Gaston SECNAZI, 1901 – 1944

Gerlys will never dance again; he did not hold onto his life[1]

Danielle Laguillon Hentati

Gaston Secnazi[2]

Auschwitz! Auschwitz! O bloody syllables!

Here we live, here we die a slow death.

We call this slow execution.

Part of our hearts slowly perishes there.

Limits of hunger, limits of strength:

Christ neither knew this terrible path

Nor this interminable and heartbreaking divorce

Of the human soul and the inhuman universe …[3]

“He is there on the stage, the old Gypsy[4]. He is a dancer. A few steps… and suddenly he is transformed. He rediscovers his youth, his suppleness of yesteryear, he leaps and stamps his feet with a youthful vehemence. Guiding his troupe with an unfailing requirement to perpetuate his art and the memory of his people, he sings and dances his joys and suffering. Memories intermingle, he tells of the deportation, the camps, “the forgotten Holocaust[5]” of his people, the memories of his mother, in the only language that he knows, the language of dance.”

Eva[6] was also a dancer and she too recounts the story of the camps and her memories of the deported dancers who faded into anonymity[7].

Gaston Secnazi can no longer dance. His life’s journey ended one day in October 1944 in this “place of no memory”[8].

We have tried to retrace his exceptional career, through military archives kept in Caen[9], through the testimonies of three members of his family: Corinne and Audrey Bacchetta, and Elie Drai[10] and through newspapers, to try to reconstruct, at least in part, his career as an artist.

From Tunis to Paris

Gaston was born in Tunis (Tunisia), into a Tunisian Jewish family (twansa) who lived at 29, rue des Protestants (now rue Ahmed Bayram), between the neighborhoods of the Hara (today’s Hafsia neighborhood) and the Passage, that is to say, at the boundary between the Jewish neighborhood and the new European neighborhood. The family was thus one of those who left the old, dirty and unhealthy Jewish quarter. This represented a slight rise in social status.

View looking towards the rue des Protestants[11]

His father Joseph, born in Tunis in 1869, was the son of Abraham and Zaïra Saada about whom we have no further information. There is no record of their marriage in Tunisia[12]. His father Joseph, born in Tunis in 1869, was the son of Abraham and Zaïra Saada about whom we have no further information. There is no record of their marriage in Tunisia [12]. He had a sister, Esther, who married Menahim-Haï Henry Taïeb; the couple had four daughters: Julie, Emma, Marcelle and Georgette, and lived at 16, avenue de Paris in Tunis, in a beautiful building in the recently constructed European quarter.

His mother, Félicie Driay (registered as Messaouda Drihy at birth), was born in Tunis in 1873. She was the daughter of Joseph, a cobbler who acted as a Rabbi [13], who died on December 21, 1887 at 40, rue Zarkoun in Tunis[14], and Léa Cohen, who “did not speak French; she must therefore have spoken Arabic. In any case, during the few years that Pierre knew his great-grandmother, she spoke the universal language, that of the great-grandmother who made the family happy with her vivacity, her honey cakes and her pastries.[15]”

Joseph, who presumably went to the new Alliance Israélite Universelle [a Paris-based international Jewish organization] school on rue Malta Srira[16], was able to read and write; he then trained to be a tailor and worked as such for the rest of his life. He married Félicie on September 11, 1894 in Tunis.

Félicie et Joseph Secnazi[17]

The couple had three children, all born in Tunis: Albert, born on December 27, 1895, who took his role as the eldest son very seriously, Henry on December 22, 1898, and Gaston, the youngest, on April 7, 1901.

After Gaston was born, the family moved to Paris. We do not know why they left, but it seems likely that one of the reasons was that Félicie’s brothers, Charles and Félix Driay, had already moved to Paris in 1889, two years after their father died. One by one, Félicie’s siblings moved to the French capital to support their mother, Léa, who was by then a widow with two young children: Rachel and Félix.

“Family-based migration was one of the hallmarks of the movement* […]. Not only did immigrants arrive as small families, made up of parents and their children, but they also tended to reassemble, to some extent, the larger family group.[18]”

*of Jews from North Africa to France

In 1909, the Secnazi family was living at 1, rue de Damiette in the 2nd district of Paris[19], as was Félix Driay, Félicie’s brother, an engraver and gilder who would later become a jeweler.

A short time later, the family moved to 39, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin in the 10th district of Paris, where they lived until the beginning of the 1950s.

39 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin

According to various censuses[20], between 15 and 23 families lived in this building, including the Secnazi and Driay families. The family remembered this intimate coexistence[21]. Joseph and Félicie’s three sons were well educated.

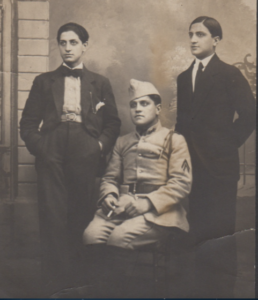

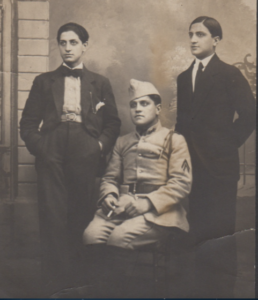

The three brothers, Albert (sitting), Gaston and Henry[22]

Albert served as a private in the infantry in 1914, then in the air corps of the Armée d’Orient (Army of the East). He was demobilized in October 1919[23] and returned to his family home. He was awarded the Victory Medal, the French Commemorative Medal of the Great War, the Interallied Medal, the Medal of the Orient, and the Volunteer Servicemen Cross. He then resumed his printing career, which he probably learned from his maternal uncle, Maurice Driay (Tunis 1875 – Paris 1958), a typographer. In 1922, he married Renée Esther Narboni (Paris 1899 – Draveil 1990), a typist; the couple had one son, Joseph Jacques (Paris 1926 – Arpajon 2001).

As for Henry, he was a commercial traveler; unmarried, he stayed with his parents when he was in Paris. He died suddenly on July 27, 1934 at the railroad station in Dol-de-Bretagne in the Ile-et-Vilaine department[24]. Albert dealt with the all of the paperwork and the funeral.

An artistic child

Presumably, Gaston went to the local elementary school. Was he different from the other children? More sensitive? More introverted? What mysterious twist of fate might have made him take an interest in dance? Did music encourage him to express himself through movement?

Was he influenced by neighbors who were musicians? Some opera and concert artists lived in his apartment building[25]: Victor Pignolet (Reims 1882 – Paris 1953[26]), a composer[27] of works including La Déesse en Folie, an operetta in 3 acts performed at the Excelsior Concert in 1922[28], and of Antoine et son cochon, written in 1930; Eugène Edmond Génin (La Chaux de Fonds, Switzerland, 1871[29]) and Louis Julien Augustin Digoudé, known as Diodet Digoudé,[30] (Constantine, Algeria, 1867 – Paris 1947), a conductor, composer and music publisher.

Digoudé was first mentioned in the 1936 census. By this time, the population of the building had become increasingly cosmopolitan, with the arrival of families from Algeria, Tunisia, Russia, Germany, Greece, Poland and Switzerland.

“Dance is the firstborn of the arts. Music and poetry flow in time; visual arts and architecture shape the environment. But dance exists in both space and time. Before entrusting his emotions to stone, to speech, to sound, man uses his own body to organize space and to give rhythm to time[31].”

Although dance was omnipresent in Tunisian culture, both Muslim and Jewish, it has never been the focus of a comprehensive analysis. Only a few articles have been written, and these about specific periods: antiquity, pre-colonial Tunisia, the beginning of the protectorate, and the contemporary period[32]. From these texts, it emerges that traditional physical activities of a hieratic, religious and mystical nature (including dance), whether professional, military or recreational, were essentially the domain of Muslim men. A physical tradition thus preceded the emergence and establishment of Western physical activities and sports in Tunisia, in particular classical dance, which was taught mainly to Europeans[33], and to girls more than boys. Dance was regarded as too feminine by Tunisian society and was thought to undermine masculine virility.

However, one man dared to dance in the 1920s; an androgynous man dressed as a woman. Ouled Jellaba was stigmatized, excluded and “doubly sanctioned by a conservative society that totally neglected the creative dimension of his shows[34].”

Presumably, the family was unfamiliar with this taste for dance, due to the lack of cultural traditions in Tunisia, and was overly preoccupied with material concerns. But the family was not against it either. The deep affection which bound the members of this family let Gaston’s natural talents to develop and blossom.

Did he study classical dance? There is no evidence to support this. However, in 1925, a commentator wrote: “The young dancer Gaston Gerlys began his career at the Opéra-Comique[35]; he benefited from the late Mariquita’s invaluable instruction, and he remembers it on occasion[36].” This suggests that he had lessons at the Opéra-Comique, where he made his debut.

Marie-Thérèse Gamalery, also known as Madame Mariquita, (Algiers 1838/1840 – Paris 1922) was a Spanish dancer, who was well-known as a choreographer and ballet mistress at the Opéra Comique from 1898 to 1920[37]. Jules Massenet described her as “the most artistic of all the ballet teachers[38].”

