Meier SILBERMANN

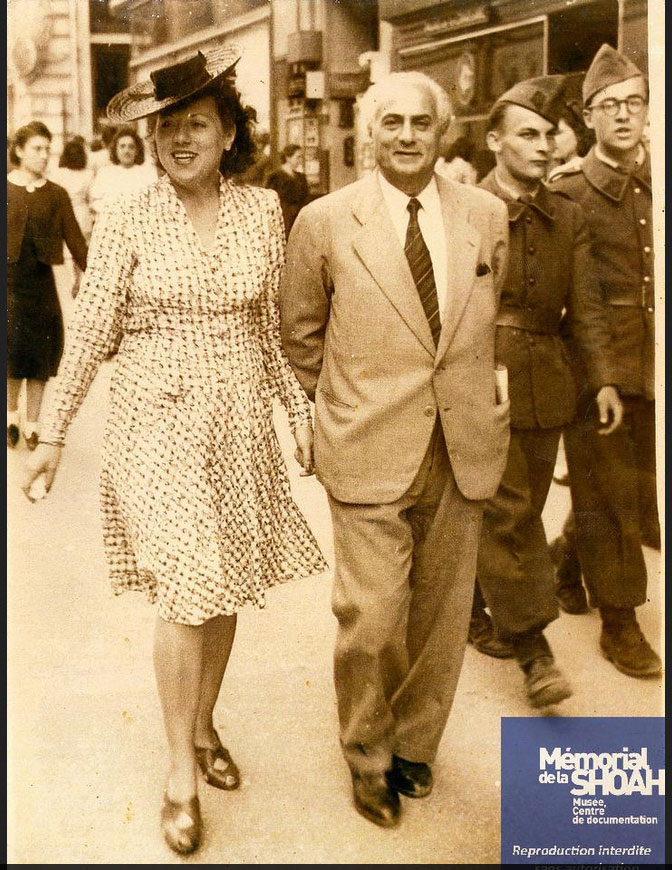

Photo of Meier/Maxime (on the right) and his daughter Ida (on the left), during the war. Source: the Shoah Memorial in Paris

Maxime Silbermann, who was also known as Meier Löb Silbermann, (the spelling differs between documents: Meier, Mayer, Meyer) was born, according to the information we have, either on October 17, 1879, according to an official record, or on September 16, 1879 (as mentioned in a letter from his daughter Ida, written on October 4, 1945, and in some civil registry records), in Moscow, Russia.

His father was called Abraham Harisch Litmaroff Silbermann and his mother was Iti Abramoff.

A chemical engineer with Russian citizenship, he arrived in France in 1899. At the time, he was considered a “foreigner engaged in an industrial profession”. According to his “card for foreigners engaged in a commercial or industrial profession” he was a “chemical and oil products employee”. This card also served as official proof of identity.

We believe he met his wife, Clara Libermann, who was a Romanian citizen, after he arrived in France. They were married on March 23, 1911. They had a son, Henri, born in Paris on July 7, 1912, and a daughter, Ida, born in Bellerive, in the Allier department of France, on June 3, 1918.

HIs wife Clara died before the war, on December 1, 1937, in Paris.

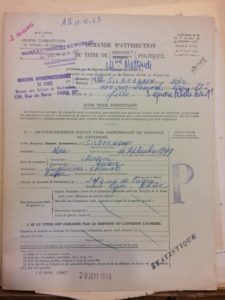

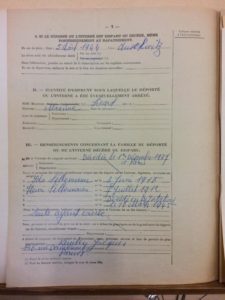

Page 1 of the request for political deportee status

Henri was arrested on July 21, 1944 at Saint Didier du Mont d’Or in the Rhône department of France, under the name Henri Chevalier. He was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 78 on August 11. He died in the Mauthausen camp in Austria on March 18, 1945.

In 1939, according to the records, Meier was living at 28 rue du Château d’Eau in Paris.

On June 28, 1944, Meier, now known as Max, was at his home at 274 rue Créqui in the 7th district of Lyon, together with his daughter Ida, when the Gestapo came to arrest them as a result of a tip-off. They give their names as Maxime and Irène Sicard.

They were taken to the Fort de Montluc, a jail in Lyon, where they stayed from June 28 to July 23, and then transferred to Drancy, where they were held until July 31, the date on which Convoy 77 set off for Auschwitz.

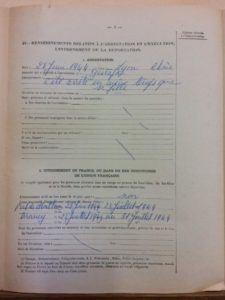

Page 3 of the request for political deportee status: Information about the arrest, how it happened, the internment and the deportation.

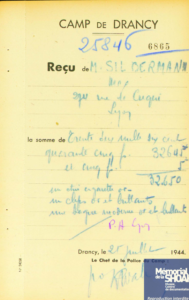

A receipt issued when Max arrived at Drancy camp states that he had on him the sum of 32,650 francs, a gold cigarette case and some jewelry, including a gold and diamond ring.

Receipt from the Drancy camp search logbook. Source: the Shoah Memorial website

Convoy 77, which was one of the last to leave Drancy, took them to Auschwitz. The transport was made up of 986 men and women and 324 children. Over 75% of the deportees were under the age of 50, and 125 were children under the age of 10.

When they arrived in Auschwitz, Max and his daughter were separated as soon as they got off the train; Max was taken away in a truck, as were many other people, while Ida and some of the others were taken into the camp on foot. Each person was given an identification number: Max was number 6865.

Max and all the people with him were killed as soon after they arrived in Auschwitz. The SS only kept people who were fit to work. They put the weak and less able people into trucks without telling them that they were about to be executed in the gas chambers. Max’s official date of death is August 5, 1944.

Page 2 of the request for political deportee status

All this information is available today thanks to his daughter Ida, who survived and sought to find out what had become of her father and brother.

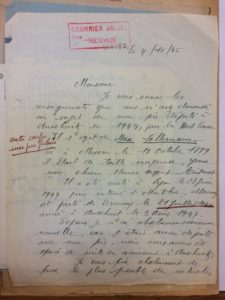

Ida’s letter of October 4, 1945

In her letter of October 4, 1945, Ida describes her father as a man of medium height, with dark eyes and silver-white hair. She then submitted another, more formal request to the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs on July 21, 1949, in which she requested the “correction of the civil status of a “non-returned person”. This led to the issue of Max’s death certificate on October 14. 1949.

His daughter also requested that Max was recognized as having been a “political deportee” (meaning that he was deported for political reasons). As a result, he was awarded compensation of 12,000 francs, posthumously, which Ida, as his heir, was able to claim.

Sources :

- Various records kindly provided by the Convoy 77 project team.

- Photos and search log receipt, the Shoah Memorial website.

Français

Français Polski

Polski