Anna TASIEMKA, 1930-1944

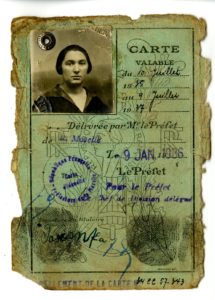

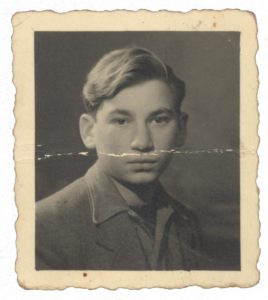

A photograph including Anna Tasiemka.

Source: Shoah Memorial in Paris/Serge Klarsfeld collection

This biography of Anna Tasiemka is an extract from the web documentary in French: “Convoi 77: Sur les traces de la famille Tasiemka” (Convoy 77: Following in the footsteps of the Tasiemka family, it is available at convoi77-tasiemka.fr

INTRODUCTION

Our project for Convoy 77 involved three 9th grade classes, A, B and G, at the Eugène Fromentin junior high school in La Rochelle, France. This included seventeen students aged 14 and 15.

We were made aware of the project via the school’s website in June 2020.

We were told that we could join the working group by answering a few questions, which were intended to assess our interest in the project.

What attracted us most was the time frame in question, as well as the documentary and research work about a real family.

The objective of the project was to research all the comings and goings of the Tasiemka family. For this reason, we worked in partnership the FAR, (Fonds Audiovisuel de Recherche , or Audiovisual Research Foundation), at La Rochelle, with whom we made a web documentary.

Our joint aim was to reconstruct the story of the Tasiemka family, which was plunged into the turmoil of the Holocaust.

-

THE TIMELINE OF THE RESEARCH

During our first working group session, on Tuesday, September 22, 2020, we learned about the Convoy 77 project and how it came about.

The project was initiated by Georges Mayer, whose father, along with more than 1300 other men, women and children, was deported on Convoy 77 from Drancy to Auschwitz, where the majority were murdered by the Nazis. In addition to paying tribute to the victims, the main objective of the project is to restore the identities of people who were persecuted, insulted and dehumanized during the genocide of the Jews and Gypsies by studying the Shoah in a non-conventional way, and learning from the experience.

To this end, Mr. Mayer created a website, https://convoi77.org/ , on which school teachers can choose from the list of Convoy 77 deportees a person or a family that they would like to work on. Then, together with their students, they write a biography of that person or biographies of all the family members.

To date, Serge and Beate Klarsfeld and the Shoah Memorial have researched about 400 deportees, but the stories of some 900 deportees remain untold. The victims’ origins are many and varied, involving more than 37 different countries. The Convoy 77 project is therefore a Europe-wide initiative.

We, the students from the Eugène Fromentin school, were unable to find any deportees from La Rochelle on the Convoy 77 list. However, we were interested to discover the Tasiemka family, with four children of similar ages to ours, who had once lived in our department and met a tragic fate under the barbaric Nazi regime.

The first working group session also enabled us to find some initial information about the Tasiemka children: Adolphe, Anna, Marie and Régine. The Convoy 77 project website provided us with their respective dates and places of birth: February 11, 1929 for Adolphe, November 19, 1930 for Anna, May 11, 1932 for Régine and October 17, 1937 for Marie. All the children were born in Metz, in the Moselle department of France, but the address listed as Avenue de Bordeaux in Royan showed that they were no longer living in Metz during the war. Finally, we learned that the four children were arrested at the Secrétan children’s’ home in Paris, which was run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) before being deported on the last large convoy to Auschwitz. With so little information and so much to research, we realized the magnitude of the task at hand.

Were we discouraged? Definitely not! During the second session, we searched the Shoah Memorial website for clues and finally discovered two photographs of the Tasiemka children. The first is a portrait of Adolphe and the second is a group photo in which we can see Anna, with a group of other children, on which the name “Eva” is written in one corner.

This discovery raised new questions for the group: who was ” Eva”, would she have survived the Holocaust? If so, might it have been her children who put the photograph online? What links could Anna have had with this young girl? Too many questions and so few answers for the moment. In addition, the Shoah Memorial website showed us that the various members of the Tasiemka family did not all follow the same path. In fact, Pessa and Abraham Leib Tasiemka were deported on Convoy 46 on February 9, 1943, about a year and a half before Convoy 77 took their children to their deaths. Our working group explained this difference by the fact that the parents were considered to be “stateless” whereas Adolphe, Anna, Régine and Marie were French citizens. Through the places mentioned, such as Drancy, we were also able to begin to draw a rough outline of the Tasiemka family’s journey: Metz – Royan – Drancy – Auschwitz. As the work progressed, a chronological table allowed us to sort out the information.

However, the information available from the Shoah Memorial was incomplete. Our teachers therefore referred us to some other databases. The first, held by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Israel, added to the complexity of our investigation, especially as regards Adolphe, since it the site mentioned that he had been interned in the Poitiers camp in the Vienne department, whereas his sisters had been sent to Segonzac, in the Charente department.

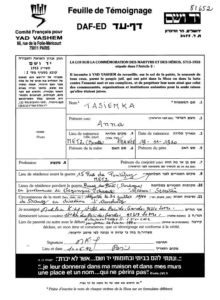

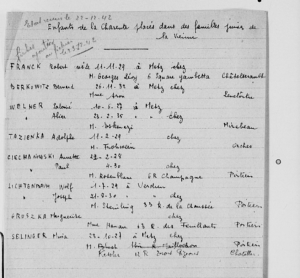

A document found in the Yad Vashem database

Why were the siblings separated? This was yet another question to be addressed in the course of our research. Then in the Gallica database, the name Tasiemka led us to a bibliographic reference, a book by Paul Lévy entitled “Un camp de concentration français, (a French concentration camp), 1939-1945“. Finally, Serge Klarsfeld’s, Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the deportation of the Jews of France) made available online thanks to the work of Jean-Pierre Stroweis, enabled us to confirm our sources once again and to add one of the most important pieces of information to our chronological table: the exact death date of the Tasiemka children. All four of their names are listed in an extract from the French official bulletin of May 21, 2011, and each includes the words “mort en deportation”, or “died during deportation”.

(Extract from the French official bulletin dated May 21, 2011)

JORF n°0118, May 21, 2011

Text n°53

Order of March 25, 2011 concerning the addition of the words “Died in deportation” on death certificates and declaratory judgments

NOR: DEFM1109792A

By order of the Director General of the National Office for Veterans and Victims of War dated March 25, 2011:

- – The words “Died in deportation” are entered on the death certificates and declarations of death of:

Rosenberg, born Rosenberg (Szajndla, also known as Jeannette) March 21, 1920 in Bedzin (Poland), died August 5, 1942 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Rozner (Herman), born October 31, 1932 in Nancy (Meurthe-et-Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Ruiz-Vivar (Juan, Antonio), born June 26, 1910 in Aldeaquemada (Spain), died October 21, 1942 in Gusen (Austria).

