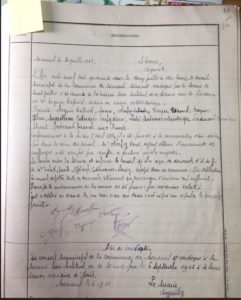

Joseph TABAK

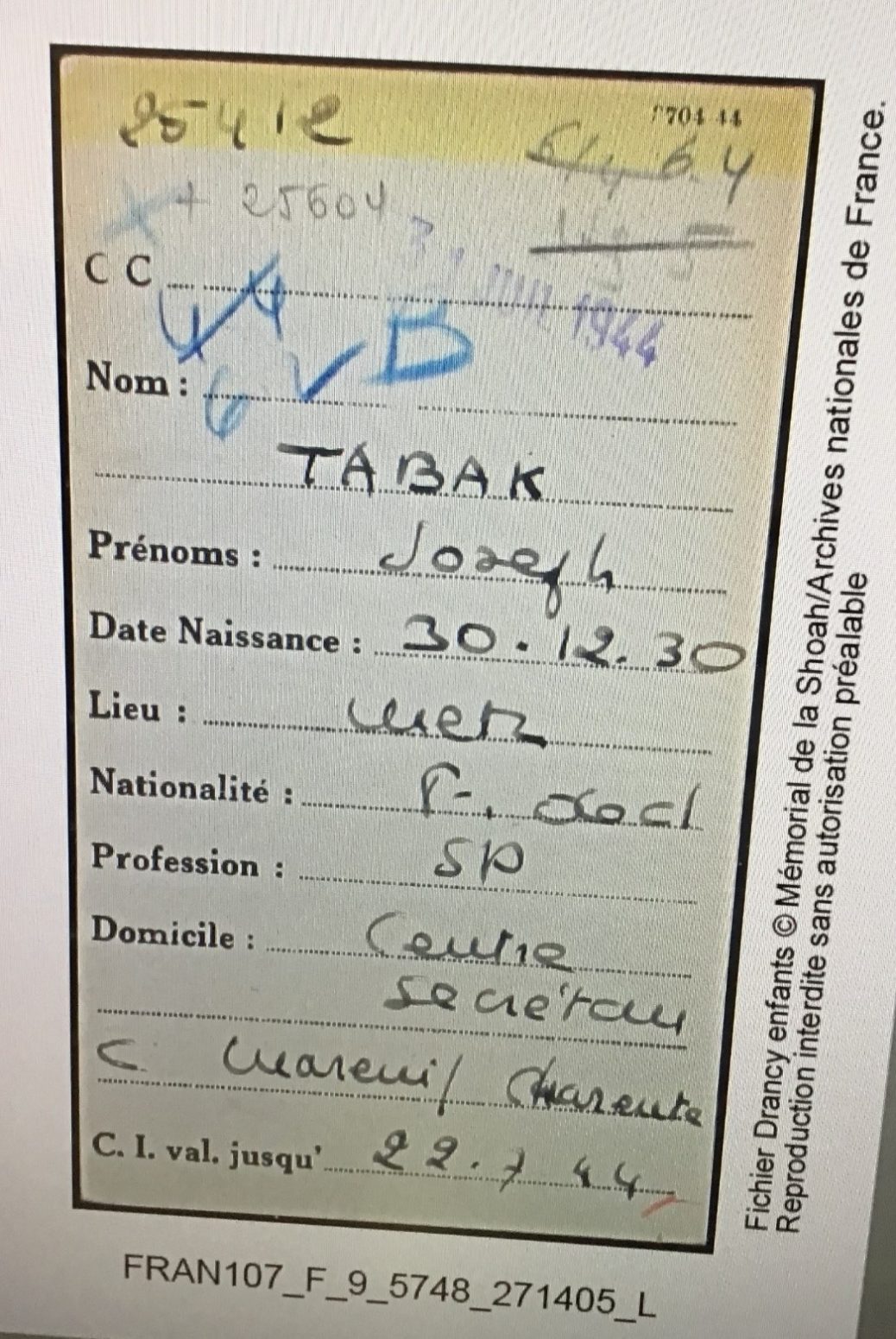

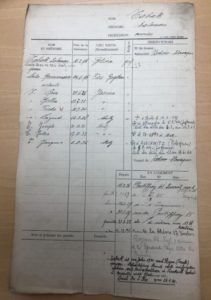

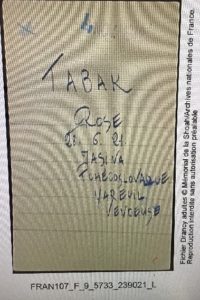

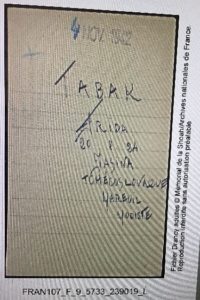

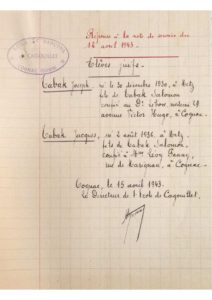

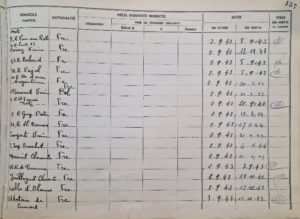

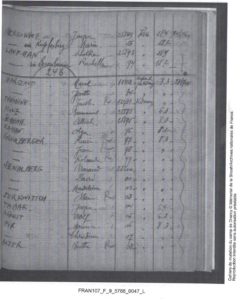

Joseph Tabak’s interment card from Drancy camp. (Shoah Memorial)

We would be delighted if you would visit the online exhibition created by the final year students of class 4 about the maternal family of the Dembicer and Tabak children, and the analysis of Holocaust denial carried out with the help of our philosophy teacher, Vincent Geny.

You can also watch the opening ceremony of the exhibition presented at the high school on May 25, 2023.

Likewise, you can watch the presentation made to the Strasbourg regional council on May 16, 2023 by the final-year students who went on a study trip to Auschwitz.

After much research, we have been unable to find a photo of Joseph Tabak. We are therefore showing a copy of his Drancy internment card, which sums up his short life.

“Insubordination in breach of the law on army recruitment in peacetime”

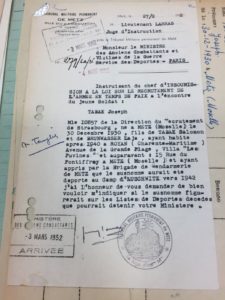

