Léa WARECH

Last September (2020), 29 students from the Aristide Briand in high school in Saint-Nazaire, in the Loire-Atlantique department of France, started their Convoy 77 project to write the biography of one of the deportees: Léa Warech. The task was offered to this particular class since it focuses on the humanities.

Falling within the scope of moral and civic education classes, as well as relating to the history curriculum in the final year of high school, this project reflects the students’ commitment to citizenship and remembrance.

From the outset, we were pleased to be able to contribute to the project, motivated by the desire to keep alive the memory of the unique yet multifaceted life of someone who gave her all, and risked losing everything, in order to defend the values that she held dear. After being arrested as a member of the Resistance, Léa Warech was ultimately deported because she was a Jew.

It seemed important to us to bring Léa Warech back to life through writing her biography in a clear and concise manner, to ensure that her memory lives on.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

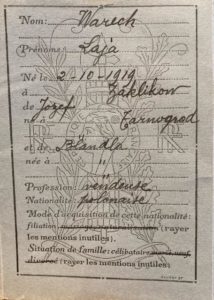

Léa Warech was born in Zaklików on Thursday, 2 October 1919. She was the daughter of Joseph Warech and Brandla Morenfeld, both of whom came from Poland. She lived there until she was 6 years old, when the family left for France. Her new life began in Denain, a town in the north of France, but it took a new turn when the war broke out in 1939. She then had to make life choices and decisions that would shape her future.

The family’s arrival in France

Zaklików, Thursday October 2, 1919: Léa (Laja) Warech was born in a small town in eastern Poland (50 miles south of Lublin). Her parents, Joseph, 28, and Brandla, 20, who were Polish Jews, were married in a religious and civil ceremony on December 13, 1907 in the same town. It is worth mentioning that the population of Zaklikow was predominantly Jewish and based on life in a Shtetl (a Jewish village community).

Joseph Warech, Lea’s father, was born on July 15, 1879 in Tarnogród. He was the son of Israël Daniel Warech, who was born in Zaklików in 1846 and died in 1914, and of Marjem Maria Winer, who was born in Krasnik and died on August 23, 1928. Joseph Warech, Lea’s father, was born on July 15, 1879 in Tarnogród. He was the son of Israël Daniel Warech, who was born in Zaklików in 1846 and died in 1914, and of Marjem Maria Winer, who was born in Krasnik and died on August 23, 1928. They were a lower middle-class Polish family. Joseph, with his self-effacing and quiet nature, was the patriarch, and it was he who made the decisions and always had the last word.As for her mother, Brandla Warech, née Morenfeld, born on October 13, 1887, in Zaklików, she also came from a Polish family made up of her father, Icek Morenfeld, born in Modliborzyce in 1837 and died in 1900, and her mother Marjem Maria Erlichzonow, born in Krasnik in 1848 and died in 1885. She had more personality, was more authoritative and more resourceful.

Lea’s parents had never felt either Russian or Polish but very much Jewish. Due to their religion, they had been persecuted and subjected to violence by both Russians and Poles. In fact, the area from which they came had been disputed by Russia and Poland throughout the first part of the 20th century.

Lea’s father, Joseph, lived in Lodz from 1910 to 1914. He took part in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, then was drafted into the Russian army during the First World War, during which he was unfortunately captured by the Germans. He was released in 1918, a year before Léa was born. When he returned from the war in 1918, he was reunited with his wife Brandla and their first three children. During the time that he was held prisoner, they had gone back to Zaklików, where her family helped to support them. On his return, Joseph continued to work as a weaver.

Joseph and Brandla had five children. The eldest, Sura (Drejzel), was born on July 24, 1910 in Lodz, and their son, James (Ichok), was born on July 30, 1912 in Lodz. Malka was born on January 20, 1914, also in Lodz, Léa (Laja) was born in Zaklików on October 2, 1919, and the youngest of the family, Elka (Olga), was born on February 25, 1922 in Zaklików.

![de gauche à droite les 5 enfants : Léa, Sura, Jacques, Malka et Elka WARECH [collection particulière famille Warech]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WARECHEnfantsLaCoupole-1024x655.jpg)

From left to right, the five siblings: Léa, Sura, Jacques, Malka and Elka Warech. Date unknown, [from the Warech family’s private collection]

Valenciennes Synagogue [private collection]

The family felt at home in France: they all considered themselves “French Jews”. They went to the synagogue in Valenciennes and got together for religious and family holidays. Brandla was the one who kept up the Jewish traditions in the family, by observing dietary rituals (for example, she killed and bled the chicken for the meal) and by speaking the language (they spoke Yiddish at home and used it to write to Joseph’s sisters in the United States).

The whole family tried to obtain French citizenship through naturalization. Their applications were refused except for that of Isaac, who was going to do his military service.

When Joseph’s application for naturalization was refused, it was noted that he worked as a travelling salesman, a trade in which the “interest was very mediocre”. It was on this basis that his application was adjourned.

The two youngest children, Léa and Elka, went to nursery and elementary schools in Denain.

![Certificat de scolarité Léa Warech [Archives nationales 19770884/169 dossier n°33619X34]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/24WARECHJosephANNAT19770884-169-33619X34-1024x627.jpg)

Léa Warech’s Elementary School Certificate [French National Archives 19770884/169 dossier n°33619X34]

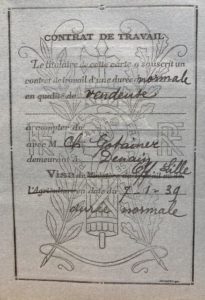

Léa studied hard and passed her Primary School Certificate and then her Commercial Certificate at the Ecole Pratique de Commerce et d’Industrie (Practical School of Commerce and Industry) in Denain. She was a good student, very sporty and energetic. She then passed diplomas in both accounting and dressmaking, after which she worked for her brother-in-law, Charles Gotainer, as a shoe saleswoman. Soon afterwards, she got her driving license.

