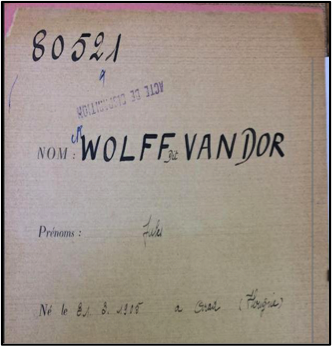

Gyula WOLFF-VANDOR

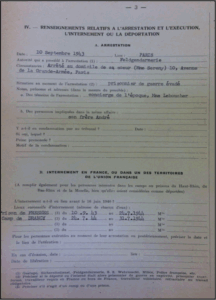

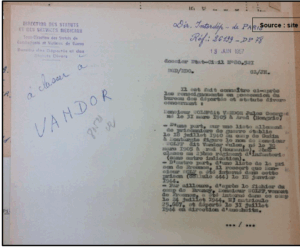

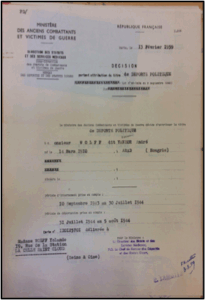

The record on the left, in the name of Jules Wolff-Vandor is from an application to have him recognized as a having been a political deportee. © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Normandy Dossier n°21-P-551-069

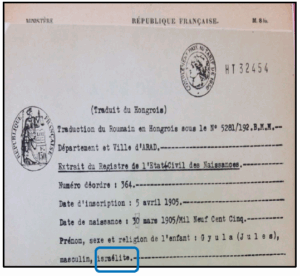

Gyula (also known as Jules, Georges and Jules-Georges) Wolff-Vandor was born on March 31, 1905 in Arad, in what was then Transylvania, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was Hungarian citizen.

His parents were Jenö (Eugène) Wolff, a wine merchant born on January 7, 1878 in Glogovăt, and Jolan (Yolande) Fleischer, born on October 13, 1882 in Arad. Jenö’s parents were Alexandru Wolff and Paulina Stein, while Jolan’s parents were Vilhelm Fleischer and de Pepi Doman. The family was Jewish.

Gyula was the eldest of three siblings. He had a brother, Andras (André) Wolff-Vandor born on March 14, 1910 in Arad, and a sister Elisabeth, born on April 4, 1908, also in Arad[1].

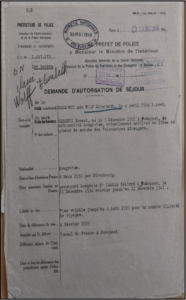

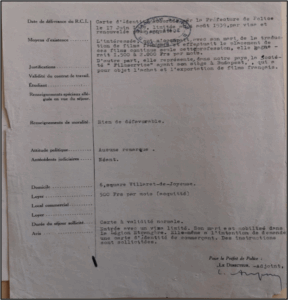

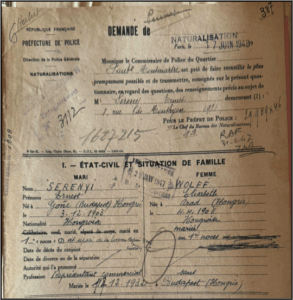

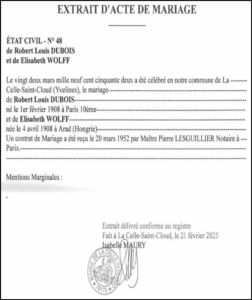

Elisabeth married for the first time in 1932. Her husband was Ernest Serenyi, who was born on December 3, 1903 in Budapest, Hungary. He joined the R.M.V.E. (Régiment de Marche des Volontaires Étrangers or Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers) in Paris at the start of the war. Twenty years later, she got married again, this time to Robert Louis Dubois, an electrical engineer who was born on February 1, 1907 in the 10th district of Paris, and died on December 3, 1960 in La Celle Saint-Cloud, in the Yvelines department of France.

