Anna TUGENDHAT

Two classes, a 10th grade class of German-speaking students and the 11th grade class specializing in History-Geography-Geopolitics-Political Sciences (HGGSP), both from the Marcel Pagnol High School in Marseille, worked together on this project to address the following question: What was it like to be a woman or a child during the extermination campaign in Europe?

The students carried out their investigation using the archived records about six deportees: three Margarete ALT, Anna TUGENDHAT and Henriette COVO, two children, Marcelle KORSSIA and Suzanne KOSLEWICZ and one teenager, Marcel KRAJZELMAN. Each of the classes contributed its own skills: the 10th grade class, with the German-speaking students, translated the archives, carried out part of the historical research and put it into context, while the 11th grade class of HGGSP students acted as their tutors during the investigation and helped them develop a critical approach to the sources and the historical silences in each deportee’s life story

They split into groups according to the investigations to be carried out and then pooled their work. All the projects are related to each other and are organized in similar format. For example, for Anna Tugendhat:

- Investigation: Who was Anna Tugendhat?

- The historical silences in Anna’s story.

- The exhibition in the CDI (Documentation and Information Center, similar to a school library): pooling and presentation of the students’ work on all six projects, school outings, testimonies, visual aids, and sources vs the gaps in the story.

- Students’ observations: Why is it important to work on the history of women, children and teenagers? How does your work help to combat prejudice?

- The investigation translated into Allemand: Die Ermittlung ins Deutsche übersetzt.

I) Investigation: Who was Anna Tugendhat?

1) At the beginning, how many records about Margaret did you have? What did you learn about your deportee from these records? What hypotheses did you put forward?

At the start, we had no records at all about Anna Tugendhat in the Veterans and Victims of War dossier provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit organization www.convoi77.org. We therefore wondered if this person had even really existed.

2) What did you learn by contacting the archives services and/or other people?

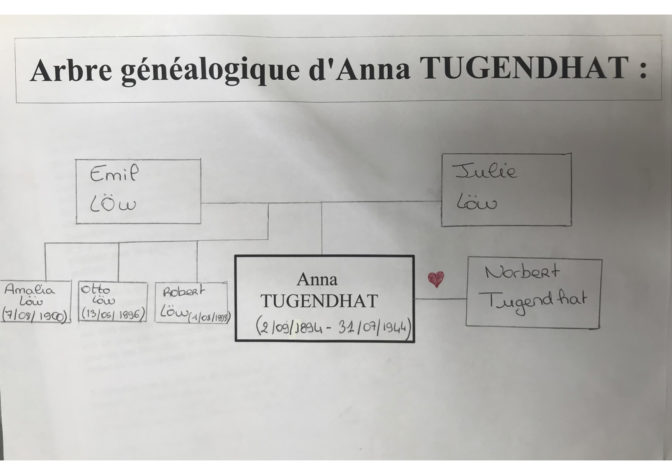

Through the online archives, we discovered that Anna LÖW, or LOEW, was born in Vienna, Austria, on September 2, 1894, as stated on her birth certificate1. Her father was called Emil Löw and her mother Julie Löw, née Arnstein. She had two brothers, Robert Loew, who was born on August 1, 1893, and Otto Loew, born on May 13, 1896, and one sister, Amalia Loew, born on August 7, 1900.

According to Wolfgang Schellenbacher, the wedding probably did not take place in Vienna, but all the children were born there2.

Anna’s birth certificate, ref. Cm. 2152/1894, Jewish Community Archives in Vienna, received in response to an e-mail sent by the students on January 19, 2022 to the DÖW Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance, according to Wolfgang Schellenbacher, and Rz 2152/1894, IKG Vienna Archives in response to an e-mail sent by the students on January 25, 2022, according to Susanne Uslu-Pauer.

In 1938, Austria was annexed by the Nazis during the Anschluss. Anna had to flee Austria and seek refuge in Western Europe. The Italians occupied the principality in November 1942, followed by the Germans in September 1943.

Anna Tugendhat was not arrested in Nice, as it currently says in the database on the Convoy 77 website. In all likelihood, the German police arrested her in Monaco3. She was among a number of Jewish people who were arrested in Monaco during the German occupation in 1944. She was interned in Drancy camp by the “Befehlshader der Sicherheitspolizel” of France as of January 30, 19444.

Map showing various places that Anna spent time in during her life, drawn by Myriam, Razanne and Yousra.