Gerlys

A dancer and choreographer[39], Gaston Secnazi performed under the pseudonym of Gaston Gerlys, perhaps in order not to offend family feelings, or to avoid compromising the reputation of a well-known family, but probably also because he wanted a “stage name”.

In 1916, when he was only fifteen years old, Gerlys made a name for himself in ballet[40]. Soon afterwards, he was on the bill in shows in Paris, then fame followed and he was invited to music halls in the provinces. In September 1919 in Marseille, an announcement read “Gaston Gerlys, the most elegant of fellows, an admirable dancer, who has just triumphed at the Folies-Bergère in Paris” would be performing in the “great local show by Antonin Bossy[41].”

The 1920s were known as the Roaring Twenties, a period of intense social, cultural and artistic activity following the horrors of the First World War, which it was said would be the “war to end all wars”. A new generation dreamed of a new world and proclaimed “Never again! They were soon treated to new delights to the sound of music. Having arrived with the Allies, from the United States, jazz made its debut, as did dance, which saw the introduction of pairs dancing (socially, in competition and in shows), radio and sports, against a backdrop of strong economic growth.

This was also the period when music hall replaced café-concerts. People went to the Casino de Paris or the Concert Mayol[42] as they would to the theater: spectators, attractions and songs followed in rapid succession. The sets and the artists’ fanciful costumes were designed by fashionable painters.

It was back in Paris, at the Concert Mayol, that Gaston Gerlys danced in Tout à l’amour![43], and then at the Ambassadeurs in La Revue légère, where he was described as “extraordinary” in the scene “La taxe d’amour”, which he performed with Peggy-Vère[44]. From then on, his name would be linked those of his partners, with whom he danced as a couple.

That same year, a journalist commented: “Gaston Gerlys, the young dancer whose talent we appreciated so much at the last Ambassadeurs show, is hesitating between London and Paris, where prestigious impresarios are vying for him at a high price[45].”

Indeed, in November 1920, Gaston Gerlys began his international career in Brussels: “We are told of the brilliant success of the dancer Gaston Gerlys and his partner Loulou Hegoburu[46] in the new show at the Alhambra[47].”

In April 1921, he had great success at La Gaîté-Rochechouart in Paris in the new show Ça t’étonne! by Saint-Granier and Briquet, two young composers. Géo London’s review was especially positive:

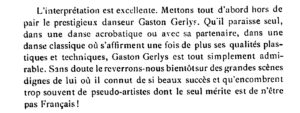

Géo London, ʺÇa t’étonne! by Saint-Granier and Briquetʺ[48]

Then he was in Biarritz during the summer of 1921. He danced with Jeanne Peyroux, known as Mona Païva, his first partnership with a prima ballerina.

In October, the couple performed at the Opéra-Comique in “[…] a ballet by Jean Huré, Au Bois Sacré, that Louise Stichel, who had been appointed ballet mistress, directed with her “inexhaustible imagination”. In a new formula, with backing vocals and narration, Sonia [Pavlova], so expressive as a nymph, was applauded at length, as were Jeanne Peyrouix, known as Mona Païva, and the recently recruited Gaston Gerlys[49].”

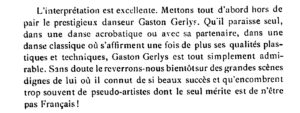

In 1923, when he was appointed principal dancer at the Opéra-Comique, he performed in numerous productions. “Among the stars engaged in the next show En pleine folie, we should mention the name of Mr. Gaston Gerlys, principal dancer at the Opéra-Comique, who will be performing several interesting creations during this show, when he will once again demonstrate his choreographic composition skills and his sound technique, which is so appreciated at the Salle Favart[50].” HIs partner was Lydia Johnson[51] whom Gerlys would encounter in subsequent performances. The critics were full of praise, describing him as a “splendidly alluring” dancer[52], “one of our most marvelous dancers”… “In most scenes, the dancer Gaston Gerlys, on loan from the Opéra-Comique, showed himself to be truly of a very superior class”[53]. Another wrote that he was a “remarkable dancer of grace, strength and suppleness[54].”

In 1924, he performed with another dancer at the Ambassadeurs in the show C’est d’un chic! “Mr. Gaston Gerlys is the perfect partner for Miss Napierkowska, with whom he shared the enthusiastic applause of the public. Supple and bouncy, agile and strong, with an impeccable aesthetic, Mr. Gaston Gerlys dances with a remarkable skill, precision and certainty. His progress is continuous and rapid, and has just been confirmed on the stage at the Ambassadeurs[55].”

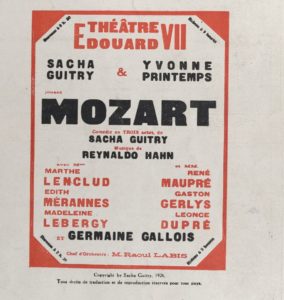

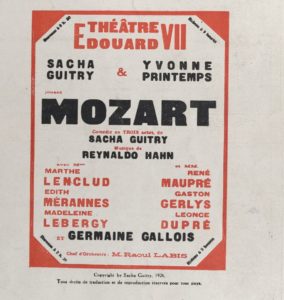

Success opened up new opportunities for Gaston. He was in the cast of the new musical comedy by Sacha Guitry and Reynaldo Hahn, Mozart, which premiered at the Théâtre Edouard VII on December 1, 1925, alongside Sacha Guitry himself and Yvonne Printemps[56].

Poster for Mozart[57]

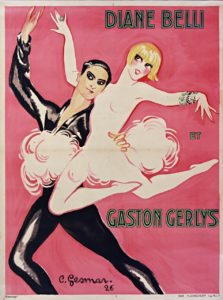

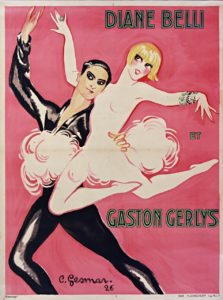

As active as ever, Gaston Gerlys performed with his new partner, Diane Belli.

“But in this new program at the Empire […] the dancers Gaston Gerlys and Diane Belli will no longer appear. Gerlys’ performance is worth noting for his presentation, aesthetics, “nude” costumes, (it is easier to wear a costume than dance “nude”), his work and personal development. Without doubt, numerous roles as a dancer in the Folies-Bergère, Ambassadeurs and Mayol shows, after his brilliant debut at the Opéra-Comique, had enabled Gaston Gerlys to express his choreographic skills, to show us his physique, and to bring out the likeable nervousness that motivates his performance [58].”

Poster featuring Diane Belli and Gaston Gerlys[59]

As a result of his various achievements, Gaston Gerlys went on to build an international career. He started with Germany. “From Munich – We report the huge success in the show at the Deutsches Theater of the charming duo of French dancers Gaston Gerlys and Lysia.”[60], and then he went on to dance in Berlin and Frankfurt. In 1929, he was in Spain, in 1930 in London, in 1931 in Algiers, and then in Buenos-Ayres in Argentina.

“From Buenos Aires – All the Argentinian elite and the French colonial community attended the sensational debut of the dancers Gaston Gerlys and Lysia at the reopening of the Armenonville. The performance of the two renowned artists was a triumphant success.”[61]

Back in Europe in 1932, he was in Scandinavia. Then in 1935, he was back in London. “From London – The French dancers Gaston Gerlys and Lydia, who have just completed a very successful tour of the Paramount theaters, have just signed an important contract for Australia and will embark on the 27th of this month.”[62]

Gaston Gerlys and Lydia[63]

Whenever he was in France, between trips, he continued to dance in various shows. For example, in September 1936: “At the Trianon-music-hall, which every week brings back one or more of our favorite stars, Gaston Gerlys and his exquisite partner, after London and the Americas, made a comeback that was particularly well received. Their performance, in which the finesse rivals the acrobatic audacity and the audacity of the chorographic science, is the kind that the English prefer. We do too.”[64]

His notoriety also led him to lead a glamorous life style: he was seen at the Course des Six Jours[65]; he lent his support to “La Grande nuit des Vedettes” with other artists including Michel Simon, organized by the newspaper “Holahée!” in aid of the Caisse de secours de l’Association générale des étudiants de Paris (Relief Fund of the General Association of Students of Paris) on Friday, May 18, 1934, in the salons Monceau; and again, in the summer, he stayed “With Nine, the famous restaurateur on the Rue Victor-Massé, who runs a hotel in Val d’Esquières, not far from Toulon, for her Parisian regulars.”[67]

These headlines show how interested the columnists were in the man who had devoted his whole life to dance and whose reputation had spread far beyond the French borders.

In November 1939, he appeared in “La Revue des revues” (The Show of shows)[68] with Lydia. This was the last show that was reported in the press. War had broken out by then, and it was no longer a time for celebration.

