Josef LAUER

⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀

The Romanian years

The Lauer family originally came from the Bukovina region of Romania. For centuries, this multi-ethnic region was the historic heart of the Țara de Sus, the “High Country” of the Principality of Moldavia, which borders the north-eastern Carpathians. The northern half of the region has been part of Ukraine since 1991, but the southern half is still in Romania.

Josef was born in Suceava, which is now a large town with more than 90,000 inhabitants. It is a popular tourist destination due to its proximity to the UNESCO-listed Painted Monasteries of Bukovina. In 1901, there were 6,787 Jews living in Suceava, but only 900 of them were contributing members of the Jewish community¹.

The Beit Kadishi (house of farewells) in the Jewish cemetery in Chernivtsi

This photo by Julian Nyča is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Josef Lauer was born on August 28, 1900 in Suceava. He was the son of Moses Lauer and Sarah Weismann². His father was a dairyman and died before 1925.

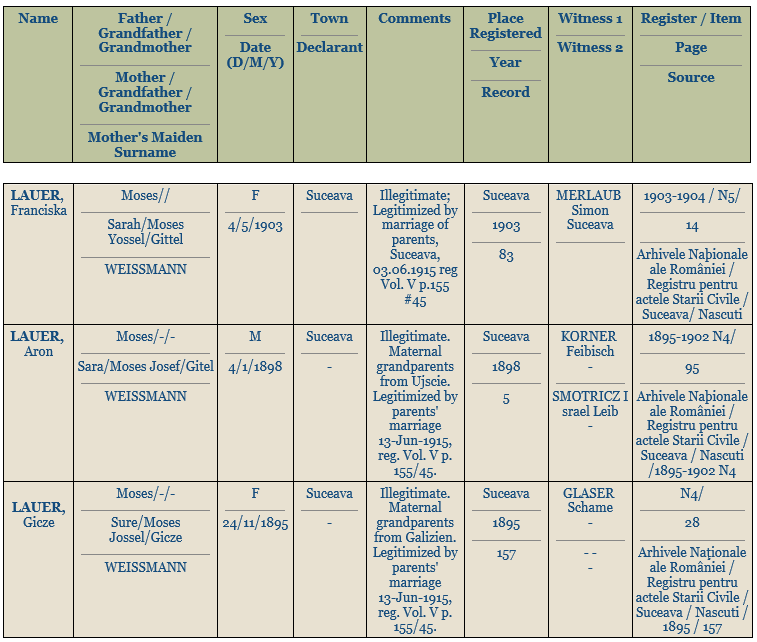

Although consulting Romanian civil status records is difficult, some information can be found in online genealogical databases.

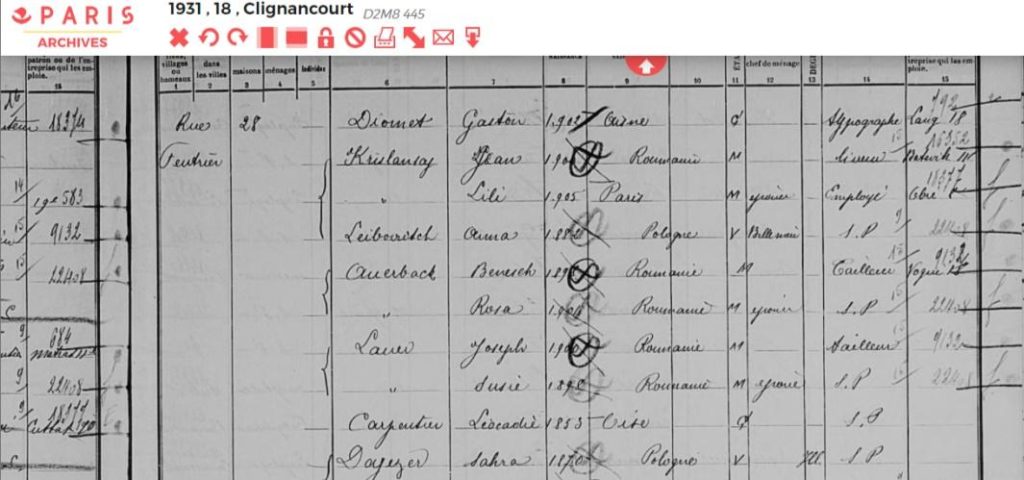

In a register of births in Bukovina published by JEWISHGEN³, one can find not only Josef but also his brother, Aron, born on January 4, 1898, and two sisters, Gicze, born on November 24, 1895, and Franciska, born on May 4, 1903. They were all born in Suceava.

All the children were considered to be “legitimized” when their parents got married on June 3 (or 13, since there was a typo), 1915, in Suceava. In fact, it was probably not a question of the births having taken place out of wedlock, but rather because there had never been a civil marriage until then, just a religious ceremony.

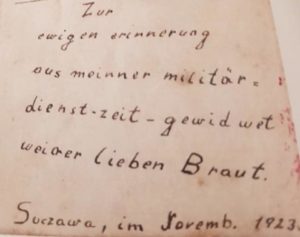

In November 1923, Josef began his military service, as evidenced by the photograph of him in uniform and the covering note in German addressed to I. LAUER⁴, 12 V.M. Komp. 4 M, SUCEAVA.

