Jeannine AKOUN

Photo of Jeannine Ricca AKOUN

©Shoah Memorial, Paris

JEANNINE AKOUN’S JOURNEY

This biography was researched and written by a group of 12th grade students from the Racine high school in the 8th district of Paris, France. The students who began researching Jeannine Akoun’s life story were Corentin Mallié (class TG4), Tessa Milesi (TG5), Ilana Roder (TG7), Lila Senot Verber (TG2) and Poppy Strouk (TG1).

A second group of students then joined the first to retrace what happened to her in Auschwitz: Oscar Barete, Matéo Bastelica, Maya Ben Lahcene, Noah Black, Gislène Boulassel, Félicien Boussard-Wilson, Jeanne Budin, Suzanne Célérier, Valentine Correani, Chloé Mallet, Eden Samak, Jude Thrun and Cléa Valdenaire.

The project was carried out over the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 school years, under the guidance of Nicolas Ivanoff, their history and geography teacher.

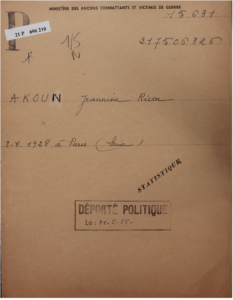

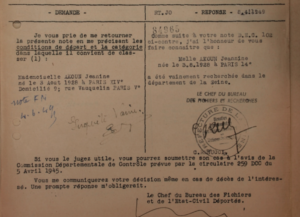

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

Drawing by Noah Black

1. Jeannine Akoun’s childhood and the historical context surrounding it

a) France between the wars: Jeannine Akoun’s birth

Jeannine Ricca Akoun’s birth certificate © Paris archives

Jeannine Ricca Akoun was born at 4 a.m. on August 3, 1928, in the Port-Royal maternity hospital at 123 Boulevard du Port-Royal in the 14th district of Paris. She was born a French citizen because her father, Chemouël Gaston Akoun, who was Jewish and born in Algeria, was eligible for French citizenship according to the “Crémieux decree” of October 24, 1870.

The Government of National Defense,

Decrees:

The indigenous Jews of the departments of Algeria are declared French citizens;

consequently, their current status and personal status shall, as of the promulgation of this decree, be governed by French law, and all rights acquired to date shall remain inviolable.

Any legislative provision, senate consultation, decree, regulation, or order

to the contrary is hereby abolished.

Issued in Tours, October 24, 1870.

Ad. Crémieux, L. Gambetta, Al. Glais-Bizoin, L. Fourichon.

Chemouël Gaston Akoun was born on November 24, 1888, in Algiers, Algeria, and his wife, Reine Esther Laskar, was born on March 24, 1891, in Tunis, Tunisia. We do not know where they met, but they both relocated to Paris.

Chemouël had been married before, but his wife died in 1921.

10 rue des Goncourt in the 15th district of Paris, where the family was living when Jeannine was born.

Jeannine’s birth certificate states that when she was born, the family was living at 10 Rue des Goncourt, in the 10th district of Paris. This was a working-class neighborhood, and the building was nothing special. The walls were plastered, with no decoration, suggesting that the people who lived there were not very well off. Rue des Goncourt is a small, narrow street that runs from Rue du Faubourg du Temple to Rue Darboy. Although it does not get much sun, if the family lived on the street side, the west-facing windows would have allowed some sunlight into the apartment.

Jeannine’s birth certificate also says that her father was “an employee”, although there are no further details, and that her mother made wigs or hairpieces, so presumably worked in a hairdresser’s salon. How happy her parents must have been to bring this little girl into the world.

Jeannine Ricca Akoun’s family tree

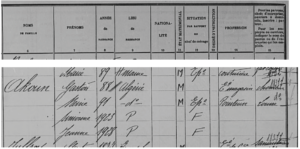

The 1931 census provides us with some additional information. It lists the names of everyone who was living in the building at the time. The Akoun family was still living at 10 rue des Goncourt.