In the Shoah Memorial archives, we discovered that Anna Tugendhat was living at the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo5. When she arrived in Drancy, according to the search book 82, receipt n° 5, she was carrying a bag containing: 1 gold and pearl ring, 2 gold and precious stone medallions, 1 pearl necklace with clasp, 1 necklace clasp, 2 pearls on a broken gold chain, 1 gold and pearl pendant and 1 gold brooch, as well as a cheque book from the Credit Foncier de Monaco bank.

Drancy search log receipt for Anna’s belongings

Shoah Memorial page for Anna Tugendhat

List of people deported from Drancy, including Anna Tugendhat

Henriette COVO

Beside Anna’s name on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris there is a Norbert, who has the same surname as Anna. We suppose that he was a relative of hers6. Also, on the typewritten lists of internees held in Drancy camp from July 16, 1943 to December 12, 1943, detailing each internee’s number, first and last name, age, placement and category for which they were interned, the first names of Anna and Norbert are listed7 although their names are spelled Tugendhadt. Michael Bloche has confirmed that Norbert was her husband8.

We decided to do some research into him.

Norbert Otto Tugendhat was born in Eislingen9 which is now in Germany, on November, 189410. He had three stepsisters: Lieselotte Tugendhat, Annamarie Tugendhat and Annaliese Tugendhat. Their father, Bruno Bronislaw Tugendhat had remarried, to Friederike Fritzi Tugendhat. Norbert was German and Jewish, although to the Third Reich, he was only viewed as a Jew.

Information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 6, 2021 to the records department of the Société des Bains de Mer de Monaco (Monaco Sea Baths Society) according to Charlotte Lubert.

Norbert arrived at the Hotel de Paris, where Anna was living, on September 13, 1943 and left the following day, September 14. He was there again on the night of September 16-17, 1943, from October 1-7, 1943, from October 9-10, 1943, and his last stay was from October 13-15, 194311. According to the Shoah Memorial website, he was arrested and taken to Drancy more than once, on January 14, 1944 and on May 6, 1944. The two search books, numbers 61 and 116, and the receipt numbers, 2490 and 2491, give him the same address: 11 rue d’Odessa in Paris. Like Anna, he was carrying a great deal of jewelry, such as watches, diamonds and money in various currencies: American dollars, French francs and Italian lire.12

Drancy camp search log for Norbert

Shoah Memorial page for Norbert Tugendhat

We put forward two hypotheses: he was well-off, or was involved in trafficking.

Norbert Tugendhat was under surveillance by the Gestapo (Geheime Staatspo-lizei) in Koblenz for an unknown period of time; he was then incarcerated on an unknown date in Drancy camp by the “Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei” in France13.

According to the chronology of deportations in the Memorial Book held in the Federal Archives in Berlin, Germany, 1,300 people were deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. The convoy arrived there on August 3, 1944. We know that Norbert was still being held in the Auschwitz concentration camp on August 15, 1944, as we have a record of an X-ray examination. He was then transferred to the Hailfingen commando in Natzweiler concentration camp on an unspecified date, having come from Auschwitz-Oswiecim. In Natzwieler, Anna Tugendhat husband was assigned prisoner number 40967 on November 16/17, 1944, under the Nazi regime prisoner category “Schutzhaft Jude” (Jewish person held for security reasons)14.

List of deportees from Drancy including Norbert Tugendhat’s name

Shoah Memorial webpage for Norbert Tugendhat

Norbert Tugendhat died on December 2, 1944 at 8 a.m. in the Hailfingen commando of Natzweiler concentration camp, prisoner number 353. The cause of death was myocardial insufficiency. His body was cremated in the Reutlingen crematorium on December 5, 194415.

Anna was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. She was listed as “Juden” (Jewish) by the Nazi regime16. She did not survive.

A memorial stone17, erected in remembrance of these deported people, was unveiled during a ceremony held on Thursday, August 27, 2015, in the Monaco cemetery, attended by His Serene Highness the Prince and the civil and religious leaders of Monaco. The diplomatic representatives of the countries the deported Jews originally came from were also invited, as were some of their descendants and beneficiaries1819.

Article in French in the newspaper Monaco-matin and information received in response to an email sent by the students on December 1, 2021 to the Monaco National Archives, according to Michael Bloche.

3) Were there any lulls during the research? Why? Did you anticipate that you would be able to write such a detailed biography when you began your research?