On January 21, 1925, Josef married Suzanne Fliegler, in the “Architectural Artisans Hall” in Cernauti⁵, which was also in Bukovina. Before their wedding, they both lived on the same street in Cernauti. He lived at 19, General Averescu street, while she lived at 11a⁶.

Cernauti and Suceava are only about 55 miles apart. In 1930, Czernowitz (its German name, now Chernivtsi in Ukrainian) was the capital of Bukovina and had a population of 200,000, half of which was Jewish.

Suzanne Fliegler was born on December 27, 1898 in Cernauti. Her father, Elias, was a carpenter and still living at when she got married. Her mother, Perl, was born Weissmann (as was Josef’s mother; perhaps the bride and groom were cousins?).

In Bukovina, the first anti-Semitic demonstrations appear to have begun in 1926, with the murder of a Jewish student, and to have intensified in 1930. Perhaps this was the reason that Joseph and his wife left, along with the global economic crisis.

The first few years in France

Joseph apparently arrived in France on December 1, 1929, while Suzanne may have arrived a year later⁷. He held a foreigner’s identity card No. 31 CP 11223, which was valid until October 23, 1943.

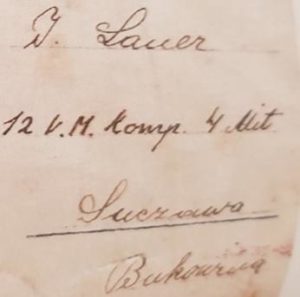

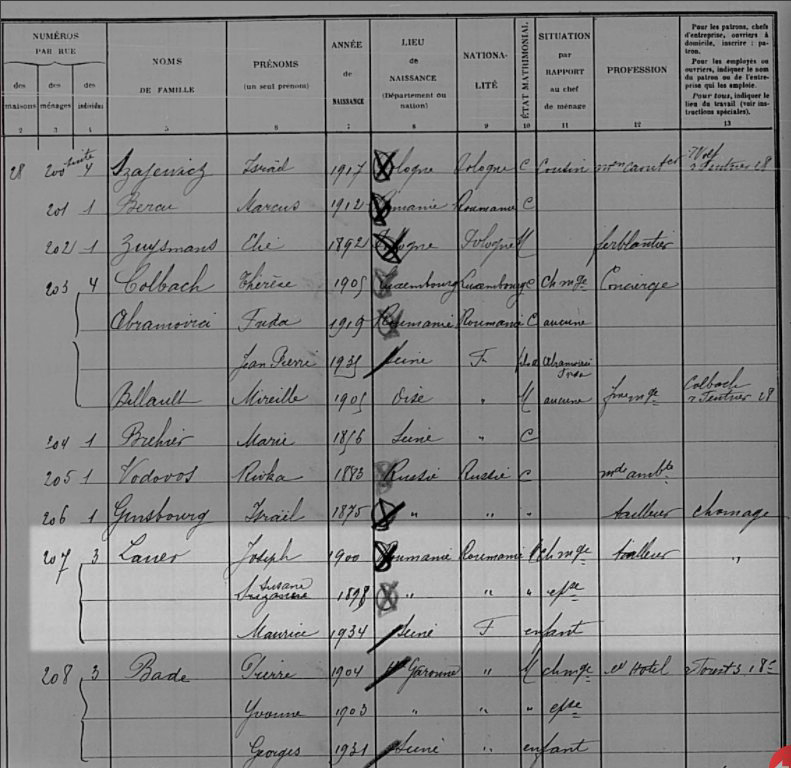

The 1931 census shows them living at 28 rue Feutrier, in the 18th district of Paris. This same record shows that Suzanne’s sister, Rosa, and her husband, Benesch Auerbach⁸, were living at the same address⁹.

The building today

1931 census

The Lauers were still living on rue Feutrier in 1936, with their first son, Maurice, as listed in the census¹⁰. This address was also recorded on their second child’s birth certificate, in 1937.

1936 census

Maurice and Elie were born on April 11, 1934 and May 16, 1937¹¹ respectively, both at the Lariboisière Hospital¹²

In passing, what follows is an amusing description of the problems in the neighborhood around the hospital before the war. It gives an idea of the local life and the noises that Suzanne might have encountered at the time.

The problems facing Paris-Lariboisière¹³

In the 1930s, the Barbès neighborhood was already quite turbulent and we realize today that Lariboisière’s woes are nothing new. Even back then, people complained about the noise and congestion.

The traders’ vehicles (many of them horse-drawn) and the fruit and vegetable merchants’ handcarts cluttered the roadway, obstructing the flow of the hospital cars and even preventing the (numerous) funeral processions from leaving. The vendors themselves did not make it easy for the patients to get to the door of the maternity department. As for the city police, who were frequently called out by the manager of the hospital, even they had great difficulty in restoring any semblance of order in the midst of such anarchy.

Not only that, but every year a fair was held on this boulevard, which was very popular in the neighborhood. Late into the night, there were entertainers shouting, jugglers canvassing passers-by, carousels clattering and barrel organs blaring out music.

To try to ensure that the sleep of new mothers whose windows overlooked the stalls was not disturbed, the only recourse was to call the Police Chief, who dispatched the city constables.

The pre-war period

Little is known about the period between 1938 and 1942, apart from the fact that the family moved into 42, rue de Clignancourt in the 18th district of Paris¹⁴. Their apartment was on staircase B, 2nd floor, the door on the right.

