Toulouse.

[19] The International Documentation Center on Nazi Persecution.

[20] Although a medical card from the file of the Toulouse Delegation found in the Departmental Archives mentions August 4, 1944 as the date of arrival in Auschwitz.

[21] His report is entitled: “The work of Polish doctors and nurses at the Polish Red Cross Camp Hospital in Oświęcim after the liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp”

[22] Dr. Bellert’s reports were reportedly handed over by the Polish Red Cross of the Krakow region to the central Red Cross archives in Warsaw.

[23] Yet another error in the date of birth!

[24] Source: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/fr/article/american-jewish-joint-distribution-committee-and-refugee-aid

[25] Lists drawn up after the Liberation relating to the deportees’ state of health, conditions of detention and illnesses.

[26] Unfortunately, we were unable to make use of them all, as one of them is a register written in Cyrillic that we did not have time to have translated.

[27] His thesis, entitled La déportation des Juifs de France, changement d’échelle (The deportation of Jews from France, changing the scale), will be published in September 2023. He has also co-written, with Sandrine Labeau and Serge Klarsfeld, two books on Jewish survivors from France in 1945. Les rescapés juifs d’Auschwitz témoignent (Jewish survivors of Auschwitz give their testimony) (2015) and Mémorial des 3943 rescapés juifs de France (Memorial to the 3943 Jewish survivors from France) (2018) in which they published the complete testimony of Dr. Samuel Steinberg taken by the Service de Recherche des Criminels de Guerre (War Criminals Research Service) after he returned in July 1945.

[28] In particular, the fact that he says he was taken in by the Fabisiewez family from the age of 5 to 20.

[29] The historian Sandrine Labeau explained to us by email: “As for Binem Fabisiewicz’s possible Resistance activity, it seems unlikely, as the letters “DP” (Political Deportee) on the front cover of the file issued by the Regional Delegation of the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees, as well as on his medical record and in the National File tend to prove. It is also noted in the document [from the AD31], which looks very much like a request for information from his wife, that he was caught during a round-up: “reason for arrest? (in a round-up)”. Finally, if he had been caught in the context of his resistance activity, he would have first passed through Fresnes prison, as was the case for another Convoy 77 deportee, before being sent to Drancy, from which only convoys of Jews departed. In my opinion, he took on a new identity simply to escape the persecution that was being suffered by the Jews.”

[30] https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=en&itemId=3172527&ind=1

[31] The students chose a range of formats for their final contribution to the project. While most students wrote biographies on their own or in groups, two students chose to put themselves in Jim’s shoes in order to “have him speak for himself ” in a very moving autobiography addressed to his wife and child. Three groups of students also chose to portray Jim’s journey by producing three escape games, each with a very different atmosphere. You will find the links to these games in the list below.

23 out of the 38 students in the working group decided to present this subject as part of their oral examination for the French National Diploma of Secondary Education. They fully embraced the investigative approach advocated by the Convoy 77 project and approached the story of the deportee with sensitivity and humility. Some of them drew parallels with their own family history (notably with their grandparents who were members of the Resistance) as well as with some reading that they did during this year’s French class.

[32] The name of the locality is not very legible; unfortunately, we were unable to identify it with any certainty. It may be Brochow, which is a Polish village about 35 miles (57 km) north of Łódź.

[33] At least two of Binem’s relatives, and perhaps his brothers and sisters too?

[34] His medical card, on the other hand, found in the files of the Main Delegation of Toulouse in the Departmental Archives in Toulouse lists August 4 as the date of his arrival in Germany (which should be understood as “in the Reich”, which Nazi-occupied Poland was included at that time)

[35] Or more accurately at number 28, which was one of his previous addresses and where he was living on May 3, 1941, as stated in the document from the “Register of Jews” (KD_0008), kindly transmitted by the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels.

Français

Français Polski

Polski