André WOLFF-VANDOR

We, Johann, Malo, Yannis, Antoine and Titouan, wrote this biography in April 2025, with contributions from Ambre-Ayan, Rayan, Dany, Coline and Anna and with the guidance of our History and Geography teacher, Mr. Stéphane Autret.

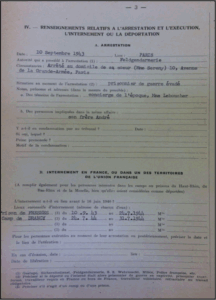

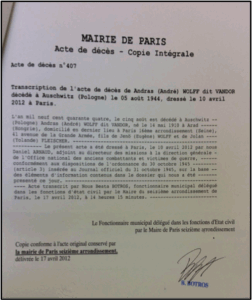

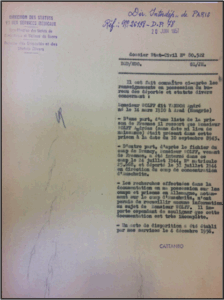

The image on the left is a page relating to André Wolff-Vandor’s deportation certificate. Source: file on Andre Wolff-Vandor, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

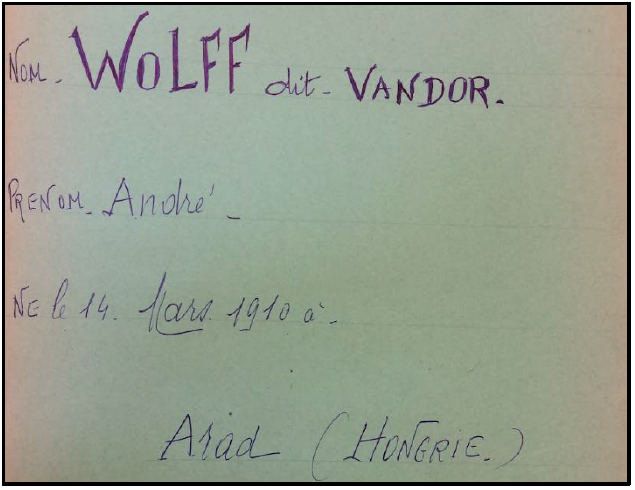

Andras (André) Wolff later known as Wolff-Vandor, was born on March 14, 1910 in Arad, in Transylvania, which at that time was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire[1].

A Jewish family of merchants

Andras/André’s parents were Jenö (Eugène) Wolff, a wine merchant who was born on January 7, 1878 in Glogovăt, and Jolan (Yolande) Fleischer, who was born on October 13, 1882 in Arad.

Jenö’s parents were Alexandru Wolff and Paulina Stein, while Jolan was the daughter of Vilhelm Fleischer and Pepi Doman. They were all Jewish.

The Jewish community in Arad was well-established and prosperous. As of 1867, anti-Jewish discrimination had been outlawed by the local Chamber of Deputies. After the First World War, however, the situation became increasingly hostile. In the 1920s and 1930s, Fascist clubs began to spring up, especially in universities. The police began to ignore anti-Semitic attacks.

Andras was the youngest of three siblings. He had a brother Gyula (also known as Jules and Jules-Georges), who was born on March 31, 1905 in Arad and a sister, Elisabeth, born on April 4, 1908, also in Arad.

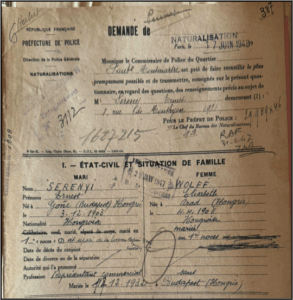

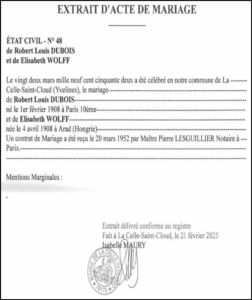

Elisabeth married for the first time in 1932. Her husband was Ernest Serenyi, who was born on December 3, 1903 in Budapest, Hungary. He joined the R.M.V.E. (Régiment de Marche des Volontaires Étrangers or Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers) in Paris at the start of the war. Twenty years later, she got married again, this time to Robert Louis Dubois, an electrical engineer who was born on February 1, 1907 in the 10th district of Paris.

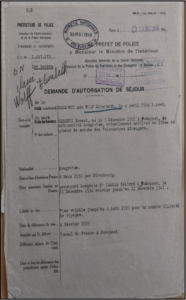

Pages from Elisabeth Wolff’s residence permit application. © French National Archives, Moscow collection, Dossier n°19940485/6.

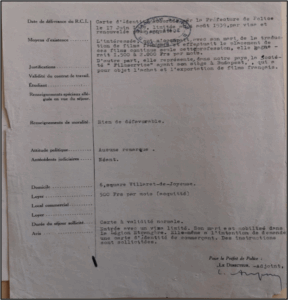

Elisabeth, who worked for a movie company called Filmservice, based in Budapest, Hungary, applied for a residency permit for France, noting that her husband, Ernest Senyi, had volunteered to fight in the French Foreign Legion.