At that time, Joseph was working at home. The workshop where he had his cutting table was in one of the rooms of the apartment, and he marketed his goods directly to the major fashion houses.

Henri was born on November 24, 1939 in the 10th district of Paris¹⁵, followed by Paulette, on January 29, 1942, at the Bretonneau Hospital¹⁶.

The children attended the school on rue de Clignancourt, which was not entirely risk-free.

At the time, Elie had long curly hair. To hide him from the Germans, he was even disguised as a girl and sent to the girls’ school. The headmistress was complicit in this and issued a school certificate. Elie did not like this at all and asked his cousin Annette to cut his hair close to his ears, which caused uproar in the family.

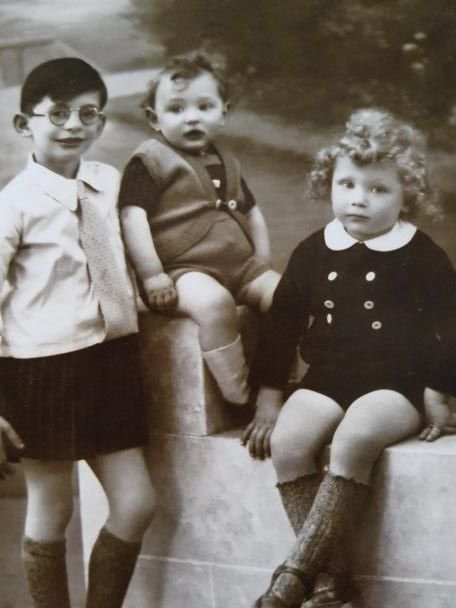

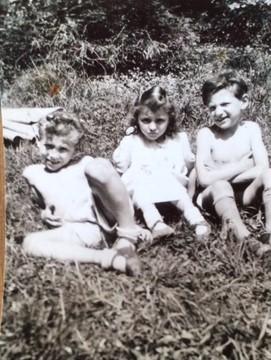

Maurice, Henri and Elie, around 1940

Hidden children, 1942-1944

Due to the round-ups of foreign Jews on July 16 and 17, 1942, including the Vel d’Hiv round-up, Paris was no longer safe.

The Lauer family was evicted from 42, rue de Clignancourt and their belongings were thrown out onto the street. They first sought refuge with some friends, on rue Feutrier.

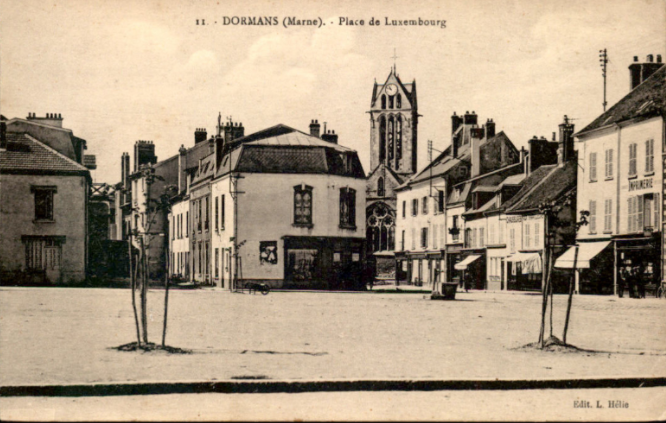

It became essential to hide the children. The 3 boys were evacuated from Paris and hidden first with the owner of a grocery store on place du Luxembourg, in Dormans, a small town on the banks of the Marne.

The Place du Luxembourg in Dormans

Elie remembers that the sugar was kept in his room and apple crates were stored under his bed.

He was not a timid boy, so he was given the task of taking the bowl to the dogs, who ate the same soup as the family. Because it was so good, he sometimes stole some of it on the way, and everyone wondered why the dog was losing weight.

Next, the three of them, along with their cousins Charles and Annette Auerbach¹⁷, were sent to Cuissai, near Alençon in the Orne department of France, where they stayed on a farm with a Madame Chouippe¹⁸.

Cuissai, in the Orne department, around the 1920s

The children went to the local school and were in a class for three grades. In the morning, they went to school (after a little nudge, because it was a mile and a half walk!).

They also went to church, because it was in their interest to know the Catholic prayers by heart!

From June 4 to August 12, 1944, during bombing raids, the children hid in the cowsheds, which were spared by the Allies, and slept with the cows. Elie remembers that on August 12, the Germans hurriedly evacuated the village, without even taking their belongings with them, and that the Americans arrived and handed out chewing gum and chocolate to the children. The same evening, they liberated the town of Alençon.

Elie has no recollection of being truly afraid and was completely unaware of the reasons why they had to live that way, or be separated from their parents.

On the other hand, he has a feeling (although he is not sure if it is a genuine recollection or if he imagined it) that their father visited them in Cussai and that they all ate eggs together. He now thinks that this is more like a dream. However, from 1942 to June 1944, Josef was still free, so may well have gone to see his children.

Then again, perhaps it was the lack of contact with the adults in their families that saved all these children who, unlike so many others, managed to slip through the net.

As for the parents, they were evicted from their apartment on rue de Clignancourt, either by the French police or the Militia, and all their belongings were dumped on the sidewalk. They initially took refuge with friends on rue Feutrier, then in a maid’s room on the seventh floor of 29, rue Meslay, in the 3rd district of Paris.

