Mathis SZWARC

This biography was written by Joanna Nowicka, a student at the Karol Marcinkowski no. 1 high school in Poznań, Poland.

To come face to face with a person’s past is a unique experience, since it enables us to better understand how an person’s fate depends on external factors, such as the period in history, the social environment, the family, the country, the challenges they faced, etc.

Mathis’ biography, although it includes details specific to him, such as his family background, emigration and arrest followed by his deportation to the Auschwitz camp, from where he never came back, is a testimony to the reality of the Holocaust.

Mathis Szwarc found himself caught between the interests of three countries, Poland, France and Germany, and the turmoil of the Second World War.

Only an open and curious mind can view Mathis’ fate in the context of the situation in the three countries mentioned; only this curious mind can understand what drives present-day societies and ensures the balance between European and world powers. It is this equilibrium that can contribute to preventing a repetition of the Holocaust. Of course, in order to produce a coherent and logical narrative, research into the biography of someone from another country has to be based on translations of all available documents, on the links between events, and on the family members of the person concerned. I (Joanna) could not have done this without the help of Mathis Szwarc’s grandson, Mr. Olivier Schwarz, who provided me with accurate and well-organized information. Nor should we forget the testimony of Olivier’s father, Eloi Szwarc, the youngest of the 4 sons, who was the source of all the information about his life with his parents Mathis and Liba in Livry-Gargan, given in his unpublished interview with Ms. Angles.

In addition, the documents I had at my disposal seemed very meaningful and emotive, especially those concerning his family’s roots.

My work, based on photographs and archived records, as well as on interviews with eyewitnesses, seems subjective. And yet it is built on concrete data: dates, places, relationships or broken links. My contribution to the Convoy 77 project will remain a great honor for me as it allowed me to immerse myself in history autonomously and to develop new linguistic skills.

First of all, I wanted to make sure that the biography would begin with the earliest information available about Mathis Szwarc’s parents. Samuel (Szmul-Zanvel) Szwartz (as spelled on his birth certificate) was the patriarch. He was born in Szydłowiec, Poland, on October 2, 1857, and married Cheiva (Szejwa), born Szwartz in Szydłowiec on June 26, 1861, who was his niece. (This custom, permitted by the Halakha, or “Halokhe” according to the Ashkenazi pronunciation, which was in effect in Poland at the time, encompassed all of the requirements, customs, and traditions that are referred to as the “Jewish Law”. This formed the basis of traditional Jewish religious practice). The family has been settled in Szydłowiec since at least the 1750s

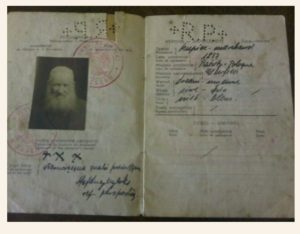

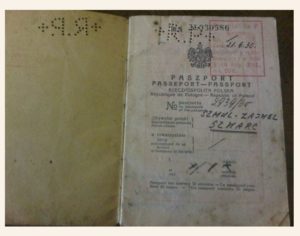

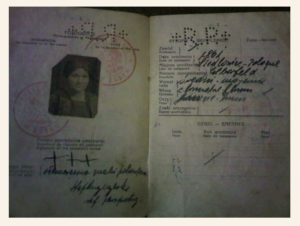

Polish passports of Mathis’ father, Samuel Szmul Szwarc, and his wife, on which they went to Germany in 1923

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

The Szwarc family name was already in existence in Poland in the 15th century, since a Polish coat of arms for the Szwarc family appeared in 1442. This coat of arms was awarded in 1442 by Wladyslaw, King of Poland and Hungary, to Jerzy Szwarc, a town councilor and burgher in Krakow.

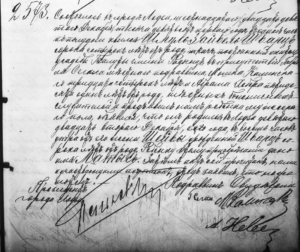

Birth certificate of Matys – Mathis Szwarc – Act no. 2573, dated 1901

Copyright © Olivier Schwarz

This happened in the city of Łódź on December 16 (29)

1901 at 1 p.m. – The Jew Szmul (Shmul) – Zajnvel SZWARTZ,

aged 44, occupation Weaver, permanent resident in the

Bałuty district in Łódź, appeared in the presence of the witnesses

Gabriel SIGAL the Local Rabbi, Moszko KAMINSKI, aged 34, and

Abram HERBER aged 51, hospital employee,

showed us a male child and announced that he was born

in Łódź on December 9 (22) of that year at 8 a.m.

to his legitimate wife Szejwa (Sheva) born

SZWARTZ, aged 40 years. Once the child was circumcised, he

was given the name Matys (Mathis).

