Menahem PINTO

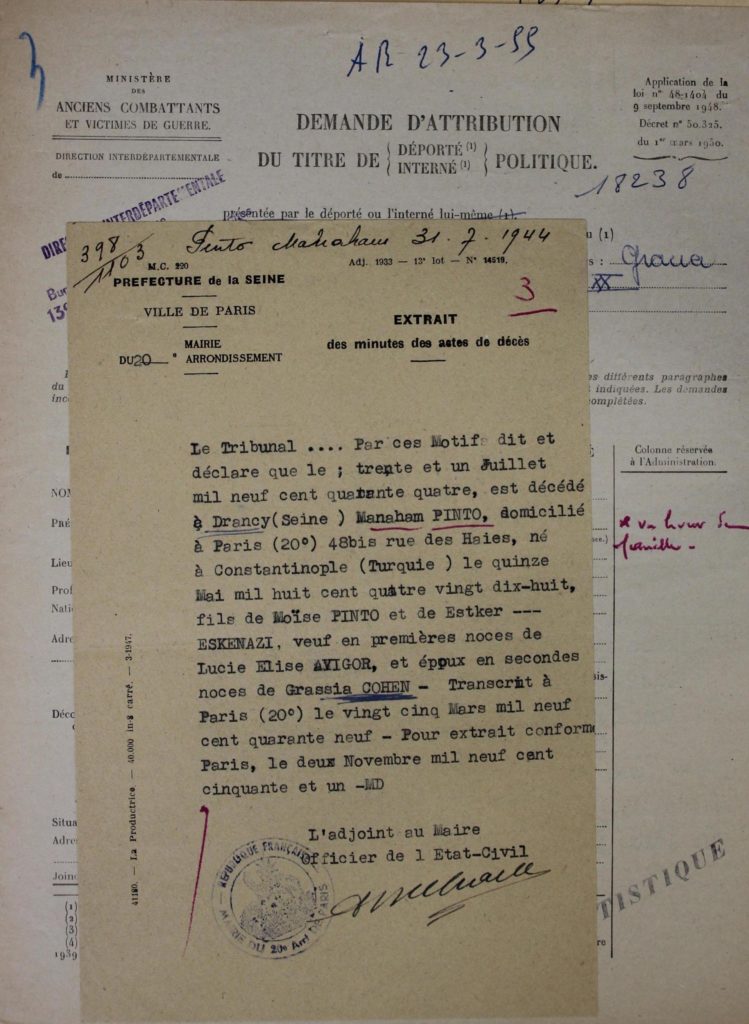

As there are no photographs of Menahem Pinto, we are showing an extract from his death certificate, which mentions his various family relationships. Source: file on PINTO Maurice © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Normandy, ref. 21P 526 044 45636.

A group of 11 9th-grade students from the Pierre Alviset secondary school in Paris undertook to write the biographies of three members of the Pinto family: the father, Menahem, and two of his five children, Esther and Maurice.

The only thing we knew for sure was that they were dead, having been murdered in Auschwitz in early August 1944. We also knew that the mother, sister and two younger brothers of the family were not arrested, and so survived. Esther, who was the oldest of the siblings, was deported when she was just fifteen.

First of all, we had to decide on how best to tell the family’s story, to include the both family members who were deported and those who stayed behind. What was the best way to structure such a narrative?

Rather than write three separate biographies, one for each of the family members who were killed by the Nazis, we decided to chronicle the lives of the entire Pinto family. Spanish-Jews, with their roots in Istanbul and Salonika (Thessaloniki), all of family members were Holocaust victims, either directly or indirectly. In order to do that, the students, all of whom were girls this year, all took up their pens to write a section of “Esther’s diary”. The idea was to write a “personal diary”, in which the students would use their imagination to fill in the gaps in the data. However, using their imaginiation did not mean making things up; everything they wrote was based on the information they had gathered about the Pinto family and their home environment. What follows is the “diary” of the eldest daughter, Esther, in which, after outlining her family background, she describes day-to-day life in occupied Paris.

Catherine Darley

Esther’s diary

Wednesday May 29, 1940

Dear Diary,

Today was my birthday. My parents were very kind, and my mother re-stitched a dress that I really liked but couldn’t wear anymore because I’d grown too big for it. I’m going to be careful where I hang it now, because it’s my favorite and I don’t want the moths to get at it. I tried it on right away! My family wasn’t able to give me anything else because we’re not very well-off, but that’s OK. I was delighted when Jacques, Mathilde, Maurice and Albert gave me a big hug when I woke up, all shouting “Happy birthday!”.

When I got to school, the teacher gave me this notebook. She told me to “keep my diary”, so I’m going to write down all my thoughts in it, and also anything important that happens:

Thursday May 30, 1940

Dear Diary,

First of all, I’m going to introduce you to my family and tell you about our neighborhood, then I’ll write about what’s happening in my life.

My father, Menahem Pinto, comes from Constantinople, in Turkey. He arrived in France on October 7, 1919, long before I was born. He is Turkish, but when he was a boy, the country was called the Ottoman Empire. He says that after the First World War, when it became Turkey, life became difficult for Jews, so he decided to move to France in search of freedom.

This record, dated after Menahem’s death, is included in the application to have him awarded the status of political deportee. It shows the date on which he arrived in France.

Source: PINTO Menahem © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21P 526 044 45636

He’s street vendor now, but he used to be a butcher. He was married before, to a Lucie Avigdor. He doesn’t like to talk about it in front of Mom, but I did my homework and found out that she too came from Constantinople and that she’d also been a street vendor. I didn’t find out until later, but she apparently died in 1928, not long before Dad married Mom. Anyway, never mind, I don’t want to dwell on that too much. So then my father got married again, this time to my mother, Grassia Cohen. If I remember correctly, it was in 1928, about a year before I was born. My parents often talk about their wedding ceremony at the town hall in the 11th district of Paris.

Menahem Pinto and Grassia Cohen’s marriage certificate, dated March 29, 1928, at the town hall in the 11th district of Paris. Only Menahem signed his name, so we assume that Grassia could not read and write at the time. Source: Civil status archives at the Paris departmental archives.

My mother works as a chambermaid. She’s Greek, was born in Salonika and she too is Jewish. She still misses Greece and her parents, Moses and Mazalto Cohen.

I never met my paternal grandparents, Moïse Pinto and Esther Eskenazi, because they died in around 1921, before I was born.

My parents went on to have children of their own. I was their first, in 1929, followed by my sister Mathilde in 1931, my brother Maurice in 1933, Albert in 1935 and the youngest, Jacques, in 1936. We’re a large family, so sometimes it’s hard to get any attention, but we’re very happy. We live at 48 bis de la rue des Haies, in the 20th district of Paris. We moved here in 1935, a few months before Jacques was born. We all go to school every day: Maurice goes to the boys’ school on rue Vitruve, the little ones go to kindergarten at 99 rue des Pyrénées, and Mathilde and I go to the girls’ school right next door, at No. 97.

We sometimes have some free time on Sundays, and my siblings and I play hide-and-seek for hours. Dad buys his supplies from a linen store on rue Sedaine, and we play with the owner’s children. We run round all the passageways and cul-de-sacs in the neighborhood. My best ever hiding place was in the trunk outside the cobbler’s shop on impasse Popincourt.

The streets are buzzing with activity, especially on Saturday mornings, when all the Jews flock to all the stores we have around here. My favorite is the boutique on passage Lisa, and Mom once bought me a dress there because I’d done so well at school.

We sometimes go to the synagogue at 7-9 rue Popincourt, where we meet up with family and friends. They speak Ladino there (a bit like Spanish), just as they do in Salonika, where Mom was born. Our neighborhood is often called the “Oriental Jewish Quarter”, and I know that a lot Jews from Greece and Turkey come here to look for work. That has reminded me of something. Everyone in the neighborhood talks about work contracts, because people need them to get a visa to move to France. Sometimes they start arguing about it all, so I keep out of the way.