There was no elevator in the building and Suzanne, who has a serious heart condition, struggled to get up and down the seven flights of stairs.

The family survived thanks to the janitor, a Madame Long¹⁹, who risked her life to take food up to them.

It was probably around this time that Josef, who could no longer work at home because his business would have been Aryanized, was hired by a workshop off the Champs-Élysées in central Paris.

29 rue Meslay today

Arrest and deportation

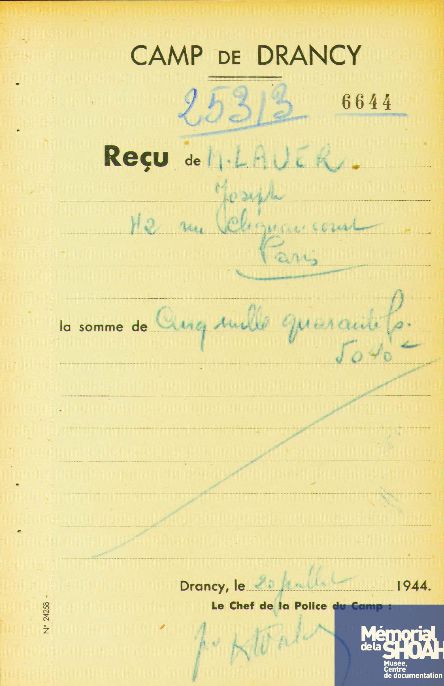

On July 19, 1944, at 11 a.m., Joseph was arrested by the French Police²⁰, at his workplace at 38, rue du Colisée, in the presence of his employer, Mr. Austen. He was sent to Drancy camp where the 5040 French francs (equivalent to around $950 nowadays) he had on him were confiscated²¹.

He only stayed in Drancy for about a week, after which he was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77²². The commander of Drancy camp, the SS officer Alois Brunner²³, who was close to Adolf Eichmann, was one of the most zealous perpetrators of the Final Solution. He was responsible for more than 1/3 of the deportations of Jews from France, including a large number of children.

Convoy n° 77 left Drancy camp on July 31, 1944: 1,309 people were deported, including 324 children and infants, all crammed into cattle cars. It arrived at Auschwitz during the night of August 3 and the “selection” took place immediately.

DRANCY search log

According to the work of German historian Volker Mall and survivors’ accounts, the chronology of events was as follows:

- July 31, 1944: 1,309 women, men and children departed from Drancy.

- August 3 ,1944: They arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, in Poland.

– 847 people were sent straight to the gas chambers.

– selected for work: 291 men (registration numbers B-3673 through B-3963) and 183 women (registration numbers A-16652 through A-16834).

- October 26, 1944: at least 75 men were transferred to the Stutthof concentration camp (registration numbers B-3675 through B-3955).

- October 28, 1944: they arrived at Stutthof, in Poland²⁴.

The Stutthof camp was near the former Free City of Danzig, in a marshy area on the coast of the Baltic Sea.

Joseph was thus admitted to the Auschwitz camp on the night of August 3. According to his registration number B 3836, he should have been part of the contingent sent to KL Stutthoff on October 26, 1944. This is also what is noted on his registration sheet. However, he never arrived..

Did he die during the 3 months he spent in Auschwitz? Or during the transfer to the Stutthoff? Since the Germans destroyed most of their records, the truth will never be revealed.

Convoy 77 was the last of the large deportation convoys to leave France. The Russian army liberated the Auschwitz camp on January 27, 1945.