“When I dance, I cannot judge, I cannot hate, I cannot separate myself from life. I can only be happy and complete. That is why I dance.”[69]

In 1941, Gaston was in Algiers[70]

The reasons for his stay in Algiers are unclear. Was it to perform in a show? Almost certainly. But this raises an important point: why did he not stay there? This seems an obvious question now, because we know the rest of the story. But if we put ourselves in his shoes, it becomes more complicated. Should he stay on in Algiers? Should he leave behind all that made him who he was? The people he loved, the people he had once loved, the streets of Paris, his friends? The reviews, the theaters, the high life between shows, the whole hectic world of the music hall? And lose everything he had? He was not prepared to do that.

There would have been an alternative, however: Tunisia, his native country, but he no longer had any ties there, his parents having burned their bridges after moving to France. Besides, he would no longer have been able to perform there, because by then the dance scene had changed in Tunis, and female dancers were in vogue.

There were also the laws the about status of the Jews, which distinguished them from the rest of the population. Article 9 of the decree relating to the status of the Jews, issued in October 1940, and then article 11 of the decree issued in June 1941, specified that “the present law applies to Algeria, to the colonies, to the protectorate countries and to the territories governed under a mandate”. But Gaston had never been interested in politics and did not feel this applied to him. He was told that in the Free Zone, the rules differed according to a person’s nationality, between the citizens of the countries annexed by the Reich, French citizens and foreigners.

From Algiers, he took the boat to Marseille and then the train to Lyon, which was in the Free Zone and where there was a large Jewish community, including many people born in Tunisia. As was the case everywhere in France, the Jewish community felt well integrated into French society and did not feel it necessary to leave. No doubt Gaston imagined that he would be safe there and that he would find help and support. Somewhat ironically, it was through the very religion from which he had distanced himself that he hoped to escape.

From the limelight into the shadows

In Lyon, he lived at the Hôtel de Bretagne, an old and well-known hotel [71] at 10, rue Dubois in the 2nd district, in good location near the railroad station and not far from Place Belcourt, in an area that was home to many Jewish Tunisian families[72].

Gaston was arrested in Lyon on July 17, 1944 for reasons described as “racial”. It is not known if he was arrested in the street or in the hotel, which was supposed to keep a guest register. He was then imprisoned in Fort Montluc. No records were kept other than a simple note on a scrap of paper[73].

A few days later, he was transferred to Drancy camp, where he arrived on July 24, 1944, and was interned under the serial number 25745. According to the search logbook N° 157[74], he had 1875 French francs in his possession. The refined, sensitive dancer, who had led “a life rich in pleasure”, was suddenly faced with appalling conditions: overcrowding, inadequate hygiene, hunger and thirst. How might he have felt?

On July 31, 1944, Gaston boarded the last large convoy of Jews from Drancy to Auschwitz. In France, as elsewhere, the cooperation of the railroad companies was essential in carrying out the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question in Europe”.[75]

Map of the railroad network in Europe [76]

For the four long days and three long nights that the locked cattle cars rolled along, there was no air, no light, no food and very little water. In the suffocating heat, the stench became foul. How did Gaston try to escape this unbreathable atmosphere? Did he see images of his past life flash before his eyes? Did he hear the music of the ballets and shows? Was he aware that his elderly parents had been spared? Did he imagine that in Germany, such a cultured country, the Germany of philosophy and music, the Germany that had welcomed him and applauded him so much, there had been “a breakdown of civilization”[77]? Probably not.

On August 3, 1944, finally, the train screeched to a halt. He heard the clatter of the doors opening and the clamor of people pouring off the train. He had arrived. As he was still young and healthy, he was put in the line of people who were able to work. The dehumanization process began immediately, one step after another: The process of dehumanization began immediately, one step at a time: the few possessions and personal belongings he had were taken from him, he had to strip naked, he was shaved, he was tattooed on his left arm with the number B 3920 and he was given clothes that were too big or too small because they had been taken from people who had been killed. All this so that there was nothing left of his “former life”. Then he was taken to the barracks where he met up with two cousins on his mother’s side: Victor and Jacques Driay[78].

Along with his cousins, he was assigned to Kommando Petersen Kanalisation to dig trenches outside the camp. Like all the others, Gaston worked in extremely difficult conditions, from daybreak, after the morning roll call in the camp courtyard. The work was grueling, and those who stopped were beaten, sometimes to death. Lunch was just a thin soup.

By mid-September, Gaston was in very bad shape. In spite of “a strong and willing character”, he could not withstand the appalling living conditions. He felt crushed by the brutality and inhumanity and was overwhelmed with fear. Desperate in the face of a situation that will forever be beyond comprehension, he could hold out no longer.

“I give no thought now to posterity,,

That divine ardor, is long gone from me,

And the Muses, like strangers, now are fled.”[79]

One evening, he was selected to be sent to the gas chambers. “On the evening of October 2, a roll call took place, without warning. All the convicts were made to stand naked in front of an officer, who noted down the numbers of those who were to be gassed. […] Gaston’s number was taken […]”[80]

Roll-call 1941/1942, by Wincenty Gawron[81]

Gaston was taken, together with the other “selected” people, to Birkenau. “Two days later, 800 Jews went to the crematorium. Gaston was one of them.”

As a “former comrade in captivity”, Victor Driay testified after the war:

“I could see all the external signs that were associated with the exterminations, such as: smoke and flames coming out of the crematorium ovens, the smell of burnt flesh that spread over a great distance, the prisoners’ clothing returning to the camp.”[82]

The endless pain

Apparently, his parents and his brother Albert started looking for Gaston very early on; in fact, as early as October 12, 1944, Le Directeur des Services Fichiers et Statistiques du Ministère des Prisonniers, Déportés et Réfugiés (the Director of the Files and Statistics Department of the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees) shows that, according to his archives, Gaston was arrested in Lyon and interned at the Drancy camp from July 24, 1944 to July 31, 1944, the date on which he was deported.

After the war, Victor and Jacques Driay, who survived, notified Gaston’s family. How could they describe the “unspeakable”? What words might they have used? What did they say and what did they keep quiet about?

Courageously, Joseph Secnazi carried out the formalities necessary to procure the standard certificate ʺMʺ, n°18.083, which was issued on March 21, 1946.

Further to Victor Driay’s statement: “In view of the above facts, I can therefore certify under oath that my cousin, who has been reported missing to this day, died in the circumstances that I have described.”[83], Gaston’s death certificate was issued on January 7, 1947 and then entered into the civil registers of the 10th district of Paris on November 10, 1947. At the request of his father, the phrase “Died for France” was added to the death certificate on January 13, 1948.

In April 1951, a certificate “for the application of exemption of inheritance tax on death for beneficiaries of estates of war victims according to articles 10 and 12 of the law of December 31, 1939” with the phrase “Cause of death: Extermination in a DEPORTATION camp”, was issued to the family.

Félicie did not live to see the outcome of the case. She was devastated by the death of her son, which occurred in circumstances that she did not understand, but about which she feared the worst. Given that there was no grave, she was unable to go and pay her respects, or to mourn little by little. She died on February 10, 1950.

Joseph was overwhelmed, crushed by pain in the wake of death after another. Neither the formalities he undertook to have his son’s death registered and the appropriate words added to the death certificate, nor the recognition that followed, could make up for the loss he felt. The emptiness became more and more profound and he died on February 7, 1953.

It was therefore Albert who took over the dossier. In November 1953, he applied for the title of “political deportee” for his brother Gaston, which was granted on December 19, 1955, putting an end to eleven years of administrative procedures. All that remained was the memory of a beloved brother who had died in such tragic circumstances.

[1] This title comes from the stories of former deportees. When one of their number was ill, they would say to him “Hold on to your life”

[2] Portrait published on the Yad Vashem website: https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr&s_id=&s_lastName=SECNAZI&s_firstName=&s_place=&s_dateOfBirth=&cluster=true

[3] Aragon (François la Colère), « Musée Grévin », 16 October 1943. S.n. (Les éditions de minuit & La Bibliothèque Française), s.n. (Paris & Saint-Flour) s.d. (1943).

[4]Show entitled ʺMémoires d’un vieux tziganeʺ, review by Nicole Bourbon : https://www.regarts.org/Danse/memoires-dun-vieux-tzigane.htm

[5] Expression of Sabine Forero Mendoza, ʺ « Et nous, nous sommes les porteurs. » Ceija Stojka et la mémoire du génocide tsiganeʺ, in Presses Universitaires de France, Ethnologie française, XLVIII, 2018/4, p. 699-706.

[6] This was Eva Fahidi (born in 1925 in Hungary), a Hungarian writer and Auschwitz survivor. Noémie Halioua, ʺÀ 90 ans, une rescapée d’Auschwitz danse pour témoignerʺ : https://www.lefigaro.fr/culture/2016/01/25/03004-20160125ARTFIG00234–90-ans-une-rescapee-d-auschwitz-danse-pour-temoigner.php

[7] No research has been done on deported female dancers. Only two names have been recorded for posterity: Franciszka Mann (1917-1943) and Maria Rubinstein (1914-1942), who was avenged by her twin brother, Sylvin Rubinstein (1914-2011), “a flamenco dancer who disguised himself as a woman to kill Nazis.”

[8] Reference to the work of Jacques Hassoun, Non Lieu de la Mémoire. La cassure d’Auschwitz, Paris, Bibliophane, 1990.