At school right now, there’s a lot of talk about war. The Germans are attacking France, which is really scary. I keep wondering what’s going to happen next.

Thursday May 23,1940

Dear Diary,

I walked past the newsstand this morning. As soon as I saw the headlines, I ran home to get 30 centimes to buy the “Paris-Soir” newspaper.

The front page of the Paris Soir newspaper, May 22, 1940. Source: retronews.fr

Oh, this is just awful… The Germans are advancing further and further! I’m scared, they’re gaining ground everywhere, they’ve already taken the towns of Arras and Amiens in the north, and even the Atlantic coast. Are they going to occupy the whole of France?

Tuesday June 11, 1940

Dear Diary,

There was a lot of commotion in the streets yesterday morning. Very early on, around 5 o’clock, Mom woke Maurice, Albert, Jacques, Mathilde and me up. We packed our bags in a matter of minutes, as Mom seemed rushed and really stressed. But when we got down to the street, we could hardly move! We tried to make our way through the hustle and bustle, but we only just made it as far as the Rue de la Réunion, which was completely blocked off! We had to wait in a side street for a long time before we could even get that far. Mom and Dad found a place to sit down and think, away from all the commotion, looking totally bewildered. Then they got up, grabbed our hands and took us home. Mom insisted that I should still go to school today, but when I got there, it was closed.

I didn’t really understand why everyone was running away, but a girlfriend from school explained it to me: people are calling it “the exodus”. It’s happening because of the German invasion. Apparently, they’re bombing some places and machine-gunning people. I told Mom about it when I got home and asked her why we hadn’t left Paris. She told me that panic had got the better of her to begin with, and that’s why she and Dad woke us up so suddenly, but on second thoughts, maybe they’d made up their minds too soon. Besides which, we had no means of transport, and it would have been too dangerous for all seven us to travel far on foot. It worries me that so many people have fled Paris, because I figure they must have been really scared of something to cause such mayhem. But anyway, we’ll see what happens tomorrow.

Saturday June 15, 1940

Dear Diary,

When I got to school this morning, the playground was buzzing. My girlfriends told me that the Germans marched down the Champs-Élysées yesterday and they had drums, tanks and all sorts of military stuff.

Dad told me it’s because they’re so happy to have won the war, but he doesn’t like them because they’re anti-Semitic (he explained that means people who don’t like Jews, in which case I don’t like them either). I don’t get it: you can dislike somebody for any number of reasons, but I don’t see what’s wrong with being Jewish; it’s kind of similar to being Christian or Muslim, isn’t it?

Monday June 17, 1940

Dear Diary,

Earlier today, when I went into the kitchen, the radio was on full volume and my parents were concentrating hard. I’ve never seen them like that in my life. I sat down next to Mom, who scolded me for making so much noise, so I kept quiet and listened. Marshall Pétain was making a speech about how hard it had been to make this decision, but that the fighting had to stop, so he was asking Germany to sign an armistice. I know what an armistice is, because our teacher explained it when we were learning about the 14-18 war. It’s a sort of contract that two warring countries sign, and then they stop fighting. At that point, Mom burst into tears. She cried so hard she looked as if she was about to run out of oxygen, but Dad did nothing to calm her down. He just sat with his arms on the table and a blank look in his eyes. Then they started talking in Ladino. Mom has always said that this was their family’s native language, and it’s a bit like Spanish, but I didn’t really understand what they were saying, because I never understand everything in Ladino; my parents have always wanted us to speak French at home, so that we fit in better at school and everything. I had no idea why they were reacting like that, because our teacher had impressed on us what a good thing the armistice was. It made me think of what happened last week, when almost everyone in Paris was trying to get away. It was only then that it clicked: it’s the Germans that everyone is so afraid of!

Thursday October 3, 1940

Dear Diary,

Today was the first day back to school after the summer vacation and everything felt so different. Mom woke us up early this morning. I put on my best dress, the blue flowery one, and brushed my hair to perfection so as to “make a good impression”, as Dad keeps telling me I should. Then I set off to school with Maurice, Mathilde, Jacques and Mom, taking the route I know so well. I was excited because I was going to see my friends again, girls I hadn’t seen for so long, but also nervous because everything will be different this year. Still, I hope that school will always feel like a safe, homely place…

It’s only a few minutes’ walk, so we soon said goodbye to each other in front of the school. Mathilde and I headed off to the right to meet up with our girlfriends, while Jacques went left towards the kindergarten. Maurice goes the elementary school for boys on rue Vitruve, which is in a different direction.

Classes started normally enough; we had French, math and history lessons as usual, but I had a hard time concentrating. My thoughts were elsewhere, as if I were still on vacation!

I love getting home in the evenings at back-to-school time, when everyone sits round the table talking about how their day went, what their new teacher is like, who’s still in their class and such, but mealtime tonight was strangely quiet. I overheard Mom and Dad talking in the kitchen about some new laws about to be passed in France to restrict our rights. I didn’t understand all of it, but they seemed really worried. I went bed soon after that though, because it had been a tiring day.

Tuesday October 8, 1940

Dear Diary,

Dad left home early this morning. He had that serious look on his face that he always has when he has something important to do. Mom said he was going to the local police station to register us all in a census. I didn’t really understand what that meant, but I could feel the tension in the air. Mathilde tried to keep me occupied playing with dolls, but I could see that she was worried too.

Census card, 1940

Source: ©Shoah Memorial/ French National archives, file on PINTO Menahem ©French National archives in Pierrefitte, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5657_066342_L.

The 1941 census sheet. The name of the last Pinto child has been covered up at the request of the French National Archives service.

Source: ©Shoah Memorial/ French National archives, file on PINTO Menahem ©French National archives in Pierrefitte, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5622_020683_L

Thursday October 10, 1940

Dear Diary,

Dad got home very late last night. He didn’t say a lot, but he did say that we all have to be very careful and stick to the rules. We all asked him loads of questions, even Albert and little Jacques, but he wouldn’t go into much detail. He just said it was for our own safety. I don’t understand what’s going on. All I know is that the world around us is changing, and these changes are not good news for us Jews. Mom spent the whole evening praying.

Saturday October 12, 1940

Dear Diary,

According to what I heard on the radio today, things are getting worse and worse for Jews all over Europe. They were talking about new laws that will apply to us, but I didn’t quite understand it all. What I do know is that Mom and Dad are very sad and upset about it. Maurice is too young to understand what’s going on. I wish I wasn’t old enough to understand.

Thursday October 17, 1940

Dear Diary,

Mom spent the day hiding some of our most treasured belongings. She says it’s “just in case”, but I can tell she’s worried. She hid some photos and letters. Dad says we all need to know where to find our important paperwork. It’s odd, it feels like we’re playing some kind of a game, but I know it’s far from a game.

Saturday October 19, 1940

Dear Diary,

This evening, at dinner, Dad said he’d heard some rumors at the police station. It seems things are going to get even tougher for Jews here. He said we should be prepared at any moment for… he didn’t finish his sentence. I wonder what we have to be prepared for. I’m scared, but I know I have to stay strong for Maurice, who doesn’t understand what’s going on. Mom and Dad are doing their best to keep us safe, and we’re all trying to pretend everything’s normal. But it’s really not.

Monday October 28, 1940

Dear Diary,

Something terrible happened today. The radio was on in the dining room. Mom told me to go to my room before I had a chance to hear what they were saying, and then told me not to listen.

But how could I not listen when the adults’ voices sounded so anxious? When I got to my room, I pressed my ear to the door, trying to hear what they were saying. I couldn’t believe my ears. Hitler had come to France to meet Pétain, and they had shaken hands, and then Pétain announced something that sent shivers right through the house. He said that the French government was going to “collaborate” with Hitler. I could hear my parents crying in the room beside mine. I didn’t know exactly what “collaborate” meant, but I knew it must be bad news for us all. On my way to school tomorrow, I’m going to buy a newspaper…

The front page of Le Matin newspaper reports the meeting between Pétain and Hitler at Montoire on October 24, 1940. Source: retronews.fr

Wednesday November 6, 1940

Dear Diary,

Mom went to the market today, as she always does on Wednesdays. She shops three times a week because my siblings and I eat so much. But today, when she got back, instead of the hot rolls she usually brings us, she only had a little bag containing some rice, pasta and a small stick of bread. She looked worried and went to see my father in the kitchen. I’m curious, Dear Diary, and that’s not good, because curiosity killed the cat, but I couldn’t help overhearing their conversation. My mother was talking about “ration coupons”, which was the first time in my life I’d heard that expression, but it was what she said next that filled me with dread. She told my father that if they can’t find a way around this, we’re all going to starve to death.