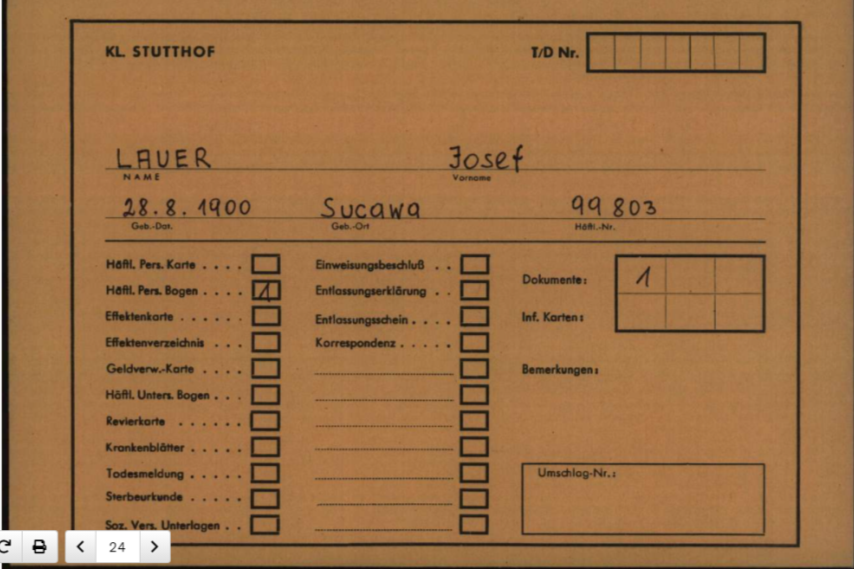

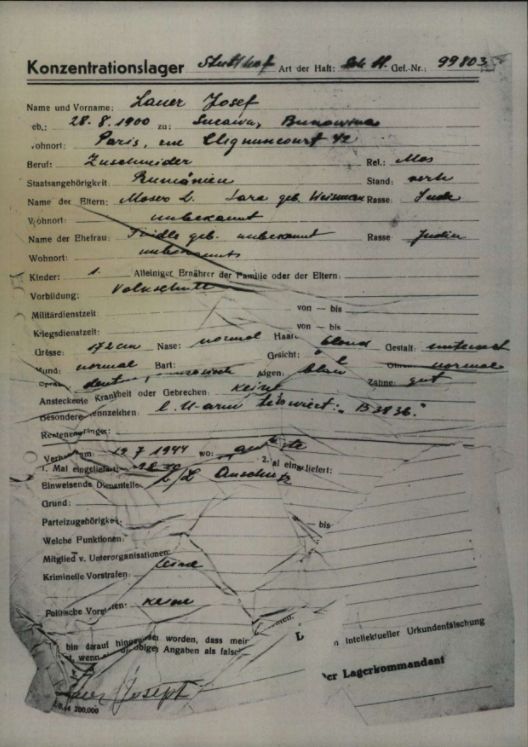

Information sheet drawn up at the Stutthof concentration camp ²⁵

Transcription and (approximate) translation of the information sheet

Concentration camp: STUTTHOF Detention category: ??? Prisoner number: 99,803

Surname and first name: LAUER Josef

Born on: 28/8/1900 at: SUCAWA, BUKOVINA

Address: Paris, 42 rue Clignancourt

Profession: Tailor and cutter Religion: Mosaic

Nationality: Romanian Marital status: married

Parents’ names: Moses L. and Sara WEISSMANN Race: Jewish

Address: unknown

Spouse’s surname: FIEDLE, née unknown Race: Jewish

Address: unknown

Children: / Sole guardian of the family or parents:

Level of education: Compulsory education

Military service:

Time spent in war service:

Height: 5’8” Nose: normal Hair: blonde

Mouth: normal Beard: Face: normal or oval?

Languages spoken: German,

… Eyes: blue Teeth: good

Infectious diseases or disabilities: no

Distinctive features: …. B3836 (= tattooed registration number)

Date …: 12/7/1944 Place: ???

1st time imprisoned: 2nd time imprisoned:

Internment bureau: KL Auschwitz

Several fields not filled in

Criminal record: no

Political report: no

Something along the lines of “certified sincere and true.”!

Signed on: 8/2/1944

Joseph LAUER

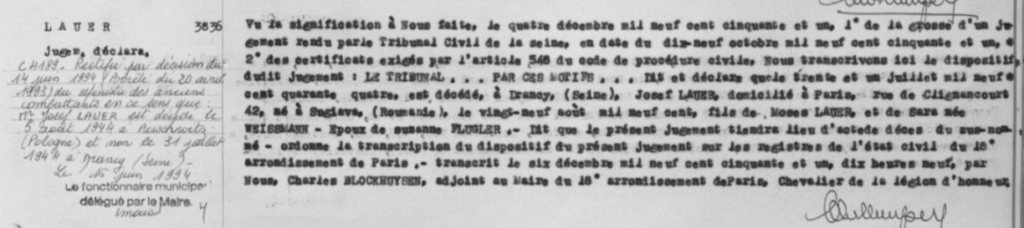

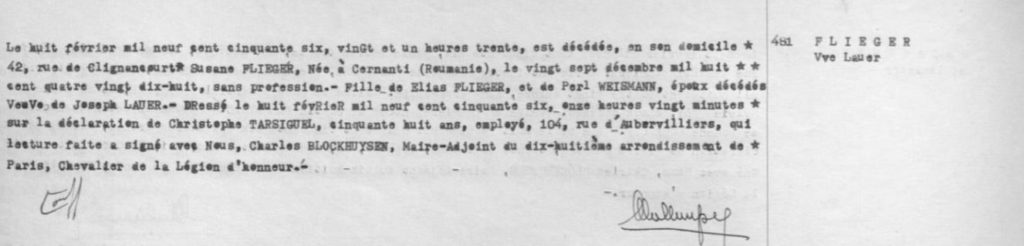

In the civil register, the deportees were initially declared to have died on the date on which they left Drancy. The registers were then amended in 1994, but the date of death recorded, August 5, 1944, was still a notional date that was used for all deportees who were not sent to into the concentration camp to work.

Archives of the 18th district of Paris, death certificate n°3836, view 15/31

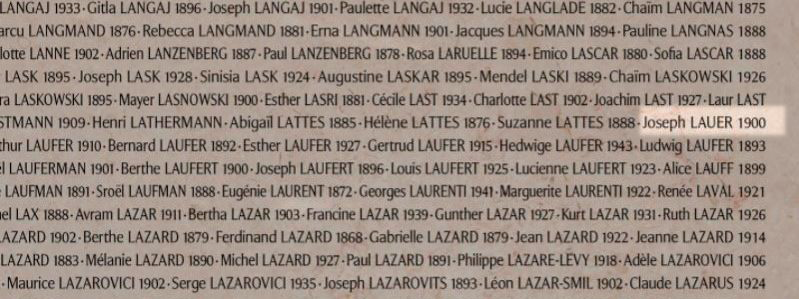

The Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, slab 23, column 8, row 2

After the war

At the time of the Liberation, Suzanne was living alone. She had serious heart problems, lived in a single room and had very little money. She was therefore unable to take care of four young children. Maurice was 11 years old, Elie was 8, Henri was 5 and Paulette was 3.

