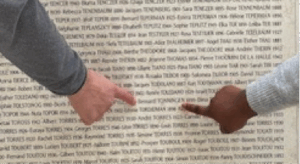

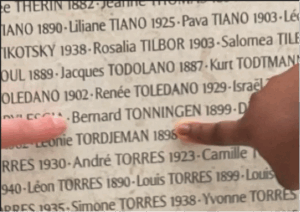

Bernard TONNINGEN (1899-1944)

Bernard Tonningen was not just a file reference…

Bernard Tonningen had a name, a face and a shattered life.

I/ Raised in Amsterdam

Bernard Tonningen was born on October 25, 1899 in Amsterdam in the Netherlands. He probably lived at Tolstraat 103 II, his father’s last known address, together with his older brother, Alexander Tonningen (1898-1943) and his parents, Salomon Tonningen (1871-1943)[1] and Rachel Voorzanger (1872-1912), who were married in 1896.

This street, part of the De Pijp district, was home to many Jewish families. An urban area, it was built in the late 19th century in the south of Amsterdam to accommodate the city’s rapidly increasing population. In the first half of the 20th century, De Pijp was a multicultural neighborhood with a sizeable Jewish community.

Plan of Amsterdam in 1914, showing the De Pijp district

In 1892, a huge synagogue was built in the Rue Gerard Doustraat, and it soon became one of the district’s main focal points. To this day, it remains the city’s oldest Ashkenazi synagogue.

The Gerard Dou Synagogue in the De Pijp district

A diamond polisher by the name of van Asscher lived on the same street as Bernard Tonningen, and this area is also known as the Diamantbuurt (diamond district). The Albert Cuypmarkt was a weekly market on which many Jewish merchants sold their wares. The market is still one of Amsterdam’s largest, but the Jewish contingent faded away after the war. Here we should remind ourselves of just how large Amsterdam’s long-standing Jewish community was: there were once some 80,000 Jews in the city. Even now, Amsterdam is often called “Mokum”, which means “place” in Yiddish. Even before the 19th century, Amsterdam was home to various different Jewish communities. Their occupations, businesses, social organizations, traditions, markets and neighborhoods gave 20th century Amsterdam its own distinctive feel.

The Jews migrated to the Netherlands in two main phases. The first, which began in the 16th century, was when Jewish communities expelled from Portugal arrived in Amsterdam. They built the city’s first synagogue, the Esnoga, in 1675. The second was in the 1930s, when many German and Eastern European Jews (including Anne Frank’s family) fled persecution in their home countries.

After the Holocaust, there were only 5,000 Jews left in Amsterdam.

According to our research and conclusions, Bernard Tonningen most likely attended either the Wilhelmina Catharinaschool (at Weteringschans 263) or the Herman Elteschool (on Nieuwe Keizersgracht), both of which were near his home and attended by many Jewish children. Neither of these Jewish schools is still in existence today.

Bernard Tonningen thus led a typical Amsterdam boy’s life, in a working-class neighborhood in a city as yet untouched by the chaos of the Great War, which set Europe alight in the summer of 1914.

Bernard Tonningen must have done well in school because he went to high school, which was not the norm at the time, and passed his HBS. This was the equivalent of today’s Havo/VWO in the Netherlands, the baccalaureate in France, A-levels in the UK and the High School Diploma in the US.

When he turned 18, in 1918, he was called up to do his military service. His brother had already done his, so was not called up again. Bernard also tried to avoid going by saying he had a deformed foot, but the physician was not convinced, so he had to do it. He expressed an interest in joining the artillery in Amsterdam if he was mobilized. His army service record [2] states that he was just under 5’7” (1.69 m) tall.

On August 1, 1925, at the age of 25, Bernard Tonningen was crossed off the list or residents in the city of Amsterdam, this being a year after he had arrived in France. The young Dutchman had emigrated to France and was now a Parisian.