A sheet of ration coupons, Paris departmental archives. Source: archives.paris.fr

Thursday January 2, 1941

Dear Diary,

My darling little sister, Mathilde, turned ten today! Wish her Happy Birthday!

Thursday April 10, 1941

Dear Diary,

Something important happened today. I saw lots of grown-ups standing talking on the streets, looking worried. Then, as I went by the newsstand, I saw a big billboard with the front page of “Le Matin”: “Salonika has fallen, taken by the German army”. Mom asked me to buy the paper for her. She can’t read French very well, so I promised to read it to her when I got home.

When I got home, I starting wondered what this all means. Why is it such a big deal? Why is everyone so worried? More importantly, what does being Jewish have to do it? Mom and Dad don’t talk much about these things. They keep saying that we have to be careful, but they never tell us why.

There are children from all over the place at our school, from different cultures and religions. Some are Catholic, others are Protestant, and there are even a few Muslims. So I wonder why being Jewish is so different. Is it just another word to describe us? Or is there something deeper, something more important?

Next, I read the paper to Mom. I thought maybe she could explain a bit more about what this all means for us Jews. I came home with the newspaper under my arm, as I promised. She was sitting at the kitchen table sewing, but as soon as she saw the paper, she had a curious, concerned look in her eyes . I sat down beside her and began to read the headlines out loud.

“Salonika has fallen, taken by the German army”, I began. Mom stopped sewing and listened intently. She nodded from time to time, but I could see in her eyes how worried she was. When I was done, she took a deep breath and gently laid her hand on mine.

“Thank you, darling,” she said softly. “It’s important to keep up to date with what’s going on in the world.” But I could hear something more in her voice, a kind of sadness tinged with resignation.

I asked her what this meant for us Jews, and if it was anything to be afraid of. Mom looked at me fondly, but with a hint of sadness in her eyes. “We have to be careful, darling,” she said softly. “But we mustn’t live in fear either. We have to carry on living our lives, loving our family, and worshiping as usual. These are the things that give us strength.”

I hugged her, comforted by her warmth and energy. Mom is an extraordinary woman, so wise and courageous. I know I can count on her to guide me through the difficult times ahead.

Le Matin newspaper reports that Salonika has fallen into the hands of the Germans. Source: retronews.fr

Tuesday July 8, 1941

Dear Diary,

Dad broke some awful news this evening: his business has been “Aryanized”. He often talks to us about his work: he’s a lingerie seller. Up to now, he bought his products from wholesalers (people who sell a lot of goods at a time for their customers to sell on). There are several lingerie wholesalers in the 11th district, mainly based around rue Sedaine, which is why Dad went into business there. He had a very small business, so small that it seems weird to call it a business at all, because he was the only one working in it. He’d go to the wholesaler and wrap up all the lingerie he’d bought in a large sheet, which he’d tie into a bundle. Then when he got to the markets, all he had to do was untie it, and he could sell the panties, bras, socks, etc. to passers-by. He called himself a “bundle vendor”.

I know, you’re wondering what Aryanization is, right? Dad explained it to me, but I still don’t quite get it. He told me that his business had been stolen from him because of our religion, because we’re Jews. It has been handed over to an “Aryan”. What are “Aryans”? They’re supposedly “perfect” people: blond-haired and blue-eyed – nothing like Jews at all!

His business was confiscated by a man by the name of Mr. Legrand [the big/tall in French]. A big man stealing from the small one… ironic, isn’t it? This thief gets paid 500 francs for doing it, can you believe it? He destroys us and makes money out of it at the same time. We didn’t have much money to begin with, but what’s going to happen to us now? Dad’s really miserable; he can’t stop crying. Mom is trying to pretend that everything’s fine, but I can see that she’s worried too. She can hardly sleep at all these days and you can see it in her face. Dad doesn’t sleep much either.

Yesterday, he had to go and hand in his “medal”, which was proof that he was trading legally. He was embarrassed, and deeply ashamed. He went out with his head bowed and didn’t come back until two hours later, with his eyes all red from crying. Mom made potato soup to make him feel better. He didn’t even touch it.

I didn’t eat any soup either. What can you do? You have to let the little ones have it. I’m the eldest, I have to take some responsibility too…

Dad came over to me after dinner and gave me a hug. Both of our stomachs were rumbling. Then I read to him from the one and only book we own, Les Misérables. I almost know it by heart. We had to sell all our other books, but Dad insisted on keeping this one. Every time I read it to him, it reminds us that we’re not so unhappy after all. At least we have a family and a roof over our heads… and most importantly, we love each other.

Wednesday August 26, 1941

Dear Diary,

This tragedy was bound to happen. I can’t even begin to tell you how sad I am because my tears are stopping my thought process. I still can’t quite believe it!

My dearest Dad was arrested today. I have to tell someone, but I’m Jewish, so it’s better that I don’t tell my friends, and Mom is too devastated to talk about it. I just knew it would happen one day; I could feel it. I warned Dad over and over again how dangerous things are, but to no avail. I remember clearly that I had a bad feeling this morning and asked him not to go to work. I told him yet again that there was no point in overdoing it and that staying safe was more important. But we’re talking about my father here, who never shies away from anything and isn’t afraid of anyone. He’s not just anyone, my father, he feels responsible for supporting the family and works hard so that we can have enough to eat. He’s even willing to trade on the black market to provide for us. He went out with his little bundle of stuff to barter and never came back. It was only later that my mother, my brothers and sisters and I heard that there had been a roundup all over the neighborhood.

After it happened, it was all anyone could talk about. It seems that the military police, firefighters, local guards and military personnel were all brought in to help.

According to the woman who runs the café across the street, more than 3,500 Jews were rounded up if they were unlucky enough to be away from home. They were all taken away in rented trucks and buses, but no one knows where to. She told us, sadly, that she had seen some policemen grab my father by force and put him on a bus. Mom was devastated. When we got home, we all cried. Oh, poor Dad! How are we going to get you out of this? And what will happen to us if we stay here? We’ll be next, and Mom knows it. She’s not only worried about my father but also about us, his children, because she knows as well as I do that the Nazis have no mercy and won’t hesitate to arrest Jewish children as well. I’m frightened. But we have to deal with it, we have no choice.

This day will be forever engraved in our memories. It was not only the day on which my father was arrested, but also a day that will shape the future of our entire family.

Thursday November 6, 1941

Dear Diary,

It must have been around midnight last night, and as happens every night, I couldn’t get to sleep for thinking about Dad. I heard the door open, then the sound of footsteps and a piercing shriek. In an instant, I decided that it was the Germans coming to take us away, and I just froze and lay silently in bed.

I waited a few minutes and heard nothing but whispers, so I wondered who on earth it could be.

After a while, I got out of bed, went into the living room and saw a man sitting on the sofa. He was horribly thin, filthy, looked like he was in pain and had a blank, dark stare in his eyes. The more I looked at him, the more familiar he seemed, and then suddenly it hit me: it was Dad!

I rushed over to give him a hug, but he didn’t say a word. He just gazed at me affectionately, and when my brother and sisters came in, you could see the joy in his eyes; at least that’s what I think it was. He had a blank expression on his face, and yet you could still just about tell what he was thinking.

He still wouldn’t speak, and for a while I was in despair, thinking he might never speak again. But a bit later, he told me how happy he was to see me again, and how many times he’d dreamed of this moment! With those few words, I recognized him as my father again, and I was so relieved that I hadn’t lost him after his stay (if you can call it that) in Drancy. I hope I never go there!