When we started our research, we didn’t think we would find as many details about Anna and Norbert.

4) In what way does your work contribute to the remembrance of Anna?

Our work was to find some traces of Anna’s life in order to pay tribute to her and to keep the memory of her alive so that she could rest in peace.

During our investigations, we were contacted by Michaël Bloche, who is in charge of preliminary planning at the Monaco National Archives. We took part in a videoconference to share information about Anna on Tuesday, March 22, 2022:

Anna went to the Casino every day, so she must have been wealthy.

Norbert was arrested first, before Anna, in Paris. There were two reasons for this: he was a Jew and he produced false identity papers. He was to be part of a smuggling operation to help stateless people in the South of France.

Anna was arrested because she had a false identity card bearing the name Adèle Montaudon20.

We put forward a hypothesis about the casino, thinking that it may have been a contact point for trafficking and/or resistance activities.

Report from the Public Security agency about Anna’s while using the alias, Adèle Montaudon. French Public Safety Directorate (DSP): 031179 (personal file on Anna Tugendhat) and 111000 (group file in which the personal file is kept).

During our research, we were contacted by the Bundesgymnasium 19 in Vienna, Austria, and the students taking the history option at G19, Gymnasiumstr. 83, 1190 Vienna, under the supervision of Martin Krist. We took part in a videoconference to exchange information about Anna on Tuesday April 5, 2022:

As regards her address, the number 2 actually referred to the floor on which her family’s apartment was located. She worked in a bank. She left Vienna for Hamburg, where she married Norbert. In 1929, she was in Berlin. She spent sixteen years in Germany.

The number of Norbert’s tattoo was B3943.

On the Wall of Names in Vienna, which lists the names of Austrian Jews murdered during the Holocaust, the first name and surname of Anna Tugendhat are included.

Wall of Names at the Memorial for the victims of the Shoah in Vienna, Austria. Photo taken by Martin Krist.

Wall of Names at the Memorial for the victims of the Shoah in Vienna, Austria. Photo taken by Martin Krist

Anna’s former home in Vienna., Photo taken by Martin KRIST.

On May 10, 2022, Martin Krist sent us an email about the rest of the research done with his class and gave us the following information and sources:

Anny Löw lived at Hörlgasse 5, on floor 2, until she moved to Hamburg on May 2, 1923. She was a bank clerk by profession. She married Norbert Otto Tugendhat on May 19, 1923 in Hamburg. They emigrated from Berlin Wilmersdorf to France on January 1, 1939. Anna’s first name was spelled in various different ways: Anna, Anni or Anny.

Norbert was born on November 10, 1896 in Grosseislingen/Göppingen/Wurtemberg21.

II) The historical silences in Anna’s story.

1) What are “historical silences”? And were there any such silences in Anna’s story?

Historical silences are the activities and traces of people who are not acknowledged and who no one talks about. According to Michelle Perrot, women have suffered from this historical silence until quite recently. Society, by not addressing it, creates the silence which, when it is broken, generates “too much noise”.

Our project involved research into Anna Tugendhat, but our investigations were limited due to the complete lack of records in the Convoy 77 archives: there were NONE. This [documentary] silence thus leads to an incomplete account of Anna’s life.

In order to find any information at all, we had to turn to the archives department in Vienna, where she was born under the name of Anna Löw, or Loew. She changed her name when she married Norbert Otto and then became Tugendhat, and yet we also come across the name Tugendhadt. All these names and spellings make it more difficult to carry out research. Not only that, but she was actually arrested in Monaco rather than in Nice, as some records suggest.

2) What does it mean to be a woman?

As far as I am concerned, a woman is a gender, just like a man. A woman should be equal to a man, that is to say, she should have the same rights and pay and be accepted as being on the same level as a man. Women have long been considered inferior to men. In the past, some women fought to have their rights respected, such as Joan of Arc, Georges Sand and many others. Nowadays, the situation has evolved, and their rights are more widely recognized, but in some countries, they are still bound by different rules. Our work was about a woman called Anna Tugendhat.

3) What particular types of violence did Anna experience? And women in general?

Anna was mentally abused in particular:

- She suffered pressure and stress brought on by the fear of the Nazis.

- She had to flee from her home country, Austria, due to persecution.

- Her husband, Norbert, died in a concentration camp.

