Chaïm Israël BORYCKI

On the left, a photo of Charles Bory

Chaïm Borycki was born on November 2, 1902 in Szydlowiec, a town in Poland.

He was the son of Nusyn Borycki and Mirla Fryde.

Chaïm Borycki moved to France in 1919.

There he met Rachel Sosnovitch, who was born on July 11, 1906 in Warsaw. She was the daughter of Isaac Sosnovitch and Esther Brandla. They were married in Les Lilas, a suburb to the north east of Paris, on October 20, 1925. As from 1927, the couple lived at 176, rue de Noisy-le-Sec in Bagnolet.

Chaïm and Rachel were naturalized as French citizens according to a decree dated June 23, 1932.

Chaïm worked as a tailor. He operated from home and was listed in the Trade Register under the number 111.959.

Le couple had one child, Roger, who was born on May 28, 1933.

From October 1940, Chaïm became involved in anti-German propaganda by distributing leaflets and pamphlets that were printed in secret.

In 1941, he joined the National Front[1].

While distributing leaflets to workers, and encouraging them to sabotage the CICCA factory (Compagnie industrielle et commerciale du cycle et de l’automobile, or Industrial and commercial cycle and automobile company) at 135 Rue de Noisy-le-Sec in Les Lilas, he spotted a collaborator whose first name was Robert[2], who reported him to the German authorities.

The arrest

There is conflicting information about the exact location of his arrest.

According to two witnesses, Henri Dupuis[3] and a Ms. Truchart, Chaïm Borycki was arrested at the CICCA factory while distributing leaflets to the work force calling on them to engage in sabotage. Their testimonies both say that Mr. Borycki was arrested and dragged into a car and that a collaborator, Robert, was there at the time.

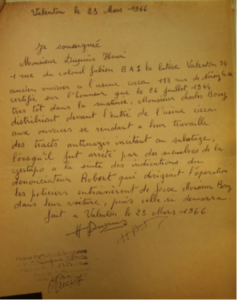

Testimony of Mr. Dupuis, a former worker at the CICCA factory, dated March 23, 1966

Chaïm Borycki’s own account of his arrest differs[4].

He said he had been given instructions to distribute leaflets at the CICCA factory, near his home, on July 26, 1944.

However, he spotted the collaborator, Robert, who was beckoning a black Gestapo car out of the Passage des Sablons, coming towards him with the intention of arresting him.

Mr. Borycki decided to flee because he was in possession of compromising documents that could have led to the arrest of other members of the Resistance. He went to his home, which was not far from the factory, locked himself in, and then destroyed the documents by burning them in his kitchen.

He stated that seven Gestapo officers[5] broke through his front door.

He said he was then driven to the Gestapo headquarters on rue des Saussaies in Paris[6] where he was interrogated in an attempt to get him to betray his fellow Resistance members.

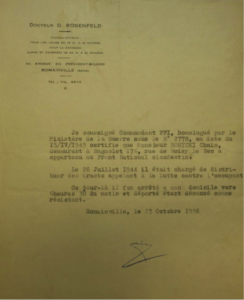

A Dr. Rosenfeld, an FFI[7] commander, also testified that Mr. Borycki was arrested at his home on July 26, 1944 in connection with his Resistance activities.

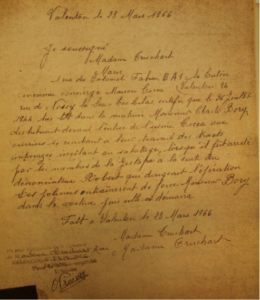

Testimony of Ms. Truchart, a former janitor at the CICCA factory, dated March 23, 1966.

Despite being threatened with being shot, Mr. Borycki refused to give any information about the network and was transferred to Drancy[8] the following day.

He was deported on July 31, 1945 on the last transport from Drancy, Convoy 77[9] to Auschwitz[10].

When he arrived, he was selected to work.

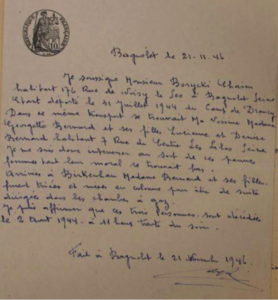

Mr. Borycki gave a very moving testimonial about the Bernard family on November 21, 1946.

Georgette Bernard, the mother, and her two daughters Denise and Lucienne, were on the same convoy and were murdered as soon as they arrived in Birkenau[11] on August 3, 1944[12].

After Auschwitz, he was sent to various other concentration camps: Stuttof[13], Buchenwald[14], Leipzig[15], et finally Terezín[16] in Czechoslovakia, from which he was liberated by the Russians in May 1945.