Monday November 17, 1941

Dear Diary,

It’s been two weeks now since Dad came home, but it was only today that he started to tell us about what he went through. We asked him what life was like there, in Drancy. Mom didn’t want him to tell us the details, but he said we ought to know, because sadly, it was the truth.

He was taken to Drancy, a word that now conjures up visions of hell in our house. He looks so tired, so different. He’s had nightmares every night since he came home. Sometimes his screams wake me up. It’s terrifying.

This evening, after dinner, when Maurice, Albert and Jacques were already asleep, Dad called Mathilde and me over. He wanted to talk to us. His voice is still weak, but he did his best to explain things in a way we could understand, without frightening us even more.

Tuesday November 18, 1941

Dad continued to tell us his story today. He told us some more about Drancy camp, where he was detained. He said he tried to stay strong and hopeful, but every day was a challenge. He described the camp itself. It was a “horseshoe” shaped building, so it was easy to fence it off with barbed wire and easy to watch over it. He said there were five floors, and that it was built around a courtyard that looked to be around 200 yards long and maybe 40 yards wide. The internal walls on each floor were not finished, as the building work had not been completed when they started imprisoning the Jews. It was made up of large rooms and the inmates had to sleep on the floor. Dad told us that every night was even more awful than the one before. There were between 50 and 60 men in each room: he was in block H, on staircase 15 and in room 12. They had no straw mattresses to sleep on and no blankets. He said that the camp was beside five huge tower blocks, in a housing estate called the “Cité de la Muette”. He said there was no running water or lavatories, and the smell was unbearable. Oh Dad, my poor Dad! And he had hardly anything to eat! Food was hard to come by in the camp. Dad lived on watery soup, which was served in the rooms, with two measly sugar lumps. And this was my Dad, who loves his food! I’ve no idea how he managed to survive in such appalling conditions, but my father is no ordinary man, and he kept on fighting right to the bitter end! But that wasn’t all, because besides the lack of food, of course there had to be horrible diseases as well, otherwise it wouldn’t have been much fun at all. My father watched as people died all around him, one by one. Then there was an influenza epidemic, and as you can imagine, dear Diary, when everyone is crammed together in one room, flu spreads like wildfire. A lot of his fellow inmates died. Dad doesn’t know exactly how many, but the epidemic swept through the entire camp, and he reckons that the death toll was well over 3000. But then, on November 5, he was suddenly released! The Germans decided to let nearly a thousand internees go. I wonder if they felt sorry for these prisoners, although it doesn’t sound like they took pity on anyone. Dad told me that due to the lack of sanitary facilities and the hunger, the men didn’t even look like themselves, and he was right, that was exactly what we first noticed when he came home.

He also talked about the guards, and how they treated people so unkindly and with so little compassion. Dad said there was very little food and the water from the faucets was cold. But he also mentioned instances of solidarity, of strangers becoming friends, sharing whatever they had, supporting each other in their darkest moments.

Even though what he described was truly horrendous, I suspect he left out a few important “details”. He told Mom more than he told us, but I think we all deserve to know.

Wednesday November 19, 1941

Dear Diary,

Today, Dad told us about the day he was released; he couldn’t believe he was finally going home. The Germans let him go because they had made him sick by not feeding him enough and treating him like dirt. But he also said that even now, as a free man, he doesn’t feel truly free. Memories of Drancy still haunt him, and he knows he’ll be in poor health for some time to come.

Dad tried to reassure us that everything will be fine now that he’s back home with us. But I only have to look at him. He’s right here, but at the same time, he’s miles away, lost in thought and haunted by traumatic memories.

He says we have to stick together, and love and support each other, no matter what. He says our family is all we have, and what makes us strong. Mathilde, Albert and Jacques all had tears in their eyes. We all promised to stand by each other.

Dad finished by saying that despite everything that has happened to him, he’s still optimistic. He hopes for a better future for us all. I want to believe in that hope too. But when I close my eyes, I hear Dad having nightmares, and I wonder if a better future is even possible after all he’s been through.

Sunday December 7, 1941

Dear Diary,

Today we played in the building with Albert and Marie-Louise Bandkleider, our neighbors (their eldest is called Albert, like our Albert, who’s the same age as Marie-Louise). It was great fun, especially playing hide-and-seek. With five courtyards and stairwells, there are loads of potential hiding places, which makes the game more challenging for the person searching but easier for the ones who are hiding. It makes it more fun. I was the seeker twice, and the rest of the time it was Mathilde or one of the Bandkleiders. Albert Bandkleider is the same age as our Maurice but he’s more quick-witted. Maurice didn’t want to be the seeker actually; he didn’t feel up to it. I can see why, he’s sick, but still, it’s part of the game. But anyway, it didn’t matter, because the other kids were there.

We also played at being cats in the courtyards, where we could move from one to another easily. Only then we made a bit too much noise, and one of the neighbors told us off, but it was no big deal. The main thing is that our parents don’t find out, because then we won’t be allowed to play together anymore. They’re afraid of everything these days….

I can’t wait to play with them again – we had such a great time!

Plan of the building at 48 rue des Haies. Source: Paris departmental archives, ref. 3184W 2461

Friday May 22, 1942

Dear Diary,

It’s been ages since I’ve written anything!

Dad spoke to us this evening about “black markets” and “illegal bartering”. Now I realize that his way of getting food for us is to trade it for other things, and that’s against the law. It seems to me that if even my father is willing to commit a crime, then things must be really bad. When they’d finished talking, I went to see Mom and asked her to explain the problem. She told me all about ration cards, a sort of identity card for food, and then the cardholder gets coupons (for monthly rations such as sugar or coffee) and tickets (for weekly or daily rations), which have to be handed in to shopkeepers when paying for the goods.

Yesterday I found a little notice on the ground on my way home from school. It makes more sense to me today… but does it apply to Jews too?

Definition of consumer categories for assigning ration cards, Seine prefecture supplies department, May 1942. Source: © French National archives, ref. PEROTIN/609/52/1/1 1. Source : Archives.paris.fr

The problem is that these rations alone are not nearly sufficient; we simply don’t have enough food. I looked at my ration card today and I see there’s a letter and a number “J2”. I guess it’s a children’s card. I’m scared. Will we manage to get enough to eat until the war is over? What if the war never ends? I’m scared, Dear Diary, and I don’t know if there’s anything I can do to help my family. First rationing, and then what? I’m scared, no, terrified about it all in fact.

Monday June 8, 1942

Dear Diary,

Today, when I went out, I had this yellow star sewn onto my coat. People kept starting at me, more than I thought possible, even just on the street. Passers-by crossed to the opposite sidewalk and children stared at me. Some people even pointed at me. I thought I must have something on my face, but no, it was all to do with this star. My God, it was hard…

Even at school things are different for me now. Some girls don’t even talk to me anymore. Luckily, my friends behave the same way towards me. We’ll see what happens to Maurice, maybe the boys will be different, I just hope they won’t make fun of him. But in any case, he’s staying at home for the time being because he’s sick. He’s been having his attacks again; I do hope he’ll get better soon.

I had no idea that someone’s religion could change so many people’s attitudes. It’s not as if I’m some kind of freak, is it? So why are people looking at me like this? And how are we going to go out to play?

Even at the bakery, everything was different! It felt like the woman gave me the stalest bread she could find. I’ve also heard that there are going to be bans on Jews. The worst thing is that last night, when I sewed my star on my coat, I thought it was pretty, and that it added a little touch of color. Oh, how naive I was!