We then read this act and had it signed by the

Participants. The Father declared that he was unable to write.

[implying old Russian]

Signature of the Witnesses

Samuel worked as an antique/bric-a-brac dealer in Szydlowiec, together with his wife and family. After they were married, in Szydlowiec on June 5, 1878, Samuel and Cheiva moved to the city of Lodz in around 1880. Samuel became a weaver and acquired a fabric and fine textiles business during the period he lived in Lodz, from 1880 until March 1920. They then lived for a while in the town of Sosnowiec before leaving Poland for good in 1925, when they went to Elberfeld in Germany to join their children and grandchildren. Samuel and Cheiva were the parents of Mathis and the grandparents of Eloi.

Samuel and Cheiva had four children, all born in the Baluty quarter of Łódź.

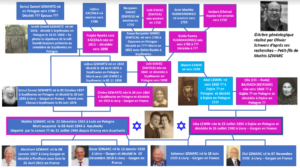

Mathis Szwarc’s family tree

Copyright © Olivier Schwarz

The four brothers in 1935

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

The family at the flea market in 1938

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

The family in 1940

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

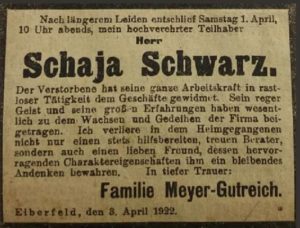

1. Schaya Schwarz born in Lodz on October 29, 1885, went to live before the First World War in Eberfeld/Wuppertal in Germany where he died young in 1922. Schaya was the first of the family to leave Poland for Germany. He worked as a bric-a-brac dealer, selling “junk and rags” and was in the “wholesale trade”. He married Rywka/Régina née Diament in Zwolen, Poland on December 22, 1882. They had three children: Dora, David and Rudolf. After 1922, Rywka/Regina, his widow, stayed in Germany and managed her husband’s business until the 1930s. She then moved to Woluwe Saint Pierre in Belgium, where she lived with her daughter Dora and her husband, Moszek-Chaïm Woydislawski, and her grandson, Harald. Moszek-Chaïm, her son-in-law, was murdered by the Belgian SS on June 21, 1943 at his home, while protesting the arrest of his daughter Dora and his grandson Harald, who were taken to the Mechelen-Dossin camp. On July 31, 1943, they were deported on Convoy 21 to Auschwitz, where they were gassed on arrival. Rywka, having remained hidden in Belgium until the end of the war, was finally able to be reunited with her other two sons, David and Rudy, who had gone to the United States before the outbreak of the Second World War. She died in 1958 in New York. She had lost her daughter Dora, her son-in-law Moszek-Chaïm Woydislawski and her grandson Harald.

Schaya Szwarc, Mathis’ older brother (who died young in 1922) with his wife Regina with their two children David and Dora.

Photo taken in Elberfeld in 1911. Their third child, Rudy, is not in the photo because he was not born until 1921

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

Dora, née Schwarz, Moszek Chaïm Woydislawski and their son Harald. Photo taken in Belgium in 1938

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

Death notice in a German newspaper and tributes to Schaya Szwarc, Mathis’ older brother, dated 1922

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

2. David Israël Schwarz born in Lodz in 1889, moved to Elberfeld/Wuppertal probably before the First World War to join his older brother, Schaya. David Israël married Ita née Lewin, the elder sister of Liba Lewin, Mathis’ wife. Ita was born in Dabie in Poland in 1889. David Israël and Ita had three children Oscar (Michel), Chaja (Hélène) and Adèle. Like his two brothers, Schaya and Mathis, and his father Samuel, David Israël was a second-hand goods dealer.