To begin our investigation, we turned to Joseph Tabak’s military record, which was drawn up between 1952 and 1961, when the army was trying to locate him in order to carry out his military service.

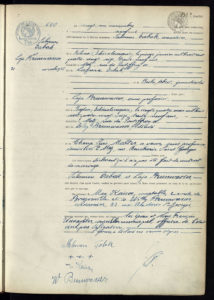

Letter from the military court in Metz to the Deported Persons Department of the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs in Metz, dated February 27, 1952, attempting to verify that Joseph had indeed been deported. (Defense Historical Service archives

Joseph Tabak was investigated for failing to enlist, to appear at the conseil de révision (review board) or to do his military service. He was accused of “Insubordination in breach of the law on army recruitment in peacetime” meaning that he did not appear for military service and was regarded as a deserter. The investigation established that he had been interned in Drancy camp and deported to Auschwitz in July 1944. In 1961, the Metz High Court ruled that Jacques Tabak had died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz.

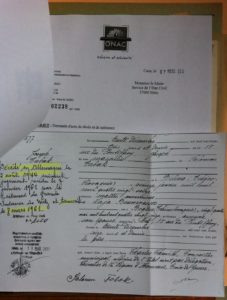

Copy of Joseph Tabak’s birth certificate, with a note of his date of death added in the margin in 1961. This copy was sent to the National Veterans’ Office in 2011 so that Joseph could be acknowledged to have “died during deportation.”