Pages from Elisabeth Wolff’s residence permit application. © French National Archives, Moscow collection, Dossier n°19940485/6

A page from Elisabeth Wolff’s application to be naturalized as a French citizen, after the war, in 1946. © French National Archives, Moscow collection, Dossier n°19940485/6

Elisabeth Wolff and Robert Louis Dubois’ marriage certificate

© La Celle-Saint-Cloud municipal archives

The brothers’ arrival in France

Driven from their homeland as a result of the Nationalists’ anti-Semitic persecution, the Wolff brothers migrated to France. They arrived in Paris on or before July 1, 1939.

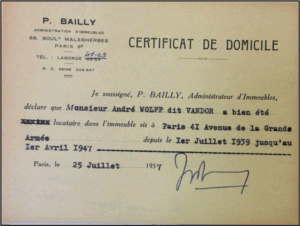

André Wolff-Vandor’s residency certificate, covering the period July 1, 1939 to April 1, 1947 © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

View of the Avenue de la Grande Armée from the Arc de Triomphe, Paris 1931,

© French National Library, Gallica

A page from a report by the Paris Police Headquarters on Gyula (now known as Jules) Wolff-Vandor’s civil status. It describes his religion as “Israelite”, i.e. “Jewish” © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-069

When they were arrested, the brothers were staying with their sister at 41, avenue de la Grande-Armée, in the 16th district of Paris. Elisabeth had arrived in France, via Strasbourg, on March 6, 1939, on a short-term visa that allowed her to work in the film industry for a company called Filmservice. She and her husband Ernest were to look for French films to export to Hungary, which they were to translate. The war soon put an end to their plans.

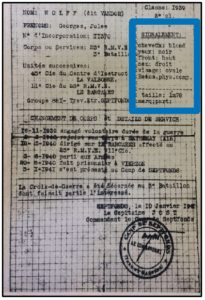

Jules-Georges left his former job as a draughtsman (a profession his brother also worked in), and joined the French Foreign Legion on November 16, 1939 at the Reuilly barracks in Paris. He signed up for the duration of the war. He completed his training in the infantry as a non-commissioned soldier (second class) with the 45th company at the training center in La Valbonne, in the Alpes-Maritimes department of France, with the regimental number 11370. On May 18, 1940, as soon as it was formed, he joined the 23rd R.M.V.E. (Régiment de Marche des Volontaires Étrangers or Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers) in Le Barcarès, in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France. He served in the 3rd battalion, and won the French War Cross.

Page from Gyula/Jules Wolff-Vandor’s military service record © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-069.

This service record retraces Jules’ military career, which began when he enlisted as a volunteer in November 1939. He was later awarded the French War Cross for his bravery in battle. It also provides us with some information about his physical appearance: he was 5’10” tall, had blond hair, black eyes, a high forehead, a straight nose and an oval face. He had no distinguishing marks. Since we have no photograph(s) of him, these are the only details we have about what he looked like.

Jules-Georges arrived on the front line on June 3, 1940 and fought with his unit against the German army [2]. He was taken prisoner of war 17 days later at Vierzon, in the Cher department of France, and then, after the Germans defeated France in June 1940, was interned in the nearby “Camp Sourioux”[3].

According to a list of prisoners of war drawn up by the Germans, he was interned on July 18, 1940 at the Gudin camp in Montargis, in the Loiret department of France, from which he escaped. In September 1957, when his sister sought information on her brother’s time in the army, with a view to claiming a pension, she was told that her request had been forwarded to the appropriate ministry.

On January 3, 1941, Jules-Georges “reported” to the Vichy government-run foreign workers’ camp at Septfonds, in the Tarn-et-Garonne department of France[4]. He was assigned to foreign workers’ group 881, and carried out forestry work in very harsh conditions. It appears that he escaped from the camp, but we were unable to find any details about this.

An escaped prisoner and Resistance member

After that, Jules-Georges returned to Paris. He and his brother André joined the Resistance, and went on to make use of their technical drawing skills. It appears to have been around this time that they began using the surname “Vandor” in addition to the name Wolff. In Hungarian, “Vándor” means “wanderer”, so perhaps they chose this name to reflect their Hungarian-Jewish roots.

