Léon GREITZER

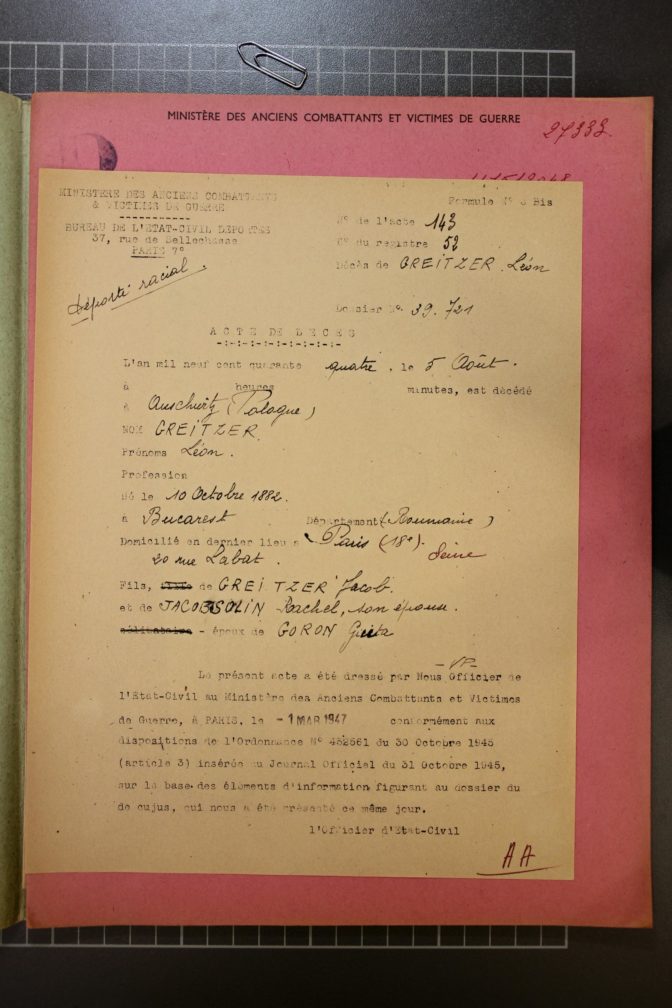

As an introductory image, we have decided to use Léon’s death certificate, since no photos of him or other personal documents are available.

Fruit and vegetable merchants’ carts at the corner of rue Poissonniers, rue Marcadet and rue Labat, in the early 20th century

Nothing remains of Leon and Guita Greitzer. Not a single photo nor even one memory of them has passed from their son to their granddaughter. There are just a few snippets of their lives.

The few records we found tell us little more. We know that their journey from Eastern Europe to Paris was a story of emigration and resettlement in another country. Then came the war and their deportation.

Leon was born on October 10, 1882 in Bucharest, Romania. His parents were Jacob Greitzer and Rachel Jacobsohn. His mother was still alive in 1926. We know that he had at least one brother, who was called Salomon. In his application for French citizenship by naturalization, Salomon is described as a “commercial traveler”. According to his great-niece, he was a grain merchant. We only know about one aspect of Léon’s youth! The records in Léon Greitzer’s application for naturalization tell us a little about his state of health: he was exempt from military service in Romania because he was paralyzed in one leg due to tuberculosis of the bone. As a result, he was not able to fight in the First World War while he was living in France and it was for this reason that his first application for French citizenship was denied in 1919. When he reapplied in 1926, the authorities suggested that he wait “until his son was called up for military service”. His son, Jacob, was 14 years old at the time.

From their naturalization certificate, we know that Léon and Guita Greitzer arrived in France in 1905. Why they decided to emigrate, we do not know. We also do not know where they met. Either way, Léon applied for French citizenship for the first time in 1919. He had to wait until his second application in 1926 for it to be granted. At that time, wives had to be included in their husband’s application and Léon’s naturalization records tell us nothing about Guita, other than that she was unable to sign her name.

We do not know where, when, or how they first met, but we know that they started a family and lived all their lives in the same neighborhood; Montmartre, in the north of Paris. Their son went to the local school there, according to his daughter (Leon and Guita’s granddaughter). They lived for more than twenty years at 20 rue Labat, in the 18th district of Paris, in the Clignancourt area near Boulevard Barbès. At 20 rue Labat, the Greitzers lived in a small apartment, which their son continued to live in after the war. Léon and Guita’s granddaughter grew up in this apartment and she described it to us as a very small two-room apartment on the third floor to the left, with the toilets on the landing, with one of the rooms overlooking the street and the other the courtyard.

Rue Labat and the surrounding area at the beginning of the 20th century

Their son Jacob was born at 6:30 a.m. on January 13, 1912 at 83, Boulevard de l’Hôpital.

Léon was twenty-nine years old at the time, and Guita was thirty. However, Jacob and Guita did not get married until seven years later, which means that in 1912, when Jacob was born, they were not husband and wife. Nevertheless, his birth certificate states that his parents were married, probably for the sake of respectability. In the margin, it is noted that Léon acknowledged that Jacob was his son and Jacob thus became a legitimate child on the day of his parents’ wedding, in 1917.