Schumann (Charlotte), born January 12, 1931 in Metz (Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Szwalberg (Madeleine), born November 20, 1936 in Paris (12th district) (Seine), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Tasiemka (Adolphe, Samuel), born February 11, 1929 in Metz (Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Tasiemka (Anna), born November 19, 1930 in Metz (Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Tasiemka (Marie), born October 17, 1937 in Metz (Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Tasiemka (Rachel), born May 11, 1932 in Metz (Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Wajnryb (Edouard), born August 11, 1939 in Neuilly-sur-Seine (Seine), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

Wietrzniak (Paulette), born September 13, 1931 à Metz (Moselle), died August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

The next step in our investigation was to contact the various archives departments that could send us documents about the Tasiemka family. Despite the Covid situation, the Charente Maritime Departmental Archives office welcomed us warmly on December 3, 2020 for a meeting with Mr. Petitclerc, who is in charge of the educational service, and who kindly helped us in our research and agreed to take part in an interview with our partner, the Audiovisual Research Foundation of La Rochelle. We were thus able to see with our very own eyes the family’s original civil status records, which were placed under glass due to their fragility. The first part of the afternoon was devoted to analysis of the archives in sub-groups, learning about methodology and seeing the faces of Pessa and Abraham Leib for the first time on their identity documents.

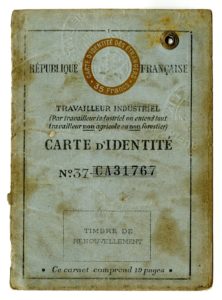

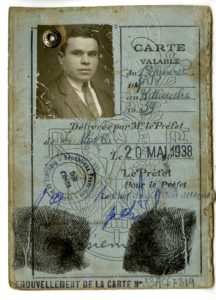

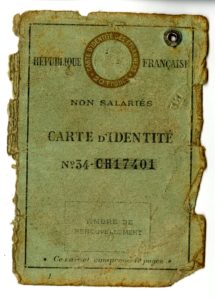

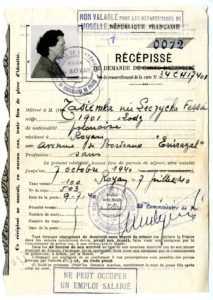

Abraham Leib and Pessa Tasiemka’s identity cards, from the Charente-Maritime departmental archives.

Extract from Passa Tasiemka’s request for renewal of identity documents, put together in Royan, from the Charente-Maritime departmental archives.

In addition, some new clues about parents “appeared”, such as their date of arrival in France: Abraham Leib arrived in Verdun in 1921, and Pessa followed in 1926. We concluded our visit with a guided tour of the premises led by Mr. Petitclerc.

As our timeline was filling up, we were eager to contact the Moselle Archives service. Two students from our work group volunteered to write to them, and sent the following email:

“Dear Madam,

We are students at the Fromentin College in La Rochelle and we are participating in the Convoy 77 workshop organized by our History and Geography teachers, Mr. Raguy and Mr. Supervie. As we are currently researching the story of the Tasiemka family from Metz, who were deported during the Second World War, we are interested in any information you have (especially postcards) about the Jewish quarter of Metz, as well as any other documents that could help us with our research. You can send documents via this e-mail address or on paper to the following postal address Collège Eugène Fromentin 2, rue Jaillot 17000 La Rochelle,

Thank you in advance for your help,

Yours sincerely,

Simon & Solal”

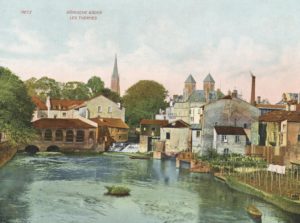

In reply to this mail, the Moselle departmental archives service sent us some postcards of Metz and an article about the city before the Second World War by Patrick. J. Scheffer and entitled “La question du repliement exceptionnel de l’agglomération messine (The question of the extraordinary decline of the Metz agglomeration (1937-40)”.

Postcard of Metz kindly provided by the Moselle Departmental Archives ref:/ 24FI811: View of the thermal baths district and the Moselle, Pontiffroy: color postcard.

Postcard of Metz kindly provided by the Moselle Departmental Archive, ref:/ 8FI463/1017: Metz. König Johann-Kaserne. Caserne Chambière. [1907]

We also obtained copies the children’s birth certificates by making an online request on the Metz Municipal Archives website.

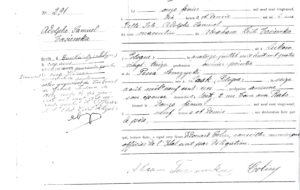

Anna Tasiemka’s birth certificate, Metz Municipal Archives

As previously mentioned, it is important to recall the context of the Tasiemka family’s way of life and the obstacles that hindered their journey. For this reason, our teachers contacted various other archive services to request further records, such as the Departmental Archives in the Dordogne, Charente and Vienne departments and the Bobigny Municipal Archives service.

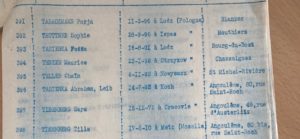

During our investigation, we happened up some other useful information. While we were browsing through the biographies posted on the Convoi 77 website, we came across the work of a history teacher, Bruno Mandaroux, and his students at the Louis Vincent high school in Metz, who had written about the life of Charlotte Schumann. The archived documents included caught our attention and it was with much emotion that we read the names of the three Tasiemka sisters.

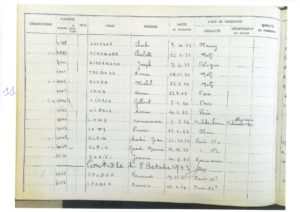

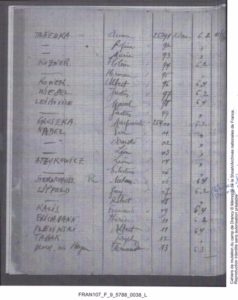

Register of arrivals at Louveciennes on September 3, 1943 – Shoah Memorial archives

We felt compelled to get in touch with him. We did not know at the time, but this contact proved to be essential. Bruno Mandaroux was kind enough to go to the Municipal Archives service in Metz on our behalf to retrieve some documents that we already suspected must exist, having read an article that had been sent to us by the Moselle Archives service. However, we had been unable to obtain them ourselves because they could only be viewed on the premises.

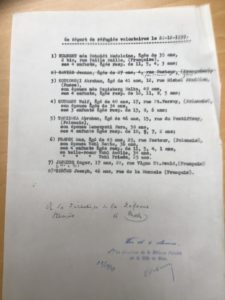

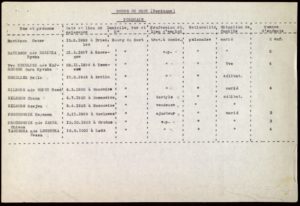

Official report of the 6th convoy of voluntary evacuees to Charente-Inférieure, dated December 22, 1939 – Metz Welfare Bureau, Metz Municipal Archives.

He also provided us with some other important material, the result of further research with his students, which is included in our web documentary.