II/ A young man in Paris between the wars, 1924-1939

In 1924, Bernard Tonningen had thus decided to leave the Netherlands and move to France, where he set up home 3 bis, rue des Rosiers, in the Marais neighborhood of Paris [3]. At the time, it was a working-class neighborhood, a great place to meet people, with a bustling Jewish community and a lively intellectual scene. The young Bernard Tonningen, who by this time was a chartered accountant, began to build a new life for himself.

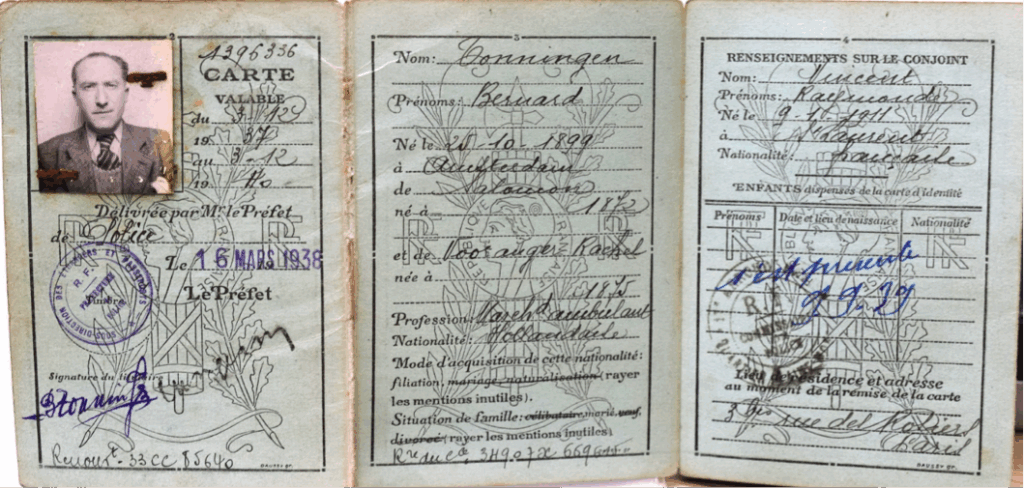

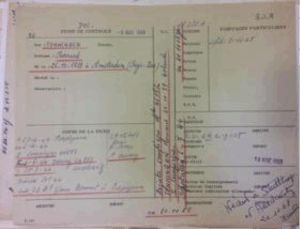

Bernard Tonningen’s foreigner’s identity card, issued in 1938, ref. AD 21 w 250

The 1920s and 1930s marked a time of great change and renewed optimism, but also of increasing social unrest. From 1933 onwards, Nazism cast a dark shadow over Europe. In France, the threat of the far-right movement in 1934 was countered for a time when the Front Populaire (Popular Front, a broad left alliance) won the election in 1936.

3 bis rue des Rosiers in the Marais neighborhood of Paris

As this was all happening, Bernard Tonningen appears to have continued to live and work in Paris, immersing himself in the capital’s cultural and social scene. His foreigner’s identity card, issued in 1938, states that at that time he was a street vendor and was married to a French woman called Raymonde Vincent[4].

III/ Paris in wartime: a foreigner committed to defending France

When war broke out on September 3, 1939, Bernard Tonningen, despite being a foreigner, wanted to defend his adopted country. He was by then living at 24, rue Cardinet in the 17th district of Paris.

On October 12, he reported to the French Foreign Legion’s Special foreigners’ recruitment center at Porte Clignancourt, not to join the Legion itself, but more likely to join one of the three regiments of the RMVE (Regiments de Marche de Volontaires Etrangers, or Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers). He was one of 40,000 foreign Jews who enlisted voluntarily. This was a huge number, given that in 1939, the total population of foreign Jews in France was estimated at 150,000. It reflects a keen awareness of the danger looming over France as a country and its Jewish communities in particular. Bernard Tonningen may well have been a Parisian just like so many other men, but he was also a Dutch Jew who chose to fight for a country that was not even his own. This must have felt personal to him: how could he remain indifferent to the oppression and tyranny of an anti-Semitic, racist regime that was threatening not only France, but also his native Netherlands?