Anna was also a woman deported to an extermination camp, Auschwitz, where she was murdered because she was considered no longer young enough to work. She was only 50 years old.

There are several different types of violence specific to women that arose during and after the Second World War. They were created in particular by Nazi ideology, which refers, for example, to feminism as a Jewish invention. The Nazis turned women into baby machines or made them have abortions or sterilized them. If women were too weak or old, they were taken directly to extermination camps to be killed. Women were never thought of as being strong. During and after the war, there were many cases of rape, torture, threatening behavior, and women being shorn of their hair. Women were not taken seriously and were treated as prostitutes when they complained, unless they were the victims of foreign rapists.

Jewish women, protesters and resistance fighters were sent to ghettos, concentration camps or extermination camps.

After the war, silence prevailed.

Women underwent atrocious experiments with the aim of sterilizing them. Many women suffered with visible signs of organ inflammation. One of the experiments involved sterilization using X-rays. The women came back in a terrible state, suffering from vomiting and abdominal pain. Some were burned by the X-rays. Also, Nazi doctors removed one ovary at first and the second one sometime later. In addition, in the concentration camps, mothers were separated from their children, so were also tortured psychologically. Some of them were taken to the gas chambers to be killed as soon as they got off the train.

Women in the camps had various difficulties with menstruation. When they had their periods, they felt ashamed, but some testimonies mention that having their period saved them from being raped because the Nazis viewed them as dirty.

In addition, poor hygiene caused infections that sometimes led to surgery. Women also stopped menstruating due to inadequate nutrition, which could leave them sterile for life. They used cloths as sanitary protection but had very few of them and they were not able to keep them clean.

4) The roles of women involved in or opposed to the extermination process:

Anna and her husband Norbert were involved in the Resistance, particularly with passport smuggling in order to help stateless Jews to escape.

Women also played an important role in the resistance movement, including Danielle Casanova and Simone Michel-Levy. The women were mainly liaison officers for resistance groups, often delivering and distributing newspapers and leaflets. They also provided information on troop movements. At the time of the Liberation, they were excluded from armed combat. The role of women in the Resistance was downplayed. Anna Tugendhat was able to see such women working in Auschwitz because she was there in person.

Nearly 500,000 German women were in the Wehrmacht and 3,500 were auxiliaries in the SS, mainly as camp guards (SS Aufseherin). A small number of women were attracted by the ideology or modernizing aspects of the regime. A few women were in the “executioners” world, such as the guards in the “death camps”, who collaborated in the overall system of killing and selection. Women did not, however, participate in the actual killing operations.

Women were also victims, especially through prostitution related to the military. For the Nazis, women were perceived only as procreators. In Mein Kampf, Hitler advocated sterilizing Jewish women. In 1933, the regime passed demographic legislation and set targets for the forced sterilization of hundreds of thousands of people. 90% of women died during the operations. “Eugenic” abortion was also performed on so-called “undesirable” women. These were the beginnings of the genocidal policy.

5) How does your work contribute to keeping the memory of the deportation alive? And that of Anna?

Our work helps to keep alive the memory of the deportation and of the deportees by not forgetting that they existed. As a result of our efforts, we can retrace a part of their history and also history in general. Added to this is an increase in awareness and the emergence of new thinking, in particular feminism with regard to the Holocaust. This is part of Women’s studies, which essentially retraces the history of women, and it includes conferences and the emergence of academic bodies.

Anna’s story can now be passed on to others and thus contribute to the memory of the deportation, the deportees and the women.

6) Can you list some adjectives to describe Anna’s life?

REBELLIOUS, DEHUMANIZED, ABUSED, HELLISH.

7) Which books in the library provide an insight into Anna’s life?

- Femmes en résistance, Volume 4: Mila Racine: a story in which Mila has the same idea as Anna, with her fake passports, and helps children to cross the border in secret.

- Dites-le à vos enfants by Stéphane Bruchfeld and Paul A. Levine. This book tells the story of women and children who were deemed incapable and destined to die, like Anna.

- La lettre à Conrad by Fred Uhlman, because both Anna and Conrad were involved in the resistance against Hitler.

- Annette, une épopée, by Anne Weber. Like Annette, the main character in the book, Anna participated in the resistance by selling false passports.

III) The exhibition in the library: pooling and presentation of students’ work on all 6 investigations, school outings, testimonies, visuals, sources compared to historical silences.