Elie, Paulette and Henri in about 1946

The boys were then moved out of Cuissai and placed in the care of the OSE, Organisation de Secours aux Enfants (Children’s Aid Organization).

This Jewish organization, founded in 1912, took in and hid many Jewish children during the war. It continued its mission after the Liberation, taking in children who had survived the camps, mostly orphans, but a high percentage of children remained in the homes although their father (for 27%) or their mother (for 12%) were still alive. The OSE ensured that the children had access to general education and some vocational training. For financial reasons, the children were encouraged to leave the homes when they turned eighteen.

The cost of keeping the children was minimal: in 1947, the OSE charged parents an average of 6,000 French francs per month²⁶. That was still too much for Suzanne, however. Fortunately, a rich cousin from Venezuela²⁷ sent her envelopes full of banknotes that were used to pay for their room and board.

From 1944 to 1946, the Lauer boys went to the following four centers:

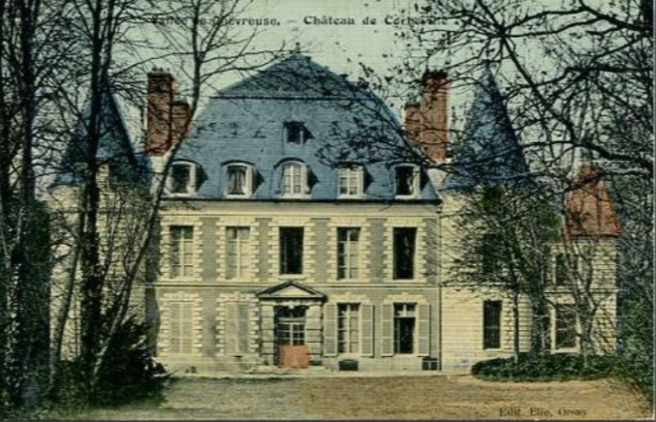

- The Château de Corbeville²⁸, a castle near Orsay, to the south west of Paris: Elie remembers a cave where the children gathered to play, and also the dormitory with a lot of beds in rows and the curtains separating the supervisor’s bed. After the more family-like atmosphere at the farm, Elie remembers crying and being very afraid of being separated from his brother.

Le château de Corbeville

- They were then transferred to the Château de Vaucelles, in Taverny, north of Paris. This was a religious center where they had to learn Hebrew and Judaism, which was not entirely to Elie’s liking²⁹. Nevertheless, as he was a strong boy, he had the great honor of carrying the Torah.

On Friday nights, he remembers helping the Polish cook to roll the dumplings.

They attended general education classes at the local school where there were sometimes pitched battles with the “others”. Elie soon learned how to defend himself after being subjected to some anti-Semitic comments by his classmates and became quite the brawler.

Le château de Vaucelles

Through the Marshall Plan, the OSE children were the first children in France to have jeans and Coca-Cola!

They were also sponsored by American families. Elie’s “sponsor”, Dr. Jacob Verne, once took him and a supervisor to the Grand Hotel restaurant when he was in Paris. Elie remembers eating chicken and French fries. When he asked what he would like as a gift, Elie asked for a fine bicycle, which shocked his supervisor. A few days later, however, Elie received his new bike.

- The Glycines Center, at Dravail, in the Essonne department. Glycine is French for wisteria. This time, the children were housed in small groups, and their relationships were generally very good, except for a few fights over girls, as the center was co-educational.

Once again, they had to walk a couple of miles to school in the morning. Fortunately, a charming woman from Draveil, Mrs. Gozzi, used to drive her 4CV on the return trip from the OSE and she used to give some of them a ride.

The Glycines Center

Some children received food parcels that they shared with their friends. Elie remembers a young boy who had just come back from a concentration camp. Many children were orphaned and adopted by Israeli, American or Australian families.

One day, Elie and a friend went to steal apples from the house next door. However, some of the stones in the wall came loose and fell on a cow that was grazing beside it. The cow didn’t give any milk for a week and the two boys were punished.

Some weekends, Elie would ride his bike to his mother’s house on Meslay Street and occasionally stayed the night with her in the tiny maid’s room.

- The last OSE center they stayed in was the Pauline-Godefroy home in Le Vesinet. This was a very lively place that had only opened in 1946. It was for boys only, about twenty of them between the ages of 17 and 22, while the girls were all placed together in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

The Pauline-Godefroy home

While he was there, Elie began studying electrical engineering.

Elie and Henri have very fond memories of the OSA homes where they had enough to eat, were well taken care of in a secure environment with an almost family-like atmosphere, and were surrounded by friends their own age, all of whom were in much the same situation. At least they still had their mother, and they still wished that their father would come back.

As for Paulette, who suffered from rickets due to dietary deficiencies, she was sent to the Hendaye Sanatorium in 1947. This institution, which was dependent on public funding, took in children from Paris who needed to nursed back to health³⁰. It was located more than 500 miles from Paris, which entailed what seemed like an endless journey for young children, not to mention the fact that they were separated from their families.

The Hendaye Sanitorium

While she was there, she was diagnosed with a hip deformity and had to have surgery in order to walk normally. She had two operations at the Hospital for Sick Children and was then sent, with her entire body in plaster, to the Maritime Hospital in Berck³¹, where she had a third operation, which finally proved successful.

