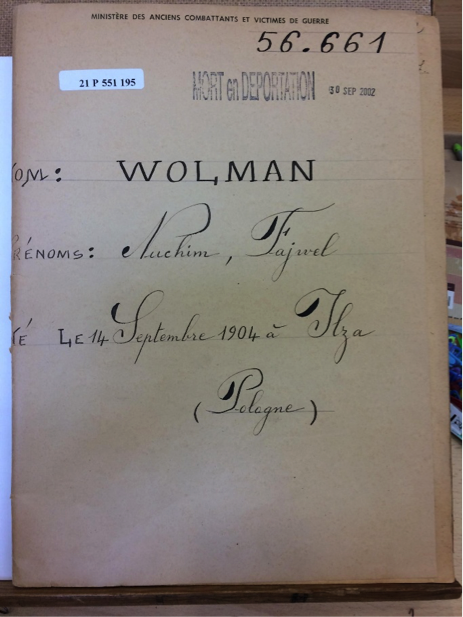

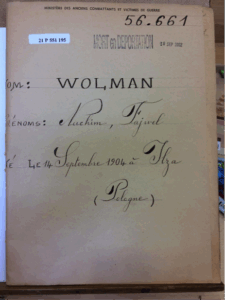

Nuchim WOLMAN

Among the 1,306 people deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 was Nuchim Wolman, a Jewish man from Poland. Our biography is based on applications for him to be granted “Deported Resistance fighter” and “Political deportee” status, along with a file on his membership of the F.F.I. (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur, or French Interior Forces), which are held at the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Vincennes and Caen.

© Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, dossier 16P 604178 © Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier 21 P 551 195

The requests were made by his wife, Rachel Kowalski, who he married in Dantzig, Poland, on August 2, 1932.

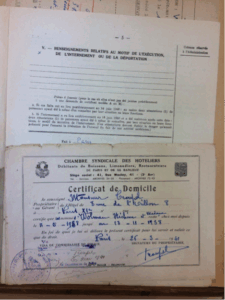

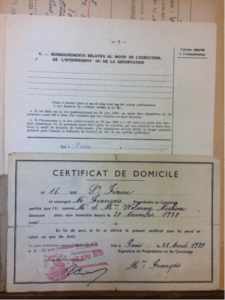

Nuchim Fajwel Wolman[1] was born on September 14, 1904, in Ilza[2], Poland. He held a bachelor’s degree[3] and earned his living as a hatter. We are not sure when the couple emigrated to France, but a residence certificate from a hotel owner in Paris confirms that the couple were living in Paris as of May 11, 1938[4]. Another certificate, this time from the building manager at 16 rue Saint-Fiacre in Paris, states that they moved there in late 1938.

Residence certificates © Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier 21 P 551 195

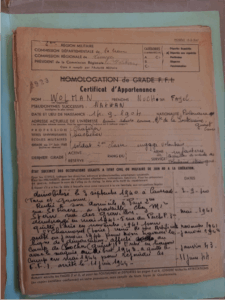

We know from his F.F.I. membership certificate that he had not been naturalized as a French citizen. He therefore kept his Polish nationality.

F.F.I. membership certificate © Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, dossier 16P 604178

Nuchim Wolman joined the one of the Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers, which were later incorporated into the French Infantry, shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, in September 1939. He was demobilized on September 3, 1940[5]. He then returned to Paris, but fled the city in November 1941 for the Loire department of France, where he found work in a factory.

In January 1942, he joined the French Resistance[6]. He belonged to the Front National de Lutte pour la Libération et l’Indépendance de la France (National Front for the Liberation and Independence of France), which was founded by the French Communist Party. He also joined the French Jewish Resistance movement, another Communist-based organization: the U.J.R.E. (Union des Juifs pour la Résistance et l’Entraide, or Jewish Union for Resistance and Mutual Aid). During his time with the Resistance, he was involved in anti-Nazi propaganda, including distributing pamphlets. Starting in mid-July 1943, he distributed clandestine publications at the Clocher camp[7] G.T.E. (Groupement de Travailleurs Etrangers, or Foreign Workers’ Group)[8], based at Guéret, in the Creuse department of France. Then, starting in February 1944, he began collecting weapons for an F.F.I. maquis (network)[9]. On June 11, 1944, he was arrested in Azat-Châtenet, also in the Creuse, during an attack on a German garrison, where he had been given the task of guarding 40 German prisoners. He was then interned in the Royallieu camp in Compiègne, in the Oise department of France, to which the majority of political prisoners were sent. Next, on July 6, 1944, he was transferred to Drancy, a transit camp for Jews north of Paris. He was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. It is not known exactly how or when he died.