Another highlight of our research work was our meetings with witnesses and historians who were willing to help us with our task. In the village of Bourg-Du-Bost, in the Dordogne department, the staff at the town hall knew of an elderly resident, a Mr. Morillère, who had been a witness to the Tasiemka family’s stay in their town. This news was met by great surprise and excitement within the group. Emma’s big eyes shone; she could hardly believe it. We had never imagined that we might be able to work with a real-life witness who had known the Tasiemka family for almost eight months! Our teachers also invited Bernard Reviriego, historian and author of the book “Les Juifs en Dordogne 1939-1944” (The Jews in Dordogne, 1939-1944) prefaced by Serge Klarsfeld, to accompany us during this meeting. Our trip to the Dordogne took place at a time when there were a lot of floods in the southwest of France. We were quite worried on that Thursday, February 4, 2021, about the worsening Covid situation and the rising water levels. However, despite these challenges, the day went ahead as planned and, with the help of Benjamin Mohr of the Audiovisual Research Foundation, we were able to meet and interview Mr. Morillère and Bernard Reviriego, the historian.

As for the Royan side of things, some research that we had hoped to carry out was impossible due to the Covid 19 situation. We had planned a meeting with Ms. Debette, the manager of the Royan museum and Ms. Marie-Anne Bouchet-Roy, author of the book “Royan 39-45, guerre et plage” (Royan 39-45, war and beach) in order to gain a better understanding of what happened in Royan during the war. At the time of writing, the beginning of April 2021, the trip to Royan has still not been possible but we continue to hope for better days.

To help complete and enhance our biographies and to gather further information, the name of Robert Frank, a Holocaust survivor who was mentioned frequently in the archives, came to mind. We made contact with him and arranged a meeting, during which he would be able to tell us his story, which was almost identical to that of the Tasiemka children. We were therefore very disappointed when, just two days before the meeting, it was announced that inter-regional travel was prohibited for people coming from areas most affected by the pandemic. This meant that he could not come to the Eugène Fromentin school to tell us his story. However, we are still in contact with Mr. Frank who wrote to us as follows

“I have had the two anti-Covid injections and am waiting for the end of the lockdown in the Ile de France region so that I can travel outside of Paris again. I still hope to be able to meet you soon.

Yours sincerely,

Robert Frank”

To conclude this first part of the biography, our teachers express their thoughts and highlight some of the difficulties and obstacles encountered:

There were several types of difficulties. The first was working with and familiarizing 9th grade students with the work of an investigator-historian, of which they had no previous experience. Students are more accustomed to being provided with complete and detailed information, whereas here they were confronted with the task of a researcher. However, we found that the students, who had volunteered for the project, were well motivated. The students sometimes found working with the sources challenging: deciphering and understanding administrative documents were some of the difficulties.

At one point, an archived record from the post-war intelligence service also made us doubt our sources, and we had the students question the reliability of certain documents and the necessary cross-checking of information in order to try to uncover the truth.

The documents are also limited by what they do not say… The students thus learned that the archives do not provide all the details needed to trace the itinerary of a family during the war, and thus there might be some “gaps” in the chronology. We therefore had to make comparisons with survivors’ testimonies and with the stories of other people who had followed almost the same path as the Tasiemka siblings.

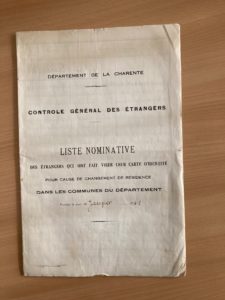

In addition to these methodological questions, there were other difficulties, in particular access to sources. For example, some archives departments were unable to provide us with the requested sources, such as that in Charente, which informed us that “the 1 W 41 series is currently inaccessible because it is in the process of being classified”.

The limitations also include the questions that remain unanswered… For example, after retrieving two photographs of Adolphe and Anna Tasiemka from the Shoah Memorial website, we wanted to establish contact with the person who had submitted the photograph of Adolphe. Here is an extract of the letter we sent:

“ …. On the Shoah Memorial website, we found the photograph of Adolphe Samuel Tasiemka that you submitted. To quote Daniel Mendelsohn, from his book “Les disparus” (The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million), “It’s different to write the story of people who survived because there is someone to interview, and they can tell you these amazing stories […]. My problem […] is that I want to write the story of people who didn’t survive. People who had no story anymore.

With your help and support, we would like to give our students the opportunity to rediscover this history, that of the Tasiemka family and that of Adolphe Samuel in particular, to record their singularity and uniqueness in the tragedy of the Shoah. We thank you in advance for all the invaluable information that you may be able to share with us in order to continue our memorial project.”

Photograph of Adolphe Samuel Tasiemka – Shoah Memorial

The mystery of this photograph, as well as the photograph of Anna, remains unsolved. Sometimes we have to come to terms with such silences. In the same vein, we asked Jeannick Weyland of the GREH (Research and Historical Studies Group) of Charente Saintongeaise to carry out some research in Segonzac, to try to find any records attesting to the presence of the Tasiemka sisters in the village, but to no avail.

The final pitfalls we encountered were those resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic. Indeed, we were unable to complete our investigation, as we would have liked to accompany our students to different memorial sites, such as the Shoah Memorial in Paris, Drancy and the site of Bobigny train station, from which Convoy 77 departed.

-

THE WRITING OF THE BIOGRAPHIES

Metz

The arrival of the Tasiemka parents in France

Our investigation enabled us to find some background information about the Tasiemka parents.

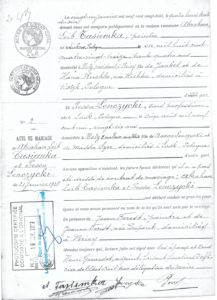

- Abraham Leib Tasiemka was a Polish Jew born on July 14, 1893 in Kock, Poland. He was the son of Jankel and Richter Stana Ruchla Tasiemka. In Poland, he was a painter and decorator, a profession that he continued in France. He was thus of Polish origin and as such, after emigrating to France, he was considered to be a stateless person. He arrived in Verdun, France in 1921 and married Pessa Lenczycka, a Polish Jew, on January 21, 1928 in Briey, France.

- Pessa was born in Lask, Poland on August 16, 1901. She arrived in France in 1926. She was 26 years old when she got married. She did not work outside the home and lived with her husband at 2, Tour-aux-Rats in Metz.

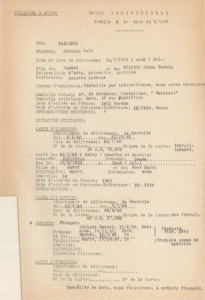

Personal record sheet drawn up in Royan on 6 September 1940, Charente Maritime Departmental Archives

The Tasiemka’s marriage certificate, from the town hall in Briey

The Tasiemka couple had no children when they fled Poland. What reasons might have prompted them to leave? Why did they choose France?

There are no records to explain this. An article by Alban Perrin, “Comment devient-on français quand on est juif et polonais ? Itinéraires comparés de rescapés de la Shoah” (How does one become French when one is Jewish and Polish? Comparative itineraries of Holocaust survivors) does however give us a few points of reference.

Several reasons may explain their move:

First of all, the Jews were subjected to increasing anti-Semitism in Poland.

They could have chosen to go to France because it was a very rich and powerful country, especially for Europe, and also had great military strength.

Also, they saw France as a land of freedom, where human rights were very important.

Lastly, many Polish Jews were not particularly attached to Poland.

We have been unable to contact the Polish archives office. The story of the Tasiemka parents’ time in Poland therefore remains unwritten.