After the French army was defeated and the armistice signed on June 22, 1940, he was demobilized. This marked the end of his involvement in the war, but not the end of his commitment to the cause.

IV/ A foreigner in the Free zone: life and trying to survive under the Vichy regime

After he was demobilized, Bernard Tonningen left Paris and headed for the south of France. We assume that he did so to avoid living in German-occupied Paris and to seek shelter in the so-called “Free Zone”. Run by Marshal Pétain’s government, the free zone, in theory, was a safe haven for Bernard Tonningen, a foreigner who had served the country in 1939. He therefore relocated to the Aveyron department, perhaps to put as much distance as possible between himself and the xenophobic and anti-Semitic persecution already being perpetrated by the Vichy regime.

The various records we examined reveal that Bernard Tonningen, as a foreigner, registered himself with the authorities as was required by law and worked various short-term jobs, none of which offered any security.

In early 1941, he was living in Saint-Côme-d’Olt, where he rented a room in the Cabanettes hotel, and working a few miles away in Espalion.

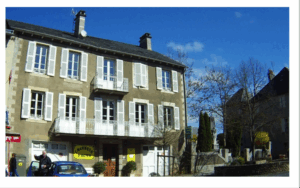

The Cabanettes hotel in Saint-Côme-d’Olt

The French Ministry of Labor had authorized him to work. He started out as a production manager in a company run by Simon Affre in Espalion, then in March took a job as a “road laborer” with a roadworks company, as confirmed by an engineer, Pierre Godeux. At this point, he applied to have his foreign worker’s identity card renewed. He was still living in Saint-Côme, and was registered as a street vendor.

In November 1941, when he completed the Ministry of Labor’s information form in order to renew his identity card, he declared that he was an industrial worker and laborer for the CFD mining company in Decazeville, Aveyron.

Each time he renewed his identity card, the authorities recorded and highlighted the fact that in 1939, he had volunteered to serve in the army as a foreigner, which for a time enabled him to avoid being drafted into one of the groupements de travailleurs étrangers (foreign workers’ groups), which all foreigners were normally obliged to join. These groups had been set up under a French law enacted in September 27, 1940, relating to “foreigners who are surplus to requirements in the national economy”.

It is clear that Bernard Tonningen did everything he could to comply with the law and to remain in work, not only to make himself indispensable but also to survive in an environment that was becoming increasingly hostile towards foreigners.

V/ A foreign Jew, his life in danger

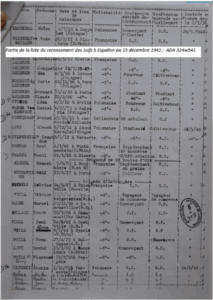

For Bernard Tonningen, the turning point came on December 15, 1941, when, in accordance a law enacted on June 2, 1941, which required the Jews to take part in a census, he went to register at the town hall in Espalion[5]. As far as the Vichy authorities were concerned, he was no longer just a foreigner to be kept under surveillance, but a Jew, and thus an undesirable person to be eliminated. Having identified himself as a foreign Jew, he was now in grave danger.

Bernard Tonningen’s name on the list of Jews in Espalion, in the Aveyron department of France after he took part in the census on December 15, 1941. ADA324 w 541

Although his position was becoming increasingly precarious, Bernard Tonningen continued to find ways to adapt and survive in a world that seemed determined to crush him. He was soon forced to join one of the foreign workers’ groups that we mentioned earlier, and was assigned to several different workplaces and construction sites, according to their demand for manpower (Espalion, Saint-Julien de Piganiol and Entraygues).

VI/ A resistance fighter in the clutches of the Nazis

We do not know why or how, but Bernard Tonningen left Espalion and went to Perpignan, in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France, where he lived at 23, boulevard Jean-Bourrat. Might he have gone there to join his wife, or perhaps to be nearer to the Spanish border? We do not know who Bernard married, nor when or where the wedding took place.