[9]Dossier SECNAZI Gaston DAVCC 21 P 537 750.

[10] I thank them most sincerely.

[11] Alfa Souika’s private collection

[12] Rabbi Moché Uzan carried out research in the archives of the Jewish community of Tunisia. I would like to take this opportunity to thank him warmly. It should also be noted that the surname SECNAZI has several spellings in Algeria and Tunisia: Eskenazi / Skenadji / Seknagi / Esquinazi / Askinazi, which further complicates the research.

[13] Elie Drai, La déportation de la famille Driay, p. 10. https://fr.calameo.com/books/005017555e32fcda840a8

[14] Death certificate kindly provided by Moché Uzan, Rabbi in Tunis.

[15] Elie Drai, La déportation de la famille Driay, p. 10.

[16] Jean-Claude Kuperminc, ʺLe regard des premiers instituteurs de l’Alliance israélite sur les Juifs de Tunisieʺ, in Cohen-Tannoudji Denis, Entre Orient et Occident. Juifs et Musulmans en Tunisie, Éditions de l’Éclat, Collection Bibliothèque des fondations, 2007, p. 347-356.

[17] Corinne Bacchetta’s private collection.

[18] Doris Bensimon-Donath, L’Intégration des Juifs nord-africains en France. Nice : Institut d’études et de recherches interethniques et interculturelles, 1971, (p. 3-263), p. 40.

[19] Archives of the 10th district of Paris, marriage certificate dated August 14,1909 : Joseph was a witness to the marriage of his sister-in-law ,Rachel Driay, and David Berrebi.

[20] Archives of the 10th district of Paris, 1926, 1931 and 1936 censuses. It should be noted that censuses did not begin in Paris until 1926, in contrast to other French municipalities.

[21] Corinne Bacchetta, oral testimonial on April 26, 2021.

[22] Corinne Bacchetta’s private collection

[23] SECNAZI Albert, Archives of Paris, file registration number 734

[24] L’Ouest-Éclair (Rennes) – 1934/07/29 (Number 13779), p. 11.

[25] Archives of the 10th district of Paris, quartier Porte Saint-Martin, 1926 census, ref 239/661 and 240/661. Archives of the 10th district of Paris, Porte Saint-Martin quarter, 1931 census, ref 219/629 et 220/629. Archives of the 10th district of Paris, Porte Saint-Martin quarter, 1936 census, ref 219/314.

[26] Marne departmental archives, class 1902, file registration number 1148; Archives of the 16th district of Paris, death certificate n°165.

[27] BNF Data: https://data.bnf.fr/fr/16568717/victor_pignolet/

[28] https://www.artlyriquefr.fr/dicos/Cinquante%20ans%20-%20operette.html

[29] Doubs departmental archives, Besançon division, class 1891 file registration number 1033

[30] Jean-Claude Gosselin’s family tree: https://gw.geneanet.org/sjc0328?n=digoude&oc=&p=louis+julien+augustin

[31] Curt Sachs, Introduction to l’Histoire de la danse, Gallimard, 1938, p. 7.

[32] Bertholon Dr., ʺEssai sur la religion des Libyensʺ, Revue Tunisienne, 1909, T. XVI. Erraïs Borhane, Ben Larbi Mohamed. ʺEthnographie des pratiques corporelles dans la Tunisie précolonialeʺ, Cahiers de la Méditerranée, Numéro thématique Les Maghrébins et la culture du corps, n°32, 1, 1986, p. 3-24. Étienne Deyrolle, ʺLes Danseurs Tunisiensʺ, in Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris, VI° Série. Tome 2, 1911, p. 262-267. Maud Nicolas, ʺDu divertissement au loisir à Tunis : le cas de la danseʺ, in Anna Madœuf, Robert Beck, Divertissements et loisirs dans les sociétés urbaines à l’époque moderne et contemporaine. Actes du colloque Divertissements et loisirs dans les sociétés urbaines, une approche comparative monde occidental-monde musulman, Université François-Rabelais de Tours, 15-17 mai 2003, Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2005, p. 133-144.

[33] Among the teachers, we can cite Eugénie Antoinette Staats (Paris 1875 – Tunis 1939), mistress of the Ballet Corps at the National Opera in Paris, then at the Municipal Theater of Tunis. She was also a professor of dance and physical arts at the École Normale and the École Paul Cambon. Her teaching earned her the Palmes académiques (1929). She was the sister of the famous dancer Léo Staats (1877-1952) who was Ballet Master of the Paris Opera. (1908-1928). Source: Danielle Laguillon Hentati, Les Palmes académiques en Tunisie (1881-1956) – work in progress.

[34] Rim Benrjeb, ʺOuled Jellaba, une métamorphose d’un corps sexuéʺ : http://www.misk.art/lire/ouled-jellaba-une-m%C3%A9tamorphose-d%E2%80%99un-corps-sexu%C3%A9

[35] The main roles he created: GERLYS crée Polyphème (Dieu Pan), Au Beau Jardin de France (Vertumnus), Au Bois sacré (le Satyre).

[36] Le Petit Journal, 25 juillet 1925, p. 4.

[37] https://www.artlyriquefr.fr/dicos/Danse%20Opera-Comique.html

[38] Thierry Malandain and Hélène Marquié, “Dans les pas de Mariquita”, Recherches en danse [Online], 3 | 2015, Online since 19 January 2015, connection on 06 June 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/danse/922; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/danse.922

[39] Dossier SECNAZI Gaston ; Yad Vashem : https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr&s_id=&s_lastName=SECNAZI&s_firstName=Gaston&s_place=&s_dateOfBirth=&cluster=true

[40] Corinne Bacchetta, oral testimonial of April 26, 2021.

[41] Le Petit Marseillais, 7 septembre 1919, p. 3.

[42] the Concert-Parisien, which became the Concert Mayol in 1909, was then on rue de L’Échiquier (Paris 10th district), near to the family home.

[43] L’Homme libre (Paris. 1913) – 1920/01/09 (Year 8, N°1267)

[44] La Rampe July 11, 1920, p. 14. – Peggy Vere was a British music hall performer, dancer and singer, as well as a comedienne and film actress. She performed in France from 1913 to 1940.

[45] Les Potins de Paris, July 15, 1920 (Paris. 1918) – 1920/07/15 (Year 4, N°172), p. 16.

[46] Marie-Louise Hégoburu (Bordeaux 1898 – La Celle-Saint-Cloud 1947) was a French music hall artist, dancer, showgirl, singer and film actress.

[47] Le Figaro, November 10, 1920, p. 5.

[48] Extract from: Géo London, ʺÇa t’étonne ! de Saint-Granier et Briquetʺ, L’œuvre, 1er avril 1921, p. 4.

[49] Journal d’information du Centre chorégraphique national de Nouvelle-Aquitaine en Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Malandain Ballet Biarritz, Numéro 82, avril/juin 2019, p. 19.

[50] Le Figaro, March 3, 1923, p. 4.

[51] Lydia Johnson (Rostov, Russia, 1896 – Naples, Italy, 1969) was a Russian dancer and actress. After studying classical dance at the dance school of A. Nelidov, she made her debut at the Mamontov Theater in Moscow where she was the partner of the English dancer Albert Johnson; the couple married and had a daughter who would have a career as an actress in Italy under the name of Lucie d’Albret. After the October Revolution, Lydia took refuge in Italy; she had a long career in France and Italy. Source: http://www.russinintalia.it/dettaglio.php?id=812

[52] Louis Lemarchand, ʺCe qu’est une « super-revue »ʺ, in Le Journal, March 10 ,1923, p. 4.

[53] G. de Pawlowski, ʺPremière aux Folies-Bergère “En pleine folie”, in Le Journal, March 11, 1923, p. 5.

[54] La République française, March 26, 1923, p. 4.

[55] Le Figaro, June 3, 1924, p. 3. – Stacia Napierkowska (Paris 1891 – 1945) was a French dancer of Polish origin, and actress with a very long film career.

[56] Yvonne Printemps (Ermont-Eaubonne 1894 – Neuilly-sur-Seine 1977) was a French lyric soprano and dramatic actress who enjoyed great success in the inter-war period.

[57] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90109740?rk=21459;2

[58] La Presse, March 28,1926, numéro 4060, p.2

[59] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90109740.item

[60] Le Journal, May 15,1928, p. 4.

[61] Le Journal, November 17, 1931, p. 6.

[62] Le Journal, February 19, 1935, p. 7.

[63] Shot taken from a very short film: https://youtu.be/OV_OVKVPo5Q?t=163. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Corinne Bacchetta, who sent me the link, as well as Sönke Fenzl and Rim Fenzl Hentati who helped me with these pictures.

[64] Chronicle ʺMusic-halls et Cabaretsʺ, signed by Marc Blanquet, ʺMireille at the Alhambra; the Empire program; “Atout…au coucou” at Le Coucou; Gerlysʺ comeback, Le Journal, September 27, 1936, p. 8.