4 children born in Metz

Birth certificates include information on all four Tasiemka children:

- Adolphe Tasiemka was a French Jew, born on February 11, 1929 in Metz

- Anna was also born in Metz, on November 19, 1930

- Régine Tasiemka was born on May 11, 1932 in the same town as her older brother and sister

- Marie was the youngest, born on October 17, 1937

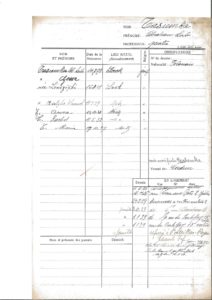

Thanks to an address record, we were able to track where they lived:

- 17 rue Chambière

- 15 rue du Pontiffroy

Abraham Leib Tasiemka’s address record, Metz Municipal Archives

To better understand their early days in Metz and the environment in which they lived, another article, “André Schwarz-Bart et la ville de Metz” (André Schwartz-Bart and the city of Metz) by Jean Daltroff, published in 2012 in the magazine “Les Cahiers lorrains” is helpful.

The Jewish population of Metz made a huge jump. From 1910 to 1931, it increased from 1691 to 4147 and by 1939, the Jewish community had grown to 4200. The Pontiffroy district of Metz was where most of the Jews lived. Their professions varied widely, from carpenter to house painter to shoemaker. The Tasiemkas could have rubbed shoulders with some of the well-known Jews in these fields, such as Léon Wladimirski, a tailor, Lewek Lancman, a painter, and Hirsch Gowitsch, a fitter.

A postcard from Metz kindly provided by the Moselle Departmental Archives department, ref /8FI463/1493: Metz. General view /View of the Pucelle dam, roofs of the Chambière island district, Protestant church of the garrison on the right

The departure from Metz

The Tasiemka family left Metz on December 22, 1939. To help us understand the circumstances in which the people of Moselle left, we studied another article entitled “La question du repliement exceptionnel de l’agglomération messine” (The question of the exceptional withdrawal of the Metz conurbation), by Patrick. J. Schaeffer.

“On November 22, 1937, the Prefect of Moselle announced to the Mayor of Metz that in order to protect the population from the risks of war, the government had planned an “emergency evacuation” of his city.

On September 1, 1939, the evacuation began. The first people to be evacuated were those who were sick in hospitals and then, on September 9, it was the turn of the elderly, women and children.

During the month of September, nearly 6,500 people from all neighborhoods voluntarily left Metz by train or in special wagons. Then, as the threat of war seemed remote, the exodus slowed down.

However, between December 1, 1939 and March 26, 1940, there were 19 evacuation operations, which took place weekly, involving more than 550 people. The registration lists show that there were far more foreigners, almost exclusively from Central Europe or stateless people, than French people. Each departure grouped 7 to 15 families, 30 to 50 people in all, the vast majority of whom were children.”

Robert Frank and his family were on the train that left Metz on December 22. Thanks to his testimony we can relive the journey. He said that when they boarded the train, “everyone received a Camembert cheese and 5 francs”. The train then went through Paris on its way to La Rochelle. The Frank family and the Tasiemka family met up once again in Royan.

Royan

The family’s arrival in Charente-Inférieure

Photograph of Royan during the ’Occupation, Charente-Maritime Departmental Archives

The documents found in the Charente Maritime departmental archives mention date of the Tasiemka family’s arrival in the Charente-Inférieure (a department in the west of France, now called Charente-Maritime).

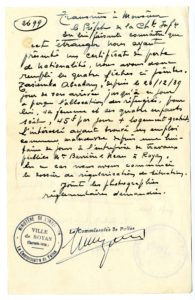

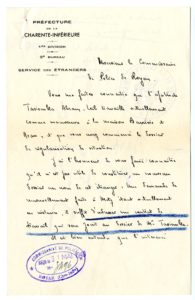

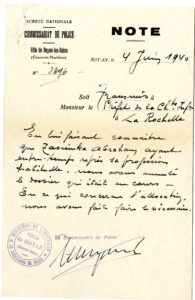

Letter sent in 1940 from the Royan police department to the prefect of Charente-Inférieure, from Abraham Leib Tasiemka’s application to renew his identity papers – Charente-Maritime Departmental Archives

They arrived on December 23, 1939. How did the Tasiemka family feel about the move to Royan? How were they and the other people from Moselle received by the locals?

Patrick J. Shaeffer’s article again contains some valuable information:

The refugees from Metz seem to have had a difficult time integrating. They were emotionally upset by their relocation; “the refugees have the blues”. The living conditions of the refugees were also a problem. In terms of schooling, for example, “the situation is the most delicate in Royan, where two teachers have to take care of the four new classes that have been put in place”.

Life in Royan

What exactly do we know about the life of the Tasiemka family in Royan?

Letters exchanged between the prefecture of the Charente-Inférieure and the Police Commissioner give us some insight.

Documents from Abraham Leib Tasiemka’s application to renew his identity papers, Charente-Maritime Departmental Archives

Abraham Tasiemka received a refugee allowance for himself and his family, as well as free housing:

- The amount of the allowance was 45 French francs a day.

- Their address was Villa Emirazal, Avenue de Bordeaux, Pontaillac, in Royan. Since Royan was a resort town, most of the villas were vacant at that time of the year.

Plan of Royan, from the French website, Géoportail

Abraham lost his allowance as soon as he found a job as a painter with a construction company, Maison Barrière et Neau, in Royan. He was recruited on May 20, 1940. His salary was 6 francs an hour.

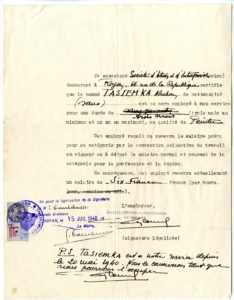

Statement signed by the employer and the mayor on July 15, 1940 certifying that Abraham Tasiemka had been employed as a painter in the company since May 20, 1940 – Charente-Maritime Departmental Archives

To better understand what the Tasiemka children experienced during their stay in Royan, it is worth referring to Robert Frank’s testimony. He was a Jewish child of a similar age to the Tasiemka children who left Metz on the same train as them and was also sent to Royan. We suppose, therefore, that there were many similarities between Robert Frank’s story and that of the Tasiemkas.

His account in the book “Les enfants du silence, mémoire d’enfants caches” (The silent children, memories of the hidden children) helps us understand what Adolphe, Anna, Régine and Marie went through. “Our family ended up in Royan. We stayed there for eleven months. After the Germans arrived in June 1940, I worked as a translator in department stores in the town. One day, a skinny Nazi with an emaciated face and glasses asked me “how I knew German”. I told him I was from Lorraine. He said, “You are a Jew”. I ran away and I was very scared.”

In addition to Robert Frank’s testimony, what do we know about the fate of all the Jewish families in Royan at that time?

An article written by William Guéraiche entitled “Administration et répression sous l’Occupation : les « Affaires juives » de la préfecture de Charente inférieure” (Administration and repression during the Occupation: the “Jewish Affairs” department of the Prefecture of Charente-Inférieure), includes the following:

“At the time of the first census in October 1940, the Jewish community was estimated at 1218 people. Most of the Jews who were in Charente-Inférieure when the occupying troops arrived were some of the 13 or 14,000 refugees, the vast majority of whom came from Alsace-Lorraine.”