(Defense Historical Service archives)

With the help of numerous records kindly provided by Julia Ghisalberti, Jacques Tabak’s second cousin, we continued our investigation in an attempt to gain a better understanding of his brief existence.

Life in Metz prior to 1939

Joseph Tabak was born into a Czechoslovakian family that moved to France in 1926, at the same time as his mother’s parents and her siblings. According to a 1973 survey by the Jewish aid organization United HIAS Service, his father, Salomon, was living and working in Paris in 1923-24, while his wife and daughters were still living in Jasina, Czechoslovakia. Joseph was born on December, 1930 at the family home at 15 rue du Pontiffroy in Metz. He was the fifth child in the family. The three girls, Rose, Berthe and Frieda, were born in Czechoslovakia while the four boys were born in Metz. Two of them died at a very young age: Lazard (1926-1927) and Jules (1932-1933). Of all his brothers, Joseph knew Jacques, who was born in 1936, best.

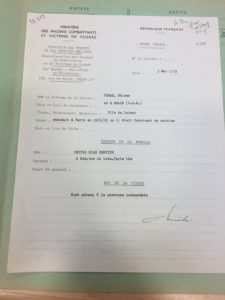

Letter dated May 3, 1973 from the Ministry of Veterans Affairs to the President of the United HIAS Service.

(Defense Historical Service archives).

Salomon Tabak’s residence record.

(Metz municipal archives)

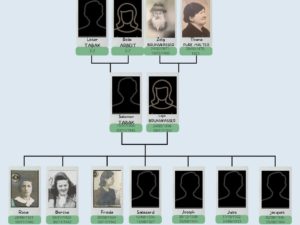

We have put together Joseph Tabak’s family tree, but other than two passport photos of Rosa and Frida, which are included in their in foreign worker card renewal applications, held in the Charente Maritime departmental archives, and a group photo taken at Mareuil in Charente 1942, we have no photos of the Tabak family.

L’arbre généalogique de la famille de Joseph Tabak

L’arbre généalogique de la famille de Joseph Tabak

Jacques’ father, Salomon Tabak, was born on January 15, 1896 in Bilina, and worked as a carpenter and cabinetmaker. On November 21, 1935, he married Laja or Léa Brunwasser, who was born on May 24, 1896 in Bogdan, at the Metz town hall. The couple already had four children at the time. It is likely that they had been married previously in a religious ceremony, but that the marriage was not officially recognized by the French authorities. Léa signed the marriage certificate with crosses, since she was unable to write. The family lived at various addresses in the Pontifroy district, a Jewish quarter of Metz. In 1935, they moved to 17 rue de la Chèvre. Salomon’s workshop was on rue du Grand Wad.

Léa and Salomon Tabak’s marriage certificate.

(Metz municipal archives)

The apartment building at 17 rue de la Chèvre in 2022.

(Photo taken by Antonin, Nina, Romane and Théo)

According to the 1940 census of Jews in Royan, Rose and Berthe (the two elder daughters) were shop assistants, while Frieda was a milliner, or hat-maker. Records relating to the renewal of work permits for foreign workers, also held in the Charente Maritime departmental archives, reveal that while in Metz, Rose worked as a sales assistant for Mr. or Mrs. Vagner on rue du Petit-Paris, and Frieda was an apprentice milliner with Mrs. Maria Steffenboer on rue du Palais. Prior to this, we know that they went to the Georges de la Tour high school for girls in Metz.

Census of Jewish refugees in Royan in 1940.