The Calot hospital at Berck-Plage (Berck beach)

Her convalescence and physiotherapy meant that Paulette had to spend three interminable years in Berck, including two years when she was completely immobilized.

The patients lay on flat gurneys [with large wheels], called “gouttières“, which enabled them to remain lying down all the time, while still being able to be moved around.

Her family occasionally took a trip to visit her and take her for a ride on the beach on her special gurney.

She did not really become part of her family again until she was ten years old.

This inevitably had a negative impact on her education, although her curiosity and vivacity helped to make up for it.

Sick children in Berck

According to the census, at the beginning of 1946, Suzanne, who had an identity card³², was still living on rue Meslay with her 4 children. It was only in 1947, after many grueling formalities, that she finally managed to get back their apartment at 48, rue de Clignancourt.

48 rue de Clignancourt today

The children returned home one after the other, Maurice first, and Elie when he turned 18.

In 1950, Suzanne submitted a huge file in order to have Josef recognized as having been deported. This status was finally granted to him on December 1, 1955 (card no. 1101.18420).

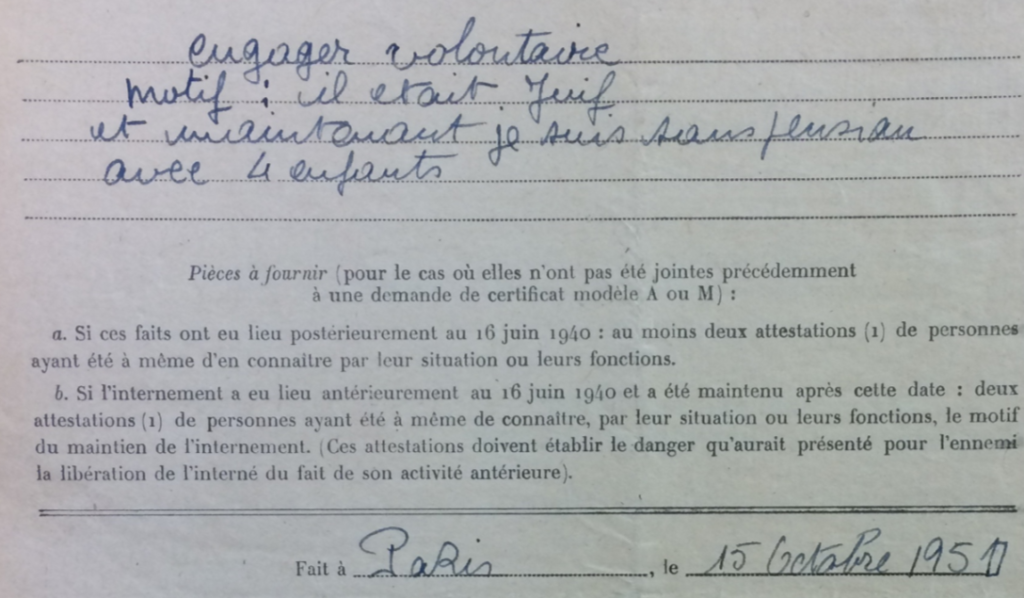

She had stated that he had been a volunteer in the French army³³ although his name is not on the list on the “Mémoire des hommes” (in Memory of the men) website.

The children were declared wards of the Nation in 1952: their birth certificates bear the inscription “adopted by the Nation, by virtue of a judgment passed on May 30, 1952 by the Civil Court of the Seine”.

Sick and exhausted, Suzanne was hospitalized several times.

One autumn evening in 1955³⁴, Paulette came home from school, and rang the doorbell as usual. Through the door, she heard her mother say weakly: “I can’t walk”. Panic-stricken, she ran to the concierge, Madame Ledoit, who had a spare set of keys. When they went into the apartment, they found Suzanne collapsed on a chair, unable to speak or move. She had had another stroke. Madame Ledoit called the doctor and Suzanne was rushed to hospital. There she stayed, in a partial coma, until February 1956, when she was taken home to die on February 8³⁵, with her sister, her two nephews³⁶ and Paulette.

At the last minute, Paulette was wheeled to a neighbor’s apartment so that she would not have to witness her mother’s final moments. However, she had already seen too much to avoid being permanently affected.

Suzanne is buried in the Jewish section of the Bagneux cemetery, in a plot reserved for a Bukovinian nonprofit organization, which offered a final resting place for her.

Paulette had just turned 14 when her mother died. Maurice was named as her legal guardian. Her parents’ friends, Mr. and Madame Wachtel, took care of her so that she could finish her school year at the girls’ school on rue de Clignancourt. With the help of their daughter, Denise, who was a student at the time, she passed her primary school certificate.

The following year, Paulette was placed in an OSE home in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. She continued her studies, with some difficulty, until she was 18 years old, at which time the OSE offered her a position as an au pair girl in England. She agreed to this and found herself in a very orthodox Jewish family with 3 small children to take care of, as well as helping with the housework and cooking. The family was very kind but there was a lot to do and Paulette was not best pleased. However, as there was no possibility of her finding anywhere to stay in Paris, she nevertheless asked to stay on for another year.

At the end of her contract, she returned to Paris where she found an unexciting job because she spoke English. She then returned to live at 42 rue de Clignancourt, where she lived with Henri, Maurice and Maurice’s girlfriend in a somewhat tense atmosphere. Shortly afterwards, she met her future husband, and married him a year later.