“The commissioner of Royan, who tallied up the numbers on October 17, 1940, counted 88 families in the area, including 51 foreign families. They all came either from Turkey (Constantinople) or indeed from Central Europe.”

The time came to leave Royan

A visa kept in the Charente Departmental Archives mentions Abraham’s transfer from Royan to Angoulême on November 14, 1940.

On November 23, 1940, it was his family’s turn to leave.

Census record, Royan Town Hall, December 1940, Charente-Maritime Departmental Archive

This move took place for a specific reason. All Jews were obliged to leave the Atlantic coast, which had been declared a “no-go zone” for them. They could only take the bare minimum of belongings with them.

From Royan to Bourg-du Bost

The Charente Departmental Archives provide us with some information about the Tasiemka family’s journey after they left Royan.

Documents from the series 2 W 37 and 2 W 38, Charente Departmental Archives

After leaving Royan, the Tasiemka family first stayed in Angoulême, where they lived at 80, rue St-Roch. They then settled in Bourg-du-Bost. Pessa arrived first, perhaps with the children, followed by Abraham on January 18, 1941.

The Tasiemka family’s time in Bourg-du-Bost

Postcards of Bourg-du-Bost, Source: Munoche collection, cartespostalesancennesperigord website

There were several Polish families in the village, such as the Kilbergs: Rosa, from Sanowice, Chana, a typist, from Sosnowice, and Ozejwa, a saleswoman, from Bosnowice, and the Prochowniks: Heymann, a fitter from Woclawec, and Chiena, from Grodno. In total, in all these families, there were 22 children whose parents came from Poland.

Census form for foreigners in the municipality of Bourg-du-Bost, Dordogne Departmental Archives

What was everyday life like for these children in the Dordogne? We can get some idea from the account of Robert Frank, who lived about 5 miles from Bourg-du-Bost, in the village of Festalemps. Mr. Frank and his family lived in an abandoned farm, which was empty, dirty, full of cobwebs and had no electricity. They were provided with the bare minimum to survive, and the parents worked hard to make the farm habitable. They seem to have been left in peace however, and continued to practice their religion.

However, decrees aimed at excluding Jews from society continued to be issued, resulting in the obligation to wear the yellow star as of June 1, 1942. Then, during the night of October 8 to 9, 1942, the gendarmes woke up the families and ordered them to get in a truck that arrived an hour later. In it were 7 of the 10 Jewish families who had arrived in Angoulême in 1940.

A second account, that of Mr. Morillère, then a child in Bourg-du-Bost, brings us even closer to the Tasiemka family. He remembers that Abraham Tasiemka worked at home as a tapestry maker. He was at school with the last three children, Anna, Marie and Régine. He says that two policemen came to arrest the parents and that before leaving the village, Abraham went to say goodbye to his father. He still has a very positive memory of the family, whom he describes as being well-liked by everyone. The parents may have been among those arrested during the night of October 8-9, 1942, but the children were not arrested at the same time. Many uncertainties still remain. The Charente Departmental Archives have not yet revealed all their secrets.

The Vienne department

The Vienne Departmental Archives help us to retrace the steps of the Tasiemka family.

The parents’ journey

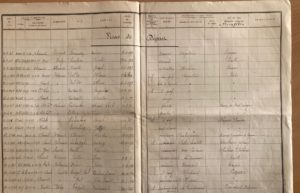

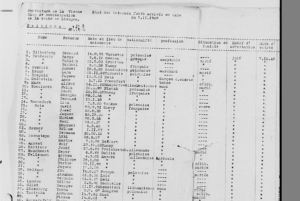

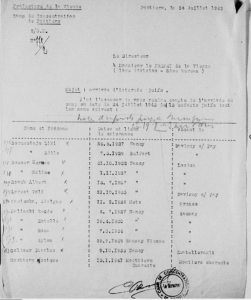

A document from the Vienne prefecture entitled “Etat des internés Juifs” (Report on Jewish internees) dated November 7, 1942, mentions their presence in the concentration camp on the Limoges Road in Poitiers.

Document from the series 109 W 17, Vienne Departmental Archives

We can see the date they entered the camp, October 7, 1942, and the reason for their arrest: “Jew”. From another document, we learn that they left the camp on November 12, 1942 and were transferred elsewhere

Document from the series 109 W 17, Vienne Departmental Archives

What we know from the Shoah Memorial website and an extract from the French official gazette dated February 18, 2017, is that they were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 46, on February 9, 1943 (see frieze), and murdered on arrival on February 14, 1943.

Adolphe Samuel Tasiemka’s journey

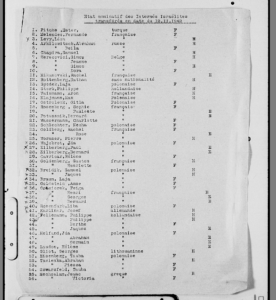

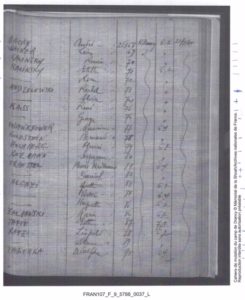

The first step in Adolphe Tasiemka’s journey was when he arrived in Orches, northwest of Châtellerault, at the end of December 1942. He was placed with a Mr. Frohwein. He is mentioned on a list of the children who arrived from Charente and were placed with Jewish families in the Vienne department.

Document from the series 109 W 17, Vienne Departmental Archives

The names of eleven children are listed, including Robert Frank. The reference to the Charente as the place he came from suggests that Adolphe did not arrive in the Vienne directly after leaving Bourg-du-Bost. He then stayed with Mime Levy in Orches.

The second stage of his journey was his arrival at the Poitiers camp on July 24, 1943.

Document from the series 109 W 17, Vienne Departmental Archives

The Poitiers camp had been open since September 1939. At first, it was used to house foreigners, in particular Spanish refugees, then gypsies, and then Jews who had been arrested.

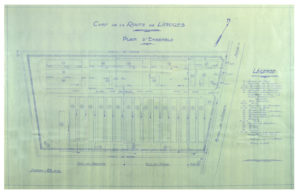

Plan of the camp on the route de Limoges in Poitiers in the spring of 1942. This engineer’s plan, with measurements and notes, shows the work carried out, the work in progress and the barracks that could potentially be built. It also shows the locations of the ditches covered with duckboards and the work needed to clean up the camp, which was on a clay plateau where rainwater stagnated, making it muddy. Record: 109W215, Vienne Departmental Archives.

Photographs of the Poitiers camp taken in December 1941. Record 109W219, Vienne Departmental Archives

What were the living conditions like for the internees? How can we find out what the Tasiemka parents, and later Adolphe, experienced during their time in the Poitiers camp?

Two texts helped us to understand a little better what they experienced. They are the book “Un camp de concentration français: Poitiers” (“A French concentration camp: Poitiers”) by Paul Lévy and the testimonial of Félicia Barbanel-Combaud on the INA website: “Grands entretiens-Mémoires de la Shoah” (“Important Interviews – Memories of the Shoah”).

In the camp, the internees were crammed into overcrowded barracks. Sanitary conditions were very poor and conducive to disease due to the presence of rats and mice and a lack of soap for washing. They did not even have mattresses or beds, so they had to sleep on straw on the ground with only a few blankets. Inside the camp, the gypsies helped the Jews. In the early days, they made music to get the younger ones to dance. Later on, they even arranged mock fights, which gave a few Jewish children a chance to escape.