Photo taken in Elberfeld, Germany in 1927

The three children, Mathis’s nephew and nieces:

From left to right: Adèle, Oscar and Chaja-Hélène

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

3. Mathis Szwarc was born in Lodz on December 22, 1901. In 1926, he married Liba, née Lewin, who was born on July 23, 1891 in Dabie, Poland. Liba was the younger sister of Ita, who was already married to Mathis’ brother, David Israel. Mathis and Liba had four children: Abraham (Albert) born in 1927, Oscar (Roger) born in 1928, Salomon (Simon) born in 1929 and Eloi born in 1930 (see the family tree produced by Olivier Schwarz). The four children were all born in Livry-Gargan, near Paris.

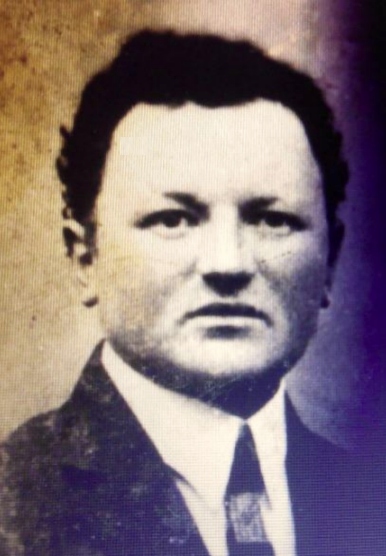

Mathis at the age of 18

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

4. Adèle (Udli) Szwarc born in Lodz on November 16, 1906. She married her cousin, Martin-Motel Schwarz, born on March 19, 1900, on December 25, 1929 in Elberfeld. They also lived in Germany, in Elberfeld. Adèle and Martin-Motel had three children: David, Frida and Harold. As Nazi ideology became more and more alarming for the Jews in Germany, Adele managed to get her three children out of the country in January 1940, got them to the Port of Genoa in Italy somehow, and put them on a boat to the United States. When they arrived, they were adopted by Jewish families in Detroit. Adele then returned to her husband in Germany. As Jews, they were unable to get the necessary permits to leave Germany. Adele and her husband were deported to the Minsk ghetto in Belarus and murdered in the winter of 1941 in the “Holocaust by Bullets” carried out in Eastern Europe.

Photo of Adèle, Martin and their oldest child, David, taken in Elberfeld in 1936

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

As for Mathis, after the First World War, he went to join his two older brothers to help them in their wholesale business in Germany. In March 1920, Samuel and Cheiva left behind their home and Samuel’s store at 43 Kilińskiego Street (formerly Widzewska Street) in Lodz. They went to Sosnowiec, which was still in Poland at the time, and then in around 1922-1923, they moved to Elberfeld, in Germany, to join their three sons and a daughter. Business for the Schwarz family was flourishing, since they were among the “notable Jewish emigrants from the East (Poles)” and Schaya, the eldest, was even President of the Community of Polish Jews in Elberfeld. He, died in Germany in Elberfeld/Wuppertal in 1922. His grave is in the Jewish cemetery in the town (which was not destroyed) still bears his name, Schaya Schwarz, and the dates 1885-1922.

Life in Livry-Gargan before the Second World War (in the years 1923 to 1939)

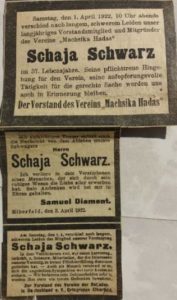

Mathis was sent to France as a scout in 1923. He settled in Livry-Gargan, where there was already a Jewish community and which was served by the tramway to Belleville. He was one of the founding members of a mutual aid organization created between 1923 and 1925 called the “Fraternelle de Livry-Gargan”. This later became the “Fraternité de Livry-Gargan”, and some of the Szwarc family are still active members today, in 2021: Oscar Szwarc was the president of the Fraternity for 12 years and his successor, the current president, is Sandrine Szwarc, granddaughter of Mathis Szwarc and daughter of Eloi Szwarc, who was himself the Fraternity’s standard-bearer for over 20 years. This mutual aid society led to the construction of the Livry-Gargan Synagogue. To begin with, before the war, it managed the membership of La Fraternelle, a Talmudic school, a Yiddish cabaret and the Jewish cemetery of Livry-Gargan. It continued this tradition after the Holocaust: all deceased members are buried in the two Jewish plots in the Livry-Gargan cemeteries, which are owned by the fraternity. Painters from the Paris School such as Soutine, Kikoïne and even Modigliani went to spend some time in the small Jewish community in Livry-Gargan, where life was good and which was really taking off in the 1920s. Mathis bought a piece of land at 147, Chemin des Postes in Livry-Gargan, on which he built his house and a large warehouse. He was a second-hand dealer, scrap metal dealer, and glass and metal wholesaler. David Israël and Adèle were still in Germany in the early 1920s, while Mathis Szwarc’s business soon flourished in Livry-Gargan. He made a name for himself as a businessman, but he was also generous, obliging and always willing to help others.