Léa Warech’s identity card, ref. ADML 120W65

In May 1940, when the German troops arrived, the exodus began. The family left by car for the Maine-et-Loire department of France. Léa testified: “I remember seeing my father cry only once and it was when the Second World War broke out. Misfortune was about to descend on our family”. [USC Shoah Foundation, Los Angeles]

![De gauche à droite : Malka, Brandla, Elka et Léa WARECH Vihiers [DAVCC 21 P 549271]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WARECHBrandla1940-19421-1024x669.jpg)

From left to right: Malka, Brandla, Elka and Léa Warech in Vihiers (between 1940 and 1942) [DAVCC 21 P 549271]

From June 1942, they had to wear the yellow star. In mid-July 1942, the family received a card from Pithiviers. It was sent by Abel Simenov, to notify them that he had been arrested. The family thought that only the men would be arrested. Charles Gotainer was about to leave for Laval to meet up with a fellow Freemason, Mr. Dussart. While he was waiting for the bus, the Germans arrived, together with some French people, to hunt for the family.

The Germans came to the four houses in which the extended family was living in order to arrest them. Léa, who was at her sister’s house, saw them coming and jumped out the window to warn the others by sending a message via a neighbor.

On the evening of July 15, 1942, eight members of the family were arrested. They were taken to the Grand Séminaire (seminary) in Angers. This is where all the Jews who were rounded up in the Vendée, Loire-Inférieure and Maine-et-Loire departments were grouped together after the roundups of July 1942. From there, Convoy No. 8, the only transport to leave directly from the provinces, departed for Auschwitz, with eight members of the family on board. Only Léa’s mother and her four grandchildren remained in Vihiers.

These arrests upset the residents of the village and the curate, a man called Delépine, condemned the arrests publicly during Sunday mass.

Léa, who had run away at the time of the arrest, hid at Mrs. Cassin’s house. However, she could not stay there for fear of endangering her hostess. She was afraid that the mailman or the neighbors would turn her in. She therefore decided to leave for Paris, with the help of Mr. Monéger, where she would be known as Suzanne Roche. Her mother went with her to the station. It was the last time they would see each other. They hardly spoke, each of them preferring to gaze at the other and engrave her face in her memory.

When Léa arrived in Paris, it was the accountant at the Blanc company, a Mr. Victor Coret, who worked with Mr. Monéger, who hired her as an office employee. She worked at 96, avenue de la République, in the 10th district of Paris. Her employer knew that she was Jewish.

She lived with a Mrs. Arthuis, who sublet an apartment at 64, Avenue de la République to Léa and a woman called Denise Klotz. Mrs. Arthuis was not aware of Léa’s circumstances and thought of her as just another tenant. With her false name, the resistance fighter did not wear her yellow star.

Becoming involved in the Resistance

Lea’s resistance efforts begin with a desire to help her community. She always carried forged papers or cards to help young people or families who wanted to escape the searches of the occupying forces.

She helped many Jewish families by offering them various documents free of charge, such as false identity cards or food tickets, as Dr. Burstein confirms in his testimony.

Mrs. Zeikinski, a widow who had been deported, testified on November 22, 1958 that Léa had given her and her family identity cards in November 1943.

![Témoignage de Me Zeikinski [extrait des archives de la DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/TémoignageZEIKINSKI.png)

“[…] clandestine activity, because she warned us when there were roundups or other happenings, she seemed aware of the events that might take place. While she was with us, I told her that being JEWISH, my parents who were in Paris were wanted, my father having once been arrested and detained in Drancy, from where he had been sent back a few months later. This Miss ROCHE, Suzanne, referred me to a nurse […].”

But how could Léa have obtained such documents? She said she kept in touch with people at the Vihiers town hall who supplied her with false identity cards. She also looked for apartments to house Jews who were living in hiding.

She also found ways to get people who wanted to flee across the demarcation line (the boundary between the German-occupied zone and the free, unoccupied zone). Mrs. Arthuis confirms this in her testimony. In addition, Léa warned the Jews when a roundup (a police operation aimed at mass arrest of a certain sector of the population) was about to take place.

Léa sometimes requested asylum for people, as she did for the Blondel family for example. She found a safe place for them in Vihiers and provided them with everything they needed, according to her testimony. Léa Warech even hosted Jews in secret in her home, according to Dr. Burstein. This is what happened with a mother and her children who she bumped into outside her building when they were blocked out of their apartment. She took them in for 3 months. She also took on the task of collecting furs, other items, clothing and food from apartments and giving them to Jews in need.

On many occasions, she avoided being arrested by acting with such aplomb that she was never suspected.

She said that she was never afraid. She was young and did what she had to do to help her community. She lived with fake IDs for the duration of the war.

She was in contact with Miss La Rose, who worked at the 15-20, (a hospital in the 12th district of Paris), who used to help her. Might Léa therefore have been part of an organized network? There are no records to confirm this.

Léa also saved her nephew and nieces. But these children meant much more to her, and meant that her family life would converge with her life as a resistance fighter.

In October 1942, Léa’s mother, her nephew, Henri, and her three nieces, Monique, Danielle and Sarah, were arrested and transferred to the Grand Séminaire in Angers and then to Drancy. Léa received a letter from her mother telling her to save the children. She did everything in her power to do so.

Drancy camp registration cards [French National Archives, F9/5736,5744, 5757, 5748]

While in Drancy, Henri caught diphtheria, a very contagious infectious disease, and was transferred to the Claude Bernard Hospital. All the children who had been in contact with him were evacuated from Drancy. Monique and Danielle were transferred to the Lamarck center, then to the Guy Pantin center, two children’s homes run by the U.G.I.F (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) (1). Sarah was sent to the Montgeron center. Léa was able to visit the four children by pretending to be an “Aryan friend” of their family. The children called her “mademoiselle” and no one ever discovered the truth.