A page from Elisabeth Wolff’s application to be naturalized as a French citizen, after the war, in 1946. © French National Archives, Moscow collection, Dossier n°19940485/6.

Elisabeth Wolff and Robert Louis Dubois’ marriage certificate

© La Celle-Saint-Cloud municipal archives

Unfortunately, our search for any possible descendants and our request to consult the archives in Arad were unsuccessful, so we were unable to find more details about the brothers’ genealogy, nor could we find a photograph of them.

The brothers’ arrival in France

Driven from their homeland, probably as a result of the Nationalists’ anti-Semitic persecution and financial problems caused by the Great Depression of 1929, the Wolff brothers[2] migrated to France in 1939.

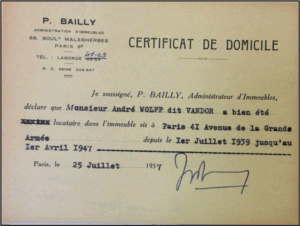

André Wolff-Vandor’s residency certificate, covering the period July 1, 1939 to April 1, 1947 © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

View of the Avenue de la Grande Armée from the Arc de Triomphe, Paris 1931,

© French National Library, Gallica

Their sister Elisabeth and her husband arrived in France before them, on March 6, 1939, via Strasbourg, on a provisional visa; she was working in the film industry for the Budapest-based company Filmservice. She worked as a translator and sourced French films for export to Hungary. In April 1940, she applied for a work visa.

In 1940, while her husband was away serving in the Foreign Legion, she lived at 6, Square Villaret-de-Joyeuse, in the 17th district of Paris, in a rented apartment that cost 500 francs a month. The siblings’ mother, Yolande, was also living in Paris.

André was not only a draughtsman, like his brother, but he was also an artist and painter. We were unable to find out anything else about his pre-war life.

It is unclear exactly when the family moved to 41, avenue de la Grande-Armée, near the Place de l’Étoile (now Place Charles-de-Gaulle). It appears to have been a fine building, which would suggest that the family was fairly well off. However, a police investigation revealed that in 1940, Elisabeth “earned between 1,500 and 2,000 francs a month”[3], and that she was living elsewhere at the time.

We have no information about André’s physical appearance.

Involvement in the Resistance

Unlike his brother-in-law, Ernest Serényi; and his brother Jules-Georges, André does not appear to have joined the R.M.V.E. (Régiment de Marche des Volontaires Étrangers or Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers).

When Jules-Georges, an escaped prisoner, returned to Paris, the two brothers decided to put their artistic talents to good use, by working for the Resistance. It appears to have been around this time that they began using the surname “Vandor” in addition to their birth name of Wolff. In Hungarian, “Vándor” means “wanderer”, so perhaps they chose this name to reflect their Hungarian-Jewish roots. We should also note there that Wolff aka Vandor is the name used on their missing persons and death certificates.

It was for this reason, coupled with Jules-Georges’ status as an “escaped prisoner of war”, that on September 10, 1943, the Feldgendarmerie (German military police) arrested the brothers at their sister’s apartment at 41 avenue de la Grande-Armée, in the 16th district of Paris. A record from the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War states that the concierge, a Mrs. Leboucher, witnessed their arrest[4].

These records give the reasons for which the Wolff-Vandor brothers were arrested on September 10, 1943. André Wolff-Vandor © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024, Jules Wolff-Vandor, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-069

Another record, containing information provided by the family, says “Arrested at his sister, Mrs. Sereny‘s home [by the Feldgendarmerie], at ’10’, avenue de la Grande-Armée, Paris” [with] his brother André“; “Accused of having made up false papers (as draftsmen) for Resistance members; [they] then apparently discovered his Jewish origins.”

This proves that the Wolff-Vandor brothers were involved in the Resistance.

We do not know exactly what led to their arrest that day. Were they part of a network whose members were under surveillance? It is not possible to produce forged identity papers without being part of a group, but we know nothing about their undercover connections.

As far as we are aware, none of the Resistance networks named André Wolff-Vandor as members.

Deported and murdered because he was Jewish

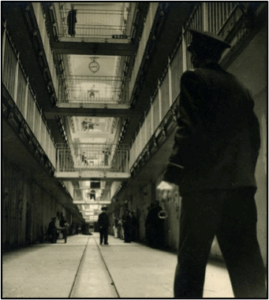

It was only after they were arrested that the Germans discovered the brothers’ Jewish roots. They were sent to Fresnes prison, in the Val-de-Marne department of France, that same day. During the Occupation, “Fresnes prison was the largest repression center for Resistance fighters”[5].