IV) Students’ observations

V) The investigation, translated into German: Die Ermittlung ins Deutsche übersetzt.

1) Wie viele Dokumente über Anna Tugendhat hattet ihr am Anfang der Arbeit? Was habt ihr dank diesen Dokumenten erfahren?

Ganz am Anfang hatten wir überhaupt keine Dokumente auf der Website www.convoi77.org über Anna Tugendhat zur Verfügung. Wir haben uns ernsthaft gefragt, ob sie wirklich existiert hat!

2) Was habt ihr denn herausgefunden?

Wir haben Folgendes herausgefunden: Anna LÖW oder LOEW ist am 2.September 1894 in Wien geboren. Ihr Vater war Emil Löwund ihre Mutter war Julie Löw, geborene Arnstein. Sie hatte 3 Geschwister:

– Robert, am 1.August 1893 geboren,

– Otto, am 13.Mai 1896 geboren,

– Amalia, am 7.August 1900 geboren.

Laut Wolfgang SCHELLENBACHER, der beim DÖW arbeitet, sind alle Kinder in Wien geboren, obwohl die Hochzeit nicht in Wien stattfand.

Nachdem Deutschland Österreich annektiert hat, ist sie nach Frankreich geflohen und wurde in Monaco von der deutschen Polizei verhaftet. Sie hat dort in der Nähe vom Hôtel de Paris gewohnt.

Sie wurde vom Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei nach Drancy geschickt.

Als sie festgenommen wurde, hatte sie dabei:

– einen wertvollen Ring mit Gold und Perlen,

– 3 Anhänger,

– eine Perlenhalskette,

– eine Perlenbrosche

– ein Scheckheft (Crédit foncier de Monaco).

Sie wurde am 31. Juli 1944 mit dem Konvoi 77 nach Auschwitz-Birkenau deportiert.

An der Pariser Shoah Namenswand kann man direkt neben Annas Name den Namen von Norbert lesen. Wir haben angenommen, dass es sich um ein Familienmitglied handelt. Auf den (vom 16. Juli 1943 bis zum 12. Dezember 1944 datierten) Listen findet man auch die Vornamen von Anna und Norbert, aber diesmal anders geschrieben. Michael BLOCHE hat bestätigt, dass Norbert tatsächlich ihr Mann ist.

Wir haben uns dafür entschieden, über Norbert weiter zu recherchieren.

Was Norbert betrifft, haben wir also andere wichtige Informationen (unter anderen auf der Website https://www.bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch/) gefunden:

Norbert ist am 10. November 1894 in Großeislingen/Göppingen/Württemberg geboren.

Er hatte drei Halbschwestern: Lieselotte TUGENDHAT, Anna Marie TUGENDHAT, Annaliese TUGENDHAT. Sein Vater, Bruno Bronislaw TUGENDHAT, hat Friederike Fritzi TUGENDHAT geheiratet. Norbert hat die deutsche Staatsangehörigkeit, aber für die Nazis war er nur ein Jude.

Er hat in Berlin (Wilmersdorf) gelebt. Er ist erst am 01. Januar 1939 nach Frankreich geflohen. Dort hat er wohnte in Paris (11 rue d‘Odessa) gewohnt. Er reiste viel und ist mehrmals nach Monaco gefahren, um Anna zu besuchen. In Monaco war er am 13. und am 14. September 1943, in der Nacht vom 16. September auf 17.September 1943, vom 1. Oktober bis zum 7.Oktober 1943, vom 9. Oktober bis zum 10. Oktober 1943 und vom 13. Oktober bis zum 15. Oktober 1943.

Die Gestapo in Koblenz hat sich für ihn interessiert und er war ständig unter Überwahrung.

Er wurde zweimal verhaftet und nach Drancy geschickt, und zwar am 14. Januar 1944 und am 6. Mai 1944. Als er festgenommen wurde, hatte er – wie Anna – viele Schmuckstücke und viele verschiedene Fremdwährungen dabei. Wir haben 2 Hypothesen formuliert: entweder war er wohlhabend oder er schmuggelte Waren.