[65] Paris-Soir, April 8, 1932, p. 4. – Les courses de six jours, or the he Six Day Races (abbreviated as the Six Jours/Six Days for any given host city) were track cycling competitions with a program of cycling events and entertainment.

[66] Le Jour, May 13, 1934, p. 7.

[67] Chanteclerc, October 25, 1934, p. 3.

[68] Paris-Soir, November 29, 1939, p. 2.

[69] Lyrics by Hans Bos, dancer: https://balletmanilaarchives.com/home/2020/2/17/3mmf4j2c31i0m0yytvpi3tr2bivg3f

[70] Corinne Bacchetta, oral testimonial on April 26, 2021.

[71] Contacted by phone on July 19, 2021, the receptionist told us that this hotel had been in business continuously for 200 years.

[72] « Le voyage sans retour d’Abraham Albert Boucara », http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/abraham-boucara/; « La vie brisée de Laure Cohen », http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/laure-cohen-nee-taieb/; ʺEn mémoire de Dario Boccaraʺ, http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/dario-boccara/; ʺLa vie inachevée d’Élie Gaston Setbonʺ, https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/elie-setbon/.

[73] https://archives.rhone.fr/ark:/28729/cqh9183zt0n6/fe1ca081-026d-40eb-a981-e2afa2fd3168

[74]https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=identifiant_origine%3A%28FRMEMSH0408707130635%29

[75] Jochen Guckes, Le rôle des chemins de fer dans la déportation des Juifs de France, Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, « Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah », 1999/1 N°165, p. 29-110.

[76] Source : https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/fr/map/european-rail-system-1939?parent=fr%2F5789

[77] Expression used by Jacques Hassoun, Non Lieu de la Mémoire. La cassure d’Auschwitz, op. cit.

[78] Statement by Jacques Driay dated February 28 ,1946, Dossier SECNAZI Gaston.

[79] Joachim du Bellay, ʺLas, où est maintenant ce mépris de Fortuneʺ, Les regrets, (1558).

[80] Elie Drai, La déportation de la famille Driay, p. 30.

[81] L’appel (Roll-call 1941/1942) de Wincenty Gawron (1908-1991). Oil painting, plywood, 87 x 105 cm, USA 1964. Collections of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. https://historycollection.com/50-haunting-paintings-drawings-prisoners-auschwitz/2/

[82] Witness statement of Victor Driay dated March 31, 1946, Dossier SECNAZI Gaston.

[83] Witness statement of Victor Driay dated March 31, 1946, Dossier SECNAZI Gaston

_____________________

غاستون سكنازي 1901-1944

جرليس لن يرقص أبدا، لم يمسك بحياته [1]

دانيال لاغيون هنتاتي

غاستون سكنازي[2]

أوشفيتز أوشفيتز أيتها الألفاظ الدموية

هنا نعيش، هنا نموت على نار هادئة.

نسمي ذلك التصفية البطيئة

جزء من قلوبنا يموت شيئا فشيئا

حدود الجوع، حدود القوة :

فلا المسيح عرف هذه الطريق الفظيعة

ولا هذا الطلاق اللانهائي والممزق

للروح الإنسانية مع عالم لا إنساني…[3]

هو هنا على الخشبة، الغجري العجوز[4]. . هو راقص. خطوات قليلة… وسريعا ما يتغير. يستعيد شبابه، مرونته القديمة، يقفز، يضرب بالأرجل بعنف طفولي. قائدا لفرقته وفق متطلبات لا هوادة فيها لتخليد فنه وذاكرة شعبه، يُغني ويرقص بأفراحه وآلامه. الذكريات تتشابك، يحكي الترحيل، المعسكرات، “الهولوكست المنسي [5] ” لشعبه، ذكرى والدته : من خلال اللغة الوحيدة التي يعرفها، لغة الرقص.

إيفا[6] أيضا ترقص، تحكي عن المعسكرات، تروي ذاكرة الراقصين المرحّلين ومن سقطوا في النسيان.[7].

غاستون سكنازي لم يعد قادرا على الرقص. انتهى مسار حياته ذات يوم في أكتوبر 1944. في هذا “اللامكان من الذاكرة”.[8].

حاولنا رسم مساره الاستثنائي بفضل الأرشيفات العسكرية، لأن ملفه كان محفوظا في مدينة كاين، [9]، وأيضا بفضل شهادات ثلاثة أفراد من عائلة كورين وأودري باشيتا وإيلي دراي[10] ، وبفضل الجرائد لإعادة تركيب مساره الفني، ولو جزئيا على الأقل.

من تونس إلى باريس

ولد غاستون في العاصمة التونسية، في عائلة تونسية يهودية (توانسة)، كانت تعيش برقم 29 زنقة البروتستانت (تسمى اليوم زنقة أحمد بيرم) بين أحياء الحارة (اليوم حي حفصية) والممر، أي في الحدود بين الحي اليهودي والحي الجديد الأوربي. تعتبر العائلة إذن من جملة الذين غادروا الحي القديم اليهودي المتسخ وغير النظيف، وهي علامة على ارتقاء اجتماعي محتشم.

نحو زنقة البروتستانت[11]

ازداد والده جوزيف في 1869 بتونس وهو ابن أبراهام وزائرة سعادة اللذين لا نملك معلومات عنهما. لم نجد أثرا لوثيقة زواجهما بتونس. له أخت، إستير، تزوجت ميناحيم خاي هنري الطيب. ازدادت في بيت الزوجين أربع فتيات : جولي، إيما، مارسيل وجورجيت. كانت العائلة تعيش برقم 16 شارع باريس بتونس، في عمارة جميلة بالحي الحديث الأوربي.

ولدت أمها فيليسي درياي (التي تم التصريح بها باسم مسعودة دريهي عند ولادتها) سنة 1873 بتونس. فهي ابنة جوزيف، مهنته إسكافي، كان يمارس وظائف حاخامية،[13] ، توفي يوم 21 دجنبر 1887 برقم 40 زنقة زرقون بتونس[14]، ولياّ كوهين التي “لا تتكلم الفرنسية”، فكانت بلا شك تتكلم العربية. وكيفما كان الحال، خلال بضع سنوات التي عرف خلالها بيار أمّ جدته، كانت هذه الأخيرة تتكلم اللغة العالمية، وهي لغة الجدة التي كانت تخلق السعادة في العائلة بحيويتها، وحلوياتها المحضّرة بالعسل والمعجّنات.[15] »

ذهب جوزيف بلا شك إلى المدرسة الجديدة التابعة للرابطة الإسرائيلية العالمية بزنقة مالطا الصغيرة. [16]. كان يعرف القراءة والكتابة ثم تعلّم مهنة خياط التي مارسها طوال حياته. تزوج فيليسي يوم 11 شتنبر 1894 بتونس.

فيليسي وجوزيف سكنازي[17]

سيولد للزوجين ثلاثة أطفال، ازدادوا جميعهم بتونس : ألبير في 27 دجنبر 1895 والذي سيأخذ مكانته، ككبير العائلة، على محمل الجد، ثم هنري في 22 دجنبر 1898 وغاستون في سابع أبريل 1901 وهو الأصغر.

بعد ولادة غاستون، استقرت العائلة في باريس حيث التحقتْ بعائلة درياي. أما أسباب هذه الهجرة فهي غير معروفة لنا. ولكن يمكن أن نفترض بأن استقرار شقيقيْ فيليسي، شارل وفليكس درياي، عام 1889 في باريس، أي بعد سنتين على وفاة الأب، قد لعب دورا في هذا الشأن. وشيئا فشيئا، استعاد الشقيقان بناء نفسيهما في العاصمة الفرنسية، حول أمهما لياّ، التي أصبحت أرملة، صحبة طفليها الصغيرين : راشيل وفليكس.

“الهجرة العائلية هي إحدى خصائص الحركة (…) ليس فقط أن المهاجرين يصلون بعائلات محدودة، مكّونة من الآباء وأطفالهم، ولكن أكثر من ذلك يحاولون، ولو في حد معين، إعادة تشكيل المجموعة العائلية في مفهومها الواسع”.[18]

في 1909، كانت عائلة سكنازي تعيش برقم 1 زنقة دامييت في باريس2 [19] وكذلك فليكس درياي، أخ فيليسي، نحاث ومطلي، والذي سيصبح فيما بعد، مجوهراتيا.

أياما قليلة بعد ذلك انتقلت العائلة إلى الرقم 39 زنقة فوبور سان-مارتان في باريس العاشرة حيث ستعيش طويلا إلى بداية سنوات الخمسينيات.

39 زنقة فوبور سان-مارتان

حسب الإحصائيات المختلفة التي تمّ الاطلاع عليها[20]، فبين 15 و23 عائلة قطنتْ في هذه العمارة من بينها سكنازي ودرياي. بقي هذا التعايش الوثيق حاضرا في الذاكرة العائلية[21] . أبناء جوزيف وفيليسي الثلاثة استفادوا من تربية جيدة.