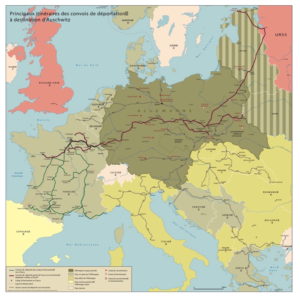

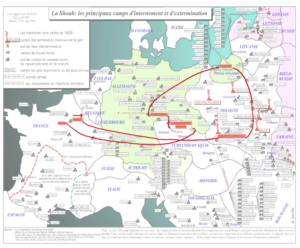

The journey to Auschwitz was horrific: about 950 miles (1500 km) of railroads, 53 hours travelling time and fifty or so train stations. Source: The Shoah Memorial in Paris

Chaïm Borycki’s itinerary. Source: The Shoah Memorial in Paris

On June 7, 1945, Chaïm Borycki was repatriated to France.

After returning to France, he began a long struggle[17] to be recognized as having been deported as a member of the Resistance and to be granted a pension.

He put together a series of documents and in June 1951 he applied to the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War for the status of deported Resistance fighter, which was repeatedly refused!!!

A long road to recognition

On September 17, 1947, Mr. Borycki received a certificate of deportation or internment issued by the director of the Bureau National de Recherches et Fichiers Internés et Déportés Politiques, the French National Bureau of Research and Files on Political Prisoners and Deportees.

This is what he did in order to be recognized as a Deported Resistance Fighter.

- On October 13, 1949, Mr. Borycki applied for the status of Deported Resistance Fighter, which was refused and the he was notified of the decision on November 4, 1953. He was, however, granted the status of Political Deportee on November 4, 1953.

- On January 2, 1954, Mr. Borycki filed an appeal. In a request registered with the clerk’s office of the Paris Administrative Court on August 26, 1954, Mr. Borycki asked that the decision of the Minister of Veterans and Victims of War be annulled insofar as it had rejected his request for a card for deported resistance fighters.

- The Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War maintained that Mr. Borycki had been arrested not for acts of resistance but on grounds of his “race”[18].

- Mr. Borycki contested this point and reiterated that he had been arrested for his participation in the resistance, which included distributing anti-German leaflets, putting up posters and carrying supplies, newsletters and weapons.

- In a judgement dated October 25, 1955, the Paris Administrative Court, without even hearing the arguments of each party, dismissed Mr. Borycki’s claim, finding it inadmissible given that he had until July 2, 1954 to contest the decision and that the appeal to the Court was made after that date, i.e., on August 26, 1954.

- On February 2, 1957, Mr. Borycki filed another application for the status of Deported Resistance Fighter, together with some extra evidence. He re-applied on November 25, 1957. All to no avail…

- In a ruling dated January 5, 1961, the Paris Administrative Court (to which Mr. Bory had appealed again[19] in a request registered on April 22, 1958, since his application for a Deported Resistance Fighter card had been implicitly refused, given that had been no further news from the Minister of Veterans and Victims of War) refused Mr. Bory’s request on the grounds that he had previously brought an case before the Administrative Tribunal for the same reason and that in a ruling dated November 25, 1953, which had since become final, his claim had been dismissed.

This was based on the legal concept of res judicata, which the Tribunal cited as a reason for its decision.

- Mr. Bory then filed an appeal with the French Council of State on March 20, 1961 against the judgment dated January 5, 1961, alleging that his 1957 application was based on new documents and that this application should have been admissible according to a law dated December 31, 1957, which had extended the deadline for filing new applications to January 1, 1955.

He also cited a law dated August 1, 1956, which extended the filing deadline to January 1, 1958, and also referred to the preparatory work for the law dated December 31, 1957, and to case law according to which anyone was entitled to file a fresh claim as long as it was accompanied by new evidence. He concluded by saying that the applications he had submitted to the Administrative Court should therefore have been admissible.

- The Council of State once again ruled that his claim was inadmissible and confirmed the Administrative Court’s judgment of January 5, 1953.

- On March 29, 1966, in the context of the General Review of Deported Persons’ Files, Mr. Bory asked the Minister of Veterans and Victims of War to re-examine his case.

- He rightly argued that his request had never been examined on its merits, the various courts having based their rulings solely on the legal details (i.e. that his previous claims had been inadmissible because he had not appealed within the time limit).

In a letter dated August 28, 1968, he provided some further information.

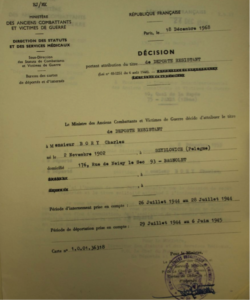

- On July 25, 1968 he was finally granted the status of Deported and Interned Resistance Fighter, as can be seen in the notification of the decision dated December 18, 1968.

On December 24, 1968, after a 19-year struggle, Mr. Bory finally received the notification that he had been granted the status of Deported Resistance fighter.

We note that the Administrative Court and the Council of State never actually examined the merits of the case. They simply deemed that Mr. Bory’s request was inadmissible because he did not appeal within the time limit.