Thursday June 11, 1942

Dear Diary

Mom was feeling really tired today, so she suggested that Maurice and I go to the movies. I was thrilled, because we rarely get to go out these days. We went in the afternoon, hoping to catch a good movie. The movie theater is called the Saint-Ambroise cinema . It’s quite a long way from where we live, at 82 boulevard Voltaire, but we went on foot to make the most of the outing. When we got there, we lined up as usual, and although the men working there were very nice, the moment they saw the yellow stars sewn onto our coats, they refused to sell us our tickets. Then they asked us to leave, and said the cinema “is not for you”. I understood immediately that “you” meant “Jews”. I didn’t really understand what was going on, and neither did Maurice, but I told him not to worry, it was no big deal and they’d soon get over it. But then I remembered a conversation I’d overheard between Mom and Dad. They were saying that they thought the government was going to start banning us Jews from a whole lot of things, so I guess going to the movies is one of them. So anyway, when we got home and I told our parents about what happened, they confirmed what I’d been thinking. They said that while we out at the cinema, the neighbors had told them about the new restrictions. Jews are no longer allowed to go to the movies, go to public parks and gardens, use the subway or even use telephones. It took a minute for this to sink in, but when I realized how awful it is, I started crying. It was bad enough having to put up with people staring at us on the streets, but now we can’t even go to the movies! I’m going to miss that so much… I really want to rip off this yellow star I’m stuck with, as if there’s something wrong with me. A star does not define who I am.

Monday June 15, 1942

Dear Diary,

Today I took the subway for the first time wearing my yellow star. Mom told me to stay close to her and ignore anyone who stared at me. She explained that it was now compulsory to wear the star, but that we mustn’t let it stop us from getting on with our lives.

When we walked into the station, I could feel the eyes on me immediately. People were avoiding us and moving around the car so as not to get too close. One old lady gave me a sad look, then promptly looked away. Mom squeezed my hand tighter, and I tried to concentrate on her face.

Those few minutes on the subway seemed like an eternity. I just wanted it all to be over, and to get out of there and go home. When we eventually got off, I breathed a sigh of relief, but there was still a part of me that was sad and angry. Why do they have to treat us like this? How come this star makes us feel like strangers in our own city?

Monday July 13, 1942

Dear Diary,

The grown-ups are all talking in hushed tones these days. They’re sharing news and passing on rumors about what’s happening elsewhere in Europe. I’ve heard that whole families like ours are being taken away. I wonder what we should do. Mathilde tries to tell me everything will be fine, but there are times when I see her crying in secret. It makes me really nervous.

Friday July 17, 1942

Dear Diary,

We had a real fright yesterday. The police came into our building, and there was a lot of shouting, banging on doors and people going up and down the stairs. Mom and Dad told us to keep quiet, and not say a word. We all huddled together and didn’t open the door.

This morning the concierge told us that they had arrested our friends the Bandkleiders, their whole family, and that the police had put them on a bus. A policeman told her that they were taking the Jews to the Vel d’Hiv, the winter cycling track. I can’t help wondering what’s going to become of us… I’m so scared tonight.

Friday October 2, 1942

Dear Diary,

We’re back to school today. When Mom woke us up this morning, she seemed anxious. I expect she’s worried about poor Maurice. He’s only just moving up to second grade because he had to do his first year again, so he’ll be the tallest kid in his class. I hope his fits won’t mean he can’t go to school again this year. Some students didn’t come back to school this year. I think they may have been rounded up, like Albert and Marie-Louise, our neighbors. Rumor has it they were taken to Drancy, where Dad was interned last year.

December 5, 1942

Dear Diary,

Dad went to school today to tell the principal that Maurice is sick again. He was really worried because this isn’t the first time Maurice has been ill this year. I think what Dad is most afraid of is that his son will have to repeat the year again! He’s already done first grade twice and now he’s in second grade. I hope he gets better soon so he doesn’t have to repeat this year as well!

Wednesday January 15, 1943

Today I asked Mom to tell me the story of the great fire in Salonika, where she was raised.

She told me that when she was 14, a huge fire devastated the city, even though she and her family prayed every year on Yom Kippur. She said that all the Jews in Salonika prayed that this disaster would never happen. They knew the city was at risk because almost all of the buildings were made of wood. But sadly, prayer wasn’t enough. Mom had tears in her eyes when she talked about it, and I can see why: she finds it really tough to think back to that time, and I know that her neighbors (including a girl her own age with whom she was very close) didn’t manage to get out in time. She also admitted that she was terrified at the time, and that she still has nightmares about it (I think she’s afraid of it happening again, and that the mere idea of losing people she loves again gets her into a state that I can’t even imagine). At the end, she showed me some photos and a newspaper article about what happened:

L’Echo de France, the French newspaper in Salonika, describes what happened on August 19-22, 1917. Source : Wikipedia

Monday January 25, 1943

Dear Diary,

Mom often tells me a bedtime story. Last night, she shared a childhood memory with me, from when she was still living in Turkey: it was a beautiful spring day, and she was walking with her father to the tobacconist on the Place de la Liberté.

Everyone was walking fast, and there were queues outside all the stores, especially at the tobacconist’s, where well-dressed men were chatting about all sorts of things Mom wasn’t old enough to understand. She was mainly interested in all the women who were passing by. Some of them were just strolling along the streets, enjoying the exhilaration of city life, while others were striding purposefully down the main street. She remembered two women who looked happy to be together, judging by the smiles on their faces, but what struck Mom was their totally contrasting outfits. One was dressed in fashionable European clothes, the other in traditional costume. Mom then lost sight of them as she made her way towards the main street, where the “Sabri Pacha” newspaper banner hung, and to the right of it was a portrait of Namik Kemal, a famous poet and journalist.

Photo by Ali Eniss, Place de la Liberté in Salonika, around 1908-1909. Source: Salonica, Jerusalem of the Balkans exhibition at Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, in Paris

As I pulled open the chest of drawers today, I found a dusty box full of old postcards and newspaper clippings, things that remind Mom of Salonika. There’s even a picture of the tobacco shop from her story, I think. I find it funny that this was in what is now Greece, but all the store signs were in French!

Postcard of Salonika, late 19th century. Source: Salonica, Jerusalem of the Balkans exhibition at Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, in Paris

Dad tells me that Salonika looks a lot like Constantinople, where he grew up, and I should look in the school library to see if there’s a book about it. He rummaged through the pictures in the box and fished out this one: it’s a picture of a bakery taken very close to where he used to live.

A Jewish baker in Constantinople, by Frank G. (Frank George) Carpenter, 1855-1924. Source : Wikipedia

The baker is standing in front of his window display with lots of big loaves of bread. There’s writing in all the languages spoken in the city, in Turkish and Greek, English and Armenian, and of course in Ladino (those are the Hebrew characters), and this was in Dad’s neighborhood.

Friday February 5, 1943

Dear Diary,

In the very same box, I found some photos, my mother’s souvenirs. One of them is a picture of a woman. I went to find Mom to tell her what I had found. I asked her who this person was and she told me it was a woman who looked a lot like her mother, my grandmother. She also told me about all the various types of clothes women wore where she used to live.

Pascal Sebbah, studio portrait of a Jewish woman, around 1875. Source: Salonica, Jerusalem of the Balkans exhibition at Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, in Paris

The women mainly wore baggy pants, with dresses called “entari”, open at the front, with arm-length slit sleeves and a belt. Sometimes, women wore coats with fur trim over their outfits, and a headdress with a chinstrap. On feast days and holidays, my grandmother also wore a lace or embroidered top. I though all these fabrics were really pretty, but Mom told me that she had left this traditional dress behind in Salonika, because she had to adapt to Western styles so she would fit in better. I thought this was a real shame, because I’m sure it would have suited me perfectly.

Saturday February 6, 1943

Dear Diary,

This morning, following our chat yesterday, I asked Mom if her father and the other men who lived in her country dressed in the same way as Dad and Maurice. She told me to sit on the sofa while she went to fetch something. When she came back, she had another box full of photos in her hand. She gave me some of the ones below. She explained that men (and women) there always covered their heads with either a turban or a fez, like the men in the center of the second photo.

Jewish workers in Salonika, studio photo, late 19th century

Above right, photo by Ali Eniss, Children on a walk along the ramparts.

The photos on the left and right are from the Salonika, Jerusalem of the Balkans exhibition at Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, in Paris, and the photo in the middle is from commons.wikimedia.org

Monday March 1, 1943

Hello Diary!