Er wurde am 31. Juli 1944 von Drancy nach Auschwitz-Birkenau (Oswiecim), Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslager, deportiert. Er ist danach in Hailfingen-Tailfingen (Außenlager des KZ Natzweiler-Struthof) angekommen und trug als Häftling die Nummer 40967. Diese Nummer wurde ihm am 16. oder 17. November 1944 zugeteilt und er wurde unter den Kategorien „Schutzhaft“ und „Jude“ registriert. Er ist am 02. Dezember 1944 um 8.00 Uhr morgens an einer Herzinsuffizienz in Hailfingen-Tailfingen, Außenlager des KZ Natzweiler-Struthof gestorben. Er trug die Nummer 353. Er wurde am 5. Dezember 1944 im Krematorium in Reutlingen verbrannt.

Anna wurde mit dem Konvoi 77 deportiert. Sie hat nicht überlebt.

Sie wurde als „Jüdin“ verhaftet und wurde am 31. Juli 1944 nach Auschwitz-Birkenau deportiert.

Ein Gedenkstein wurde am Donnerstag, den 27. August 2015, im Friedhof von Monaco enthüllt. Zu dieser Enthüllung waren SAS der Prinz, Vertreter der zivilen und religiösen Behörden, Nachfolger und Offizielle der jüdischen Organisationen eingeladen.

3) Hättet ihr gedacht, dass ihr so viele Informationen finden würdet?

Wir dachten nicht, dass wir so viel herausfinden würden!

4) Inwiefern ist eure Arbeit für Anna wichtig?

Unsere Aufgabe bestand darin, Spuren von Anna wiederzufinden, damit wir Annas Andenken in Ehren halten können, damit wir eine Erinnerung von ihr haben, damit sie endlich in Frieden ruhen kann.

Online-Treffen am 22. März mit Michael Bloche, directeur de la mission de préfiguration des archives nationales de Monaco:

– Anna besuchte jeden Tag das Casino: sie war wahrscheinlich wohlhabend.

– Norbert wurde vor Anna in Paris verhaftet, und zwar aus zwei Gründen: er war Jude und er fälschte in Südfrankreich Ausweise (möglicherweise für heimatlose Juden).

Anna wurde wegen gefälschter Papiere verhaftet: sie trug den Namen von Adèle MONTAUDON.

Quelle: Direction de la Sûreté publique (DSP) : 031179 (dossier individuel d’Anna Tugendhat)/111000 (dossier collectif dans lequel le dossier individuel est classé).

Wir stellen eine Hypothese auf: Vielleicht war das Casino ein Ort, wo sich WiderstandskämpferInnen trafen oder man auf dem Schwarzmarkt Ausweise kaufen konnte.

Online-Treffen am 3. Mai 2022 mit dem Bundesgymnasium 19 (Gymnasiumstr. 83, 1190 Wien):

Die Wiener SchülerInnen des Wahlpflichtfachs Geschichte des G19 haben unter der Leitung von Martin Krist eine sehr hilfreiche Arbeit geleistet und uns bedeutsame Informationen weitergegeben.

Hier ist eine Synthese, die Martin Krist uns am 10. Mai per Mail geschickt hat.

Anny Löw wohnte bis zu ihrer Abreise nach Hamburg am 2. Mai 1923 in der Hörlgasse 5, 2. Stock.

Von Beruf war sie Bankbeamtin.

Sie heiratete am 19. Mai 1923 in Hamburg Norbert Otto Tugendhat.

Die beiden emigrierten von Berlin Wilmersdorf am 1. Jänner 1939 nach Frankreich.

Anna/Anni/Anny Tugendhat geb. Löw wurde gemeinsam mit ihrem Mann am 31. Juli von Drancy nach Auschwitz-Birkenau deportiert.

An der Wiener Shoah Namenswand der ermordeten österreichischen Jüdinnen und Juden findet sich ihr Name (siehe dazu die beiden angehängten Fotos)

ZUSÄTZLICHES ZU Norbert Tugendhat:

Tätowierte Nr. in Auschwitz-Birkenau: B 3943

Von Auschwitz-Birkenau am 28. Oktober 1944 ins KZ Stutthof deportiert.

Ab November 1944: Hailfingen-Tailfingen, Außenlager des KZ Natzweiler-Struthof

Dort gestorben/ermordet am 02. Dezember 1944

BRAVO to Myriam, Razanne, Yousra, Kylian, Evan, Lilyann, Isaline and Marine with the guidance of Ms. Laetitia Bouillon, their German teacher and Ms. Morgane Boutant, their History and Geography teacher.