During her visits she advised her eleven-year-old nephew to run away at the first opportunity, which he did, and she then took him in. It was more difficult to free her nieces, however. By the use of force and death threats, Léa persuaded a supervisor by the name of Léa Meslay to let her use her visitation rights to impersonate her. She then went to see Monique and Danielle, asked permission from the management to take them out for a walk, and took advantage of the opportunity to help the two young girls escape from the center. To save Sarah, she made a deal with a Jewish couple named Blondel, who were the guardians of the center. In exchange for Sarah, she hid their children, Marcelle and Germaine, in Denain. She then found a safe house for the couple in Vihiers, where their daughters joined them a few months later. Every time Léa retrieved a child, her uncle Simon took them to Denain, where all four of them were kept hidden until the end of the war. Henri, for example, was taken in by his nanny, Ms. Elise.

- The Union générale des Israélites de France (U.G.I.F.) was an organization that was established under a French law passed by the Vichy government on November 29, 1941, in response to a request made by the Germans during the Occupation of France during the Second World War. The U.G.I.F.’s mission was to represent the Jews in dealings with the public authorities, particularly in matters of assistance, welfare and social rehabilitation. These children’s homes, known as centers, were managed by Jews from the Union Générale des Israélites de France. They were responsible for looking after children who were “blocked”, i.e., destined for deportation and not allowed to be released.

Léa’s arrest and deportation

According to the entry register of the Paris sub-prefecture, Léa Warech was arrested on Tuesday, July 11, 1944 at her workplace at 96, Avenue de la République in the 11th district of Paris.

Fortunately, we had access to the witness statements of Mrs. Cécile Arthuis, the woman who rented a room to Léa, of Dr. Mejer Burstein, who testified to acts of resistance on several occasions and of Rebecca Zeikinski, one of Léa’s Jewish colleagues. These testimonies enabled us to better understand how Léa’s arrest took place.

![Maquette Avenue de la République Paris 11ème arrondissement [Clémentine BOUILLAND et Elise DAVID]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/02Maquette-1024x583.jpg)

A layout model of Avenue de la République in the 11th district of Paris [Clémentine Bouilland and Elise David]

On Tuesday, July 11, 1944, the day Léa was arrested, two men from the German and French authorities raided Lea’s apartment. While searching for Denise Klotz, they came across forged documents (identity cards, passports and bread coupons) that belonged to Léa.

When they did not find her in the apartment, the two men went to her workplace, at 96, Avenue de la République, where one of them questioned her in a Mr. Coret’s office. They then found two identity cards and an address book on her. They asked her what the documents were for. She told them that it was so that she would not be sent to Germany. She then tried to escape by pretending to need to use the bathroom, at which point they stopped her and arrested her immediately. The reason she tried to escape was that another employee had left a coat with her star on it on the coat rack. Léa did not want the men who came to arrest her to spot it, so created a diversion by attempting to get away.

![Dossier de déportée résiatnte de Léa Warech description de l’arrestation [extrait des archives de la DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/37WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-774x1024.jpg)

Description of Léa Warech’s arrest, from her application for the title of political deportee [extract from the DAVCC archives, 21 P 617493]

The three women arrived there at 11:50 p.m., according to the entry register of the Paris Police Prefecture. Many Jews were arrested that night. Léa was interrogated and beaten, and when she was accused of being a Resistance fighter, she declared herself to be Jewish. Denise Klotz and Léa Warech were arrested during a round-up by the German security police. Cécile was freed after a few hours, while the other two women were taken to the Hôtel de Ville depot where they spent the night with the prostitutes.

The following day, around 3:00 p.m., they were transferred, probably by bus, to the Drancy camp along with a number of other Jews. Classified as category B, i.e. for immediate deportation, Léa was given the number 25084.

Lea found herself in a camp without any familial or geographical points of reference. She was alone, completely lost in the middle of nowhere. It was July 12, 1944. There she stayed for about a fortnight, in torrid heat, not to mention the sanitary facilities, which were appalling. There was no running water and no toilets; the dormitories were overrun with bedbugs and the mattresses were disgusting. French Jews were separated from foreign Jews. Life in the camp was organized by Jewish leaders. Léa lived with the children and took care of them as she had done when she was a camp counselor before the war. She was outraged by the relationships that some of the adults had with the young girls and she told them so.

The days went by and then one morning some soldiers asked them to leave and to get on a bus from Drancy to someplace else.

“Death or freedom awaited us” [witness statement for the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles.]

Léa was deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp on July 31, 1944 on Convoy n°77.

At Bobigny railroad station, they were all lost, but there was no time to think about it. The soldiers hurriedly herded them into the cattle cars before they had time to protest. They were all crammed in together. The soldiers filled the wagons to the limit, with men, women and children. There were about 60 people per car. Looking around, Léa saw children panicking and distraught mothers, but she felt nothing but emptiness. The train pulled away. They did not know where they’re going or for how long, but they knew they were all packed together with only one bucket of drinking water and one bucket as a toilet. By way of a window, there was only one small pane that could not be opened, but which at least let in a little light. Léa wondered how they would cope with these terrible conditions, which proved to be a valid concern because the more time passed, the more the children cried with frustration and exhaustion. Some adults were sick or dying. As the journey went on, the bucket filled up with excrement, overflowed and eventually tipped over when the train braked. From that moment on, they could no longer sit still; it was almost impossible to endure such a long journey in those conditions. Every ten minutes or so they stood up and sat down again.

During the night of August 2 to 3, the train stopped. They had arrived at last. The convoy went through the gates of death and directly into the Birkenau camp.

Before they even got out of the train, they could hear dogs barking and angry German soldiers shouting. When the doors opened, searchlights were shining on them and the screams grew louder and louder. Léa says she understood what was happening right away. When they finally got out, a smell of burning flesh caught their throats. A truck was parked on the left and in the center stood a German officer with a stick. It was Dr. Joseph Mengele. It was he who made the selection. They were separated into groups, the men on one side, the women and children on the other, all going where they were told without arguing, for fear of retaliation. Léa was wearing a red armband, which identified her as a health worker. She had got it from a dentist in Drancy called Mr. Filderman. When he gave it to her, he told her that it would save her life since a selection would take place in Pitchipoï (a Yiddish term meaning “a small imaginary world”, which was used in Drancy to describe the destination of the people who were leaving).