I’m so happy today! I worked hard in class and joined in when the teacher asked us questions. When I got out of school, I was surprised to see my mother waiting for me right outside! Mom never usually comes to walk me home from school, but I think she’s afraid something will happen to me now, with all this discrimination against Jews. I ran up to her and gave her a big hug, I was so pleased that she came to pick me up!

My teacher must have seen us hugging from afar and came over to us. First of all, she congratulated me on my progress and told my mother that I was a very good student, smart and sensible. She went on to say how proud she was of me and my efforts in class. It was the first time that my teacher had ever congratulated me on my work but she also said that I should join in more, as I had done today.

My mother looked at me and a flush of pride swept over her face. She had only picked up on the positive aspects of what the teacher said. Phew!

On the way home my mother gave me a packet of sweets, which is something she never usually does. I guess I’d put a smile back on her face, despite recent events. I thanked my mistress silently for her praise, even though I suspect she only came over to see us because she felt sorry for us with our yellow stars.

Thursday April 15, 1943

A little girl outside a factory in Salonika. Source: Salonika, Jerusalem of the Balkans exhibition at Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, in Paris

Dear Diary,

While Mom and I were tidying up, we found this photo. She’s not sure, but I think it must be her, because in her day, little girls used to work in Salonika. Mom’s family wasn’t very well-off, so I think she worked in the factory behind her in the photo. She couldn’t read or write when she arrived in France; she wasn’t as lucky as I am. Even though school is a little boring sometimes, she wouldn’t have been able to write a diary like I do. And I’m appalled that such young girls had to go out to work.

Friday April 16, 1943

Dear Diary,

My little brother Maurice turned ten today. I remember when he was born, even though I wasn’t even four at the time. I went with Dad and little Mathilde to the maternity ward at Tenon hospital to pick up Mom and the baby. Poor Maurice, ten years old and still so frail.

Saturday May 29, 1943

It’s my birthday, I’m fourteen! I’m all grown up now, but hey, it’s wartime, so no presents for me this year. Guess what, Dear Diary, I asked Mom why we never celebrate her birthday? First of all, she told me that we didn’t celebrate grown-ups’ birthdays and that people didn’t usually say how old they were (ha, she’s forty, she told me), and then she explained that she didn’t know exactly what date she was born, just the year: 1903. Poor Mom, she must have had a tough childhood!

Wednesday June 30, 1943

Dear Diary,

I received my 3rd trimester report card today and I’m going to do business studies next year.

The teacher’s comments on Esther at the end of the 1942-1943 school year. Source: Paris departmental archives, school records, ref. 2885W 1

I’ve also looked at the grades on my report card, and they’re not great. My teacher said my work was “half-hearted”. To be honest, I’ve made more of an effort this year! My teacher isn’t very nice to us anyway, or at least she doesn’t give very positive assessments! She wasn’t very kind to my friends either, she said some of them were of “mediocre intelligence” and even told some of them that their “appearance is mediocre”!

Anyway, never mind, Mom is very happy with me and the fact that I’m taking a business course, and the teacher even said that I was intelligent (it’s in my report)!

Monday August 23, 1943

We’ve been living on bread and water for three days now. Our bellies are constantly rumbling with hunger. Dad has been depressed ever since his business was Aryanized; I can hear him crying in the bedroom. Mom occasionally goes to the bakery to beg for bread. What she comes back with is pitiful. What a sorry state we’re all in.

I daydream to pass the time. If I didn’t, the gloomy atmosphere would be even more unbearable. I dream of people who live melancholy lives like ours. I picture myself as Gavroche, even though my family members don’t represent the characters in Les Miserables.

Yesterday, I heard Mom tell Dad that we had no choice but to ask the “UGIF ”* for help again. It’s not the first time, and I think she’s already made quite a few requests. She has applied for board and lodging for Maurice, and for me too, so that I can take care of him.

*I believe UGIF stands for Union Générale des Israélites de France (General Union of French Jews). Dad told me that this is an organization that helps Jews, because the people there know how bad things are for us.

Tuesday August 24, 1943

Dear Diary,

I don’t remember what day this happened, I’ve only got around to writing it down today… but Maurice and I have been placed in a UGIF children’s home. Mom’s application was successful: we were offered places in this new facility.

We’re now boarders here at the Lucien de Hirsch school on avenue Secrétan, but I don’t know if we’ll be going to school here too, or if we’ll carry on going to our usual school – well, the usual school in Maurice’s case, but not mine. I’m supposed to be starting a new school on October 1st – on rue de Ménilmontant. Will I still be able to go, I wonder?

Yes, it seems that I am indeed going to go there!

The Lucien de Hirsch school, date unknown (first half of the 20th century). Source: Lucien de Hirsch school archives

Friday October 1, 1943

Dear Diary,

It’s back to school time for me, the start of my first year at the business school in Ménilmontant, but will I make it through to the end? So many people are being arrested and vanishing…

Sunday October 17, 1943

Dear Diary,

Last week, I had to go to a little room to be seen by a nurse, a doctor and a dentist. They all said I was fine, but that I needed to eat more. I told them that there wasn’t enough money for that.

There are some children with us who came here from another shelter (the Lamarck center, I think it was) but now they’re staying with us. Yesterday, one of them fell and hurt his knee. The manager of the previous center asked for him to be taken to hospital. He had an “X-ray” taken and it turned out to be nothing more than a contusion (a sort of bruise in his knee, I think).

As for the food, there’s no shortage of fruit and green vegetables in the school dining room, but we have very little pasta or pulses. During the first few weeks, we used to have a small glass of beer, but on stormy days, it turned sour. We’re usually given green vegetables and some pasta in soup, or dried peas and beans. Sometimes we have jam or stewed fruit for dessert. We’re thrilled when that happens!

There’s talk of them setting up a 6th grade class, starting on October 18. Children who have passed the French DEPP will be allowed to go to it, and the others will study for the CEP, which you can’t take until you’re 14. I’ll be that age in MayI’ve heard they intended to hold Latin and English classes, but they don’t have an English teacher. Miss Françoise Meyer is apparently willing to teach Latin, and another teacher at the school has agreed to cover the rest of the subjects. I’d absolutely love to take those classes…

The school kitchen, date uknown (first half of the 20th century). Source: Lucien de Hirsch school archives

We’re all shocked and saddened by something that’s been happening at school lately: one of the kitchen staff, Ms. Semo, who is usually very kind and friendly, is behaving really strangely at the moment. One minute she seems to be in a totally normal frame of mind but if anyone makes the slightest remark, even if they’re right, she suddenly flies off the handle. People say it’s hysteria, or dementia. The other day, while she was washing spinach, Mrs. Blotch mentioned that there were some perfectly good leaves lying unused on the floor. The cook flew into a rage, tearing at her hair and letting out terrifying shrieks. Apparently, similar incidents have happened before. It’s hardly a pleasant sight, either for us, the residents, or for the poor woman’s family and friends.

Another thing that has happened lately is that some students have been complaining about thefts of small sums of money. Someone said that one of the students, I don’t know who, had been seen picking up a bundle of 5-franc bills. The principal launched an investigation. I believe he called the boy’s parents in and threatened to expel him if it happened again.

Monday October 18, 1943

Dear Diary,

Yesterday, one of the children from Lamarck noticed that 65 francs had disappeared from his wallet. It seems that the theft took place while he was playing in the schoolyard with some of his classmates. The principal called us all into the covered play area, and searched everyone thoroughly. Maurice was very impressed. Nothing was found, but a few minutes later, the UGIF plumber found the money in the toilets, where he was doing some repairs. I don’t like this atmosphere, not one bit.

Friday January 11, 1944

Dear Diary,

The UGIF organizes lots of activities for us: on Tuesdays and Thursdays, the supervisors lead “guided activities”. They split us up into different groups: some read for an hour or two in the library, others play sports in the gym, and others amuse themselves in the schoolyard when the weather’s fine, or in the covered play area if it’s raining. At four o’clock, we all have a snack, which includes a sweet drink and “protein cookies”.