The two brothers then begin forging identity papers for Resistance fighters.

It was for this reason, coupled with Jules-Georges’ status as an “escaped prisoner of war”, that on September 10, 1943, the Feldgendarmerie (German military police) arrested the brothers at their sister’s apartment at 41 avenue de la Grande-Armée, in the 16th district of Paris. A record held by the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War states that the concierge, a Mrs. Leboucher, witnessed the arrest.

Another record, containing information provided by the family, says “Arrested at his sister, Mrs. Sereny‘s home [by the Feldgendarmerie], at ’10’, avenue de la Grande-Armée, Paris” [with] his brother André“; “Accused of having made up false papers (as draftsmen) for Resistance members; [they] then apparently discovered his Jewish origins.”

This proves that the Wolff-Vandor brothers were involved in the Resistance[6].

These records give the reasons for which the Wolff-Vandor brothers were arrested on September 10, 1943. André Wolff-Vandor, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024, Jules Wolff-Vandor, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-069

Deported and murdered because he was Jewish

Jules-Georges and his brother André were imprisoned in Fresnes, in the Val-de-Marne department of France, on the day that they were arrested.

During the Occupation, “Fresnes prison was the largest repression center for Resistance fighters”[7]. During their time there, Gyula and André, along with many other Resistance fighters, were forced to live in inhumane conditions: the place was overcrowded, tortured was commonplace, and so on.

Jules-Georges was held in cell number 542[8] and/or 444; on January 18, 1944, he was moved from one cell to another. The two brothers remained in Fresnes until July 24, 1944. Listed as Jewish prisoners (rather than Resistance members), they were sent to Drancy internment camp, north of Paris, where the Germans were planning to send one last transport to Auschwitz[9].

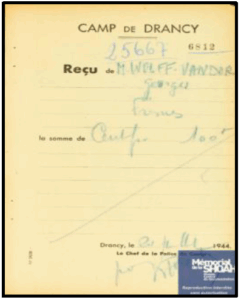

In July 1944, SS Officer Hauptsturmführer Aloïs Brunner was in charge of Drancy camp. Following the Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, Brunner set about deporting as many Jews as possible before time ran out[10]. When Jules-Georges arrived in Drancy on July 24, he was searched and had 100 francs confiscated from him. He was then assigned the registration number 25,667 and sent to a 5th floor room on staircase 18.

Jules-Georges (now listed as Georges) Wolff-Vandor’s search receipt from Drancy camp

© Shoah Memorial, Paris

Living conditions in the camp were truly appalling: filthy conditions, hunger, severe overcrowding, disease, deprivation etc.

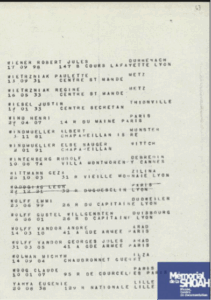

On the morning of July 31, 1944, Jules-Georges, André and all the Drancy internees who were listed for deportation were loaded onto buses run by the Paris public transport company, and taken to the nearby Bobigny station, where a train was waiting for them.

The train, which belonged to the French National Railway Company, the S.N.C.F. was made up of 30 cattle cars. 1306 people, including 324 children were forcibly loaded onto the train. It set off around midday, passed through the French cities of Châlons-Sur-Marne and Metz, and by the morning of August 1, it had reached Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany.

The traveling conditions on the train were absolutely appalling[11]: the stifling heat of summer 1944 , 60 or more people crammed into each car, straw on the floor, one bucket for their needs, hardly any drinking water, just a little bread to eat. When the train stopped, one person was allowed out to fetch a bucket of water.

The train arrived in Poland after passing through Görlitz, in Germany during the night of August 2, and finally reached Auschwitz II-Birkenau in Poland in the early hours of Thursday, August 3, 1944[12].