“I had been lucky enough to get a red armband that I put on my arm, […] I was sent towards the women who were going into the camp.” [witness statement for the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles]

Only two people from her cattle car were saved; Léa and a doctor from Lyon.

Auschwitz Birkenau was a huge, specialized camp, comprising many distinct sections. The men were taken to one area of the camp while the women went to another. All were put in quarantine to determine if they were carrying any diseases. Léa and the other women entered a large room known as the sauna; unaware of what was going to happen to them, they just followed the orders. What came next was undoubtedly the most difficult ordeal of all their lives so far. They had to undress in front of all those unknown people, a sense of shame coursing through their bodies. Lea was very shy, as were the other women who were not used to this kind of situation because in those days, nudity was taboo. But at that moment, nobody dared to refuse. They had to listen and follow the orders given. Lea and all the other women stood terrified and naked in front of men who came in and out of the room. It was one of the most dehumanizing things they had ever experienced. After that, they had to take a shower, probably to prevent disease and to get all the dirt off them after the journey, but they had no towels, they had nothing; they just stood there all wet, waiting to be told what to do next.

Then the hairdressers came and shaved their heads, and then shaved their private parts! Again, this was dehumanizing for them… Next, they were led to a pile of clothes, from which Léa took a ragged old long dress. Their own clothes had been confiscated as a token of abandonment and isolation, leaving them with nothing to associate with their former lives. That was exactly what the soldiers wanted, to make them feel alone and vulnerable. Lea and the other women were then taken to their barracks in the “Zigeunerlager” (the gypsies’ section of the camp), which was next to the ramp where the trains arrived and near the crematoria. She therefore smelled the burning flesh all the time and saw the deportees being taken to the gas chamber each time another convoy arrived.

In Lea’s block, there were bunks on three levels. There were several women per bed, with misshapen straw “mattresses”, wrapped in old fabric and full of holes. They soon learned that if one of the women with whom they shared a bed turned over in her sleep, everyone else had to turn over as well because they were so closely jammed together.

The following morning, they met the deportees who were going to tattoo them in alphabetical order. From then on, each woman became a mere number. Léa was very lucky because she happened to have a young Hungarian tattooist who was very kind and gave her a really small tattoo, so that it would not be too obvious. She told Léa and some of the other women from the convoy that they were among the last to arrive and that they might have a chance to get out of there alive, so the tattoo did not need to be too visible. Lea was tattooed on her arm and from then on became number A16 829. Léa, who spoke Yiddish, soon learned how the camp operated from the other deportees she met.The gas chambers, the crematoria, nothing was hidden from her and she believed it all. She had worked it out already, so was not surprised.

The days spent in Birkenau were very all pretty much the same. First of all, there was the roll call, every day, twice a day for at least three hours, and sometimes it went on for a whole day.

The women were in quarantine and thus were not able to work. Their only goal was to survive, in spite of all the abuse they had to endure. Their days were uninteresting and repetitive.

Every day, after roll call, the women had to sit on the floor for hours.

Then, suddenly, they would hear the sound of a whistle, which meant they had to jump up and run to fetch large bricks. Once the women had retrieved their bricks, they had to run for miles with them, and were not allowed to stop.

Then, after a certain amount of time, they were made to put the bricks down before being ordered almost immediately to pick them up again and take them back to the place where they came from. This task was intended to determine who was able to survive and who was not.

However, the one thing that these women endured, which most of them feel was the worst part of their experience, was the selection. When the whistle blew in the barracks, they all had to undress and parade naked in front of people who decided whether they had the right to live or not. None of the women who were selected were ever seen again, they simply disappeared without any explanation. That was why everyone was afraid of the selection, because there was no logical reason to explain who would be deemed worthy of survival.

The purpose of these selections was to get rid of those who appeared less able than the others by sending them to the gas chamber, but also, above all, to immerse the women in a perpetual cycle of terror.

Merely surviving in Birkenau was very tough for Lea and the other women in the camp.

They had next to nothing to eat and were in relatively good shape, depending on the individual. Each of them tried to hold on and survive in their own way, by stealing food, thinking about their previous life or simply keeping hope alive as best they could. And as Régine Jacubert, a survivor of convoy 77, said in her interview: “In order to survive it was necessary to be one of a pair. One strong and one weak. Two weak people did not live together. The strong one needed the weak one to survive because she needed an incentive, a purpose, and the weak one needed the strong one to survive, to have someone to protect her.” [Régine Jacubert’s testimony on the website entretien.ina.fr]

Thus, the women learned to survive as best they could, helping each other and fighting for their survival.

In September 1944, Léa and other women fasted to mark the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur. This was an act of resistance against the system that was trying to suppress them. The kapos (prisoners used as guards by the Nazis) punished them by denying them food for two days.

Léa also says that while in Auschwitz, she lost her religion. “Si Auschwitz a existé, Dieu, on le cherche.” “If Auschwitz existed, God, we are still searching for him.” (translator’s note – as in, an omnipotent God would not have allowed Auschwitz to have been built, or allowed the horrors that took place there). She stated this in her testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles.

This quarantine lasted almost three months, until October 28, 1944. It was three months of suffering and both mental and physical torture for all these women. Three months during which they never saw the entrance or the exit of the camp, as if they were trapped in an endless labyrinth.

On October 28, 1944, they underwent another selection to determine who would be fit to work and who would not. Lea and other women who were deemed fit to work were sent to a different camp, a sub-camp of Gross Rosen, which was 60 miles from Prague.

The journey to this new camp was even more arduous, as this time the deportees were 60 rather than 100 per cattle car. Many people died during the journey. When they arrived at the camp, Lea and the other women were taken by truck to a small place called Weißkirchen, a few miles from Kratzau.

When they got there, they were assigned to a house-like barracks opposite the kitchens. They slept in three-level beds, as they had in Birkenau.

In the morning, the women had so-called coffee, although it was not real coffee, with a piece of bread and in the evening, when they came back, they were given thin, watery soup and one or two boiled potatoes. That is all they had to live on while working twelve-hour days or nights.

Every day, the women were made to line up in rows of five before being sent to work.