Jacob Greitzer’s birth certificate

Guita and Léon got married on July 5, 1917, at 11:30 a.m., in the town hall of the 18th district of Paris. The deputy mayor of the 18th district, Jean-Henri Mayoux, presided over the ceremony. Their witnesses were Baptiste Grimberg (44 years old, a tinsmith), Maurice Ségall (54 years old, a fruit seller), Louise Baudet or Bodet (64 years old, a janitor at 20 rue Labat, where the Greitzer family then lived) and Lucie Bourdier (64 years old, a housewife who lived at the same address): they were all very ordinary people.

Goron Greitzer’s marriage certificate

Depending on the source in question (civil status records, citizenship documents, etc.), the Greitzers had two/three different occupations: in 1919 Léon was an antique dealer and Guita was not working, whereas in 1926 they were both fruit and vegetable merchants, selling their wares from a small handcart. But it is easy to imagine what was meant by an antiques dealer: just a few old objects on a handcart, rather than a store full of beautiful antiques, but Léon held a permit for his little business. On his citizenship application, Léon stated that in 1919, he and Guita earned about 10 francs a day selling groceries, and their rent was 300 French francs a year. By 1926, although they were then making 20 francs a day, their rent had also almost doubled to 520 francs a year. Lastly, after the war, when their son submitted a request to have his parents recognized as having been political deportees, Léon was said to be a bookbinder.

Between themselves, one of them Romanian and the other Russian, they spoke in Yiddish, so their granddaughter told us.

When the family moved to 20, rue Labat in April 1914, Jacob was 2 years old. His daughter confirmed that Jacob had studied at the same elementary school as her, except that at the time, the schools were not co-educational so while she went to the girls’ school, he went to the boys’ school. According to her, this was the Clignancourt school, which is now the Roland Dorgelès secondary school. The school was at 63, rue de Clignancourt, just five minutes from the building where the Greitzer family lived at 20, rue Labat, so it makes sense that Jacob would have gone there, yet when we went to the Paris Archives and looked through all the school registers for the years in which Jacob would have been the right age to go there, we could not find his name anywhere. We then checked the register of another school, eight minutes away from 20, rue Labat, but again found no sign of him. However, at the time when Jacob would have been in school (1918 – 1923), education was of course compulsory (in addition to being secular and cost-free). What’s more, Jacob’s daughter is quite sure that he studied in this school. It’s a total mystery! How come there is no trace of Jacob at elementary school?

There is no trace whatsoever of them during the 1920s and 1930s. Their son grew up, became a hairdresser, and when the war broke out, he may have been working in Saint-Denis.

A hair salon on rue des Poissonniers

Then came the war, and based on what we have learned, we imagine that Leon and Guita Greitzer may have guessed what was in store for them.

Their own son, Jacob, was held for two and a half months in Drancy and was in danger of being deported: his physical condition when he was released bore witness to what was happening there. In fact, from August 20 through 24, 1941, a major round-up took place in Paris. It began in the 11th district of Paris on August 20, then continued in the 10th, 18th, 19th and 20th districts on August 21. In the following days, the round-up spread to the other districts. Jewish men, both French and foreign, between the ages of 18 and 50 were arrested by the French police and the Feldgendarmerie. Jacob was arrested in the street on August 21.

In total, 4,232 people were arrested. Living conditions in Drancy deteriorated drastically, but two months after the roundup, in November 1941, the camp commander, who was also in charge the Paris Gestapo, Theodor Dannecker (he was the one who organized the Vel d’Hiv roundup), left to take a break. In doing so, he left the camp unsupervised. After that, the camp doctors arranged for the sickest and weakest to leave the camp and then had to release 800 people and allow families to send in parcels. As a result, almost 1,200 internees were released, including Jacob.

Jacob was released from Drancy in November 1941

During his time in Drancy, Jacob had around 45 pounds, because he had only had one bowl of soup to eat each day! When his parents saw the state of him when he came out of Drancy, they were terrified that he would be found and imprisoned again, so they arranged for him to leave for the Free Zone. He crossed the demarcation line together with a nurse and then headed for the Vercours mountains, where he joined a group of resistance fighters. His code name in the Resistance was Tino.

At the same time, the Greitzer’s neighbors were being arrested on after another, so they must have known they were in danger. They could not deny what was happening, given the number of arrests taking place: At 20 rue Labat alone, 21 people were arrested. There were more arrests in this building than in any other on the street (followed by No. 3, where there were 11 arrests and No. 73, where there were also 11). 5 people from the building were arrested during the Vel d’Hiv round-up, along with 17 from the rest of rue Labat. In fact, most people, such as the Greitzers, escaped without our knowing why or how. But let’s not forget that the Greitzers knew from their son Jacob what Drancy was like. These five people, five neighbors, were, first of all, Rachele Gryner, a 35-year-old Polish seamstress who was deported on Convoy 11 in July 1942. Then there were Perla and Salomon Rojter, who, using the first names of Paulette and Bernard, had lived there since 1936. He worked as a mechanic. They were rounded up in July, locked up in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp and deported separately on Convoys 15 and 22. Their son Charles, who was born in 1932, is not on the list of those deported; he was no doubt a hidden child. Lastly, there were Charlotte and Tauby Sztanberg, who were also arrested during the Vel d’Hiv roundup and also spent time at Beaune la Rolande before being deported on Convoy 15.