الأشقاء : ألبير (جالس) ثم غاستون وهنري[22]

بعدما جُند ألبير في 1914، في سلاح المدفعية، وبعده في طيران جيش الشرق، بصفته جنديا من الدرجة الثانية تمّ تسريحه من الخدمة في أكتوبر 1919 [23] . رجع إلى المنزل العائلي، مغطّى بالأوسمة : ميدالية النصر، الميدالية التذكارية الفرنسية للحرب الكبرى، ميدالية الدول الحليفة، ميدالية الشرق، صليب المحارب المتطوع. عاد إلى عمله كمطبعي، والذي تعلّمه، بلا شك، قرب خاله، موريس درياي (تونس 1875- باريس 1958) تيبوغرافي. وفي 1922 تزوج روني إستير ناربوني (باريس 1899-درافيل 1990)، ضاربة على الآلة الكاتبة، وسيزداد عند الزوجين ولدهما، جوزيف جاك (باريس 1926- أرباجون 2001).

أما هنري فهو متجول تجاري يسافر من أجل عمله وغير متزوج. يعيش مع والديه حينما يكون في باريس. وقد توفي فجأة يوم 27 يوليوز 1934 بمحطة القطار في مدينة دولْ بإقليم بروطاني [24] الفرنسية. تكلّف ألبير بإجراءات الدفن.

الابن الفنان

على ما يظهر فغاستون ذهب إلى المدرسة الابتدائية بالحي الذي سكن فيه. هل كان مختلفا عن الأطفال الآخرين ؟ أكثر منهم إحساسا ؟ أكثر انطواء ؟ ما الأهداف السرية التي جعلته يهتمّ بالرقص في مساره ؟ هلْ بالموسيقى التي حفّزته على المبادرة بالتعبير ؟

هل تأثر بجيران موسيقيين ؟ في العمارة التي قطن بها سكن أيضا فنانون مغنيون [25] : فكتور بنيولي (غانس 1882- باريس 1953[26])، ملحن [27] وخاصة لأوبيريت “إلهة في الجنون” المكوّنة من ثلاثة مشاهد، والتي أُعدت من طرف إكسيلسيور كونسير في 1922 [28][29]1922 أو “أنطوان وخنزيره” المهيأة في 1930، أوجين إدموند جنين (لا شو دو فون، سويسرا، 1871)، لويس جوليان أوغستان ديغودي المعروف بديودي ديغودي[30] (قسطنطينة الجزائر 1867- باريس 1947) رئيس جوق، ، ملحن، وناشر موسيقي.

هذا الأخير ظهر في إحصاء 1936، حين أصبحت الساكنة أكثر فأكثر كوسمبوليتية، وذلك بمجيء عائلات من الجزائر وتونس وروسيا وألمانيا واليونان وبولونيا وسويسرا.

“الرقص هو الوليد الأول في الفن. الموسيقى والشعر يمضيان مع الزمن، الفنون التشكيلية والهندسة المعمارية تشكلان الفضاء. لكن الرقص يعيش، في نفس الوقت، في الفضاء وفي الزمن. قبل تسليم مشاعره إلى الحجارة، الفعل، الصوت، يستعمل الإنسان جسده الخاص لينظم الفضاء وإحداث إيقاع للوقت.[31]

إذا كان الرقص حاضرا بقوة في الثقافة التونسية الإسلامية كما اليهودية، فهو لم يكن موضوع أي دراسة عامة، بل فقط مقالات قليلة همّت فترات محددة : الجاهلية، تونس قبل الاحتلال، بداية الحماية والحقبة المعاصرة[32]يتبيّن من هذه الكتابات بأن الأنشطة الجسدية التقليدية، ذات الطابع الكهنوتي والديني والصوفي (بما فيها الرقص) والمهني أوالعسكري أو التي لها وظيفة خلق المرح، إنما تهم خاصة الرجال المسلمين. هي ثقافة جسدية تقليدية كانت توجد إذن قبل ذلك، حين ظهور الأنشطة الجسدية الرياضية الغربية في تونس وخاصة الرقص الكلاسيكي والذي اهتم الأوروبيون كثيرا بتعلمه. والبنات تعلّمنه أكثر من الأولاد. ذلك أن الرقص اعتبر أكثر نسوية في المجتمع التونسي وأنه يمس بالقدرة الرجولية.

ومع ذلك، فإن رجلا تجرأ على الرقص في العشرينيات، مخنث ومتشبه بالنساء. ولْد جلاّبة وُجهت إليه الأصابع ونُفي، “عوقب مرتين في مجتمع محافظ لا يبالي نهائيا بالبعد الخلاق لهذه العروض.[34]

ومن المحتمل أن الوسط العائلي كان غريبا عن هذا الميل للرقص، وذلك لعدم وجود تقاليد ثقافية في تونس، لأنه وسطُ منشغل بالحاجيات المادية. ولكنه لم يكن أيضا ليعارض. فقد مكّنت العلاقة العميقة التي تربط بين أفراد العائلة من تطوير المؤهلات الطبيعية لغاستون، وتفتّق موهبته.

فهل درس الرقص الكلاسيكي ؟ لا شيء يسمح بتأكيد ذلك. لكن في 1925 كتب أحد المعلقين : “بدأ الراقص الشاب غاستون جيرليس مسيرته المهنية في الأوبرا الكوميدية. [35] . حصل على تعليم جيد من قبل المأسوف عليها ماريكينا، ويتذكر ذلك في كل مشاريعه، [36] ، وهو ما يعني بأنه تابع دروسا في الأوبرا الكوميدية أو أنه درس بها.

ماري تيريز جيماليري المدعوة السيدة ماريكيتا (الجزائر 1838/1840- باريس 1922) كانت راقصة إسبانية ظلتْ مشهورة ككوريغراف ومعلمة باليه من 1898 إلى 1920 [37] في الأوبرا الكوميدية. اعتبرها جول ماسيني “أكبر فنانة من بين جميع معلمات الباليه”.[38]

جيرليس

راقص، فنان كوريغرافي[39]، غاستون سكنازي مارس فنّه تحت لقب غاستون جرليس، ربما حتى لا يصدم بعض الحساسيات العائلية، وحتى لا يخالف ما يتّصل بشرف عائلته المعروفة، وكذلك غالبا ليتحصّل على اسم شهرة.

في 1916، حين كان سنه فقط خمسة عشر عاما، أثار جيرليس الانتباه في عدة حفلات باليه[40].. وسرعان ما أصبح في أغلفة بعض المجلات في باريس، ثم جاءت الشهرة ودُعي لوصلات في مسرح المنوعات في بعض الأقاليم. وفي 1919 تم الإعلان بمارسيليا عن مشاركة “غاستون جرليس، الأكثر أناقة من بين رفاقه، راقص مرموق، تألّق حديثا في مسرح فولي بيرجير في باريس” في “العرض المحلي الكبير لأنطونان بوسي”.[41] »

سنوات العشرينيات التي اعتبرت السنوات المجنونة، هي الفترة التي عرفت نشاطا ثقافيا وفنيا مكثفا كرد فعل على فظائع الحرب العالمية الأولى، والتي اعتقد البعض بأنها ستكون “آخر الآخرات”. يحلم الجيل الجديد بعالم جديد وينادي “لا هذا أبدا”. نستعجل لنقترح عليه نشوة جديدة على وقع الموسيقى. وظهر الجاز قادما من الولايات المتحدة مع الحلفاء، وكذلك الرقص الذي أدخل الرقص الثنائي (الاجتماعي، والمنافسة أو الفرجة) ، ثم الراديو ومختلف الرياضات في إطار وتيرة اقتصادية متصاعدة.

في هذه الفترة أيضا عوّض مسرح المنوعات بصفة نهائية مقهى الحفلات. أصبح الناس يذهبون إلى كازينو باريس أو إلى كونسير مايول مثلما يذهبون إلى المسرح : المتفرجون، الألعاب والأغاني تتتابع بإيقاع سريع. الديكورات والملابس الغريبة للفنانين مصممة من قبل رسامين ذوي شهرة.

وفي كونسير مايول بعد عودته من باريس، رقص غاستون جرليس في “كل شيء للحب”، [43]ثم في مسرح السفراء في العرض الخفيف والذي وُصف فيه بأنه “عجيب” في مشهد “ضريبة الحب” التي لعب فيها إلى جانب بيغي-فير.[44]

هكذا فصاعدا أصبح اسمه مقرونا بأسماء شركائه الذين كان يرقص معهم ثنائيا. وفي هذه السنة كتب أحد الصحفيين “غاستون جرليس، الراقص الشاب الذي أعجبنا كثيرا بنبوغه في العرض الأخير بمسرح السفراء ظل يتردد بين لندن وباريس حيث كان يتهافت حوله وكلاء أعمال متألقون اقترحوا عليه مبالغ خيالية “.[45]

وفعلا، في نونبر 1920، بدأ غاستون جرليس مسارا دوليا في بروكسيل : “سمعنا بالنجاح الباهر الذي حقّقه الراقص غاستون جرليس وشريكته لولو هيغوبور [46]هيغوبور في العرض الأخير بمسرح الحمراء”.[47]

وفي أبريل 1921، حصل على تفوق ملحوظ في قاعة الموسيقى غايتي روشوشوار في باريس في العرض الأخير “هل هذا يدهشك ” لراقصين شابين : سان غرانيي وبريكي. فالتغطية التي أنجزها جيُو لندنْ كانت كثيرة المدح في حقه.