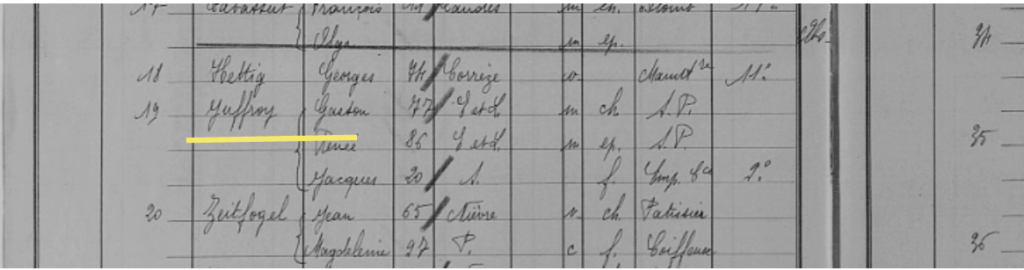

Extracts from the 1931 census, 10, rue des Goncourt

Source: archives.paris.fr

We also found the following details:

- Jeannine’s mother, Reine, was a clock-in clerk at the “Louvre”. We believe this refers to the Grands Magasins du Louvre department store, as the next entry mentions “Samaritaine”, which was another department store. She therefore appears to have changed jobs at some point between 1928 and the birth of her daughter Jeannine. This was a low-skilled job. The census record includes an error, as she is listed as having been born in Algeria, whereas her birth certificate states that she was born in Tunisia.

- Jeannine also had an older sister, Simone, who was born in Paris in 1923. We searched for more information about her, but to no avail. We were unable to find her name in the Shoah Memorial’s list of deportees.

- Jeannine’s father, Chemouël, is listed as a “store employee”, which is a little more specific than the occupation listed on Jeannine’s birth certificate, which simply states ”employee”. However, we also discovered that he was unemployed at the time. In 1931, the French economy was in the midst of a recession and unemployment was rising fast. This may also have been what prompted Reine to change her job.

We continued our research by looking at the next census, from 1936, also in the Paris city archives, in order to track the Akoun family over time.

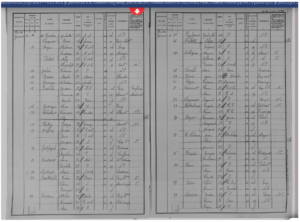

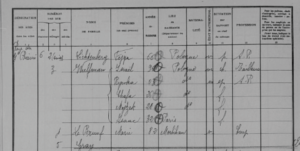

Extract from the 1936 census, 10, rue des Goncourt

This time, however, although we found the names of the Juffroy family (highlighted in yellow in the 1931 register), the Akoun family, who were listed just above them in 1931, was longer living there.

We know that Jeannine’s mother, Reine, had died in the meantime. Without her income, her father may have round it hard to pay the rent, meaning that they had to move elsewhere, but this is merely a supposition on our part.

Extract from the 1936 census, 10, rue des Goncourt

Source: archives-paris.fr

We should also note that a lot of the other residents listed in the 1931 census had moved out by 1936, so the Akouns were not the only people in this situation.

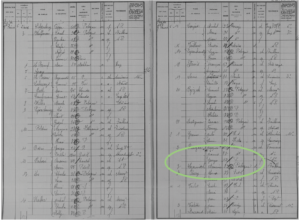

When we examined these 1936 census records in detail, something else caught our eye. Next to the surnames of people thought to be from Jewish backgrounds and of foreign nationality, there are symbols drawn in pencil, as can be seen in the image below. It is unlikely that these crosses date back to 1936, as they were not there in 1931. We therefore believe that they were added at the time of the census of the Jewish population during the war.

This would have been a way of compiling a comprehensive list of family members and their addresses. Some names that appear to be of Eastern European origin (such as the Printzac family, who were originally from Russia and worked in the fur trade, circled in green in the image below) do not have a cross next to them. Might they have moved out between the 1936 census and when the crosses were added? The crosses may also have been added after Jews were required to register themselves at their local police station.

Extract from the 1936 census, 10, rue des Goncourt

Aside from this one case, however, the following two pages show that housing occupancy remained fairly stable between 1936 and the war. There are also crosses beside the names of children who were born in France (Chafa, Mojzek (?) and Isaac Wulfman on the list above), but further research on the Shoah Memorial website revealed that the Wulfman family are not on the list of people who were arrested, deported, and murdered in Auschwitz.