Mathis’ business card

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

Mathis and Liba standing proudly beside their Citroën B12 convertible, of which they were very proud, in front of their house at 17, (now 147), Chemin des Postes in Livry-Gargan, in 1942

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

Like his younger brother Mathis, Israel David Szwarc was a scrap metal dealer. This is a photo of him on his cart in Livry-Gargan in the ‘30s, looking for scrap metal and shmattès (rags, old clothes)

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

David Israël joined Mathis in Livry-Gargan in the mid-1920s. He worked in the same business, as a wholesaler and scrap metal dealer. The two brothers were neighbors, and lived and worked together. The years 1923-1939 were happy ones. Eloi spoke of “happiness”. The Yiddish cabaret in “La Salle Rappa” on boulevard Chanzy in Livry-Gargan, run by Mathis Szwarc, was a great success. Artists and comedians well-known in the Yiddish-speaking world, such as Dzigan and Schumacher, often came to put on comedy shows, in addition to the musical events. The Epstein couple, comedians and residents of Livry-Gargan, enjoyed asking the audience to throw coins on the stage at the end of the show.

Mathis married Liba in 1926, having brought her to France from Dąbie in Poland. They corresponded in Yiddish for many years before they met in person. Ita, David Israel’s wife, had promised her younger sister Liba that she would marry her brother-in-law Mathis (we have already mentioned that the sisters married the two brothers).

Mathis and Liba Szwarc lived at 147, chemin des Postes in Livry-Gargan in the house Mathis had built before he brought Liba over from Poland.

Samuel and Cheiva, the “heads of the family”, parents of Schaya, David Israel, Mathis and Adèle, joined them in Livry-Gargan in around 1933 when Hitler came to power. They left their daughter Adèle and her family, and Rywka/Regina, their daughter-in-law, behind in Germany.

Photo of Samuel and Cheiva, taken in 1938 at Mathis and Liba’s house in Livry-Gargan, where they all lived together

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

Eloi, at the age of 8, went to Germany for two weeks in August 1938 to visit the German branch of the Schwarz family. He was fascinated by the ” roof-hung ” subway, the Wuppertaler Schwebebahn, which is still in existence in Elberfeld, now Wuppertal. Eloi remembers that during his trip to Germany, his cousin David, a sportsman with the physique of a boxer, the eldest son of Schaya and Rywka, was in prison. He had “trouble at work because he was Jewish and didn’t like to let anti-Semitic remarks be made about him and the Jews”, as Eloi recalls!

Mathis signed his name as Max Schwarz on some official documents. Where did the name Max come from? Eloi does not know!

The second-hand goods business was based in the grounds of the family home. The warehouse was at the bottom of the garden and there were daily drop-offs and sales of all kinds of goods. The grandparents lived with the family. Each morning, Mathis would take the company’s horse-drawn cart out into the streets to clear, collect and buy old clothes, rags and also rabbit skins, since many people kept rabbits for food at that time. Eloi remembers that the rabbit skins had to be dried in the sun before they could be resold or made into clothes (perhaps this was why Eloi and his brother Salomon later went into the fur trade, which was a traditional occupation for Jews throughout Europe). In the afternoons, people came to the house to sell various items. Mathis spoke Yiddish with his parents, Samuel and Cheiva, but he also spoke several other languages: Yiddish, Polish, Russian, German, Yenish (a language spoken by the Yenish, a nomadic people, which uses German grammar and a compound vocabulary that derives its components from German, particularly from dialects of High German, Hebrew, the western variant of Yiddish that had not yet been influenced by the Slavic language, and Romani) and, of course, French, which he mastered perfectly. Liba spoke French too, but with an accent and sometimes it was “Franco-Yiddish”. Eloi remembers Mathis as a kind, not overly strict father. He also recalls playing in the yard with his father and his three brothers at lunchtime or at 4 p.m. when he came home from school. Eloi had “everything he needed”. His father saw to that and wanted his children, his wife and his family to be happy. Mathis loved to sing, especially Yiddish songs and lullabies. He loved classical music, especially the violin, which he wanted his children to learn. He hired a private violin teacher for them. Abraham/Albert had some success but the other brothers had no talent for it. Mathis also had a talking parrot called Coco, and when Liba called her husband “Mathis,” Coco the parrot also kept repeating “Mathis! Mathis!”. The family also owned a dog called Bobby who was always playing with the four sons!