The original Convoy 77 deportation list, dated July 31, 1944 including the names of the two Wolff-Vandor brothers. © Shoah Memorial, Paris

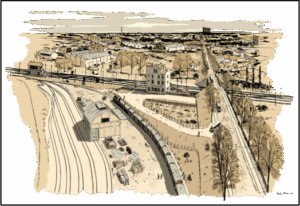

Image 1: Sketch of Bobigny station, as it was in 1943,

© Etienne Martin, LM Communiquer

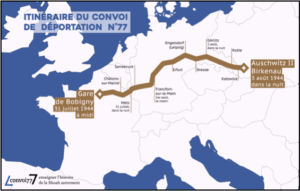

Image 2: The route taken by Convoy 77 Source: Convoy 77 nonprofit association

As soon as the train arrived at the camp, Georges-Jules was most likely sent to the gas chambers and murdered immediately. Although his death certificate officially states that he died on Saturday August 5, 1944, he was almost certainly murdered on August 3, on the same night as his brother André. However, given his age, it’s not inconceivable that he was selected to go into the camp to carry out forced labor.

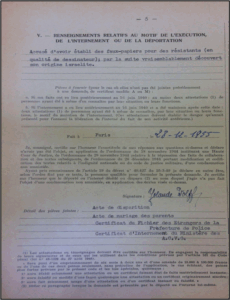

This summary from the “Department of Status and Medical Services for deportees” outlines the main ways in which Jules Wolff-Vandor was persecuted. © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-069

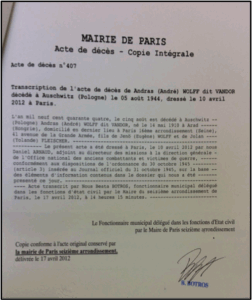

Andras (André) Wolff-Vandor’s death certificate, issued by Paris City Hall. © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-024

We have been unable to gather any further information about the brothers’ deportation[13].

After the war, their sister, Elisabeth, and their mother, Jolan/Yolande, filled in various forms and took all the necessary steps to have André et Jules-Georges officially recognized as “political deportees”. In France, this means that they were deported on political grounds, because they were Jewish, and must not be confused with the status of “deported Resistance fighter”. Their mother and sister did not apply to have them recognized as having worked for the Resistance movement. In addition, as far as we are aware, none of the Resistance networks listed the Wolff-Vandor brothers as members and no Resistance survivors ever made themselves known their family.

A page from Mrs. Yolande Wolff’s application to the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War to have her son, Mr. Gyula Wolff-Vandor, officially recognized as a political deportee. File on Jules Wolff-Vandor, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21-P-551-069

Elisabeth and Yolande’s fight for recognition of the brothers’ status as political deportees only finally came to an end in 1959. On February 13 of that year, Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War granted Gyula the status of “political deportee”, based on the period during which he was interned, September 10, 1943 to July 30, 1944, and subsequently deported, from July 31 to August 5, 1944 (not the actual but the official date of death, which was convenient for administrative purposes).

The time he spent in the camps in Vierzon, Gudin and Septfonds were not taken into account.

In March 2012, the French National Office for Veterans and War Victimes sought to have the words « Died during deportation » added to the brothers’ death certificates, although we were unable to find this in the records for the 16th district of Paris. It was finally done, however, on April 10, 2012.

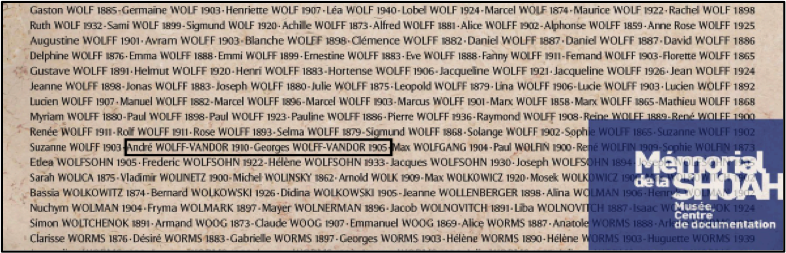

Lastly, Gyula, under the French version of his name, “Georges”, is listed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