Extract from the 1936 census, 10, rue des Goncourt

Source: archives-paris.fr

Our review of census records for the 11th district of Paris prompted us to take a closer look at the Jewish population overall.

A large number of Jews lived in the 11th district, which had the largest Jewish population in Paris, accounting for around 16% of the total population[1]. Even with the census records from 1931 and 1936, we were unable to determine exact population figures, but based on the data available, we estimate that the total population was around 240,000, including approximately 38,400 Jews. The vast majority of them came from Eastern Europe[2].

Source: lenfantetlashoah.org

In the report documenting Jeannine’s father’s arrest in 1943, the family’s address is listed as 29, rue Deparcieux, in the 14th district of Paris

29, rue Deparcieux, in the 14th district of Paris

We were unable to find out how long the family had been living at this address. We also found no further trace of Jeannine’s sister.

Rue Deparcieux is in the 14th district of Paris, not far from the town hall and to the south of Montparnasse Cemetery. Most of the buildings have plain plaster walls, similar to those on Rue des Goncourt, which again suggests that the residents were quite poor. The building where Jeannine and her father live used to be a hotel. That might explain why it has a brick facade, which stands out a little on this street, this part of which is a is a dead end. However, it could also have been a boarding house for people who could not afford to rent an apartment.

In his book, Dora Bruder, Patric Modiano explains that Dora and her family lived in a hotel similar to the one on Rue Deparcieux. They lived at 41, boulevard d’Ornano in the 18th district:

“From before the war until the early 1950s, 41 Boulevard Ornano was a hotel, as was number 39, which was called the Hôtel du Lion d’Or. […]

I eventually found out that Dora Bruder and her parents were already living in the hotel on boulevard Ornano in 1937 and 1938. They rented a room with a kitchen on the fifth floor[3]

We therefore believe that the Akoun family lived in similar accommodation in the hotel on rue Deparcieux to that of the Bruder family on boulevard Ornano.

We suppose that Jeannine and her father shared a room and that they found it hard to make ends meet.

b) The Jewish population in France prior to World War II

Before World War II, some Jews were well-integrated into French society while others were less so, depending on where they came from and when they arrived in France.

The Akoun family was French, so they lived their lives just like everyone else, notwithstanding some underlying anti-Semitism. They were a typical low-income family who worked in low-paying jobs and struggled during the depression and the financial uncertainty that came with it. Nevertheless, such families were generally well integrated into French society as a result of their involvement in the “economic, cultural, and political life of the country.” Many well-known French personalities, such as André Bergson, Sarah Bernhardt and André Citroën were members of the Jewish community.

Jews from other countries arrived in waves, starting in the 19th century. This was followed in the 20th century (both before and after the First World War) by a larger influx of Jews from Eastern Europe.

These people moved to France for financial or political reasons and for the freedom to practice their religion. There is even a French saying, “As happy as a Jew in France”. The country had a good reputation, but it was not entirely justified.

We found information about Jewish life in France from a number of different sources. For example, in her book Tombeaux, Autobiographie de ma famille (Tombs, an autobiography of my family), published by Seuil in 2022, French historian and author Annette Wieviorka paints a picture of Jewish families who came to France in the late 19th century. She describes how the parents found it difficult to integrate due to the language barrier and restrictions on working in certain trades, in particularly the clothing industry, while the children integrated more easily, through school and further education, and often went on to find “skilled” and “professional” jobs.

In fact, France was the first country to grant Jewish people equal rights. The National Assembly voted in favor of this change in September 1791, at the very beginning of the French Revolution. It was followed by a series of laws that also granted Jewish people citizenship elsewhere in Europe, a move that is known as the “Jewish emancipation.”

However, no matter how well-integrated the Jews were, a number of anti-Semitic movements began to emerge.

The Dreyfus affair, for example, which took place from 1894 to 1906, highlighted the extent of anti-Semitism in French society at the time. Similarly, the Great Depression fueled a growing sense of mistrust in the Jews. People even accused Jews who had arrived in France after the First World war, most of whom worked in the clothing trade or in the industrial sector, of taking French people’s jobs.