The grandfather, Samuel, who became disabled in his later years, and grandmother Cheiva spoke Yiddish with their friends in Livry-Gargan and at home with the grandchildren. The family was not Orthodox Jewish, although in Poland Samuel had been involved in the Hasidic movement. They observed Shabbat and celebrated Jewish holidays. They ate kosher food if supplies were available (during the Occupation), and they had a chicken coop in the backyard. Next to this was the stable where Mathis kept the horse that pulled his cart. When they were in Poland, Samuel and Cheiva had been more religious, whereas in Elberfeld, Germany, none of the Schwarz family were members of the German Jews’ synagogue. As Polish immigrants, they kept up the Polish Jewish prayer rituals. This is confirmed by the fact that Schaya, Samuel’s eldest son, contributed to the foundation of a synagogue in Elberfeld, together with the Polish Jewish community of which he was president. Despite this, apart from Samuel and Cheiva, Mathis’ family spoke French at home. Mathis read and wrote French with ease, while Liba could read Yiddish and French.

The Schwarz family was surrounded by Italian and Armenian neighbors. They had a spacious courtyard in their home and naturally the neighbors came to visit. On Sundays, the yard (or the field in front of the house) was used as a convivial space for recreation and as a soccer field. There was no friction between the various communities; everyone brought their own culture and shared it with the others.

Livry-Gargan was also a vacation resort for Parisians. It was the countryside, with fields, the Ourcq canal and its boats, the Bondy forest, and the seven islands at nearby Montfermeil. The Schwarz family hosted picnics in the field in front of their house. There was a pilgrimage site, revered by Catholics, with springs said to perform miracles, and the church of Notre-Dame-des-Anges in Clichy-sur-Bois, which was right behind their house. Of course, there was also the Livry-Gargan Synagogue on Avenue Gallieni, where Mathis and his family went on the Shabbat and on religious holidays.

A funfair was held every August in the nearby meadow, which became the most important event of the summer for folk in Livry-Gargan and the surrounding area.

The Schwarz family, like their neighbors, rarely visited Paris. Given that there was such a large Jewish community in Livry-Gargan, they didn’t feel the need to go anywhere else!

Mathis’ sons all used the French version of their first names. The eldest son, Abraham, became Albert and went out to dances. He no longer wanted to be called Abraham, hence the name Albert. Oscar became Roger, and Salomon used the name Simon. The four brothers were always very well dressed, in suits, jackets, shirts, ties and bow ties. Mathis was the same, an elegant man who was always well-groomed. They all felt that it was important to dress correctly. According to the grandparents, the family and Mathis himself, who had all experienced harsh and difficult conditions in Poland, agreed that life in France was much better! After the First World War, the pogroms that took place in Poland prompted many Jews to emigrate to countries such as Germany. Eloi often heard adults talking about this, reminiscing about life in Lodz and then comparing it with Elberfeld and Livry-Gargan.

On Sundays, either at Mathis’ house or at David’s, which was in the street just behind it, the whole family got together. They ate Yiddish food made by Liba or Ita, such as chopped liver, fish balls, matzo (flatbread), the well-known cheese cake called Käsekuchen and apple strudel. They sang Yiddish songs, showed off the clothes that they had made during the week, the Yiddishe Mames exchanged recipes, and the children played marbles and toy soldiers in the yard. The neighbors all had three or four children. They quickly formed a “tribe” and regardless of the guests’ social status, the Schwarz’ door was always open! Mathis took the opportunity to talk shop with the fathers of the other families who, like him, were mostly second-hand dealers and scrap metal dealers.