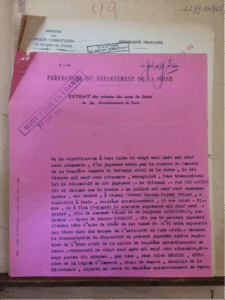

Death certificate, issued by the town hall of the 2nd district of Paris © Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier 21 P 551 195

Despite the fact that the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War recommended that he should be deemed to have died on August 5, 1944, in Auschwitz, the Seine Civil Court ruled that Nuchim Wolman died on July 31, 1944, in Drancy[10]. It is indeed difficult to determine the exact date on which a deported person died, as there is no way of knowing at what point in the deportation process it happened: on the journey, as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz, or during their time in the concentration camp. After the war, the French government decided that unless there was reason to suggest otherwise, they should be deemed to have died soon after the convoy arrived, so in the case of Convoy 77 this was August 5, 1944.

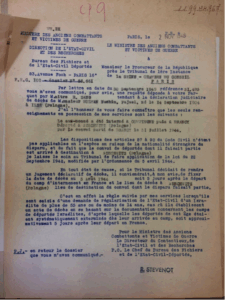

Letter from the Ministry for Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War dated November 2, 1949 © Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier 21 P 551 195

Nuchim Wolman’s widow, Rachel, applied for her husband to be posthumously granted the status of deported resistance fighter, which was refused on August 27, 1957, on the grounds that “the determining cause of his detention was not defined as an act of resistance against the enemy”, but rather that he was Jewish[11]. She then applied for him to be granted the status of political deportee, which was approved on May 13, 1958. His death certificate, dated September 27, 1950, bears the words “Mort pour la France” (“Died for France”). This was the French state’s tribute to the brave deeds that Nuchim Woman carried out as a Jewish foreign deportee in an attempt to liberate the country.

Nuchim Wolman’s name is inscribed on memorial in the Gerland Jewish cemetery in Lyon, in the Rhône department of France.

Notes & references

[1] His parents were Moszek Wolman and Frajndel Aibusiewicz.

[2] After 1942, when the ghetto where 2,000 Jews were assembled was destroyed, there was not a single Jew left in town: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I%C5%82%C5%BCa#cite_note-3

[3] As stated by his wife in the application form for the status of Deported Resistance fighter.

[4] A law passed shortly after the war stipulated that in order to benefit from any status, assistance, etc., it was necessary for a person to have been resident in France before war was declared – with the exception of anyone who had enlisted to fight against Germany. It was therefore essential to provide proof of a French address prior to September 1, 1939 (cf. letter dated February 17 in dossier 21 P 551 195. Note that the hotelier’s certificate is dated March 26, 1941. Nuchim must have needed it for a specific reason. To move to rue du Perche, perhaps? The certificate from the owner of the building on rue Saint-Fiacre, dated August 1939, may have been needed to enlist in the army. His wife also stated that when he was arrested in the Creuse department, his official address was 12 rue d’Hauteville, in the 10th district of Paris. One gets the impression that Nuchim had to move frequently for fear of being arrested. Did he register himself as a Jew at the police station, as required by the Vichy government legislation?

[5] In the Tarn-et-Garonne department. He then returned home to Paris, where he worked for a Mr. Stern on rue des Gravilliers in the 3rd district. In May 1941, he moved from his apartment in rue Saint-Fiacre to a new place not far from rue des Gravilliers, on rue du Perche.

[6] He was arrested in January 1942 for crossing the demarcation line that divided the occupied zone in the northern part of France from the Vichy-run “free” zone in the south. He was then sent as a “foreigner surplus to requirements in the national economy” to a labor camp for foreigners, the Clocher camp, a foreign workers group (40th – 863rd G.T.E.). As someone who had enlisted voluntarily, Nuchim should not have been interned at all: he was sent there because he had broken the law by crossing the demarcation line.

[7] The rules in these camps were fairly flexible, in that prisoners were allowed to go out into town and were sometimes housed with local people. It was while he was working there, in January 1942, that he first made contact with the Resistance.

[8] French Foreign Legion. Central Seine recruitment bureau. Serial number 15970. 1st military region. Shoah Memorial, Paris. Union des Engagés Volontaires, Anciens Combattants Juifs (The French Union of Volunteers and Jewish War Veterans) records.

[9] On June 6 he was under the command of Lieutenant Colonel François.

[10] This was a convention for all deportees whose fate was not known, according to certain criteria: age, health, etc. His date of death was rectified by a decree dated October 25, 2002, and recorded at the town hall of the 2nd district of Paris on January 20, 2004. Many people were declared to have “died in Drancy”, often in order to facilitate the necessary administrative procedures for the families concerned.

[11] His widow, however, provided a valid certificate, although the reason for his arrest was not stated. The words “Died in deportation” were also added to the margin of his death certificate. Nuchim Wolman’s name is inscribed on memorial in the Gerland Jewish cemetery in Lyon.

Français

Français Polski

Polski