They then had to walk three or four miles to Kratzau to work at whatever job had been assigned to them. They were made to do various types of work. Léa was sent to work in an ammunition factory.

The conditions in this camp were quite different from what the women had experienced in Birkenau. They worked hard, had little to eat, disease was rife, and there were enormous lice. Personal hygiene was very basic, if not non-existent, and their living conditions were appalling, almost unbearable. But at least there were no more selections. People died from hunger, cold, disease and working too hard, but no longer due to being selected, which was a great relief for many of them. They were finally free from the fear and anguish of being selected and exterminated for no reason.

In this camp, they all took care of themselves as best they could, as they had in Birkenau, by being positive, by protecting each other or by stealing, for example, because in order to try to survive, they had to be proactive and never allow themselves to be defeated. On May 8, 1945, Léa, then 26 years old, was liberated from the Kratzau factory in the Sudetenland (in what was then Czechoslovakia) by the Russian army. The prison conditions had been so harsh that Léa had to stay there for a month, not well enough to be repatriated. When she was examined on her return to France, she had lost about 33 pounds, had bad teeth and suffered from muscle wastage in her limbs. She must have been in an even worse state at the time the camp was liberated. Due to her poor physical condition, she was sent to spend a month in Monnetier-Mornex in the Haute-Savoie department of France. She stayed in a convalescent home recommended by the Hotel Lutetia, which served as a reception and screening center for deportees, prisoners of war and displaced persons who returned to France after the war. On June 1, 1945, Léa was repatriated by air to Paris. When she recovered, she went to Valenciennes and then travelled by train to Denain, afraid that she would not find any of her family members alive. She eventually found some of them and stayed first with her friend Germaine Regnier and then with her uncle, Simon Varech, who lived at 58, Avenue Jean Jaurès. She also found her 4 nephews and nieces: Henri, Sarah, Monique and Danielle, whom Simon had managed to rescue back in 1943.

She then returned to Paris to stay with a certain Mrs. Kahn, the mother of a prisoner friend of her brother, Jacques. She went back to work for her former employer Mr. Coret, who had been of great help to her during the war.

She also met up again with Serge Gorfinkel, who she had known before the war and with whom she married in the 16th district of Paris on August 20, 1945. Serge Samuel Gorfinkel was an aeronautical engineer. He was born in Kovno or Kaunas, a town in central Lithuania.

Serge was a close friend of the family who had studied in Ghent (Belgium) with Abel Simenov, Danielle and Monique’s father. Serge was also deported to Auschwitz camp on Convoy 70 on March 27, 1944. Léa, now Léa Gorfinkel, was able to become a French citizen by virtue of her marriage to Serge. “I married a deportee because I had 3 children to support […] Only a deportee could do that and no one else. […] I got married so that the children would be all right too. My husband was terrific: he was a deportee, he understood everything, he had to.” From Léa Warech’s testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles. The couple had a lot in common, such as having been deported, being Jewish and having uprooted themselves and moved to France.

The young couple settled in Paris, where Mr. Coret rented them an apartment at 120, rue Nollet in the 17th district.

The family moved back to Denain in early 1948 and opened a knitwear and hosiery store called La Bonneterie Centrale at 186, rue de Villars, which was just a stone’s throw from Jacques’ shoe store, Chaussures Charles. They lived in their former home at 58 avenue Jean Jaurès. Serge then gave up his job to run the store with Léa, him doing the markets and her managing the store.

Serge stopped doing the markets for health reasons in 1966 and the family then moved to Douai, where they lived at 40, rue de Bellain. They then decided to rent another small knitwear store called La Maison du Tricot on rue de Bellain in Douai, but still kept on the Bonneterie Centrale.

![Magasin Chaussures Charles 172 Rue de Villars [collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Magasin-Chaussures-Charles-172-Rue-de-Villars-collection-particulière.jpg)

Jacques’ shoe store, Chaussures Charles, now closed, at 172, rue de Villars in Denain [private collection]

Léa remained very close to her nephew and nieces, now adults. Danielle, for example, got married in 1964 and moved to Denain with her husband, Raymond Mitnik.

Serge died of a heart attack at the age of 65. Béatrice and her husband returned to Douai to help Léa, who was now managing three ready-to-wear stores on her own. Beatrice died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 28, leaving behind three young children, Sacha, Franck and Sabine. They were then raised by Léa and Isy.

Esther worked with Léa in the two stores in Douai until December 1990.

The recognition of Léa’s status as a political deportee and deported resistance fighter

In 1946, Léa applied to the Ministère des Prisonniers, Déportés et Réfugiés (Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees) (which later became the Ministère des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre (Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War)) to request that she be recognized as a political deportee. She had to gather a certain number of documents to prove that she had been arrested, deported and imprisoned. Her request was granted and she received her political deportee card, which was numbered 215900145, in 1952.

![Décision de l’attribution du statut de déporté politique de Léa WARECH [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/13WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-1-789x1024.jpg)

Decision to grant Léa Warech, (by then Léa Golfinkel), the status of political deportee [DAVCC 21 P 617493]

French Republic

Interdepartmental Delegation of Lille

July 4, 1953

DECISION awarding the title of political deportee

The Minister of Veterans and Victims of War has decided to grant the title of political deportee

to Mrs. Gorfinkel Léa,

born on October 2, 1919 in Zaklikow (Poland),

residing in Denain at 186 Rue de Villars

Period of internment taken into account: July 11, 1944 – July 3,1 1944

Period of internment taken into account: August 1, 1944 – May 3, 1945

Card N° 215900145

For the Minister and by delegation

The Interdepartmental Delegate

In 1952, as well as being granted the status of political deportee, Léa applied for the status of deported resistance fighter. Her request was not granted, and it turned out to be a long struggle for her.

What happened was that Léa renewed her request for the status of deported Resistance fighter in 1958, including nine different documents in her application. However, there was a big problem: she did not have a membership certificate to prove that she had belonged to a known Resistance network. This was the main problem each time she applied; she never had enough or any new documents to complete her application. After the war, many people tried to apply for the status of “resistant deportee” since this meant that they could receive an allowance. The ministry therefore strictly monitored such applications and insisted on having evidence that the person had been a member of the Resistance.