A Jewish family hunted down

This is how Mathis’ arrest happened: on March 23, 1944: at around 3- 3:30 p.m., the French police were looking for a Resistance fighter and/or a Resistance member who was said to have shot a German officer a few hundred yards away, in Clichy-sous-Bois. The police were therefore looking for these two people and trying to find where they were staying, so were searching several hotels in Livry-Gargan. The manager of a café with hotel rooms above said he did not know them. However, although there is no proof of this, it is said that while he did not report Mathis directly, he deflected, telling the police to inquire at the home of “Schwarz the second-hand dealer”. Mathis was well-known figure all over Livry-Gargan due to his character and his involvement in the “Fraternelle de Livry-Gargan”. Mathis was just leaving his house with his brother-in-law, Léon Zaltz, who was married to Frida, Liba’s second sister after Ita, to get into his sedan. Léon Zaltz and Frida were in hiding in Livry-Gargan and had been staying in the hotel and in various houses, with the help of Mathis. The hotel with the bar below was near Mathis’ house and was owned by an Italian. The French police, together with Bonny and Lafont’s henchmen from the French Gestapo, arrived at Mathis’ house just as he had started his car and was about to go to the butcher’s store with his brother-in-law, Léon, during the hours when Jews were allowed to go shopping. Mathis was wearing his yellow star on his suit jacket. When in his rear-view mirror he saw the police car stop in front of his house at 147, chemin des Postes, he made a U-turn. Mathis stepped out of his car and walked towards the police officers and the two accomplices. They asked him: “Are you Schwarz the junk dealer?” Mathis replied: “Yes, I am”, and the officers grabbed him. Mathis shouted: “Let me go, I’m French!!!” One of the policemen replied: “You are wearing a yellow star, you are a Jew!”, and with that he ripped the yellow star off Mathis’ jacket and arrested him on the spot. At the time, Mathis’ four children were all at school in Raincy. Eloi was 14 years old and had already passed his school certificate. His older brothers were in high school. Liba was at home with her sister Frida (Léon Zaltz’ wife) and a young Jewish girl who was also visiting the house. The police burst into the house. The three women escaped through a back door and despite the gunshots, with bullets flying all around them, the whistling sound of which Liba remembered for the rest of her life, they managed to take refuge in the home of Liba’s sister Ita, who lived in the street behind Mathis and Liba. Mathis was arrested and handcuffed together with Léon Zaltz and a neighbor who was passing by at the time. They were not taken to the Gestapo headquarters on rue Lauriston, but to Fresnes, because they were deemed to be Resistance fighters. “Uncle Zaltz”, who was later deported to Ravensbrück on Convoy 79, was an eyewitness to what happened between March and April in Fresnes prison.

Éloi and his two brothers, who were at school in Raincy, were quickly rescued by their cousin Hélène, a young married woman, the daughter of David Israël and Ita, who took them to hide and take refuge in the house on Allée Bayard in Livry-Gargan that she and her husband had just bought. Then a non-Jewish neighbor of Éloi, Mr. Magne, a locksmith by trade, a war veteran whose son René was friends with the children, and who lived next door, in the allée des Pommiers, took in the four brothers and their mother. They stayed on the ground floor of his bungalow. They all had to sleep in one room, together with another Jewish family which was also in hiding. Mathis Szwarc’s arrest caused a great stir in Livry-Gargan, but sadly this was also true of many Jews in the town, since a hundred or so other members of the Jewish community were also murdered. There is a memorial stone in the old cemetery of Livry-Gargan which bears the names of all the Jewish victims. A few years ago, the Schwarz family wanted to have the distinction of “Righteous Among the Nations” awarded to those who put their lives in danger to save Jews, including the descendants of Mr. Magne. This is the highest civilian distinction awarded by the Hebrew State and by the Yad Vashem Committee in France. However, the Magne family had never wanted it, because they said they had just done their duty as French citizens! These the real righteous people!

Life as a Jewish family in Livry-Gargan, living in hiding without the head of the family, in the spring of 1944

The Schwarz brothers’ businesses were Aryanised. They were assigned a manager. In the garden through which the warehouses were accessed, there was a sign saying ” Aryanised Jewish establishment “. Despite asking for news via their neighbor, the family heard nothing more of Mathis, either in Fresnes or in Drancy after that. In the spring of 1944, the Renault and Billancourt factories were bombed. Some of the shells landed in a quarry just 500 yards from the Schwarz house. The house was hit by stone chips from the explosions. It was impossible for the Schwarz children to go back to school. The brothers went out into Mr. Magne’s yard, but were not allowed to go out into the street. Mr. Magne, who took them in, managed to provide them with food and supplies with the help of his ration coupons. Albert, the eldest, who had started an apprenticeship in Pantin, was let go because he was Jewish.