Students in the schoolyard, date unknown (first half of the 20th century).

Source: Lucien de Hirsch school archives

The school building and the courtyard, photo taken on May 15, 2024

Today, for the first time, we went to the Lamblardie stadium. We all came back quite delighted but also very tired. We were very hungry at dinner, and cheered when each dish was served and we heard shouts of “Mmm, that’s good!” from all around the room. But it must be said, unfortunately, that we still don’t have enough pasta or pulses.

In other news: Ms Gaignon, the cook, is sick. Also, the managers are delighted because about half a ton of coal was delivered today, just as we were starting to run out. Well good, because it’s been really cold these last few days!

Friday 4 February, 1944

Dear Diary,

Today, we played sports! When it came to selecting the teams, the school excluded (temporarily) the youngest children, because they might not have been able to cope with four subway journeys. So there were about 75 of us, and we were divided into two mixed teams of roughly the same size: Team A, which I was in, and Team B, which Maurice was in. Those of us in Team A were aged between 11 and 14, all students from the CEP class and 6th grade. We had to be at the stadium for around 9 a.m. and leave again at 11 a.m. in order to be back in school by lunchtime, which is around 11.45 a.m.

Team B was made up of 40 students aged between 9 and 11, all from the DEPP and elementary school classes. They went to the stadium at 2 p.m. and left at about 4 p.m.

Speaking of sports, we’ve been told that each of us will be given a sports record sheet detailing our name, age, weight, achievements and whether we are not allowed to do any particular activities. Maurice will probably be excluded from most activities due to his seizures. I suppose he’ll end up watching the others most of the time.

I always look forward to the weekend, because on Fridays, now we do more sport, we get larger portions of food than usual: we have some pulses, beet and potato salad, thick soup, something with fish or eggs, and a dessert of sweet soft cheese or jam! We take our daily ration of vitamin-rich cakes and 2 lumps of sugar with us to the stadium! Our principal, Mr. Leibovici, comes to see us at the stadium once in a while, so then we have to be on our best behavior!

Saturday March 4, 1944

Dear Diary,

Here’s some news about what life is like for Maurice and me. They say there are an average of 80 students in the center during the daytime. We’re so lucky to have a team of medical, domestic and teaching staff.

Mr. Armand Kohn paid a visit to the school during the week when there was no heating because we had run out of coal, and everyone in the school was suffering from the cold. He then took action, and the heating is up and running again now. Also, one of our teachers told us that almost all the school’s requests for food supplies had been granted. We all get decent meals now, well, as far as that’s possible. A few of the Lamarck children have missed classes recently. I don’t know why exactly, but I heard they’re sick.

Monday May 15, 1944

Dear Diary,

It’s been ages since I’ve written anything… A few days ago, the nearest subway station was closed down. It’s called Buzenval. I wonder what’s behind it all… But in any case, we Jews aren’t really allowed to take the subway anymore, so it makes no difference to me.

Plan of the Paris metro (subway) in 1944, showing the stations that were closed. Source: archives.paris.fr

Monday May 29, 1944

Dear Diary,

I turned 15 today. My birthday feels odd this year, there’s absolutely nothing to celebrate…

Thursday June 15, 1944

Dear Diary,

We’ve had a tough few weeks, but I have to tell you, Dear Diary, that things are looking up here on avenue Secrétan: all the teachers are back, there are more staff in the dining hall, and the same goes for the sickbay. Of course, there are 86 children here now. We had no vitamin-rich cookies for a few weeks, but they’re back now. In the current circumstances, we can no longer go to the stadium, so we do our gymnastics here instead.

The alarms go off day and night and make us so tired; no one ever really gets much sleep! Luckily, the teachers try to give us less work, which is just as well, because I’ve run out of steam, I can’t remember a thing!

For some time now, the locks on the school lockers have been forced open. Various books and school supplies have been stolen. There was an investigation yesterday, during which two boys confessed and handed in some of the loot. Here’s a strange thing though: they weren’t the older boys in the school. The principal said that didn’t matter to him and that the culprits would be punished as they rightly deserved. I wonder what they were planning to do with the stuff they’d stolen – sell it maybe?

The school dining room in the early 20th century (around 1905?). Source: Lucien de Hirsch school archives

Wednesday June 30, 1944

Dear Diary,

Mathilde and Maurice got their school reports today. Mathilde has been accepted for the business studies course! Her teacher said she was an average student, but she had a good personality, so that’s good! She seems happy enough with her report.

Mathilde Pinto’s June 1944 school report, from the student register. Source: Paris departmental archives, school archives, ref. 2885W 1

She’ll be going to school with me next year, on rue de Ménilmontant.

Maurice will be going into 3rd grade, at long last! I was beginning to think he’d never make it, given the time it took him to get through 1st and 2nd grade. His teacher said in her assessment that he was rarely in class, but that was only because he has a medical condition. Anyway, the main thing is that he’ll be in 3rd grade next fall.

I’m delighted for them both!

This is not exactly a report card, just the teachers’ end of year assessment. For Esther and Mathilde, it was quite straightforward: they moved on to a business school. As for Maurice, he should have gone into 3rd grade but didn’t turn up at the start of the school year because he had been deported, although this was not mentioned in the report. Source: Paris departmental archives, school archives, ref 2889W 1).

Thursday July 1, 1944

Dear Diary,

Classes broke up for the summer vacation today. A lot of the students have left, but those of us cared for by the UGIF are still here. Many of the children are orphans with nowhere else to go, and Maurice and I are better off here than at home.

This photo, taken in the first half of the 20th century, shows that the schoolyard used to be divided in two, as were the buildings, with one side for girls and the other for boys. However, it’s not clear whether or not they remained separate when the UGIF took over the school. Source: Lucien de Hirsch school archives

To keep us occupied, we’ve been assigned a dozen or so supervisors who lead activities at school 3 afternoons a week. Our gymnastics teacher also comes once a week to maintain our “muscular flexibility”, as the principal puts it. I’ve also heard that the Hebrew teacher has organized a special course for the boys who will soon be celebrating their bar mitzvah, so maybe Maurice will be able to do that next year!

Friday July 7, 1944

Dear Diary,

Dad didn’t come home tonight, apparently, and I’m really worried. He left without a word to say where he was going, he was due back ages ago and no one knows where to look for him. What’s happened to him? This really isn’t like him at all…

Saturday July 8, 1944

We’ve been told that the German militia and French police arrested Dad in a café on rue Popincourt (possibly during an identity check). No other details. He’s probably in Drancy, but who knows… Mom says Maurice and I should stay in the Secrétan home, but are we really any safer?

Thursday July 20, 1944

It’s a hot summer night here in the dorm room, and I can’t get to sleep. I miss my parents, but then I remember that most of the children here don’t know where their parents are or even if they’re still alive. A least I have my brother here with me. And I know Mom’s at home with Mathilde and the little ones. But what about Dad, where is he?

These beds seem to be getting more and more uncomfortable.

Saturday July 22, 1944

The corridor leading to the dorm rooms on the third floor of the Lucien de Hirsch school.

The back staircase from the dormitory floor to the central section of the school building. The children who were rounded up may have gone down this way.

At around 2 a.m. this morning, the Gestapo burst in, dragged us out of bed and took us away before we even had time to get dressed. We were all in our nightdresses and pajamas. It was still dark outside. I looked for Maurice and as soon as he saw me, he ran over to me. We held hands so we could stay together. Then they loaded us onto buses.

We were all crammed together on the seats when something terrible happened: we saw a young boy running towards the bus and trying to get on. He lives in the building opposite the school, on avenue Secrétan; I don’t think he knew where we were going. He looked quite poor and, from what he was saying, it sounded as if he’d thought we were going on a trip to the countryside, and he just wanted to come with us. Poor kid, he thought we were going on a picnic!

The German soldier who loaded us onto the bus made a grab for him, undid the string holding up his shorts, which fell off, ripped off all his clothes and then threw him off the bus. I think the soldier wanted to check if he was Jewish by looking to see if he was circumcised, which he wasn’t. Then we drove off.