Later that year however, in September, the department of deportees and internees asked the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War for more information, taking into account the testimonies of Mrs. Cécile Arthuis, Dr. Burstein and Mrs. Zeikinski.

In fact, Cécile Arthuis, Dr. Burstein and Mrs. Zeikinski affirmed that Léa had carried out acts of resistance and thus proved that she had indeed been a part of the Resistance movement. From these testimonies, we learn that Léa had been involved in a number of resistant activities, including distributing false papers such as identity cards, proof of address, bread tickets, etc. to people in need, and providing shelter in her home for people wanted by the Gestapo.

73 rue de la Roquette

Paris 11

I, the undersigned, Mrs. Zeikinski, widow of a deportee, living at 73, rue de la Roquette in Paris 11th district, certify on my honor that:

Mrs. Léa Gorfinkel, née Warech, born under the name of Suzanne Roche

gave me, in November 1943 – 3 identity cards, for my parents and myself, absolutely free.

I also confirm that Mrs. Gorfinkel rendered numerous services, always free of charge, and in particular she provided apartments to people living in hiding, this from 1942 until the date of her arrest on July 17, 1944.

Paris, March 10, 1958

Unfortunately, in the summer of 1962, the Ministry again refused to grant Léa the title of deported Resistance fighter because her activities could not be classified as acts of resistance as provided for in article 2 of the decree of March 25, 1949, saying that she had “only provided assistance to Jews”

On August 7, Léa was thus denied the status of deported Resistance fighter yet again. The Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War refused on the grounds that “it has not been established, based on the evidence in the file, that the deportation was the result of an act classified as resistance to the enemy as defined in the statute concerning deported and interned resistance fighters”. This was very disappointing news for Léa, who had championed the principle of solidarity (having mentioned specifically in her testimony that she had “come to the aid of her community”).

August 7, 1962

Madam,

I have the honor of informing you that your application for the title of deported Resistance fighter could not be approved.

I am sending you herewith the decision taken after the recommendation of the National Commission of Deported Resistance Members.

Please accept, Madam, the expression of my deepest regards,

On behalf of the Minister,

The director of Statutes and Medical Services.

After being confronted with such exacting bureaucracy, Léa was saddened by this refusal for the rest of her life. And all because she had been unable to prove that she belonged to a recognized Resistance group.

The final years of her life

On December 31, 1990, Léa retired, closed her last remaining store at 40, rue de Bellain in Douai and went to live for 6 months in Cannes, in the South of France. Soon afterwards, she moved to 106, avenue de Suffren in Paris, where she died on September 1, 2009.

Marc, her son, applied for Léa to be awarded the Merit Medal, which was granted posthumously. This was the first time that her acts of resistance during the war were officially recognized.

Léa Warech, known to her fellow deportees as “La Grande Suzanne”, or “The Great Suzanne”, was a strong, courageous woman and a good example for all of us to follow. She was a woman of numerous qualities: courage, valor, honesty and integrity.

We would like to thank:

- Marc Gorfinkel

- Danielle Simenow

- Arlette Gotainer

- Ainsi que toute la famille de Léa

- Elissa André

- Olivier Guivarc’h

without whom we would never have been able to complete this project.

We were more than happy to be given this opportunity to convey and recount the story of Lea’s life. This has been a true work of history and remembrance which has involved a complex analysis of the archives. In addition, the contact with the members of Léa’s family enabled us to better understand a number of points.

Lea Warech is an example for all of us, a role model in terms of her dedication to others. She is an inspiration to us in our daily lives. When asked at the end of her testimony what she hoped for the future, Lea replied:

“For there to be no more Auschwitz, for there to be no more evil.”

“A video in French, in mp4 format, about Léa WARECH’s life is available here on the Média de l’Académie de Nantes website“

Class of TG02: Enora AOUSTIN, Loane AVRIL, Marion BINARD, Mélissa BIREMONT, Candice BOISSONNOT, Clémentine BOUILLAND, Matthieu BRISSON, Céline CAN, Nathan CHEMIN, Jeanne CHEVALIER, Elise DAVID, Ilhem DERRECHE, Diarra DIOP, Yann GABARD, Chloé GUINARD, Sarah HAZEM, Agathe JANNIC, Lisa KUNZ, Aline LAFONT, Chloé LAOUAOUDJA, Sofène LAVOQUER, Léna LEDUC, Mylène MARTINEZ, Jade MAUGERE-OLLIVIER, Alyssa MEUNIER-HUVILLIER, Chloé MONNIER, Titouan RIO, Lou-Ann RIVRON, Dylan SOYDEMIR

Elissa ANDRE, history and geography teacher

Olivier GUIVARC’H, teacher and documentary specialist

Ressources:

Service Historique de la Défense, Division des Archives des Victimes des Conflits Contemporains [DAVCC], Caen:

DAVCC Caen, dossiers de Léa WARECH [21 P 617493], Elka WARECH [21 P 549271], Joseph WARECH [21 P 549273], Brandla WARECH [21 P 549270], Fajga WARECH [21 P 549272], Malka WARECH [21 P 539092], Sarah WARECH [21 P 601734], Sura WARECH [21 P 457556], Chaïa GOTAINER [21 P 457555], Henri GOTAINER [21 P 617657], Abel SIMENOW [21 P 539091], Danielle SIMENOW (21 P 599128], Dossier Stalag XIa [21 P 3001]

French National Archives [AN], Pierrefitte-sur-Seine:

French National Archives [AN], Pierrefitte-sur-Seine: Fichier Drancy-Beaune-Pithiviers: Henri GOTAINER F9/5744, Abel SIMENOW F9/5770, Danielle SIMENOW F9/5747, Monique SIMENOW F9/5747, Brandla WARECH F9/5736, Léa WARECH F9/5736, Sarah WARECH F9/5748

French National Archives [AN], Pierrefitte-sur-Seine: Aryanization files of the General Commissariat for Jewish Questions: Abraham GOTAINER AJ38/4838-dossier2419 ; Chaïa GOTAINER AJ38/4870-dossier10666 ; Simon WARECH AJ38/4814-dossier1741, viewed on microfilm.