جيُو لندنْ : “هل هذا يدهشك” لسان غرانيي وبريكي[48]

ثم انتقل إلى بياريتز خلال صيف 1921. ورقص مع جان بيرو المدعوة مونا بايفا، وهو أول تعاون له مع راقصة نجمة.

وفي أكتوبر لعب الراقصان في الأوبرا الكوميدية في “(…) باليه لجان هوري في “الغابة المقدسة” والتي أعدتها لويز ستيشيل المعينة مسؤولة عن الباليه “بخيالها الذي لا ينضب”. اعتمدت طريقة جديدة بالكورال والحكايات، صونيا (بافلوفا)، أدّتْ فقرتها كما لو كانت حورية البحر، صفق لها الجمهور طويلا، وكذلك جان برويكس، المدعوة مونا بايفا وغاستون جيرليس، الذين وظفا حديثا”.

[49]

في 1923، سمي غاستون راقصا أول في الأوبرا الكوميدية، حيث كان يلعب في عدة مشاهد. “فمن بين نجوم الاستعراض المقبل، “في كامل الجنون”، تمّت الإشارة إلى غاستون جيرليس راقص أول في الأوبرا الكوميدية، والذي أدى إبداعات جيدة أظهر خلالها، مرة أخرى، ميزاته في التوليف الكوريغرافي وتقنيته الواثقة والمحببة في قاعة نافار”.[50] “. كانتْ شريكته آنذاك ليديا جونسون [51] التي سيسمح الحظ لجرليس بالالتقاء بها في عدة أدوار . اهتم به النقاد جيدا ووصفوه بكونه راقصا “جذابا” وبأنه “واحد من أمهر راقصينا”… في غالبية المشاهد ظهر الراقص، غاستون جرليس، المعار من الأوبرا الكوميدية أظهر نفسه حقيقة من طبقة جد راقية”. وكُتب عنه كذلك بأنه “راقص جد معروف بالرقة والقوة والمرونة”.[52],[53] [54]

في 1924 قدم مع راقصة أخرى في مسرح السفراء عرضا بعنوان “يا للأناقة”. “غاستون جرليس هو الشريك المثالي للآنسة نابياركوفسكا، والتي تقاسم معها التشجيعات الحماسية للجمهور. مرن ومُتيقظ، عصبي وقوي وذو خلقة مثالية، غاستون جرليس يرقص بمهارة، بدقة وثقة لا مثيل لهما. كان تطوره متواصلا وسريعا، وهو ما أظهره مرة أخرى على خشبة السفراء.[55]

أتاح له النجاح فرصا جديدة. وهكذا انضم إلى الفرقة التي ستلعب الكوميديا الموسيقية الجديدة لساشا غيتري ورينالدو، “موزارت”، التي أخرجها مسرح إدوارد السابع يوم فاتح دجنبر 1925، إلى جانب ساشا غيتري نفسه وإيفون بيرانتون.[56]

ملصق [57]

دائما بنفس النشاط سيواصل غاستون جيرليس العروض مع شريكته الجديدة : ديان بيلي.

“لكن الراقصين غاستون جرليس وديان بيلي، لن ينضما أبدا لهذا البرنامج الجديد “الإمبراطورية” والذي يستحق التنويه، بالنظر لطريقة تقديمه وجماليته وأزيائه و”عُريه” (من السهل وضع اللباس على البقاء عاريا ) وعمله وأبحاثه الشخصية. بلا شك فالعديد من أدواره كراقص في عروض مسارح فولي بيرجير، والسفراء، ومايول، بعد بداياته المبهرة في الأوبرا الكوميدية، مكّنت غاستون جيرليس من إبراز قدرته الكوريغرافية، وإظهار لياقته، وإبراز عصبيته اللطيفة التي تُنشط أداءه”.[58]

ملصق ديان بيلي وغاستون جرليس[59]

على إثر نجاحاته المتعددة، سيحقق غاستون جرليس مسارا مهنيا على المستوى الدولي. بدأ بألمانيا “من ميونيخ – نعلم نجاحه الجيد الذي تحقق في عرض المسرح الألماني من طرف الثنائي الفرنسي الراقص غاستون جرليس وليزيا”، [60]“، ثم نجده في برلين وفي فرانكفورت. وفي 1929 كان في إسبانيا، وفي 1930 في لندن، وفي 1931 في الجزائر ثم في بيونس إيرس والأرجنتين.

“من بيونس إيرس – كل نخبة المجتمع الأرجنتيني وأعضاء الجالية الفرنسية حضروا للبدايات المثيرة للراقصين غاستون جرليس وليزيا بمناسبة إعادة افتتاح لا رمونونفيل. كان نجاح هذين الراقصين المشهورين كبيرا. [61]

بعد الرجوع إلى أوربا سنة 1932، كان في إسكاندنافيا، ثم في 1935 مرة أخرى في لندن، “من لندن –الراقصان الفرنسيان غاستون جرليس وليديا، اللذان قاما، وبنجاح باهر، بجولة في مسارح بارامونت، واتفقا على عقد هام يتعلق بعرض خاص بأستراليا، وسيغادران إليها يوم 27 من الشهر الجاري”.[62]

غاستون جرليس وليديا[63]

حينما يكون في فرنسا بين سفرين، يستمر في الرقص في مختلف العروض. هكذا في شتنبر 1936 “في تريانون مسرح المنوعات الذي يستعيد لنا في كل أسبوع نجما أو أكثر من نجومنا المفضّلين، أنجز غاستون جرليس وشريكته الرقيقة، بعد لندن والأمريكيتين، عودة ناجحة. فعرضهما تميّز بدقة الملاحظة التي نافست جرأة الأكروبات والمعرفة الكوريغرافية، وهو ما يفضله الإنجليز. ونحن كذلك”.[64]

دفعته شهرته أيضا لممارسة حياة اجتماعية : فقد شوهد في سياق الأيام الستة[65] ، يقدم المساعدة للحفل السنوي “الليلة الكبيرة للنجوم” مع فنانين آخرين من بينهم ميشيل سيمون، نظمته جريدة “هولاهي” لفائدة صندوق الإغاثة للجمعية العامة لطلبة باريس يوم الجمعة 18 ماي 1934، في صالونات مونسو[66] و خلال الصيف يقيم “عند نين صاحبة المطعم المعروفة في زنقة فكتور ماسي التي تسير فندقا بفال ديسكيير، غير بعيد عن تولون، قريبا من زبنائه الباريسيين”.[67] »

تظهر هذه الفقرات الأهمية التي يوليها المعلقون للشخص الذي وهب حياته كلها للرقص، والذي جاوزتْ سمعته الحدود.

وفي نونبر 1939، شارك في “مجموعة المجموعات”[68] مع ليديا، في آخر عرض بلغ إلى علمنا عن طريق الصحافة. فالحرب اندلعت ولم يعد هناك وقت الأفراح.

“حينما أرقص لا يمكنني أن أحكم، لا يمكنني أن أحقد، لا يمكنني أن أفترق عن الحياة. كل ما أستطيع أن أكون سعيدا وكاملا. لذلك أرقص”.[69]

في 1941 غاستون بالجزائر[70]

أسباب إقامته غير معروفة : هل للمشاركة في حفلات ؟ بدون شك. ويبقى السؤال المهم : لماذا لم يظل في الجزائر ؟ اليوم يظهر ذلك بديهيا لأننا نعرف بقية الحكاية. لكن حينما نكون مكانه يصبح ذلك معقدا. البقاء في الجزائر العاصمة؟ التخلي عمّا يشكلها ؟ الذين نحبهم، الذين أحبهم، أزقة باريس، الأصدقاء ؟ مجموعات العروض، المسارح، الحياة الجميلة بين عرضين، كل هذا العالم المحموم، مسرح المنوعات؟ التخلي عن كل شيء ؟ لا يقرر ما يفعل.

ورغم ذلك فهناك إمكانية الالتحاق بتونس، مسقط رأسه، ولكن لم تعد تربطه رابطة بالبد، فوالداه قطعا الجسور بعد وصولهما إلى فرنسا. والأكثر من ذلك أنه لا يمكنه ممارسة عمله، حقيقة وجوده. ذلك أن عالم الرقص قد تغيّر بتونس. حيث أصبحت الموضة للراقصات.

طبعا هناك القوانين التي صدرت بخصوص النظام الخاص باليهود، مما جعل من هؤلاء فئة منفصلة عن الساكنة. يحدد الفصل التاسع من قانون اليهود لشهر أكتوبر 1940، ثم الفصل 11 من تشريع 11 يونيو 1941 الخاص باليهود، بأن هذا التشريع يطبق على الجزائر والمستعمرات، والدول المحمية والأراضي تحت الوصاية“”. لكن غاستون لم ينشغل يوما بالسياسة ولم يحس بنفسه معنيا بها. قيل له بأن النظام في المنطقة الحرة يختلف حسب جنسية الأشخاص بين المنحدرين من الدول المعنية الملحقة بالرايخ، والأجانب العاديين والفرنسيين.