Over the years, the far-right and the anti-Semitic press had been gaining ground in France, spreading xenophobic ideologies and accusing Jews of being disloyal to the country. The same trend can be seen in many other European countries as well.

c) Jeannine Akoun between 1928 and June 1940

We can only imagine how happy the couple were to be blessed with a baby girl, and how they must have been looking forward to their new life as a family. Sadly, however, Reine-Esther died three years after Jeannine was born. No details are available about the cause of her death. Chemouël was therefore left to raise Jeannine on his own.

We suppose Jeannine started school around 1934, when France introduced legislation known as the Ferry laws, which made education compulsory from age 6 to 13. As a result of pressure from feminist movements in the 1910s, girls’ education had been brought more into line with that of their male counterparts. They were taught the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic. We know that there were also separate classes for girls, geared towards domestic education. They were taught how to keep house and cook as part of their schooling.

We would have loved to know a little more about what Jeannine enjoyed most: what were her favorite subjects? What games did she play in the schoolyard? Did she have a hobby or interest outside school, such as drawing or music? Unfortunately, the Vichy police did not keep records of this sort of information.

Jeannine grew up in the 1930s. She would have been too young to know about the increasing anti-Semitism in Europe. The Dreyfus affair, which took place 30 years earlier, had paved the way for anti-Jewish sentiment in France. Newspapers such as “Action française” and “Gringoire”, published despicable articles about the Jewish community, and well-known French authors such as Céline expressed overtly anti-Semitic views.

In short, we know very little about Jeannine Akoun’s early years, other than a few official records, so all we can do is surmise what her life must have been like.

2. The Second World War: Jeannine Akoun during the Holocaust

The Second World War began on September 1, 1939 , when Nazi Germany invaded Poland; soon afterwards, France declared war on Germany. Was Chemouël Akoun called up to fight in the war? He was born in 1888, so would have been 51 years old by then, and thus may not have been mobilized on account of his age.

The German occupation of France began on June 20, 1940, two days after France surrendered. Jeannine was 11 years old. In late September of that year, the first anti-Jewish measures were put in place.

On October 2 the “law relating to foreign nationals of the Jewish race” was enacted. Jeannine and her father were not affected by this, since although they were Jewish, they were French, rather than foreign citizens. The decree made provision for foreign Jews to be interned, and also heralded the beginning of the Vichy regime’s policy of collaboration with the Germany, which ultimately helped the Nazis in their efforts to exterminate all the Jews in Europe.

The following day, October 3, the first law on the status of the Jews was enacted. It stated:

“any person who has three grandparents of the Jewish race or two grandparents of the said race if his or her spouse is Jewish” shall be regarded as a Jew”

This time, the Jeannine and her father were included in the criteria. The decree also banned the Jews from working in a number of professions. Both laws came into effect on October 18, 1940. Jeannine Akoun was twelve years and two months old when the French State deemed her to be “vermin to be disposed of”. This wording was reiterated and revised in another decree on June 2, 1941.

a) The Vichy regime and its anti-Semitic policy

The Vichy regime ruled France from July 1940 to August 1944. It was a essentially a dictatorship, led by Marshal Pétain, the “Victor of Verdun”, who was very popular when he first came to power.

The Vichy government adopted a new political ideology: the “National Revolution”.

Marshal Pétain, as the Head of State, replaced the fundamental Republican values of “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” with “Work, Family, Homeland”). His intention was to “revolutionize” French society and the State, which accounts for the Vichy regime’s focus on new legislation: it passed 16,786 laws and decrees over the four years that it remained in power.

The regime began compiling a body of legal principles designed to provide the framework for the “National Revolution”, and right from the outset, the laws made it clear what direction it would take: the introduction of measures which, under the guise of broad-based xenophobia, were aimed primarily at the Jews.

The regime began compiling a body of legal principles designed to provide the framework for the “National Revolution”, and right from the outset, the laws made it clear what direction it would take: the introduction of measures which, under the guise of broad-based xenophobia, were aimed primarily at the Jews.