How long did Adolphe stay in the Poitiers camp?

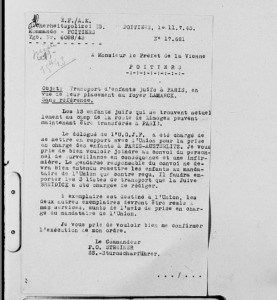

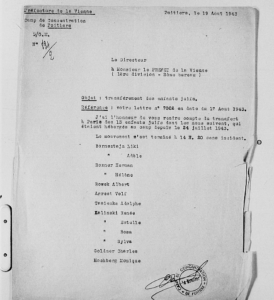

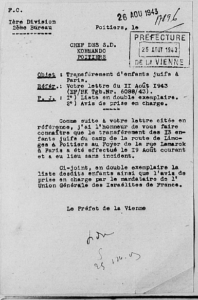

Further documents, in particular letters exchanged between the Prefect of Vienne, the director of the Poitiers camp and the German authorities, help us further.

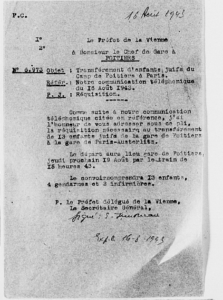

On 19 August, Adolphe was transferred to Paris by train along with twelve other children. The manager of the Poitiers camp wrote to the Prefect of the Vienne department: “The transfer ended without incident at 2.20 p.m.”.

This transfer was very well-organized. As few people as possible had to be told about it, and security was tight. Adolphe went from the Poitiers camp to the station by bus.

The station had to arrange “freight cars” to transport the Jews. Between 24 and 48 hours after the order from the German authorities, they were ready to begin the transfer. When the train arrived, the State Police took over from the Poitiers gendarmes. The children were sometimes sent to children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews). This was what happened to Adolphe, who was sent to the Lamarck center in the 19th district of Paris.

Documents from the series 109 W 17, Vienne Departmental Archives

Although the journey of Adolphe Tasiemka and the parents is well-documented in the Vienne Departmental Archives, there is no mention of Anna, Régine or Marie.

The UGIF children’s homes

The UGIF archives provide us with the opportunity to trace the Tasiemka sisters. But what exactly was the UGIF?

A brief description of the UGIF

The Union Générale des Israélites de France, (UGIF), the Union of French Jews, was founded by a law passed by the Vichy government on November 29, 1941. “The UGIF’s mission is to ensure the representation of Jews in dealings with the public authorities”.

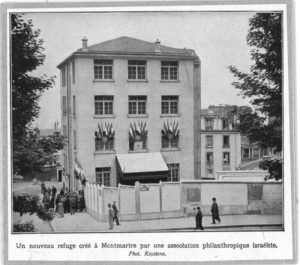

The UGIF children’s homes were established in the second half of 1942 to accommodate children whose families had been deported. Among them was the Lamarck center in Paris.

Photograph of the Lamarck center, photo © mahJ

An article by Jean Laloum entitled “L’UGIF et ses maisons d’enfants: le centre de Montreuil-sous-Bois” (The UGIF and its children’s homes: the Montreuil-sous-Bois center) tells us a little more:

“The supervisors and social workers in the centers were afraid that a roundup was imminent. The list of U.G.I.F. centers, along with the number of residents, requested some time earlier by the commandant of the Drancy camp, SS Brunner, had only increased their fear.”

The Tasiemka children at the Lamarck center

The Tasiemka sisters arrived at the center on June 9, 1943.

Register of arrivals at the Lamarck center, Shoah Memorial archives

According to the records, they had come from Segonzac rather than from Bourg-du-Bost. On September 3, 1943, they were sent for a spell in Louveciennes, in the countryside outside Paris, to improve their health. They returned to the Lamarck center during the month of October. We have very little information on Adolphe Samuel, however, other than his inclusion in the police register for the Lamarck center, where we find the date on which he arrived, August 20, 1943, and the date he left, September 2, 1943.

Page of the police register for the Lamarck center, from the Jewish Center of Montmartre archives.

The children at the Lucien de Hirsch center, on Avenue Secrétan

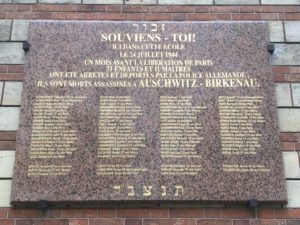

The children had to leave the Lamarck center because during the night of April 20, 1944, there was a massive bomb attack on the Montmartre district of Paris. Bombs of more than 5 tons fell in rue Chevalier, right next to the center. The children left during the night for the Secrétan school, which took them in because the Lamarck center building was no longer safe. They stayed there until July 21. Between July 20 and 24, in the middle of the night, roundups took place in several children’s homes in the Paris area, including the Secrétan center.

Joseph Niderman, who was 13 years old at the time of the raid, recalls the roundup in his testimonial:

“That night, again they did it before daybreak, at two o’clock in the morning. It was all done covertly. Buses arrived on avenue Secrétan and all the sleeping children were picked up indiscriminately. No papers were asked for, nothing at all…. We were taken straight to Drancy on those notorious buses with open platforms at the back.

Drancy and Bobigny

A short introduction to the Drancy camp

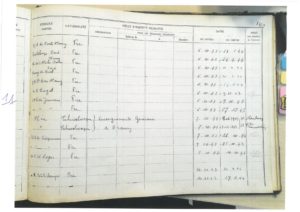

Photographs of Drancy Camp, Shoah Memorial archives

Drancy camp was in the suburbs, 4 km from Paris. It was a long, four-story, U-shaped building flanked by five high-rise blocks.

Building work started on the housing estate in 1932, but it was still not completed when war broke out. It was then converted to an internment camp. A double row of barbed wire was added, with a walkway around the camp. The buildings surround a courtyard about 200 yards long and 40 yards wide. Watchtowers were installed on all four corners of the building.

From June-July 1943, an Austrian SS commando unit, headed by Alois Brunner, took over the running of the camp.

Internment at Drancy:

Andrée Warlin, in her book “L’impossible oubli“, describes the moment when the child victims of the roundup of July 21-25, 1944 arrived at Drancy. She tells us that the children came by bus, without their parents. They had not had time to get dressed before leaving, “they were jostled and dragged from their beds”. When they arrived, a woman escorted them, “dragging them after her, pushing them in front of her. They were left in empty stairwells, with improvised diapers”. To sleep, the children were piled in on top of each other, in beds full of bed bugs. The camp was very upset, “in 10 months, this was the first time that unaccompanied children had arrived.”.

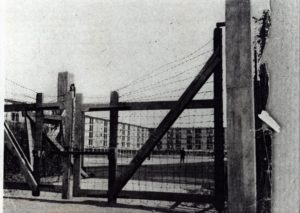

What do we know about the Tasiemka children’s stay in Drancy? To tell the truth, very little. The Drancy transfer registers 37 and 38 give us some basic information.