Any news of Mathis?

Uncle Zaltz came back from the Ravensbrück camp, having been deported on Convoy 79. He was a handsome and quite strong man before he was interned in Ravensbrück, but when he came back he weighed only 78 pounds. He had no news of Mathis. All he knew, like rest of the family, was that Mathis had been sent to Auschwitz. Mathis Szwarc’s first and last names were not on the list of names of death camp survivors at the Hotel Lutetia in Paris. Family members and neighbors searched for him on the list. We looked and looked,” says Eloi, “it was our only hope. Liba, Eloi’s mother and Mathis’ wife, was also hoping: her brother-in-law had come back, so why wouldn’t Mathis?

An eyewitness said that when Mathis arrived at Drancy on 17 July 1944, as prisoner number 25120, he was impotent and in bad shape after his time in Fresnes prison, where he had been martyred and tortured in the basement. He talked about his children and his wife, and shouted in German “I have children. You can’t do this”. He was in a dreadful state when he boarded Convoy 77, the last of the large convoys to Auschwitz, on 31 July 1944. He was murdered on arrival in the death camp on 3 August 1944. At the end of April 1945, the first of the deportees to arrive in Paris were taken to the Hotel Lutetia, which served as a transit and meeting point for those who were lucky enough to return, such as Léon Zaltz. Every day, lists of names were posted, giving details of those who had survived the horror.

“No name, no name, Mathis Szwarc name is not there” on the lists!!! The waiting, day in day out, was unbearable for Liba and her four sons! Uncle Zaltz told Liba and the children, who were asking questions, how the deportees survived, in an attempt to explain a little about life in the death camps. Aunt Frida died of cancer shortly after the war.

Samuel died in 1938 and Cheiva in 1939, just before the Holocaust. “Fortunately” they did not live to see tragedy that struck the Schwarz family as Mathis, their daughter Adèle and her husband, their granddaughter Dora, great-grandson Harald and Dora’s husband Moszek-Chaïm, were all murdered.

In order to survive and still hoping that her husband, Mathis, would come home, Liba bought some goods and copper, without registering a business. In the evenings, when they were staying with Mr. Magne, Liba would go back to her house to look for clothes. After the war, Abraham/Albert became a jeweler’s is apprentice and brought home some of his wages to his mother. The second son Oscar/Roger trained as a locksmith and then took over the second-hand shop in Livry-Gargan, which ran until he retired. Salomon/Simon, the third son, passed his school certificate. He then became an apprentice to a fur trader in rue Miromesnil in Paris, and later became a furrier. Abraham became a jeweler and watchmaker in Pavillons-sous-bois, while Oscar/Roger was a junk dealer at 147, chemin des Postes in Livry-Gargan. As for Éloi, after a spell at an apprenticeship school with a view to becoming an electrician, he soon joined his brother Salomon at the furrier’s in rue Miromesnil in Paris. He then became a furrier-designer for Parisian luxury shops and had a workshop in rue d’Hauteville, in the furrier’s quarter of Paris, before returning to Livry-Gargan in 1976: Livry-Gargan, the family hometown, where nine of his ten grandchildren were born.

Liba kept a vegetable garden, raised and sold chickens and ducks and, together with a Shokhet from Livry-Gargan, performed the Jewish Kashruth slaughter ritual. Éloi remembers that Liba often had nervous episodes following Mathis’ arrest and for some years after the war. Mathis was deported on July 31, 1944 on the last of the large convoys to Auschwitz, Convoy 77. He was murdered on arrival in the death camp on August 3, 1944. It was not until December 19, 1944, three days before Mathis would have turned 43, Liba and her four children received a death certificate telling them that he had died.

Yet, despite the horror, life went on, and these are Mathis and Liba’s descendants as of 2021:

– 4 sons (photo taken in 1948 at Livry-Gargan) the oldest two of whom, Albert and Oscar are no longer alive

Copyright © Fond Liba Szwarc/DR

– 10 grandchildren

– 14 great-grandchildren

– 3 great-great-granddaughters and 1 great-great-grandson.