On June 2, 1944, the Gestapo arrested Bernard in Perpignan on the grounds that he was an “Israelite [Jew] involved in resistance activities”. He must therefore have been a member of the Resistance, which ties in with what he had been doing since 1939, but we have no further details about what exactly he did. Nor do we currently know any more about the circumstances of his arrest.

He was initially interned at the citadel in Perpignan, which the Nazis had taken over in late 1942. Run by the SIPO-SD (Sicherheitspolizei), which included the Gestapo, the citadel played a key part in the roundups and arrests in the south of France. The prisoners held there were routinely tortured, and then either executed or deported. On the same day, Samuel Barouh, a young Jewish resistance fighter who had also taken refuge in Perpignan during the war, was arrested and taken to Gestapo headquarters.

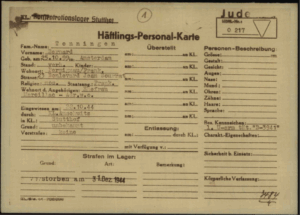

On June 12, after ten terrifying days, Bernard Tonningen was transferred from Perpignan to the Royallieu-Compiègne camp, some 40 miles northeast of Paris. Also known as Frontstalag 122, the camp had been set up in June 1941 and was run by the Nazi SD. It was used mainly as an internment and transit center for resistance fighters and political opponents, but many Jews and gypsies were also held there. When Bernard arrived in the camp, he was assigned prisoner number 41,082 and was imprisoned as both a Resistance fighter and a Jew. He was one of 54,000 people interned there, including Samuel Barouh.

Bernard Tonningen was probably held in zone C, the so-called “Jewish camp”, where arrested Jews were segregated from other prisoners, but it is impossible to prove this: the Germans later destroyed all the camp records.

VII/ Deported on Convoy 77 and murdered in Auschwitz

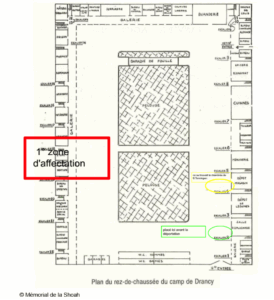

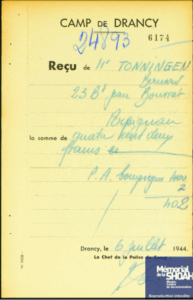

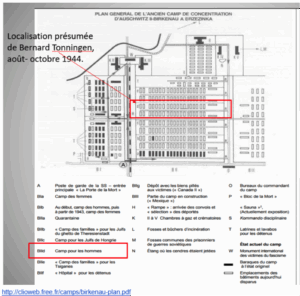

On July 6, 1944, Bernard Tonningen was transferred to Drancy internment camp on the outskirts of Paris. Initially built as a modern, low-rent housing estate, in 1942, Drancy became the main transit center for Jews arrested in France. There, they waited in appalling conditions until they were sent to an almost certain death. When he arrived in Drancy, Bernard was assigned yet another prisoner number: 24893. He was then searched and made to “deposit” the 450 francs he was carrying, for which he was given a receipt. This demonstrates the way in which such administrative procedures were used to give the impression of normality, to disguise what was really happening and conceal the authorities’ crimes. Bernard was first sent to room 4 on staircase 18, then transferred to staircase 4 until the day before Convoy 77 was due to leave, at which point he was moved to staircase 2, near the main gate. Two or three days before the transports left, the people listed for deportation were assigned to separate rooms and staircases from the rest of the internees, and were no longer allowed to have any contact with them.

Bernard Tonningen’s receipt from Drancy camp © Shoah Memorial, Paris

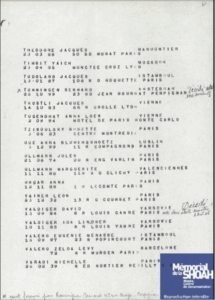

Bernard Tonningen’s name on the Convoy 77 deportation list © Shoah Memorial, Paris

On July 31, 1944, Bernard Tonningen, as well as Samuel Barouh, were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on the last convoy to leave from Bobigny station. The journey east took over three days, in dehumanizing conditions. When the 1306 deportees arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 986 men, women and children were sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered, never even entering the camp. The prisoners selected for forced labor (291 men and 183 women) were taken into the camp, registered and tattooed.