(Charente Maritime departmental archives)

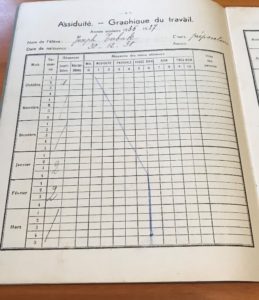

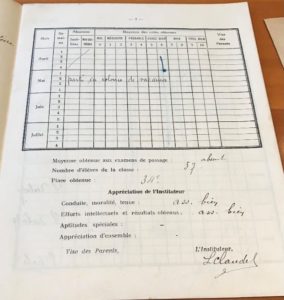

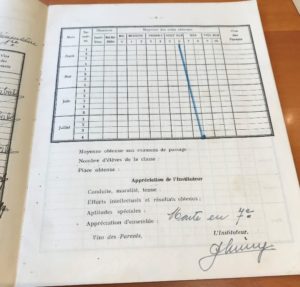

We have no photographs of Joseph, unfortunately. However, our fellow students at the Fabert high school in Metz and their teacher, Ms. Boelle, found some of his school records at the Moselle departmental archives, dating from his time at the Metz preparatory school on rue Chambière. These records give us an insight into his personality. They cover the school years 1936-1937 and 1937-1938, when Joseph was in preschool and first grade. They include work charts and a school report. We note that he stopped going to classes in May 1937, when he went to summer camp.

We see that Joseph is a fairly average pupil in all subjects, but was making steady progress. At the beginning of the first year of elementary school, his performance was deemed to be mediocre. At the end of the year, he was considered fairly good, and then good a year later. He was more inclined towards literature than science, scoring only 4/10 in mathematics in July 1938, but 9/10 in spelling. He was a sloppy student, with low marks for handwriting and drawing. He did not work very hard: he made little effort in recitation, and his overall mark was only 5/10. He only really appears to have put in any effort from June 1938 onwards. As for his behavior, it appears that this too left much to be desired, as he only scored 6/10. On the other hand, he was by this time said to be a diligent student.

Chart on Joseph Tabak’s work during the 1936-1937 school year.

(Moselle departmental archives)

Chart on Joseph Tabak’s work during the 1937-1938 school year.

(Moselle departmental archives)

Joseph Tabak’s school report, July 1938.

(Moselle departmental archives)

We also know that he had several aunts, uncles and first cousins living nearby. We can assume that he was happy during the first few years of his life. In October 1936, soon after his brother Jacques was born, his parents applied for the two boys to be naturalized as French citizens, in accordance with the French Nationality Act of 1927. Since they were both born in France, the application was successful and the boys became French.

The family’s quiet, comfortable life in Metz was turned upside down, however, when the Second World War began in September 1939.

A family displaced during the war (1939-1942)

-

Gorze, in September 1939

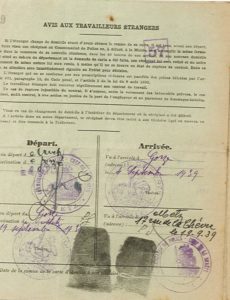

Extract from Rose Tabak’s application to renew her foreign worker’s permit.

(Charente Maritime departmental archives)

From Rose and Frida’s applications to renew their foreign workers’ permits, which are held in the Charente Maritime departmental archives, we see that on September 4, 1939, the day after war was declared, they were in Gorze, a little village on the Meurthe et Moselle border. We presume that the whole family left Metz because they felt that it was too dangerous there. However, it soon became clear during the “Phony War” that there was no actual fighting taking place, so the family moved back to Metz on September 19, 1939.

Extract from the newspaper Le Lorrain dated January 8, 1940.

In early January 1940, the newspaper Le Lorrain reported that Salomon’s bicycle had been stolen. This shows that the family was still living in Metz at the time. This is confirmed by the family’s residence record, which states that they left for Royan in 1940, although it does not give the exact date on which they moved.

-

Royan, in 1940

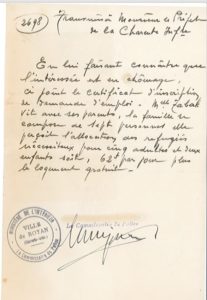

Royan is a seaside resort in the then Charente Inférieure department of France. It became home to a large number of refugees from Lorraine, who stayed in vacation homes that were empty so early in the year. The Tabak family met up with many members of Léa’s family there, including her sister Hélène Sobel, her husband and their four sons, who at one point appear to have been staying with them in a villa called “Les Pivoines” on avenue de la Grande Plage. Her other sister, Rose Dembicer and her children Cécile et Simon were also there. It was Salomon, in fact, who completed the census form for Rose, as her husband was fighting on the front line. Rose Tabak’s application to renew her foreign worker’s permit states that she was unemployed, that the family was destitute, and that she was receiving a refugees’ allowance of 62 francs a day as well as free accommodation.