Life goes on…

What happened next?

Following a discussion about writing Mathis Szwarc’s biography within the framework of Georges Mayer’s “Convoy 77” association, a project designed to improve understanding and make known the fates of the 1,306 men, women and children who, on 31 July 1944, left Drancy for Auschwitz in cattle cars, to pursue the work of the survivors, to take an active part in the transmission of the memory of the Shoah and to bring together likeminded men and women the men and women who feel that the fight against discrimination and hatred includes learning about the processes that led to the Holocaust, Olivier Schwarz, who joined the conversations from his home, was deeply moved by the story and the testimony of his father, Éloi, who until then had kept it to himself. His children, who have been very committed to Holocaust remembrance since childhood, having taken part in many memorial ceremonies, and who are missing a grandfather who died in Auschwitz, wanted to know more about the family’s life.

One day in February 2018, Olivier found two German administrative documents, a commercial license, and a “registration form” dated 1923 in the name of Mathis Schwarz his grandfather. They had been signed and stamped in Elberfeld (now Wuppertal) in Germany. And “It all started from there”. Olivier sent these documents to the local archives service, looking for more information, and as a result discovered that some of his family had stayed in the town, (having fled the pogroms and the city of Lodz in Poland before and after World War I). Elberfeld was a hub of the German Yiddishkeit, where many Polish Jews contributed to the economic boom. His grandfather, Mathis, had a raw materials company at Ludwigstraße 3 in Elberfeld, a wholesale business in rags (Shmattès in Yiddish), bottles and scrap metal. His older brother Schaya Schwarz and their father Samuel (Szmul-Zanvel) Schwarz (his great-grandfather) also owned wholesale businesses in various places in Elberfeld, and lived in the Briller and Luisenviertel neighborhoods.

Then, one day later on in 2018, Olivier received some photos of the tombstone of his great uncle Schaya Schwarz, who died in 1922 in Elberfeld, from the trustees of the “Alte Synagoge” in Elberfeld. He had not known where his uncle died or where he was buried, which turned out to be in the Weinberg Jewish cemetery in Elberfeld. And so, a few weeks after Olivier’s research, we found out that the Schwarz side of the family came from the Shtetl (small Jewish village) of Szydłowiec in the 1750s and then from Lodz around 1880. Their ancestors have been in the flea market, rags, materials (building stone etc.) and stone carving trades since at least the 1750s. Olivier was also able to find Izrael-Dawid Szwartz’ “Matseve Shteyn” or tombstone, dating from 1860. Izrael-Dawid was Samuel’s father and Mathis’ grandfather. His grave, which is still in the Jewish cemetery in Szydłowiec, is one of the few that were not destroyed by the Nazis. He was thus able to put together the family tree, starting in the 1750s with the names and surnames of his great grandparents and including all their descendants, thanks to the Polish, German and Belgian archives. He also found all the American “branches” of the Schwarz family, including more than 40 people that the Schwarz/Szwarc family in France hardly knew existed. Olivier has since started a Facebook group “The Love Schwarz – Szwarc Family”, where he posts all his “discoveries” (new ancestors, documents, civil status records, archives, photographs, anecdotes …) about the Schwarz/Szwarc Family and where the family members can communicate with each other and share their memories!

Photo of the Memorial to the Deportees in the Old Cemetery in Livry-Gargan. Mathis’ first and last names are included in the inscriptions and at the base there is a plaque in memory of him. and at the foot of which is a commemorative plaque / Photo taken in 2019, showing Eloi Szwarc, Mathis’ youngest son, who is the flag bearer of the Fraternity of Livry-Gargan, and his wife, Claudine Szwarc.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Très beau travail de reconstitution, très belle iconographie. C’est passionnant. Merci

Merci Philippe pour votre message …. Cordialement, Olivier Schwarz – Petit – Fils de Mathis Szwarc

Très bel arl’ticle je suis aorigine de mes racines juives dans la région de Lode mon arrière grand mère Théophile Szwarc

Je cherche mais difficile

Courage Krawczyk

J’ai commencé avec 1 seul document et ensuite tout s’est enchaîné pour arriver à écrire l’histoire de notre Famille