The names of Georges Wolff-Vandor and his brother André are inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

© Shoah Memorial, Paris

We, Johann Culy-Quéré, Malo Le Cleach, Yannis Kpossa Mamadou, Antoine Cahu and Titouan Petit-Le Goff, 12th grade students at the Jacques Cartier high school in Saint-Malo, in the Ille-et-Vilaine department of France, wrote this biography of Gyula (Jules-Georges) Wolff-Vandor during the month of April, 2025, at the suggestion of our History and Geography teacher, Mr. Stéphane Autret.

In November 2024, during our research for the project, we also recorded a short podcast that tells part of his story, closely linked to that of Convoy 77.

We would like to thank Ms. Claire Podetti, the Convoy 77 project coordinator and Mr. Serge Klarsfeld, the president and founder of the nonprofit organization Fils et Filles de Déportés Juifs de France (Sons and daughters of Jewish deportees from France), as well as Mr. Nicolas Coiffait, a genealogist, for their invaluable help with our research.

Notes & references

[1] Unfortunately, our search for any possible descendants and our request to consult the archives in Arad were unsuccessful, so we were unable to find more details about the brothers’ genealogy, nor could we find a photograph of them.

[2] This is based on information from Mr. Tibor Szecsko, who wrote some books about the French Foreign Legion, that we found on the website dlezin.free.fr/Historiques_regimentaires/le_3-23e_RMVE.htm. On the advice of Mr. Serge Klarsfeld, we also tried to find out more from the Foreign Legion in Aubagne, in the Bouches-de-Rhone department of France, but to no avail.

[3] “Vierzon: le camp Sourioux, une page méconnue de l’histoire de la ville durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale”, (“Vierzon: Camp Sourioux, a little-known page in the town’s history during the Second World War”) © France Bleu website.

[4] Information obtained from the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service by Ms. Claire Stanislawski Birencwajg, who works at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

[5] Files on Jules Wolff-Vandor and André Wolff-Vandor, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier Nos. 21-P-551-069 and n°21-P-551-070, which states the reasons for the brothers’ arrest on September 10, 1943.

[6] Although we asked the Memorial in Caen, the Paris Archives service and the Paris Police Headquarters for more information, we were unable to find any further evidence of the brothers’ involvement in the Resistance.

[7] This is based on information from Mr. Loïc Diamani – a historian at the French National Resistance Museum in Champigny-Sur-Marne – gathered by the journalist Kanumera Creiche for an article in the French newspaper Le Monde, entitled “Le “couloir de la mort“ de la prison de Fresnes fait des histoires” (Fresnes prison’s “death row” is a hot topic”).

[8] Robert Dubois (who later married Elisabeth Wolff), who was then living at 4 square Raynouart, in the 16th district of Paris, searched for and found the cell number 542, which leads us to believe that the bothers were in touch with their sister during their time in Fresnes Prison. There is also evidence of Jules being in cell 444 in Fresnes on January 18, 1944 (record ref. LA 8426).

[9] We have no further information about their time in Fresnes, despite having asked the Val-de-Marne departmental archives service, as well as checking the registers 2742W 1, 2742W 101, 2742W 109, 2742W 43 and 2Y5 433.

[10] Convoy 77 website, page on the history and the make-up of the convoy, and Wikipedia, ”Convoi n°77 du 31 juillet 1944”.

[11] Based on information given by Ginette Kolinka – a Holocaust survivor who was deported on Convoy n°71; to Moussa Diop for the article “Ginette Kolinka : contre l’oubli”, © Mairie de Cenon.

[12] Convoy 77 website, page on the history and the make-up of the convoy, and Wikipedia, ”Convoi n°77 du 31 juillet 1944”.

[13] We were short of time, and in the end, we were unable to examine the Auschwitz archives for ourselves as we had originally intended.

Français

Français Polski

Polski