Extract from Rose Tabak’s application to renew her foreign worker’s permit.

(Charente Maritime departmental archives)

The family stayed in Royan until November 1940, when the German occupying forces banned Jews from the Atlantic seaboard. The family was then sent to Mareuil in the Charente department.

-

Mareuil, from late 1940 to October 1942

Mareuil is a little village to which ten Jewish families, including a total of twenty-seven people, were sent at the end of 1940. The Tabak family moved into a small house. We called the principal of the local elementary school, who confirmed that the boys had indeed attended the village school, but that the records had since been lost.

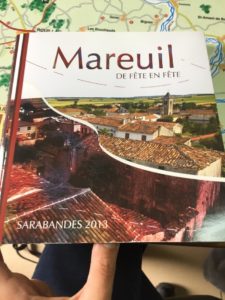

The book Mareuil de fête en fête (Mareuil from festival to festival), which is based on Raymond Troussard’s book Les chemins pour l’enfer (Pathways to hell) reveals that the Tabak family was well integrated into village life, as it includes photos of the three girls at festivals and weddings. These are the only photos of the three sisters. It also says that they worked in the fields, as did other young people of their age. When Julia Ghisalberti visited the village in 2018, she was surprised to find that the Tabak family was still very much alive in local people’s memories. She even found out that Berthe had a boyfriend, Robert Raby, who never got over losing her.

The cover and page 18 of the book Mareuil de fête en fête, published by Sarabande, 2013.

Living conditions in the village must have been quite tough, given that in July 1942, the minutes of the local council meeting mention that the families’ request for free medical care had been turned down. Nevertheless, Salomon Tabak was granted 45 francs to cover some of his medical expenses.

Extract from the minutes of the Mareuil council meeting on July 3, 1942.

(Mareuil town hall)

The family’s rural life came to an abrupt end on October 8, 1942, however, when five members of the family were arrested.

A family torn apart (October 1942 – July 1944)

-

The round-up of the Tabak parents and their daughters on October 8, 1942.

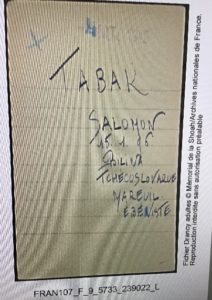

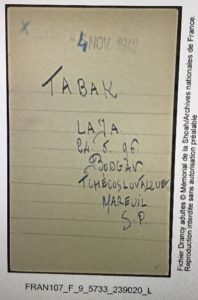

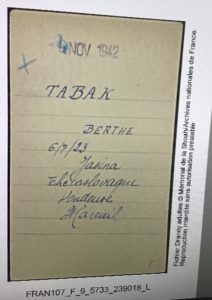

On the night of October 8-9, 1942, 422 Jews were rounded up from all over the occupied Charente and Dordogne departments and taken to the Philharmonic Hall in Angouleme. Among them were Salomon and Léa Tabak and their three daughters Berthe, Frida and Rose. Four policemen from Trouillac arrived on bicycles and arrested them early in the morning. According to eyewitness accounts, the village teacher, Mr. Robert, had his pupils form a guard of honor for the people who were arrested. This is further proof of how well the families had integrated into the village. This was probably the last time Jacques, who was only 6, ever saw his parents and sisters. The Tabaks spent the next 8 days in the Philharmonic Hall. Some of the villagers even went to visit them up until October 15, when they were among the 387 Jews sent to Drancy camp. As their internment records show, all five were deported on November 4, 42 on Convoy 40, and were probably killed as soon as they arrived at Auschwitz.