Bernard Tonningen had the number B-3941 tattooed on his forearm. According to a testimony written in February 1946 by Hugo Perez, a Convoy 75 survivor who also came from Perpignan, and lived through those terrible days with Bernard Tonningen, he was assigned to a barrack in Block 2 and to a Kommando that carried out earthworks (one of the toughest work groups). During regular selections, the SS sent the weakest, most exhausted deportees to the gas chambers.

Hugo Perez also testified that in late October, 1944, Bernard Tonningen’s name was “drawn by lot” during a selection process involving some 850 men. Having witnessed the scene, Hugo Perez said that Bernard was taken to the gas chambers in a truck, and that the truck came back carrying on the men’s “uniforms”. It was on the basis of this testimony that, after the war, at the request of a Dutch notary who was trying to settle an estate in Amsterdam, an official death certificate was issued. The date of death was recorded as the end of October 1944.

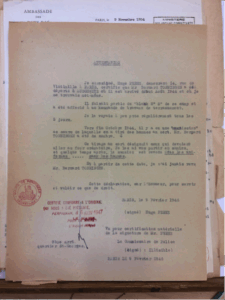

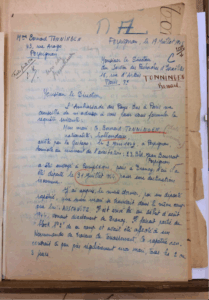

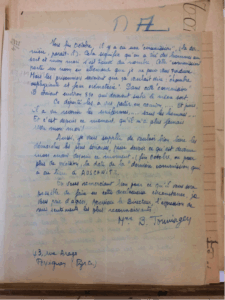

Pages from dossier 21 P 544 464 @ Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

However, Bernard Tonningen was not in fact sent to his death as Hugo Perez believed. On October 28, he was transferred to the Stutthof concentration camp, also in northern Poland, along with a large number of other prisoners[6]. This camp was used to supply slave labor for companies in the surrounding area.

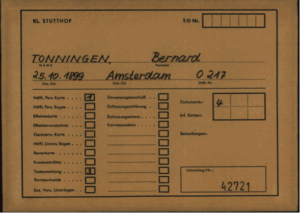

Record of Bernard Tonningen in the Stutthof camp @ Bad Arolsen archives

Page from dossier 21 P 544 464 @ Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

In 1968, a summary was drawn up of Bernard Tonningen’s journey through the camps. It lists his Compiègne serial number as 41,082. The date of his death is wrong, as it is based on a testimony that turned out to be inaccurate. It was not until the Bad Arolsen archives were made available, decades later, that the full details of what happened to him became known.

Bernard Tonningen’s record card from the Stutthof camp @ Bad Arolsen archives

In Stutthof, Bernard Tonningen was assigned the number 0217 and selected for forced labor as a metalworker. Living conditions there were appalling: deprivation, exhaustion and physical abuse. The Stutthof camp archives contain a death certificate stating that he died of “a heart condition” at 7:35 a.m. on December 31, 1944. However, we know that in reality, he almost certainly died of exhaustion and malnutrition. He was 44 years old.

This is evidence of the cynical attitude of the Nazi authorities, for although they made no secret of their intention to annihilate the Jews, the paperwork was designed to cover up the reality of their crimes.

On January 2, 1945, the crematorium manager drew up a cremation certificate for Bernard Tonningen’s body. His death demonstrates the scale of Nazi barbarism and the deliberate, cruel destruction of millions of innocent lives.