The rest of the story is a matter for the Lauer children and it is not appropriate to discuss it here.

The past will have left its mark on all of them one way or another, according to the age at which they were confronted with the loss of their father, their mother’s death and their how isolated they felt as they were growing up.

The three boys have remained very close all their lives. Maurice, walled up in silence, even more so now that a stroke prevents him from expressing himself, has always refused to talk about the past, even with his brothers.

Henri, the youngest and therefore the one who could least express what he felt during the war, lived his whole life in Elie’s wake, still working with him at 80 years old.

Elie and Paulette have both taken life in their stride; they ventured out, traveled and took on the world. They have both been married twice, and have children and grandchildren.

Elie has managed to nurture an amazing love of life. He admits that he did not realize the danger they were in, and did not see that his mother was sick.

Paulette seems to have been more affected than her brother(s) by all her misfortunes and the solitude she experienced in her youth. There is an underlying sadness in her that is not apparent in Elie.

Footnotes

1 See the Book Jews from Suceava/Suczawa (Shotz) and surrounding communities: http://shotzer.com/zope/home/en/1/surround_he/ .

2 According to his deportation card kept in the Arolsen Archives, https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/archive/4545645/?p=1&s=LAUER%20JOSEF&doc_id=4545646

3 The JEWISHGEN ROMANIAN DATABASE, Bukovina birth records. https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/

4 This I. LAUER is a family member who is yet to be researched

5 Jewish Registry Office of Cernauti, marriage record (volume XV, page 298, order number: 29).

6 According to the marriage certificate of Joseph and Suzanne, reproduced in French.

7 According to a file from the Prefecture of Police dated March 22, 1952.

8 Rosa born in 1901, Benesch born in 1898. He was also a tailor.

9 Did they leave Romania at the same time as the Lauer family? This has yet to be researched.

10 Without the Auerbachs, who must therefore have moved house.

11 This raises the question of the children’s nationality. According to Elie, they were declared “stateless” at birth and then naturalized as French citizens at their father’s request. Before 1940, the only requirement for naturalization was to have resided in France for three years. However, in 1940, the Vichy government revised (and in some cases abolished, especially for Jews) all naturalizations granted since 1927. In 1945, de Gaulle abolished the Vichy laws. French citizenship was then granted in priority to foreigners who had been involved in the Resistance.

12 The historian Laurence Klejman informed me that when someone was born in a hospital, it was never mentioned on the declaration of civil status.

13 Did they leave Romania at the same time as the Lauer family? This has yet to be researched.

14 In 1951, the janitor of the building, Madame Ledoit, testified in writing that Josef and Suzanne were indeed living there in 1939.

15 Probably at the Lariboisière hospital – this needs to be verified.

16 The Lariboisière Hospital was at that time exclusively reserved for the German troops who were occupying Paris.

17 In the Paris city registry, there is a Charles Auerbach, born on November 18, 1931 in the 12th district of Paris, as was his twin sister, Gisa who died on February 26, 1932. Charles died on January 8, 2010 in Montluçon, in the Allier department of France.

18 A Désirée Chouippe, born in 1864 in Ravigny, in the Mayenne department of France, is mentioned in the 1936 census as living in Cuissai with an infant in her care.

19 This Madame Long is not mentioned in either the 1936 or 1946 census as living on rue Meslay. Paulette Lauer tried in vain to find her after the war, because she would have liked her to be including in the list of the “Righteous among the Nations”, but without first name or date of birth, it is almost impossible.

20 According to Laurence Klejman, he probably spent time at the police department in the rue du Colisée neighborhood, as was the norm, before being transferred to Drancy on the 20th.

21 Shoah Memorial: http://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/

22 See the website https://convoi77.org/

23 He was also responsible for the deportations from Nice, including Simone Veil’s family.

24 Wikipedia article about Convoy 77

25 These records can be viewed on the Arolsen Archives website: https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/archive/. They are unfortunately difficult to read due to their poor condition.

26 http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/shh/ose/ose.htm

27 Might it be possible to find out who he was?

28 “After the Liberation, about forty Jewish children, whose parents had been deported, were taken in by the Oeuvre de Secours à l’Enfance (Children’s Aid Society), which had rented the castle.” Source: Wikipedia

29 Unlike Elie Wiesel, who was in Buchenwald at the same time but did return home: https://www.ose-france.org/2016/07/lhistoire-delie-wiesel-avec-lose-par-katy-hazan-historienne/

30 The hospital is still in operation and, having become a seawater treatment facility, now specializes in the care of severely disabled adult patients with rare neurological and endocrinological diseases.

31 Probably at the Calot Institute, which specialized in orthopedic surgery. The children who could not be diagnosed during the war, were sent to Berck to be treated for scoliosis with significant distortion.

32 n°42 HA 31768.

33 https://www.memoiredeshommes.sga.defense.gouv.fr/fr/article.php?larub=227&titre=engages-volontaires-etrangers-en-1939-1940. There is indeed a Joseph LAUER but it is a different one, born on February 9, 1907 in Courlin in Romania. He was drafted as a military nurse.

34 This passage is a transcription of Paulette’s recollection of events.

35 Archives of the 18th district of Paris, act n°481, view 10/31.

36 In February 1956, the Auerbach family had not yet left France for Israel.

Français

Français Polski

Polski