Drancy camp internment cards for the Tabak parents and their three daughters. The date stamp, November 4, 1942, was the date on which Convoy 40 set off for Auschwitz.

(Shoah Memorial)

-

Joseph and Jacques in Mareuil after the round-up

Unlike their parents and sisters, Joseph and Jacques were not rounded up on October 8, 1942. The village teacher, Mr. Robert, firmly opposed their arrest, arguing in particular that they were French citizens. The same applied to another boy, Justin Wiesel, from Thionville. They were taken in by a local family, the Marolleau family, until they were finally arrested, on an unknown date. Clearly, the children had formed a bond with the other children in the village. Following her visit to Mareuil in 2018, Julia Ghisalberti received a letter explaining that after the children had left, their toys had been found in the house where they had lived, and that the new owners had then decided to wall them in so that they would remain there forever. In 1995, a commemorative plaque in honor of the village’s Jewish families was unveiled, testifying to the respect and affection shown by the people of Mareuil for the families they had sheltered.

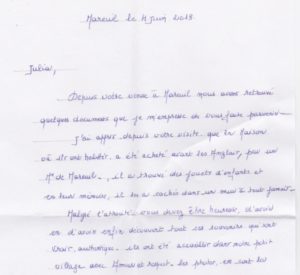

The letter that Julia Ghisalberti received in 2018 after her visit to Mareuil.

The commemorative plaque in Mareuil.

-

Joseph and Jacques in Cognac in the spring of 1943

We next catch up with Joseph and Jacques in March-April 1943 in Cognac, in the Charente department of France. Joseph was placed with Dr. Lebow at 29 avenue Victor Hugo. We have no further details about this doctor. As for Jacques he was placed with Fanny Levy, a French Jew who came from Alsace. On a statement of payments to families who took in children, we see that Fanny Lévy received 1215 francs in March, representing three months’ allowance. Jacques must therefore have been staying with her since January. Although living apart, the two brothers both went to the Cagouillet school, where they were registered as Jewish children in April 1943, following a request from the Prefecture.

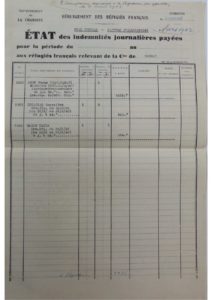

Statement of allowances paid in March 1943 to people housing French refugees in Cognac.

(Cognac municipal archives)

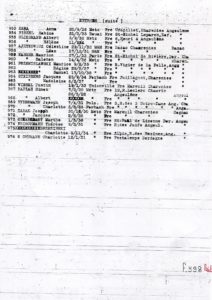

Response from the principal of the Cagouillet school to the census of Jewish pupils enrolled in schools in Charente.

(Cognac municipal archives)

-

Joseph and Jacques in the Lamarck children’s home (June 1943- April 1944)

On June 9, 1943, the two boys were admitted to the Lamarck center, which was near the Sacré Coeur in Paris. It was a children’s home run by the UGIG (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews) which took in children whose parents had been deported. On August 2, 1943, the two brothers were transferred to another UGIF facility, this time in Louveciennes, in the countryside, probably to improve their health. There they were reunited with their first cousins, Cécile and Simon Dembicer, who had been staying there since the summer of 1943. We can only assume that the four children were happy to temporarily rebuild the family ties they had previously enjoyed. They stayed there until September 2, when they were sent back to the Lamarck center.