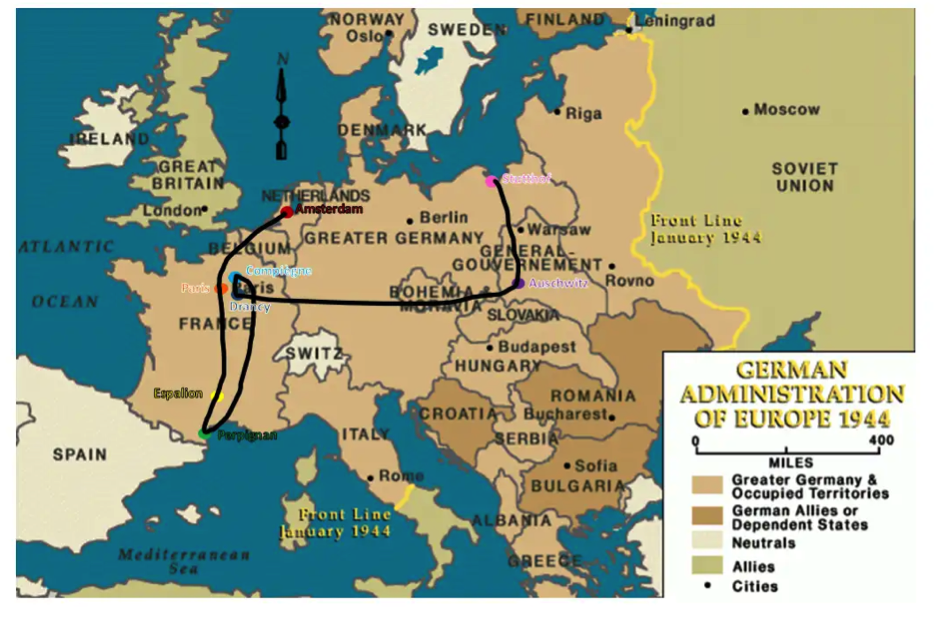

Bernard Tonningen’s journey 1924-1944

Bernard Tonningen’s journey 1924-1944

VIII/ The Tonningen family, shattered and annihilated during the Holocaust

In a deeply moving letter written on July 19, 1945, Bernard Tonningen’s wife, having no news of her deported husband, contacted the Service des Recherches d’Israélites (Jewish tracing service) to ask if they could provide any information about him. We understand that she also spoke to Hugo Perez, who was also deported on Convoy 77 and survived, and who was in Auschwitz with her husband. She therefore knew where her husband had been deported to, but did not know what had happened to him, and still hoped that he would return home. We found no other record of her.

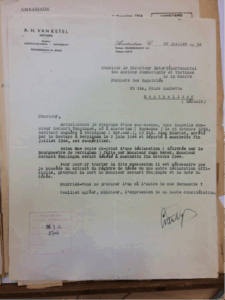

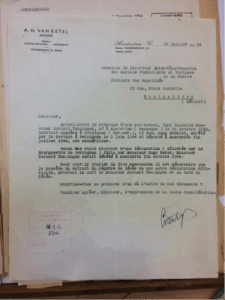

Letter from Bernard Tonningen’s wife asking for information about what had become of her husband , in which she explained that Hugo Perez had told her his version of Bernard’s fate Source: dossier 21 P 544 464. @ Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

This tragedy is made worse by the annihilation of Bernard Tonningen’s family in the Netherlands. His father, Salomon Tonningen, and his brother, Alexander Tonningen, were also victims of the Holocaust. They were both diamond cutters, married and lived in Amsterdam. The Wehrmacht occupied the city in the spring of 1940, and the SS soon took charge and began implementing the Nazi policy of anti-Semitic persecution. They were arrested in the spring of 1943 and taken to the Westerbork transit camp in the north of the Netherlands.

Salomon, Bernard’s father, was deported to Sobibor together with his second wife, Judith Tonningen-Engelander, on April, 1943. They were killed as soon as they arrived there, on April 9.

Alexander, Bernard’s older brother, who was born on May 20, 1898 in Amsterdam, had held a number of different jobs (diamond polisher, accountant and office clerk). Military records show that he served for many years in the artillery. He and his wife, Susanna Tonningen-Leuw, who was born on June 14, 1879, were deported to Sobibor on June 1, 1943, and they too were murdered soon after the transport arrived, on June 4.