Eventually, in the context of the General Review of Deported Person’s Files, the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War acknowledged his status as a Deported Resistance fighter in July 1968.

Now we turn to the merits of the case:

Numerous documents attest to Mr. Bory’s relentless fight for recognition of his involvement in the Resistance movement. It is worthwhile, then, to look at the grounds on which his commitment to opposing the Germans was not acknowledged.

Mr. Bory was criticized for not having shown the link between his resistance activities and his arrest.

According the French authorities, Mr. Bory was deported on the grounds of his Jewish roots rather than due to his political and resistance activities.

We were concerned by this denial, since Mr. Bory provided numerous testimonies outlining the circumstances of his arrest and his involvement in the French National Front.

- Doctor Rosenfeld, a commander in the French Forces of the Interior testified that he had been arrested on account of his work for the Resistance. And besides, Mr. Bory was not sent straight to Drancy but detained by the Gestapo at their headquarters on Rue Saussaies in Paris, a place that was notorious for holding people opposed the Nazis. Hence Mr. Bory refuted the assertion that he was arrested because he was Jewish.

Statement signed by Dr Rosenfeld, a commander in the French Forces of the Interior

He also provided evidence of his Resistance activities by means of various official documents:

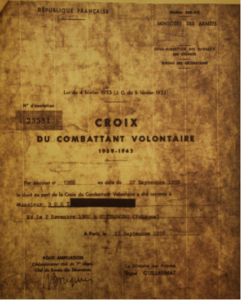

- An R.I.F (French Interior Resistance). membership certificate [20], issued by the Ministry of War,

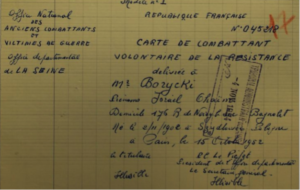

- His volunteer Resistance fighter card, issued on October 15, 1952

Volunteer Resistance fighter card, issued on October 15, 1952

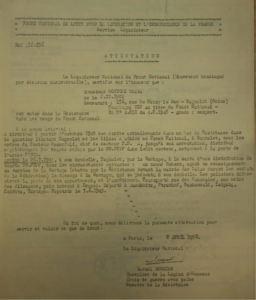

- An attestation from Mr. Mugnier, liquidator of the National Front for the struggle for the liberation and independence of France.

Attestation from Mr Mugnier, of the French National Front

This RIF membership certificate was issued to Chaïm Borycki on April 8, 1958. It states that he belonged to the National Front, a movement that was recognized as being part of the Resistance.

The tasks that he carried out are clearly described: distribution of anti-German leaflets.

He joined the Resistance in October 1940, was arrested on July 26, 1944 and repatriated on June 7, 1945.

He was appointed to the fictitious rank of Sergeant by the Secretary of State for the Armed Forces on August 4, 1948.

He was issued a volunteer resistance fighter card on May 27, 1960.

Another of Mr. Bory’s arguments, last but not least! This point underlines the importance of the medals that were awarded to him after he was refused a “deported member of the Resistance” card.

He was awarded:

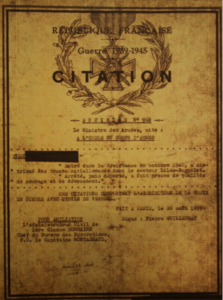

- the War Cross on August 26, 1959, by the French Armed Forces Directorate

War Cross awarded to Mr. Bory on August 26, 1959 by the Armed Forces Directorate and the Minister of War, Pierre Guillaumat (Minister of the Armed Forces from June 1958 to February 1960)

- the Volunteer Servicemen’s Cross on September 22, 1959, also by the Armed Forces Directorate

- Then the Military Medal in the name of the President of the Republic on August 1, 1932

- And lastly, he was appointed Officer of the Legion of Honor

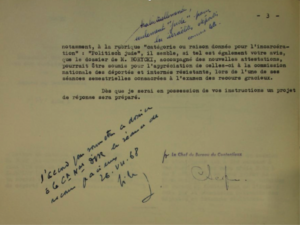

As regards his ex gratia appeal, there is this document from the Head of the Contentious Claims Office of the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs. It clearly states that Mr. Bory was incarcerated as a political prisoner, a political Jewish prisoner, rather than simply as a Jew.

It is clearly stated in this document that Mr. Borycki fell into to the “category” of “politisch jude” rather than that of “jude”, which was used for deported Jews.

Page 4 of the document clearly explains the reasons for awarding him the “deported member of the Resistance” card.

Award of the status of “deported member of the Resistance”

Personal life

Mr. Borycki lost his wife, Rachel, on March 23, 1956.

The declaration of the death of Mrs. Borycki dated March 23, 1956.

In the Bagneux cemetery, we found the communal vault [21] in which Rachel Bory was buried.