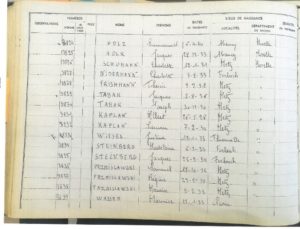

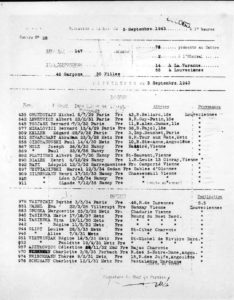

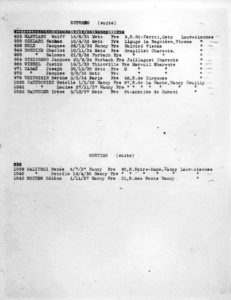

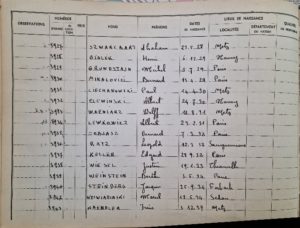

Record of arrivals and departures from the Lamarck center (UGIF center no. 28) for June 9, 1943.

(Shoah Memorial)

Pages from the Lamarck center register.

(Montmartre Jewish center)

Lamarck center record of arrivals and departures on September 5,1943.

(Shoah Memorial)

-

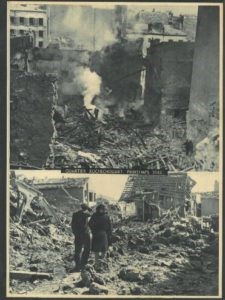

The bombing of the Lamarck center and Joseph’s’ transfer to La Varenne

On April 21, 1944, the Allies carried out a military operation in northern Paris, to the south Plaine Saint-Denis, in order to destroy the La Chapelle marshalling yard. As a result, the Lamarck center was partially destroyed, and the children living there, including Jacques and Joseph Tabak, had to be moved to other UGIF homes. The brothers were split up, probably due to the age difference between them. Jacques, who was 7, was sent to a home in la Varenne, outside Paris, while Joseph, who was 13, while Joseph was transferred to the Secrétan home, which was part of the Hirsch school (the oldest Jewish school in Paris) where he was to be educated. He was surrounded by friends of the same age, but was probably worried and upset that his little brother was no longer with him.

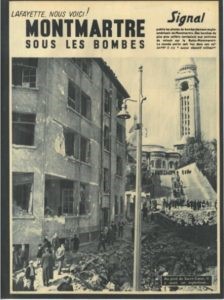

Pages from the Signal, a Nazi propaganda publication from the spring of 1944. Note the cynical tone used to criticize the Allies for their vicious attack on the Jewish orphanage, and how they include a picture of a bed.

(Montmartre Jewish center archives)

Pages from the Lamarck center register.

(Montmartre Jewish center)

On the night of July 22 to 23, 1944, Joseph’s life was turned upside down yet again.

July 1944: the arrest and deportation

On July 20, 1944, some German officers attempted to assassinate Hitler. Their plan failed, but it was enough to cause a great deal of confusion, which proved fatal for the children in the UGIF centers in and around Paris. Between July 22 and 24, 1944, Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, who was fanatic about the “Final Solution”, carried out a roundup of all the homes, arresting even the youngest children and the French citizens, with the aim of cramming as many Jews as possible into what he knew would be the last convoy to Auschwitz.

Les 78 orphans in the Secrétan home were arrested on the 22nd, early in the morning. Having been rudely awakened, the children were hurried onto buses and driven to Drancy. Joseph was reunited with his cousins, Cécile et Simon Dembicer, who were arrested on in Louveciennes on the same day. The following day, his brother Jacques arrived. They were both assigned to room 4, on stairwell 6. The four children were all deported to Auschwitz on July 31, and were most likely killed in the gas chambers soon after they arrived.

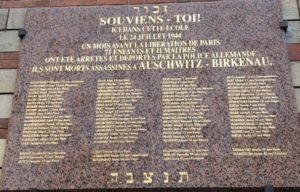

Plaque in memory of the victims of the round-up in Secrétan.

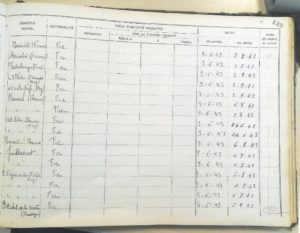

A page from the Drancy transfer log.

(Shoah Memorial)

Français

Français Polski

Polski