Detained as political prisoners, André et Jules, like many other Resistance members, were forced to live in inhumane conditions: the place was overcrowded, tortured was commonplace, and so on. They remained in Fresnes until July 24, 1944, when, listed as Jewish prisoners (rather than Resistance members), they were sent to Drancy internment camp, north of Paris, where the Germans were getting ready to send one last transport to Auschwitz[6]. Forty four prisoners, some men, some women, were taken from their cells in Fresnes to be deported on Convoy 77.

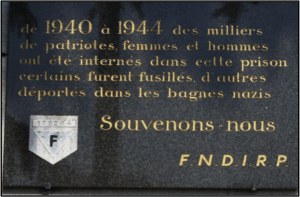

Photo 1: The main corridor in Fresnes (1945-46) © Criminocorpus,

Photo 2: Commemorative plaque at Fresnes prison erected by the Fédération Nationale des Déportés et Internés Résistants et Patriotes (National Federation of Deported and Interned Resistance Fighters and Patriots) © French Resistance Museum website

In July 1944, SS Officer Hauptsturmführer Aloïs Brunner was in charge of Drancy camp. Following the Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, Brunner set about deporting as many Jews as possible before time ran out[7].

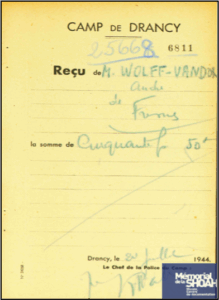

When André arrived in Drancy on July 24, he was searched and had 50 francs confiscated from him, as shown on the search log slip below. He was then assigned the registration number 25,668 and sent, together with his brother, to a 5th floor room on staircase 18. They were categorized as “deportable immediately”.

André’s search receipt from Drancy camp

© Shoah Memorial, Paris

Prisoners in the camp were forbidden to correspond with the outside world, and parcels containing food or personal items, which had been allowed in before Brunner took over, were also banned. Although conditions were a little less grim than in 1943, the camp was nevertheless ruled by terror and, as a result of the France-wide roundups that Brunner initiated on April 14, 1944, it soon began to fill to capacity. There is no evidence to suggest that André was in contact with his mother or sister.

Prisoners waiting for the soup at Drancy (1942),

© Shoah Memorial/French National Library Collection

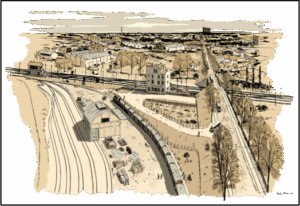

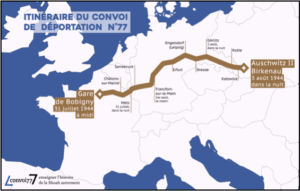

At dawn, on July 31, 1944, André and Jules, together with everyone else who was to be sent to Auschwitz, were loaded into buses from Paris and taken to the nearby Bobigny station, where a train was waiting for them. The train, which belonged to the French National Railway Company, the S.N.C.F. was made up of 30 cattle cars. 1306 people, including 324 children were forcibly loaded onto the train. Armed soldiers acted as escort. The single men, such as André and Jules, were kept together in separate, well-guarded cars, in case they should try to escape. Families travelled together in other cars, as did women and children.

The convoy set off around midday, passed through the French cities of Châlons-Sur-Marne and Metz, and by the morning of August 1, it had reached Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany. It arrived in Poland after passing through Görlitz, in Germany, during the night of August 2, and finally reached Auschwitz II-Birkenau in Poland in the early hours of Thursday, August 3, 1944[8].

The traveling conditions on the train were absolutely appalling. There was just straw strewn on the floor, very little drinking water and a bucket for a toilet[9].

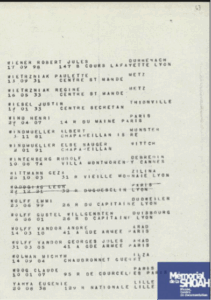

The original Convoy 77 deportation list, dated July 31, 1944 including the names of the two Wolff-Vandor brothers. @Mémorial de la Shoah

Image 1: Sketch of Bobigny station, as it was in 1943,

© Etienne Martin, LM Communiquer

Image 2: The route taken by Convoy 77 Source: Convoy 77 nonprofit association

André was most likely murdered in the gas chambers soon after the train arrived, following the selection that took place immediately on the Banhrampe in Birkenau. Although he was later officially declared to have died on August 5, he was almost certainly killed on August 3, together with his brother. However, it’s not inconceivable that he was selected to go into the camp to carry out forced labor[10].

Andras (André) Wolff-Vandor’s death certificate, issued by Paris City Hall. © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen n°21-P-551-024

Another possible scenario is that the brothers were part of a group of men who had been planning to escape ever since they left Drancy. They tried to escape along the way, but failed, and after they were captured, the 60 men from the “escapees car” were gassed immediately when the convoy arrived in Auschwitz.