Archives International Tracing Service, Bad Arolsen

ITS Bad Arolsen: copies of the original lists of people on Convoy 8 on July 20 ,1942 (Angers-Auschwitz) and Convoy 46 on February 9, 1943 [Drancy-Auschwitz]

Nord Departmental Archives [ADN], Lille:

- Annuaires Ravet-Anceau de 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1935, 1939, partie Denain

- Spoliation des commerces ADN 67W45145-2, ADN 67W45148, ADN 67W45146 et ADN 67W45153

- Foreign trader records:

Abram GOTAINER 1035W20, Chaïa GOTAINER 1035W20, Sura GOTAINER 1035W20,

Brandla WARECH 1035W52, Joseph WARECH 1035W20 - Foreigners’ files: Chaïa GOTAINER 321W115396, Brandla WARECH 321W115396, Joseph WARECH 321W115396, Sura WARECH 321W115396

- Education: registers of the certificate of studies and school certificate, from the Inspection Académique du Nord, 1932, 1934, 1939 [ADN 1899W12, ADN 1899W14, ADN 1899W129]

- Civil status records: marriage acts [ADN 3E17452, ADN 3E4475 et ADN 3E17543]

- Military: registration number of Itchok WARECH [ADN 1R4105]

- Naturalization application files: Joseph and Brandla WARECH [ADN 448W139530], Abel SIMENOW [ADN 448W139994], Fajga WARECH [ADN 448W139902]

Maine-et-Loire Departmental Archives [ADML], Angers:

- Foreigners’ files of Brandla WARECH, Elka WARECH, Fajga WARECH, Joseph WARECH, Laja (Léa) WARECH [ADML 120W65]

- Internment of foreign Jews [ADML 97W39]

- Handwritten census register with signature, September/October 1940 [ADML 97W39]

- Handwritten census register, 1940-1942 [ADML 97W39]

- Foreign Jews Check [ADML 37W10]

- “Jew’ stamp on identity cards [ADML 97W39]

- List of Jews property [ADML 37W10]

- Poster “Judische Gesellshaft” 1940 [ADML 97W39]

- Attendance check,1941 [ADML 97W39]

- Census, June 1941 [ADML 97W39]

- Attendance check for Jews 1942-1944 [ADML 7W1]

- Jewish Insignia, June 1942 [ADML 12W41 et 97W39]

- Round-up July 1942 Maine-et-Loire [ADML 97W39]

- Round-up October 1942 Maine-et-Loire [ADML 97W39]

Denain Municipal Archives:

- 1931 and 1936 Denain Census registers

- Report on the looting of Chaïa Gotainer’s business in Denain during the Second World War, 1967

- Memo about the deportees of the municipality, undated [AM Denain 5H66]

Video testimonies:

- Testimony of Léa GORFINKEL-WARECH [USC Shoah Foundation, Los Angeles, Etats-Unis, DVD, Pal, color, 52 minutes] recorded on December 12, 1995 by Sabine MAMOU

- Testimony of Régine JACUBERT recorded on July 18, 2005 via entretiens.ina.fr : https://entretiens.ina.fr/memoires-de-la-shoah/Jacubert/regine-jacubert-nee-rywka-skorka/sommaire

Written testimonies:

- MITNIK Danielle: “J’avais 4 ans en 1942” (I was four years old in 1942)

- Dossier of documents from the Museum of the Resistance in the Occupied Zone DENAIN including:

- VARECH Josiane: “La communauté juive de Denain en 1939” (1995, 3 pages)

- WARECH Josiane-Rachelle: “Denain à l’honneur d’avoir constamment servi de refuge pour beaucoup de juifs” (undated, 11 pages)

- Testimony of Léa WARECH (undated, 14 pages)

- WARECH Irmgard Jeannette, née BRILL – Report on an oral testimony at the Anne Frank School in Gütersloh, Germany) translated from German in September 1955 [1993, 6 pages]

Photographs:

- Auschwitz-Birkenau: personal photographs

- Denain and Vihiers: personal photographs

- Portraits and family photos: Marc GORFINKEL and La Coupole History Center.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

![Arbre généalogique des familles Warech, Simenow et Gotainer [Yann GABARD, Céline CAN]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Arbre2-1024x737.jpeg)

![La place du marché de Zaklików, côté nord-ouest, années 40 [collection I. Dwornikiewicz]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/106-2-La-place-du-marché-de-Zaklików-côté-nord-ouest-années-40-de-la-collection-I.-Dwornikiewicz.jpg)

![Julia et son mari Simon Varech années 40 [Musée de la Coupole]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WARECHSimonBoutiqueLaCoupoleJpg-684x1024.jpg)

![Plan de Denain 1939 [Annuaire Rivet-Anceau Archives Départementales du Nord]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/05AnnuaireNord1939-1024x707.jpg)

![Maison WARECH 58, avenue Jean Jaurès Denain [collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/58-rue-Jean-Jaurès-Denain-768x1024.jpg)

![Recensement de population 1931 [Archives Municipales de Denain]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/02Recensement1931DenainWARECHJosephAMDenain-687x1024.jpg)

![Certificat de scolarité Elka Warech [Archives nationales 19770884/169 dossier n°33619X34]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/23WARECHJosephANNAT19770884-169-33619X34-1024x672.jpg)

![Certificat Etudes PrimairesLéa Warech [Archives nationales 19770884/169 dossier n°33619X34]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/44WARECHJosephANNAT19770884-169-33619X34-1024x788.jpg)

![Liste des juifs étrangers astreints au port de l’étoile [ADML 12W41]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/09InsignesJuifADML12W41-807x1024.jpg)

![Témoignage du Docteur Burstein [extrait des archives de la DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/témoignageBurstein.png)

![Témoignage de Madame Arthuis Cécile extrait des archives de la DAVCC [21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/TemoignageArthuis.jpg)