من الجزائر إذن ركب الباخرة إلى مارسيليا، ثم القطار إلى ليون. كانت المدينة في المنطقة الحرة وتضم طائفة يهودية مهمة، من بينها مزدادون بتونس. ومثلما هو الحال في عموم فرنسا، كانت الطائفة اليهودية تحس بنفسها مندمجة ولم تفكر في أنه ينبغي لها أن تغادر. وبدون شك فكّر غاستون بأنه سيكون هناك في مأمن كما سيجد المساعدة. لكن من سخرية الأقدار أنه من خلال ديانة لا يمارسها تمنّى لو ينجو بذاته.

من الضوء إلى الظل

في ليون، سكن بالرقم 10 زنقة دوبوا في الدائرة الثانية، بفندق بروطاني، في بناية قديمة [71]ومعروفة تقع في موقع جيد قرب المحطة وغير بعيد عن ساحة بلكور حيث تعيش العائلات اليهودية التونسية.[72]

اعتقل غاستون في ليون يوم 17 يوليوز 1944 لسبب “عرقي”. هل حدث ذلك في الشارع ؟ أم في الفندق والذي كان يحتفظ بسجلات المسافرين ؟ ثم نُقل إلى السجن بحصن مونتلوك. لم توضع له أية بطاقة، توجد فقط ملاحظة مسجلة في جزء من ورقة.[73].

بعد أيام من ذلك نُقل إلى درانسي التي وصلها يوم 24 يوليوز 1944 وسُجن تحت رقم 25.745 . وحسب كناش التفتيش رقم [74]157 كان يملك 1875 فرنكا. هذا الراقص الرقيق والحساس والذي عاش “حياة خصبة من الملذات”، واجه ظروفا كارثية : اختلاط، غياب النظافة، الجوع، العطش، ففي أي حالة نفسية كان غاستون ؟

في 31 يوليوز 1944، صعد إلى آخر قافلة حملت اليهود إلى درانسي بأوشفيتز. لأنه في فرنسا، كما في غيرها، كان استعمال القطارات ضروريا “من أجل تنفيذ الحل النهائي للمسألة اليهودية بأوربا”.[75]

خريطة شبكة السكة الحديدية في أوربا[76]

خلال أربع نهارات وثلاث ليال طويلة، سارت العربات المكدّسة بلا تهوية وبلا ضوء ولا أكل وقليل من الماء. ومع الحرارة الخانقة، تصبح الروائح كريهة. كيف حاول غاستون الهروب من هذا المناخ المختنق ؟ هل رأى حينها صور حياته تمر أمام عينيه ؟ هل سمع موسيقى الباليه والمجموعات الاستعراضية ؟ هل يعلم بأن والديه المسنين قد نجيا ؟ هل تصور بأن ألمانيا المتحضرة، ألمانيا الفلسفة والموسيقى، الموسيقى التي استقبلته وصفقت له كثيرا قد تعرضتْ “لقطيعة حضارية[77] “، قطعا لا

أخيرا في ثالث غشت 1944 توقف القطار في صوت حاد، ثم سُمع صرير الأبواب وصيحات الركاب وهم يخرجون من العربات. لقد وصل. وباعتباره شابا يتمتع بصحة جيدة، فقد وُضع في صف القادرين على الشغل. وتوا بدأت تتتابع الممارسات الإنسانية : حجز بعض الحاجيات الشخصية، التعرية، حلاقة الشعر، وشم الذراع الأيسر بالرقم ب3920، والملابس الكبيرة جدا أو الصغيرة جدا المأخوذة من الأموات. لم يبق شيء من “الحياة السابقة”، ثم وُجه نحو الكوخ حيث وجد ابني خاله : فكتور وجاك دريان.[78]

ومثل ابني خاله، تم إلحاقه بالكومندو بترسون كاناليزايشن ليحفر خنادق خارج المعسكر. ومثل الآخرين، عمل غاستون في ظروف جد صعبة، منذ طلوع النهار، بعد النداء الصباحي في الساحة. العمل مرهق والذين يتوقفون يتعرضون للضرب، وأحيانا حتى الموت. أما الفطور فيتكون من حساء.

وفي منتصف شتنبر، كان غاستون جد مريض. رغم “طابعه القوي والتطوعي” فإنه لم يتحمّل ظروف الحياة القاسية. ملأ قلبه الرعب وأحسّ بنفسه مكسرا بفعل هذه القساوة واللاإنسانية. كان مهزوما إزاء وضعية غير مفهومة وميؤوس منها، لم يعد قادرا على المقاومة.

“من الأبدية لم يعدْ لي انشغال،

هذا الشوق الإلهي، لم يعد لي أيضا،

و آلهات الفن تهْربن مني كالغريبات”.[79]

ذات مساء، تم اختياره، “فمساء يوم ثاني أكتوبر، سمع النداء، دون إخبار سابق. تمّت تعرية كل السجناء أمام ضابط، سجل أرقام أولئك الذين سيتعرضون للغاز، ومعهم غاستون.[80]

نداء (رول-كول 1941-1942) لوينسانتي غاورون[81]

تمت قيادة غاستون مع الآخرين الذين وقع عليهم “الاختيار” نحو بيركوناو . “يومان بعد ذلك، 800 يهودي رموا في المحرقة ومن بينهم غاستون”.

بعد الحرب، وبصفته “أحد قدماء الاعتقال” قدّم فكتور درياي شهادة في حق غاستون يقول فيها : “تمكّنت من معاينة جميع العلامات الخارجية التي كانت تصاحب تصفية المعتقلين مثل الدخان واللهيب الخارج من الأفران، رائحة اللحم المحترق التي كانت تنتشر على مسافة كبيرة، إرجاع ملابس السجناء إلى المعسكر”.[82]

الألم اللانهائي

على ما يبدو فوالدا غاستون وكذلك أخوه ألبير شرعوا في البحث عنه مبكرا. وفعلا فمنذ 12 أكتوبر 1944 تسلموا شهادة من مدير مصالح السجلات والإحصائيات بوزارة الأسرى والمرحّلين واللاجئين يؤكد فيها بأنه، حسب الأرشيفات، فقد قُبض على غاستون في ليون، وسّجن في معسكر درانسي من يوم 24 يوليوز 1944 إلى 31 يوليوز1944 تاريخ ترحيله.

بعد الحرب، قام فكتور وجاك درياي، اللذان نجيا، بإخبار عائلة غاستون بالذي حصل. فكيف نعبر عمّا يصعب وصفه ؟ ما هي الكلمات التي استعملاها ؟ ماذا قالا وماذا لم يقولا ؟ بكل شجاعة، قام جوزيف سكنازي بالإجراءات الضرورية للحصول على شهادة نموذج “م” رقم 18.083 والتي سُلمت له يوم 21 مارس 1946.

وتبعا لتصريح فكتور درياي : “بالنظر للوقائع المقدمة، يمكنني أن أشهد تحت أداء اليمين بأن ابن خالي المختفي إلى اليوم قد توفي في الظروف المعروضة”[83]“. شهادة وفاة غاستون مؤرخة في سابع يناير 1947، وسجلت يوم عاشر نونبر 1947 بسجلات الحالة المدنية في الدائرة العاشرة بباريس.

وبطلب من والده فإن صفة “متوفىّ من أجل فرنسا” قد قُيدت في وثيقة وفاته، بتاريخ 13 يناير 1948.

وفي أبريل 1951 تسلّمت العائلة شهادة “من أجل تطبيق الإعفاء من حق التنقيل بسبب الوفاة لصالح ورثة ضحايا الحرب طبقا للفصلين 10 و12 من قانون 31 دجنبر 1939” مع صيغة تُوضح سبب الوفاة وهي “التصفية في معسكر للترحيل”.

فيليسي لن تعيش نهاية هذا الملف. فقد حطمتها وفاة ابنها في ظروف لم تفهمها ولكننا نفهم جانبها الفظيع. عدم وجود قبر لا يمكنها من الترحم عليه، ولا أن تمارس الحداد شيئا فشيئا. توفيت في عاشر فبراير 1950.

جوزيف منهار، مكسور بالألم على إثر هذه الوفيات المتوالية. أما الإجراءات الإدارية التي باشرها لتسجيل ابنه في كناش الوفيات مع الصيغ الملائمة والاعتراف المناسب، فلن تُعوض غيابه، إذ ازداد الفراغ حوله أكثر فأكثر عمقا إلى أن توفي في سابع فبراير 1953.

هكذا تولى ألبير الملف. في نونبر 1953. قدّم طلبا لتخويل صفة “مرحّل سياسي” لأخيه غاستون والذي مُنحها في 19 دجنبر 1955، منهيا بذلك إحدى عشر سنة من المساطر الإدارية، وعندها لم تبق هناك سوى ذكرى أخ محبوب اختفى بشكل تراجيدي.

Français

Français Polski

Polski