1 Anna’s birth certificate, ref Cm. 2152/1894, Archives of the Jewish community of Vienna, obtained in response to an email sent by the students on January 19, 2022 to the DÖW documentation center of the Austrian resistance, according to Wolfgang Schellenbacher and Rz 2152/1894, archives of the IKG Vienna in response to an email sent by the students on January 25, 2022 according to Susanne Uslu-Pauer.

2 Information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on January 19, 2022 to the DÖW documentation center of the Austrian resistance, according to Wolfgang Schellenbacher.

3 Information obtained in response to an e-mail sent on December 1, 2021 to the archives of Monaco according to Michael Bloche.

4 Shoah Memorial page for Anna Tugendhat

5 Shoah Memorial page for Anna Tugendhat

6 Shoah Memorial page for Anna Tugendhat

7 https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=id:586003

8 Information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 1, 2021 to the National Archives of Monaco according to Michael Bloche.

9 Information obtained in response to an email sent by students on December 1, 2021 to the Arolsen archives according to Sigrid Hebe.

10 Information obtained in response to an email sent by students on December 1, 2021 to the Arolsen archives according to Sigrid Hebe.

11 Information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 6, 2021 to the archives of the Société des Bains de Mer de Monaco according to Charlotte Lubert.

12 Shoah Memorial page for Norbert Tugendhat

13 Information obtained in response to an email sent by students on December 1, 2021 to the Arolsen archives according to Sigrid Hebe.

14 Information obtained in response to an email sent by students on December 1, 2021 to the Arolsen archives according to Sigrid Hebe.

15 Information obtained in response to an email sent by students on December 1, 2021 to the Arolsen archives according to Sigrid Hebe.

16 Information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 1, 2021 to the National Archives of Monaco according to Michael Bloche.

17 Information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 1, 2021 to the National Archives of Monaco according to Michael Bloche.

18https://www.palais.mc/en/news/h-s-h-prince-albert-ii/event/2015/august/ceremonie-en-memoire-des-juifs-de-monaco-deportes-pendant-la-seconde-guerre-mondiale-3324.html and information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 1, 2021 to the National Archives of Monaco according to Michael Bloche.

19https://www.monacomatin.mc/histoire/il-y-a-peu-de-temoins-en-vie-une-ong-juive-veut-acceder-aux-archives-de-la-guerre-a-monaco-442108 and information obtained in response to an email sent by the students on December 1, 2021 to the National Archives of Monaco according to Michael Bloche.

20 Public Safety directorate (DSP) : 031179 (Anna Tugendhat’s individual file)/111000 (collective file in which the individual file is kept).

21 Martin KRIST sources:

Source reference for the registration form: WSTLA, registration file

Photos: Martin Krist.

More information about Anny and Norbert Tugendhat:

https://www.bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch/

https://www.gedenkstaettenverbund-gna.org/images/downloads/gedenkstaettenrundschau/gr_16_webO.pdf P.29 – 31

https://www.bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch/

22: Historical silences sources:

-Titiou LECOQ, Les grandes oubliées : Pourquoi l’Histoire a effacé les femmes, l’Iconoclaste, Paris, 2021. Chapitre 15 : Deuxième Guerre mondiale: le rôle des femmes minimisé.

-Michelle PERROT, Les femmes ou les silences de l’Histoire, Flammarion, Paris, 2020. Quatrième de couverture.

-Association MNEMOSYNE, Coordination Geneviève DERMENJIAN, Irène JAMI, Annie ROUQUIER, Françoise THEBAUD, La place des femmes dans l’histoire, une histoire mixte, Belin, Paris, 2010. Chapitre : Femmes et hommes dans les guerres, les démocraties et les totalitarismes (1914-1945).

-Simone de BEAUVOIR, Le deuxième sexe, Tome I, Gallimard, Paris, 1949. Quatrième de couverture.

-Jo-Ann OWUSU, Les menstruations et l’holocauste History Today, numéro 69, mis en ligne le 5 mai 2019. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/menstruation-and-holocaust

-Isabelle ERNOT, Le genre en guerre. « Exécutrices, victimes, témoins », Genre & Histoire, numéro 15, mis en ligne le 30 septembre 2015. https://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/2218,

-Isabelle ERNOT, Le genre en guerre : « Women and/in the Holocaust » : à la croisée des Women’s-Gender et Holocaust Studies (Années 1980-2010) », Genre & Histoire, numéro 15, mis en ligne le 30 septembre 2015. http://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/2223

Français

Français Polski

Polski