Cahiers de mutation du camp de Drancy, Archives du Mémorial de la Shoah

Adolphe Tasiemka did not share a room with his sisters. He was assigned to stairwell 6, room 4, while Régine, Marie and Anna were in the same building but in room 2, with Eva Nadel, who appears in the photograph with Anna. They were assigned the numbers 25390, 25391, 25392, 25393 respectively.

July 31, 1944, the departure of Convoy 77

Bobigny station had been the departure point for convoys to Auschwitz-Birkenau since July, 1943

A location plan and postcards of Bobigny train station: Bobigny Municipal Archives

How was the departure organized?

Once again, Andrée Warlin explains: “One day we watched them leave. The Allies had not advanced quickly enough. The miracle had not happened. The courtyard was empty, no more youthful singing and shouting. The courtyard was deserted, no one wanted to go there anymore, everyone stayed in their room. Drancy was crying for its grandchildren. They were gone.”. »

Two other eyewitness accounts, those of Yvette Lévy and Denise Holstein, both survivors of Convoy 77, help us tell the story of the transfer from Drancy to Bobigny.

“At 8 a.m., everyone was gathered in the courtyard of Drancy with their belongings. The buses were waiting for us; there were 50 of us per vehicle. The weather was very nice that day, we were singing on the bus and we had been told that we were going to work in Germany. However, we were suspicious because the children had had to come too.”

“Once we reached Bobigny, boarding was very quick, the little ones were 60 per wagon and we, the older ones, were 100. There was one bucket of water and one bucket for natural needs.”

At noon, the convoy set off: “There were 1,300 of us being taken to the unknown…”. Among them were Adolphe, Anna, Régine and Marie Tasiemka.

-

LE TEMPS DE LA MEMOIRE

Commemorating the Tasiemka family, and also the other people who were deported just because they were born Jewish, on convoy 77, on July 31, 1944 from Drancy to Auschwitz, brings us to the question of how to pass on their memory.

In today’s anti-Semitic atmosphere, the crucial role of the last remaining witnesses cannot be overemphasized. After a first attempt which was not successful due to the Covid19 restrictions, we were fortunate to be able to welcome Mr. Robert Frank to the school on Tuesday, May 25. His testimonial is included in our web documentary.

What will happen when the voices of the last remaining witnesses are gone? What tools can we use to pass on the message?

First of all, there are the memorials and the official sites. Of course, we always think of the municipal, departmental and national archives, the Shoah Memorial, but there are also museums such as the one in Royan, which we were finally able to visit on Thursday, June 10.

We needed to visit the museum to find out more about two of the places that were part of our search for the traces of the Tasiemka family (see our web documentary).

There are also commemorative plaques. During our trip to the Dordogne, we found the plaque placed by Robert Frank in Festalemps, but we found nothing similar in Bourg-du Bost.

Photograph of the commemorative plaque that Robert Frank had put up in the village of Festalemps, taken during our trip to the Dordogne

In Poitiers, not far from the Departmental Archives building, there is a memorial stone that serves as a reminder of the existence of the internment camp on the road to Limoges.

Photograph of the memorial kindly sent by Jean-Philippe Bozier of the Vienne Departmental Archives. It dates from before the stone was updated to include the Spaniards who were also interned in the camp on the Limoges road in Poitiers.

Lastly, in Paris, there are some other memorial plaques that refer to this story.

Photographs of two commemorative plaques referring to the roundups that took place in Paris in July 1944

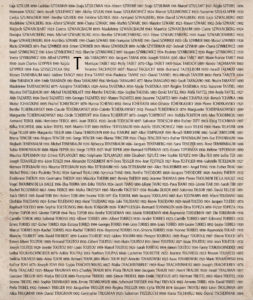

The wall of names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris also includes, among the 76,000 names of deported Jews from France, those of the Tasiemka children.

Photograph of the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

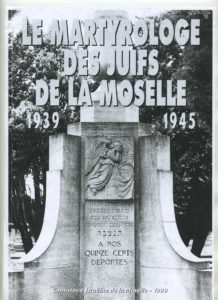

There is also a Martyrology the Jews of the Moselle region, in which we find the names of the 4 Tasiemka children, of which this is an extract, kindly sent to us by mail by Mr. Henry Schumann.

Extract from the Martyrology of the Jews of Moselle

Finally, although we felt sure as we were on our way to Royan that the bombing of January 5, 1945 would have wiped out any trace of Villa Emirazal, where the Tasiemka family stayed during their time in the town, we were in fact able to find the building on the Avenue de Bordeaux.

Photograph taken during our trip to Royan on June 10, 2021

Remembering the Tasiemka family also evokes another highlight of this school year shared by the students: a meeting during which the film “Une vie nous sépare” (A lifetime apart) by Baptiste Antignani, was shown. Through the Escales documentaires de La Rochelle, in partnership with the ONACVG 17, we had the opportunity to discover the work of this young artist who was, until recently, at the Pierre Corneille high school in Rouen. His project naturally aroused our interest since it includes with the meeting between this filmmaker and Denise Holstein, who was deported on Convoy 77. Although 94% of the people on Convoy 77 never came back after having been deported, including Adolphe, Anna, Régine and Marie, this film enabled us to hear from one of the few survivors. After seeing the film, we were able to have a video conference with Myriam Weil, the producer of the film, and the co-director, Raphaëlle Gosse-Gardet.

Photograph of the students involved in the project during the videoconference

Our students were asked about their feelings about the film, and here are some of their responses:

What moved us was “above all, Denise’s testimony, her story, her memories, in particular the time when she saw her parents for the last time, and the moment that they arrived in Auschwitz, when she held the little girl’s hand and then let it go”. There was also the relationship that she managed to build with Baptiste, “a relationship of trust, a relationship that was built through shared moments that we saw in a number of excellent segments, in particular the moment when Baptiste decided to go to see the “ash pond” in Auschwitz and told Denise over the phone about what he had seen. We could sense the emotion that both of them felt. It was a film that really meant something to us. “It talks about Denise’s adolescence. We were able to empathize with her because we are the same age as she was at the time, give or take a couple of years. Through the medium of film, we felt a certain closeness to Denise. The film made us feel we knew her personally. We got to know her better as we went along, at the same time as Baptiste did, which was very interesting. Denise is portrayed as a very strong and endearing woman. Her bond with Baptiste is truly wonderful.” Through the story of Denise Holstein, we drew closer to the story of the Tasiemka children, who also passed through Louveciennes and Drancy camp before they were deported on Convoy 77.

In remembering and writing the biography the Tasiemka family, we have won a bet on young people’s ability to “pass on memory”. Baptiste Antignani is the perfect illustration of this. To complement his film “Une vie nous sépare”, he wrote the following words in the book of the same name:

“Mankind alone has proven, and still proves on a daily basis, that living together [in harmony] seems to be an elusive dream, almost impossible to achieve. The news over recent years bears witness to this. The hatred that some have for Muslims, the desecration of Jewish cemeteries … Speaking of the future is frightening. It is surely too late, and we will have to face this future, but our young people have a duty to continue to fight against obscurantism.”

Lastly, while remembering the Tasiemka family, we welcome initiatives such as the Convoy 77 project, which has helped our students grow by allowing them to approach the history of the Holocaust in a different way, through micro-history and the study of one family’s fate.