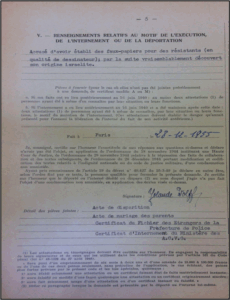

This summary from the “Department of Status and Medical Services for deportees” outlines the main ways in which André Wolff-Vandor was persecuted. © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

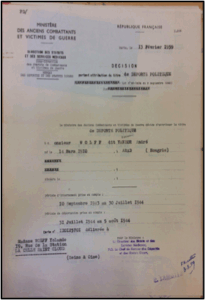

After the war, their sister, Elisabeth, and their mother, Jolan/Yolande began the struggle to have André and Jules-Georges officially recognized as “political deportees” (meaning that they were deported because they were Jewish). On February 13, 1959, the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War granted André the status of “political deportee”, based on the period during which he was interned, September 10, 1943 to July 30, 1944, and subsequently deported, from July 31 to August 5, 1944 (which was not the actual but the official date of death, which was convenient for administrative purposes).

Page confirming that the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War had decided to grant Mr. André Wolff-Vandor André the status of political deportee. . © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

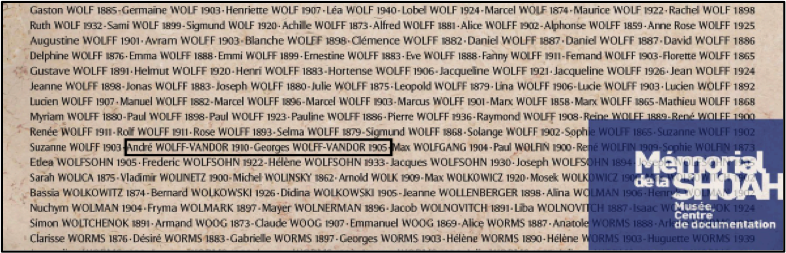

Lastly, Andras, under the French version of his name, André, is listed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

The names of André Wolff-Vandor and his brother Georges are inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

© Shoah Memorial, Paris

In November 2024, during our research for the project, we also recorded a short podcast that tells part of his story, closely linked to that of Convoy 77.

We would like to thank Ms. Claire Podetti, the Convoy 77 project coordinator and Mr. Serge Klarsfeld, the president and founder of the nonprofit organization Fils et Filles de Déportés Juifs de France (Sons and daughters of Jewish deportees from France), as well as Mr. Nicolas Coiffait, a genealogist, for their invaluable help with our research.

Notes & references

[1] From the page relating to his deportation certificate. Arad then belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but became part of Romania after World War I, hence the changes of country names in the records. File on André Wolff-Vandor, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

[2] On their birth certificates, Jules and André’s surname was Wolff. The « known as Vandor », making the surname Wolff-Vandor, was added later, in France. This was the name used on the official documents relating to the brothers’ deaths.

[3] On July 19, 1939, Ernest Serényi, living at 74-76 avenue de La Grande-Armée in the 17th district of Paris, applied for an extension of his residence permit. He declared that he had sufficient means to cover “my own living expenses and those of my wife”. French National Archives, Moscow collection, 19940485/6, file on Elisabeth Serenyi.

[4] Although we asked the Memorial in Caen, the Paris Archives service and the Paris Police Headquarters for more information, we were unable to find any further evidence of the brothers’ involvement in the Resistance.

[5] This is based on information from Mr. Loïc Diamani – a historian at the French National Resistance Museum in Champigny-Sur-Marne – gathered by the journalist Kanumera Creiche for an article in the French newspaper Le Monde, entitled “Le “couloir de la mort“ de la prison de Fresnes fait des histoires” (Fresnes prison’s “death row” is a hot topic”).

[6] We have no further information about their time in Fresnes, despite having asked the Val-de-Marne departmental archives service, as well as checking the registers 2742W 1, 2742W 101, 2742W 109, 2742W 43 and 2Y5 433.

[7] Convoy 77 website, page on the history and the make-up of the convoy, and Wikipedia, ”Convoi n°77 du 31 juillet 1944”.

[8] Convoy 77 website, page on the history and the make-up of the convoy, and Wikipedia, ”Convoi n°77 du 31 juillet 1944”.

[9] Numerous testimonials, including those of Holocaust survivors Denise Holstein and Régine Skorka-Jacubert, recall the appalling travelling conditions : straw on the floor, one bucket of drinking water and one bucket for everyone to use as a toilet. In high summer, the heat and the stench were unbearable. A lot of elderly and sick people did not even survive the journey, but their bodies were left in the cars until the train arrived in Poland.

[10] No further information relating to the brothers’ deportation could be found, and we were unable to examine the Auschwitz archives for ourselves as we had originally intended.

Français

Français Polski

Polski