20 Romanian Jews were arrested on rue Labat in September 1942, including 4 at No. 20 alone. The Greitzer family probably witnessed the arrests: first of all, there was Suza Leibovici, aged 34 and married, a Romanian Jew, who was deported on Convoy 37 on September 22, 1942. Next were Elsa, Monique and Spirtzea Ghermanski, Romanian citizens originally from Kichinev, who were rounded up on September 24, 1942 and deported the very next day.

However, it was the arrest of Rachel (or Rokla) Ganelesh in particular that must have upset Léon and Guita the most: she was a 71-year-old Russian woman who had been living at 20, rue Labat since at least 1926. She lived alone and, like Léon, was a second-hand dealer, so it is quite likely that they worked together. She was arrested in November 1942 and deported on Convoy 45.

It was last convoy however, Convoy 77, that accounted for the highest number of arrests: 13 residents of rue Labat were arrested in June 1944 and subsequently deported, including 9 from No. 20 alone. Léon and Guita were sent to Auschwitz with their neighbors, perhaps even their friends, some of whom were very young and others who, like them, were older. In their convoy, number 77, there was, for example, a woman who appears on the lists as Sarah Bouaniche but who in reality was called Suzanne. She was 27 years old, born in Paris in 1917, and had lived in the building since at least 1936. Suzanne survived: eventually sent to the Kratsau camp in Czechoslovakia, she was liberated by the Russians. Sura Glatzleider, a 57-year-old Polish woman who did not work, and her daughter Adèle, a 24-year-old shorthand typist, were long-time residents of the building (they too had lived there since at least 1926), as were their neighbors Isaac and Thérèse Meistelman. Isaac was already in the building in 1926. Originally from Russia, he married Thérèse Brodsky and they moved to 84, rue Daurémont in the 18th district, but later returned to rue Labat. Isaac was an upholsterer. There was also a certain Russic (or Rosa) Meistelman from 20, rue Labat, a shorthand typist, who was deported on Convoy 11 on July 27, 1942 following the Vel d’Hiv round-up. Could she have been Isaac’s sister, born in Russia in 1913? Another neighbor, a little older than the Greitzers, Abraham Santer, a 74-year-old Polish laborer, was deported on Convoy 77, as was Syria Scherman, a Russian woman born in 1879. Her family was already living in the building in 1936, although she herself was not.

Everyone in the building, including Léon and Guita, was arrested by the Gestapo on July 1, 1944, in a “home” raid. The janitor of the building, Madame Turri, testified to this after the war. They were interned for one long month in Drancy, since convoy No. 77 only left on July 31. In Auschwitz, when they got off the train, the deportees were sorted into two groups: the first was sent to the gas chamber, and the other to work (in factories for example). Leon and Guita were 61 and 65 years old, so there is no doubt that they were in the first group and were killed immediately. The date of their death was determined to be August 5, 1944, in Auschwitz.

Information about the arrest, taken from an application for the status of “political deportee”

When Jacob returned to Paris after the Liberation, he went back to his parents’ apartment at 20, rue Labat; all he found there was some crockery that the neighbors had kept and someone had to lend him a mattress so that he could move back in.

Sources

- Photo 1: Fruit and vegetable merchants’ carts at the corner of rue Poissonniers, rue Marcadet and rue Labat, in the early 20th century www.cparama.com

- Photos 2 to 10: Rue Labat and the surrounding area at the beginning of the 20th century, www.cparama.com

- Photo 11: Jacob Greitzer’s birth certificate, Seine Departmental Archives

- Photo 12: Goron Greitzer’s marriage certificate, Seine Departmental Archives

- Photo 13: A hair salon on rue des Poissonniers, www.cparama.com

- Photo 14: Jacob was released from Drancy in November 1941, Michèle Hazan’s family archives

- DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service) dossier reference 21 P 458 493

- Censuses of the population of Paris 1926, 1931 and 1936, Paris Archives, image D2M8 294 (for 1926), D2M8 445 (for 1931) and D2M8 672 (for 1936).

- School records, image 2859W 1 to 28, Paris Archives

This biography has been made into a presentation on the Prezi website:

https://prezi.com/view/breFikB7Vu88OcljqNTy/

This research is based on documents contained in a DAVCC file on Leon Greitzer file and in his citizenship application dossier, as well as on the testimony of his granddaughter, Michèle Hazan, collected between December 2021 and April 2022.

The project was carried out between November 2021 and June 2022 by Alice Andrade Poisson-Quinton, Mathilde Beauvais-Loheac, Lou-Ann Berthier-Pham, Maya Bonnot, Gavroche Brétaudeau, Juliette Claudepierre, Adèle Collet, Diane Dongier, Anatole Labourey, Agathe Lescuyer, Marion Mancel and Nils Montaignac, 9th grade students at the Pierre Alviset middle school in Paris under the guidance of Catherine Darley, their history and geography teacher.

Français

Français Polski

Polski