We would like to complete this web documentary in two steps:

- First of all, through the words of our students, by asking them what this project has meant to them:

Emma

Last year, I chose to be part of the Convoy 77 project because I wanted to learn more about the Holocaust and the consequences of this tragic event. I wanted to do my duty of remembrance to this family, to retrace their lives so that people know about their tragic fate, and to pay tribute to them. During the year, I was able to learn more about the Shoah and also discover some very moving testimonies, such as those of Denise Holstein and Robert Frank. I am very glad to have been involved in this project.

Youna

I chose last year to participate in the project Convoy 77 for several reasons.

Firstly, I wanted to learn more about this period of history (the Second World War) and the journey of the numerous families who were deported. I found it very interesting to study the history of one particular family and to understand their whole journey, which is similar to that of so many other families.

Secondly, I thought it was important to give a sense of identity to this family, who did not survive and were therefore unable to testify to their story.

Lastly, having us participate in this project keeps the duty of remembrance alive via young people, which I feel is important.

Solal

I wanted to participate in the Convoy 77 project because I feel concerned personally by this subject, given my background, and I believe strongly that everyone should have a duty to remember so that the same atrocities are never repeated.

Over the course of our many discoveries and the testimonials, I was moved by the journey of the family we were studying.

I enjoyed participating in this project because there was a good team atmosphere among us and the work was shared between us.

On another note, I think it’s a shame that not all of the 9th graders got involved in a project like this because it seems to me very worthwhile.

Clémence

The “Convoy 77” project interested me a lot and helped to reinforce the knowledge I had already acquired through courses, books and films. Tracing the history of the Tasiemka family has brought us closer to what these families went through. The project also allowed us to meet witnesses such as Robert Frank, who told us about his very moving childhood.

Alice

The Convoy 77 project taught me about the living conditions of Jewish people, deportation and the concentration camps. I feel it is important to know what happened. It helps us not to forget and to do everything possible so that it never happens again. Last but not least, this project allowed me to meet people such as Robert Frank and to hear a first-hand account of his experiences.

Madeleine

The Convoy 77 project enabled me to learn much more about what happened in the Second World War, and especially about the fate of the Jews during that time. It also gave me the opportunity to honor the Tasiemka family and all the other families who were victims of these atrocities, so that they will not be forgotten.

Paul

First of all, the Convoy 77 project taught me about the life of Jewish children and adults at the time of the deportations, how the Charente Maritime departmental archives are organized and how to search for historical documents. We also had the chance to meet several witnesses of the deportation Jews.

This project showed us how lucky we were not to have experienced the same childhood that some of the deported children had. Many of them were separated from their families at a very young age, so we should be thankful for the childhood we have today.

Kadiatou

The Convoy 77 project taught me a lot about cohesion and teamwork, about searching through archives and about interviews. In addition, meeting the people who were directly involved moved me enormously. Thanks to this project, we were able to pay tribute to all those people who sadly died in the death camps.

Inès

Over the course of the year, this project has taught me so many things. Prior to this, I didn’t know much about this subject or its consequences. Now I feel involved in this cause and I am very glad of that. I am grateful that I was able to learn about this story and about this Tasiemka family in class this year.

Laura

I wanted to participate in the Convoy 77 project so I could contribute to the work of remembrance.

This project helped me to mature and also made me aware of the severity of the Second World War. I also became aware of how cruel people can be to each other.

The interview with Mr. Robert Frank moved me very much because his story is so sad, and I think it is very courageous of him to tell his story to students.

I very much enjoyed participating in this project.

Lucie

The Convoy 77 project has helped me to make better choices for my future studies because, as a history buff, it gave me the opportunity to do some real research about the Tasiemka family. It made me appreciate the hell that my great aunt and my family went through. This experience was also a wonderful opportunity to listen to testimonials, such as that of Robert Frank, and also to go on the trip to Bourg-du-Bost. Finally, I would say that the Convoy 77 project was a very worthwhile experience.

Sidonie

The Convoy 77 project helped me explore the depths of the Holocaust as we followed the story of the Tasiemka family, who lived through it and were destroyed by it.

I am already quite sensitive, but the meetings with the witnesses, and in particular with Robert Frank, had a huge impact on me. This man really moved me and his story deeply affected me.

These testimonials confronted me with the atrocity of mankind and put faces to some of those who endured such pain

Sarah

I learned a lot by participating in the Convoy 77 project. I went to see some archives for the first time in my life, despite the Covid19 restrictions. I also learned about interviewing techniques, using the FAR’s equipment and with Benjamin’s help.

It was very interesting to trace the life of the Tasiemka family, and most of all it was an important task.

The project also brought me something that I hope I will never forget; meeting Robert Frank. His testimony was more than impressive, and I am very grateful to him for sharing it.

Jeanne

Doing the Convoy 77 project was above all a way for me to begin studying the Second World War “early”, along with learning about the genocide of the Jews and gypsies, topics that I, like many others, had been looking forward to since the 6th grade.

Prior to this, the Holocaust was an abstract, vague concept for me. I couldn’t imagine the extent of the harm, the excesses of certain human beings, and reading comic books about it was not going to help me understand. Today everything is different. My involvement in the project taught me many things, but I quickly understood that the fate worse than death for these innocent families was being totally forgotten.

Being forgotten, fading into oblivion, was the enemy of our investigation. Have we succeeded in fighting against it? Perhaps… But most of the witnesses are no longer with us to confirm this.

This memory work taught me a lot, but I was able, for a few months, to put myself in the shoes of these children, children like us, except that they had never asked for anything. Compared to the drab image I had of children who had lived before me, I understood that we were in no way different, and it is this feeling of omnipresent empathy that led me to feel so much emotion during the project, especially during Robert Frank’s testimony. His story would have been similar to that of the Tasiemka children, had they escaped the Nazis’ fury.

I really enjoyed digging deeper, finding all the little details: the camembert cheese that was handed out as they boarded the train from Metz, the concentration of hidden children in the Dordogne… these are certainly not things that I would have learned in a normal class.

To conclude, Convoy 77 is a project in which I do not regret participating in any way. It opened my eyes to realities that were not my own, enabled me to meet a witness who gave us one of his last testimonies, and made me think a lot about how lucky we are today, to live in a free democracy, and in peace.

- Secondly, in conclusion, there are the final scenes filmed by our students during our trip to Royan on Thursday, June 10, with Ms. Binot-Allaire, a member of the Friends of the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation, near the monument to the martyrs of the deportation in the Square of 8 May 1945, in Royan (these can be seen in our web documentary).

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Bonjour .

Bravo pour le dossier.

J’en ai eu connaissance car je suis membre de CONVOI 77 (la femme de mon grand-père , Beila SILBERBERG, a été déportée ) . Les petits enfants de Beila vivent au Portugal.

Il se trouve que mes parents ont vécu la guerre en URSS , et que ma mère est native de KOCK, comme Abraham Tasiemka. Né en URSS en 1945, j’ai vécu 12 ans en Pologne de 46 à 57. Je parle donc Polonais.

En 2016 j’ai pu visiter KOCK , où nous avons été reçus royalement. Je tiens à votre disposition le “livre de mémoire de KOCK”, décrivant l’histoire du village et de sa population avant guerre .

Bonne continuation.

IS