We’re now in Drancy camp. It’s like a prison: there are big gates and there are Germans watching us – I think they’re called the SS. Despite what Dad told when he came home from here, I’m still very surprised by this place – I didn’t expect it to be so terrifying. The buildings are dark and eerie. Maurice was really upset so I tried to calm him down, but I was scared too. I miss Mom and Dad and wonder how long it will be before I see them again.

From what I hear, six UGIF shelters in and around Paris were raided as well as ours: there are children here from the homes on rue Vauquelin, in Saint-Mandé and in Louveciennes, as well as us, I believe. Aside from us, the 80 or so children, there are also around twenty grown-ups from the Secrétan center.

I just found out that Maurice and I have been given numbers, as has everyone else here. Mine is 22441 and his is 22442. We’re huddled together in a dark room with a bunch of other kids; it’s a good thing they didn’t see you, Dear Diary, so I could hang on to you, which helps keep me occupied. We’re on staircase 6, in room 3, and it’s just as Dad described, only worse. There aren’t even any bathrooms, and we can hear screaming and crying all day long. I’m seriously worried, but also hopeful that Dad is here too, because he was arrested about two weeks ago. I miss my parents so much. I feel like bursting into tears, but I don’t want to alarm Maurice, who’s already on the verge of tears. I think I’ll hide you, Dear Diary, I’m so afraid someone will take you away from me.

Tuesday July 25, 1944

Dear Diary,

I haven’t been able to write every day because I didn’t dare take you out of your hiding place. But today I did, because guess what – we’re with Dad! For a week or so he was in room 4 on staircase 19, then transferred to room 4 on staircase 2, and then the three of us were finally all put in room 2 on staircase 4. I’m so happy to have him back at last, even though he’s in a dreadful state. Maurice never leaves his side. I feel a bit better with him here, but I’m still afraid of what’s going to become of us: every day, more and more people leave, but I don’t think they’re ever going home. I don’t dare ask Dad, but the question weighs heavily on my mind. Will we ever see Mom again? And what about Mathilde, and Jacques, and Albert? I miss them all, especially Mom, I miss her so much. Dad says not to worry and that everything will be fine, but this place is absolutely horrendous and I’m afraid the living conditions are just as bad as what he told us three years ago…

Wednesday July 26, 1944

Dear Diary,

I’m cold, I’m hot, I’m hungry and I’m so tired. We sleep on wooden bunks. I wonder how Dad stuck it out here for two whole weeks. I want to get all this filth off me but I can’t, my whole body itches, I’m sure I have bedbugs or lice. If only they’d let us out… Or at least let us receive a parcel, or a little note from Mom… Oh, how I miss my old life… Ah, I have to go now, they’re calling me and I don’t want anyone to snatch my diary out of my hands!

July 30, 1944

Tomorrow we’re leaving here, but we’ve no idea where we’re going. Destination unknown…

After the “diary”

Esther, Maurice and Menahem Pinto were deported on July 31, 1944 on Convoy 77, which was the last large transport from Drancy. According to their death certificates, all three of them were murdered in the gas chambers soon after they arrived at Auschwitz on August 3, 1944.

However, there is still some doubt about what happened to Esther: according to Father Carlotti’s testimony, she may not have died until May 15, 1945, in Parchim near Hamburg, in Germany. She may have been spared being sent to the gas chambers because she was old enough to work in the camp.

This is a plausible hypothesis, but there is no evidence to support it: according to the French civil status register, Menahem, Esther and Maurice Pinto were declared to have died on the date on which their train left for Auschwitz, on July 31, 1944. Unfortunately, we have no other records to go on.

This record contradicts Esther’s official death certificate, which states that she died on July 31, 1944. Note that the word “deceased” was initially preceded by “presumed”, and then the “presumed” was crossed out at some point. So, did she really die in Parchim? Source: © Arolsen archives

One thing that puzzled us during our visit to the Paris departmental archives was to find Menahem, Maurice and Esther’s names listed in the 1946 census, as if they were still there. No doubt the family was still hoping that all three would come home. Or maybe Grassia was afraid of losing the family home, who knows? The only difference between this and the pre-war censuses is that Menahem’s name is listed at the end, while Grassia is listed first, as “head of the family”. Also, the children’s names are listed in no particular order, with Mathilde listed right after her mother, whom she no doubt helped out with day-to-day tasks.

The 1946 census sheet for rue des Haies, including Menahem, Esther and Maurice’s names. Source: Paris departmental archives, ref. D2M8 942

In 1953, Grassia applied for Menahem, Esther and Maurice to be recognized as having been deported on political grounds. In addition, the words “died for France” were added to their death certificates. These applications show how difficult it was to prove that some members of the family were no longer alive, and the concierge of their apartment building had to complete a residence certificate for them (one for Esther and Maurice, as shown below, and a separate one for Menahem).

Residence certificate for Esther and Maurice. Source: file on Esther PINTO© French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy, ref. DAVCC 21 P 526 039

Grassia died in 1979. She was still living at 48bis rue des Haies in the 10th district of Paris.

Sources:

- File on Menahem Pinto, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref: 21 P 526 044

- File on Esther Pinto, idem: ref. 21 P 526 039

- File on Maurice Pinto, idem: ref. 21 P 526 043

The following records from the Shoah Memorial in Paris :

For Esther:

- Drancy camp internment records: FRAN107_F_9_5746_268310_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5746_268311_L

- Drancy camp transfer log: FRAN107_F_9_5788_0040_L

For Maurice:

- Drancy camp internment records: FRAN107_F_9_5746_268312_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5746_268313_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5746_268314_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5746_268315_L

- Drancy camp transfer log: FRAN107_F_9_5788_0040_L

For Menahem:

- 1940 census record: FRAN107_F_9_5657_066342_L

- 1941 census record: FRAN107_F_9_5622_020683_L

- Drancy camp internment records: FRAN107_F_9_5721_207723_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5721_207724_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5721_207725_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5721_207726_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5721_207727_L ; FRAN107_F_9_5721_207728_L

- Drancy camp transfer log: FRAN107_F_9_5788_0011_L

- Menahem’s name is on the list of people released from Drancy for health reasons in November 1941

- Menahem and Grassia Pinto asked the UGIF for help in 1943 (pages 155 and 156 of the pdf)

- The UGIF archives for the Secrétan center, digitized by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (series 5, section 52)

- Letter from Mr. Monteil to the Lucien de Hirsch school in May 1987, at the time of the Klaus Barbie trial, recounting the roundup at the Secrétan shelter through the eyes of a local child (©Lucien de Hirsch school archives)

- We visited the most interesting exhibition “Salonika, “Jérusalem des Balkans“, 1870-1920. Donation from Pierre de Gigord”, at the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris.

- We also visited the building where Esther and Maurice were arrested, the former UGIF Secrétan shelter, which is part of the Lucien de Hirsch school.

- For wartime newspaper front pages, we used the website: https://www.retronews.fr/

- We also referred to the following books:

– À l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, Annette Wieviorka and Michel Laffitte, collection Tempus, published by Perrin, Paris, 2012.

– Le Bosphore à la Roquette. La communauté judéo-espagnole à Paris (1914-1940), Annie Benveniste, published by L’Harmattan, Paris, 1989.

At the Shoah Memorial, were also able to access the « Aryanization » dossier for Menahem Pinto’s business.

Thanks:

We would like to thank Claire Stanislavski Birencwajg, documentalist for educational projects at the Archives Department of the Shoah Memorial, for her invaluable help in producing this project.

Thanks also to Jean-François Guillet, liaison teacher at the Paris departmental archives.

Lastly, many thanks to Shirly Elbaz, documentalist at the Lucien-de-Hirsch School, who kindly provided us with more records than we could have hoped for and who, together with Gilberte Raccah, took us on a tour of the building that housed the UGIF Secrétan center between autumn 1943 and 22 July 1944.

Français

Français Polski

Polski