The tomb of Rachel Bory, and also who son Roger, who were buried in the Bagneux cemetery

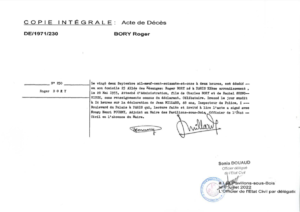

He also lost his only son, Roger Bory, who was 38 years old and worked as an administrator, on September 22, 1971.

Roger Bory’s death certificate

The tomb of his son, Roger Bory, who was buried in the Bagneux cemetery

He got married again, to Semha Sultan, and died on February 25, 1980, at the age of 78.

Charles Bory’s death certicate, issued in 1980

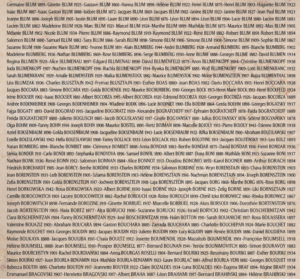

We found his name, Israël Borycki, on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

[1] The National Front is a National Resistance movement founded by the French Communist Party in May 1941. The National Front was active throughout France, but primarily in the northern zone.

[2] After the Liberation, this Robert was shot by the head of the local Resistance network, in front of the town hall in Les Lilas.

[3] Testimonies dated March 23, 1966, requested by Mr. Borycki with a view to having his status as a political deportee revised to that of a deported Resistance fighter. The witnesses lived at 153 and 155 rue Noisy-le-sec in Les Lilas, close to the factory and Mr. Borycki’s home.

[4] Testimony of Mr. Bory (previously Borycki) dated August 28, 1968.

[5] The Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei), a secret police force of the Third Reich, was founded by Hermann Goering and made up of SS officers.

[6] The premises at 11, rue des Saussaies were occupied by the Gestapo in August 1940. This was the Gestapo headquarters. Questioning there was accompanied by beatings, head-first immersion in a bathtub of cold water and thrashings with a dried bull’s penis.

[7] In June 1944, the Forces françaises de l’Intérieur (Interior French Forces) were founded, bringing together the various military units of the Resistance.

[8] Drancy camp: Drancy served as an internment camp and assembly point for the Jews from France before they were sent to concentration camps and killing centers. Nearly 63,000 of them were deported from Drancy.

[9] Convoy 77 was the last of the large transports, carrying 1309 deportees, that left Drancy for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944.

[10] Auschwitz-Birkenau was a large concentration camp and killing center in Poland. More than 1.1 million Jews were murdered there.

[11] Biographies of Georgette Bernard and her two daughters, Denise and Lucienne, written by students of the Galilee High School in Combs-la-Ville in 2020.

[12] Convoy 77 arrived on August 3, 1944, rather than August 2 as stated in the testimony.

[13] Stuttof is just over 20 miles from Danzig (currently Gdansk). The Stutthof concentration camp was the first that the Nazis built outside Germany. It opened on September 2, 1939 and was also, sadly, the last camp to be liberated, on May 10, 1945

[14] Buchenwald was a Nazi concentration camp founded in July 1937 on a hillside at Ettersberg near Weimar, in Germany.

[15] The Leipzig camp was a sub-camp of Buchenwald.

[16] Terezin, also known as Theresienstadt, was a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. As the Nazi other concentration camps were evacuated, Theresienstadt became a convoy destination. Beginning on April 20, 1944, between 13,500 and 15,000 concentration camp prisoners, mostly Jews, arrived at Theresienstadt after being forced to take part in the death marches.

On May 8, Red Army troops liberated the camp and repatriated the survivors to their home countries.

[17] It was not until 1968 that he was finally granted the status of deported resistance fighter.

[18] The status of Political Deportee was attributed to people who were deported on grounds of their “race”. In order to be granted the status of Deported Resistance fighter a link between the arrest and Resistance activities had to be proven. Mr. Bory’s case was far from unusual. Many Jewish resistance fighters had to fight to be granted the title of “deported resistance fighter” because the title was only granted if it was established that the determining cause of the arrest was the resistance activity of the person concerned. As a result, genuine members of the Resistance who were arrested during a round-up, for example, or for any other reason that was not considered to be an act of resistance to the enemy, only qualified for the title of political internee!

[19] Mr. Borycki became Mr. Charles Bory according to the decision of the public prosecutor’s office on April 29, 1959.

[20] R.I.F: Résistance intérieure française, or French Internal Resistance: All the clandestine organizations that fought against the German occupation from June 22, 1940 until the Liberation in 1944.

[21] L’Entraide Fraternelle is a charitable organization, established in 1945, which supports the Brothers of the Grande Loge de France (a masonic order) and their families who find themselves in a precarious or difficult situation. It provides financial assistance to the family in case of death of a Brother.

Français

Français Polski

Polski