![De gauche à droite, Danielle, Sarah, Monique et en haut : Henri [Musée de la Coupole]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GOTAINERHenriSimenowDanielleMoniqueWARECHSarahLaCoupoleJPG-1024x956.jpg)

![Témoignage Mme Veuve Arthuis [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/26WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-658x1024.jpg)

![Témoignage Dr Burtsein [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/28WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-673x1024.jpg)

![Témoignage de Mme Zeikinski [extrait des archives de la DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/52WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-815x1024.jpg)

![Dossier de déporté politique de Léa Warech [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/10WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-780x1024.jpg)

![Dossier de déporté politique de Léa Warech [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/03WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-1024x796.jpg)

![Fiche d’enregistrement du camp de Drancy recto [Archives Nationales F9/5736]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/01WARECHLéaANDrancyF9-5736Recto-633x1024.jpg)

![Fiche d’enregistrement du camp de Drancy Verso [Archives Nationales F9/5736]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/02WARECHLéaANDrancyF9-5736Verso-657x1024.jpg)

![Cahier de mutations Entrée/Sortie Drancy [Archives NationalesF9/5778]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/01CahierDrancyJuillet1944-F9-5778-793x1024.jpg)

![Cahier de mutations Entrée/Sortie Drancy [Archives NationalesF9/5778]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/02CahierDrancyJuillet1944-F9-5778-816x1024.jpg)

![Wagon sur la Bahnrampe Auschwitz-Birkenau [collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Wagon-sur-la-Bahnrampe-Auschwitz-Birkenau-collection-particulière.jpg)

![Auschwitz-Birkenau [Collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Auschwitz-Birkenau-Collection-particulière.jpg)

![Entrée Auschwitz-Birkenau [Collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Entrée-Auschwitz-Birkenau-Collection-particulière.jpg)

![Zentralsauna, Auschwitz Birkenau [collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Zentralsauna-Auschwitz-Birkenau-collection-particulière.jpg)

![Intérieur Block/Châlit Auschwitz-Birkenau [Collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Intérieur-Block-Châlit-Auschwitz-Birkenau-Collection-particulière.jpg)

![Photo extraite du témoignage de Léa WARECH-GORFINKEL [USC Shoah Foundation, Los Angeles]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Photo-extraite-du-témoignage-de-Léa-WARECH-GORFINKEL.png)

![Léa WARECH en 1952 [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/22WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-780x1024.jpg)

![Examen médical à sa sortie du camp [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/17WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-1024x671.jpg)

![Hôtel Lutetia [Lutetia.info]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Hôtel-Lutetia-Source-Lutetia.info_.png)

![Hôtel Lutetia [collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Hôtel-Lutetia-collection-particulière-1024x768.png)

![Extrait de l’acte de mariage Léa WARECH Serge GORFINKEL [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/32WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-806x1024.jpg)

![186 Rue de Villars DENAIN [collection particulière]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/186-Rue-de-Villars-DENAIN-collection-particulière.jpg)

![Témoignage de Mme Zeikinski [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/29WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-824x1024.jpg)

![Décision de l’attribution du statut de déporté résiatante de Léa WARECH [DAVCC 21 P 617493]](https://edu.convoi77.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/56WARECHLéaDAVCC21P617493-765x1024.jpg)

Merci à vous tous pour ce magnifique travail et l’hommage incroyable que vous avez accordé à ma grand mère. Je ne mettrai jamais en cause la reconnaissance, l’amour et la fierté que j’ai envers ma grand mère mais qu’un tel hommage et travail lui ait été dédié me touche sincèrement. Alors à tous, je vous remercie. Et merci de permettre à mes enfants de decouvrir qui etait leur arrière grand mamie.

Magnifique travail.

Un détail : Léa a été nommée chevalier de l’ordre national du Mérite, le 14 mai 1998, soit de son vivant.

« Mme Gorfinkel, née Warech (Laja), déportée et ancienne commerçante ; 50 ans d’activités professionnelles et de services militaires. »

Steve GORFINKEL, contactez-nous à C 77… par le biais de ce site, cela nous ferait plaisir !

Bonjour à toutes et tous

Je tiens à vous féliciter et vous remercier pour ces travaux historiques et émouvants dont j’ai été destinataire par Annie Baumard et Jean-Louis Godet de Vihiers avec qui je partage l’attrait pour l’histoire locale.

Mais par ailleurs, M. Pierre Monéger, métier ferblantier, venu de l’Aveyron, cité dans l’article est le père de mon oncle Paul Monéger (époux d’Aline Reveillère, soeur de mon père), les 2 familles Reveillère-Monéger étaient proches depuis plusieurs décennies, habitaient à 20 mètres l’une de l’autre, toutes les 2 artisans, puis unies par le mariage en 1947 de mon oncle et ma tante paternelle. J’ai transmis l’étude à la famille Monéger. Pierre Monéger a aussi été très actif pour cacher des jeunes réquisitionnés pour le STO et des militants communistes de la région parisienne.

Dans l’étude est citée “Ils finissent par s’arrêter à Vihiers et s’installent dans quatre maisons.” : j’aurais été intéressé par des informations, si elles existent, sur ces 4 maisons hors la Maison Monéger car mes grands parents ont hébergé 1 ou des familles au 2 montée St Michel, à 30 mètres de la maison Monéger, rue de l’école (actuellement boulangerie Sellier). Et il y a peut-être un lien.

Un petit détail “Dans ce village il n’y a pas d’Allemand. ” : je laisse bien sur les historiens vérifier ce point; mais, à ma connaissance, des Allemands ont été présents toute la guerre à Vihiers, des officiers et bureaux 40 rue Nationale et en particulier, des soldats allemands dormaient au-dessus de l’atelier de menuiserie de mon grand-père, rue du Minage, à 30 mètres de la maison Monéger, “l’une de 4 maisons”.

Encore une fois un grand bravo aux jeunes et à leurs professeurs.

Loic REVEILLERE – 1 place du Minage VIHIERS