After the war, the question arose about who should inherit the Tonningen family’s property. Maître van Ketel, a notary in Amsterdam, contacted the Dutch embassy in France and the relevant French ministries to request information and a death certificate in order to settle an estate in Amsterdam of which Bernard was one of the heirs. We therefore surmise that there must have been other heirs as well, but to date, we have been unable to find out anything more.

Dossier 21 P 544 464 @ Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

Dossier 21 P 544 464 @ Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

Bernard Tonningen is no longer merely a name inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, hidden among those of 75,568 other Jews who were deported from France. In this biography, fragments of his life are revealed and remain a testimony to a life full of hope and hardship, which was ultimately shattered by the Nazis.

For us, a group of students at the Vincent Van Gogh French high school in The Hague, in the Netherlands, this investigation has been extremely rewarding and often moving experience. It was therefore an extremely rewarding and often moving investigation. We hope that our meagre contribution will help not only to commemorate Mr. Tonningen, but also help to ensure that the millions of Jews persecuted and murdered during the Holocaust will never be forgotten.

Constance, Anna, Charlotte, Azhar, Eva, Saoussane, Anaïs, Maxime, Maxence M, Maxence D, Hippolyte, Hannah, Léonard, Augustin, Clarisse and Clément, 12th grade students from the Vincent Van Gogh French high school in the Netherlands.

We would like to thank Claire Podetti for her expert advice and Mr. Massbaum, the author of Aveyron-Drancy-Auschwitz (1940-1944): récits individuels par communes des 391 Juifs déportés ayant vécu en Aveyron (Aveyron-Drancy-Auschwitz (1940-1944 : individual accounts by commune of the 391 deported Jews who were living in Aveyron), who kindly provided us with some invaluable documentation relating to Bernard Tonningen.

Sources:

- Bad Arolsen archives: KL STUTTHOF

- Dossier 21 P 544 364, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- Digital Joods Monument https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/167405/salomon-tonningen

- National archives of the Netherlands

- Simon Massbaum, Aveyron-Drancy-Auschwitz (1940-1944) : récits individuels par communes des 391 Juifs déportés ayant vécu en Aveyron,

- Association pour la mémoire des déportés juifs de l’Aveyron (Association for the memory of Jewish deportees from Aveyron)

- Fils et filles des déportés juifs de France (Sons and daughters of the Jewish deportees from France) 2022, preface by Serge Klarsfeld and Alexandre Doulut.

Notes & references

[1] Digital Joods Monument https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/167405/salomon-tonningen

[2] Open Archieven

Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Militieregisters

Part: 4427, Period: 1827-1940, Amsterdam, archive 5182, inventory number 4427

https://archief.amsterdam/inventarissen/scans/5182/2.2.2.2.1.202/start/120/limit/10/highlight/8

[3] Bernard Tonningen’s identity card, issued in 1938, AD 21 w 250 (26).

[4] Bernard Tonningen’s identity card, issued in 1938, AD 21 w 250 (26).

[5] There is a memorial plaque in Espalion dedicated to the 42 Jewish refugees – men, women and children – from the town and surrounding area, who were arrested and deported. Bernard’s name is on it.

[6] As were, at least from Convoy 77: Raphaël Caraco, Albert Cahan, Cadok Davidson, Etienne Moszer, Willy Fischer, Serge Fiskus Foder, Henri Frajenberg, Maurice Grinberg, François Grosz, Jacques Khinkis, Robert Kirschbaum, Maurice Kurnentz, Georges Machlis, André Malka, Henri Manewitz, Joseph Misreh, Simon Razon, (Maurice Minkowski was sent there on October 16), Jacques Reboah, Isaac/Jacques Roumi, Henri Saisier, Joseph Sieder and Norbert Tugendhat, according to Volker Mall’s review.

Français

Français Polski

Polski