Numerous laws were passed in a very short space of time: in just three months, between July 10 and October 18, 1940, the French state adopted its anti-Semitic policy, an integral part of the “National Revolution”, the foundations of which were largely inspired by the “Action Française” movement.

In Vichy, in the Allier department of France, where the government set up its headquarters on July 1, there was a “surge of anti-Semitism”, as Emmanuel Berl put it in his book “La fin de la IIIeme République” (The End of the Third Republic). It became increasingly apparent in the corridors of power and during National Assembly sittings.

On October 18, 1940, the keystone of the anti-Semitic program, the decree of October 3 on the “Status of the Jews”, was made public. The Vichy government officially declared that it was a sovereign project, aimed at the entire Jewish population in France, regardless of their nationality, since it viewed the Jews as a major problem. This approach was very much in line with the French anti-Semitic discourse of the 1930s, during which the far right repeatedly decried both the “Jewish invasion” of the country and the Jews’ “stranglehold” on power, particularly after the Front Populaire (National Front) won the election.

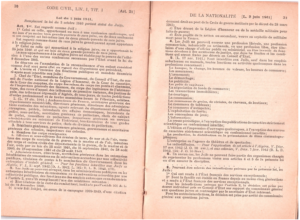

The image above is an extract from the French Civil Code, 1944 edition, law of June 3, 1941, which defined who was deemed to be a Jew (article 1), prohibiting Jews from working in public institutions and from being elected to official positions.

Although it based its legislation on the Nazis’ Nuremberg Laws of September 1935, the Vichy regime acted on its own initiative. The Germans did not force it to make these laws. Again, this demonstrates both Marshal Pétain and the Vichy regime’s underlying anti-Semitism.

In fact, the new regime opted for a policy that blended tokenism with legislation, adopting measures that sent clear signals to both supporters of anti-Semitism and the Jews themselves.

For example, on July 14, 1940, the Vichy regime refused to send a representative to the French National Holiday (sometimes called “Bastille Day” in English) celebration at the local synagogue. Then, as regards culture and freedom of expression, Radio Nationale, the French National radio station, took the religious broadcast “La voix d’Israël” (The Voice of Israel) off the air. Just a few weeks later, it was replaced by a program hosted by two journalists from “Je suis partout” (I am everywhere), Alain Laubreaux and Lucien Rebatet, in which they indulged in their anti-Semitic rhetoric.

In the summer of 1940, other legislation (such as the decree governing eligibility for ministerial cabinet appointments) made access to certain jobs conditional on candidates having “pure French blood”.

Only people born of non-Jewish parents were eligible, mirroring the demands of the anti-Semites in the 1930s. Thus, in keeping with this approach:

- It was forbidden for any person who did not hold “original French nationality, having been born of a French father” to work in the public sector.

- Some Jews’ French nationality was revoked, and naturalizations granted since 1927 were reviewed, in line with a Nazi law passed in 1933.

The intended target of such initiatives was never in doubt: it was “the Israelites” (Jews). But the Vichy government wanted to pursue its anti-Jewish policy at its own pace, in stages, without upsetting the public, as it was unsure of how people might react. The legislative framework swiftly put in place during the summer was intended to pave the way for a much more far-reaching project.

b) Jeannine Akoun’s day to day life under the Vichy regime

Starting in the summer of 1940, Jeannine Akoun and her father, along with all the other Jews living in France, were seriously affected by this series of new laws. They suffered harassment and were subject to restrictions that affected their everyday lives. They were:

- Banned from owning radios, bicycles and dogs

- Banned from having a telephone in their home

- Forbidden to enter public parks, gardens and squares

- Obliged to travel in the last car on the subway

- Only allowed to do their shopping between 3 and 4 p.m.

In addition, the French Civil Code forbade them from working in many professions. Not only that, but the noose was tightening around foreign Jews. The Germans were putting pressure on the Vichy government to hand over Jews to them. The government, however, was reluctant to hand over French Jews for fear of public backlash , so it initially focused its efforts on foreign Jews. The French authorities began rounding up and arresting Jews in order to hand them over to the Germans.

The “Green ticket” roundup:

On May 14, 1941, during what became known as the “green ticket” roundup (named after the color of an official form), 6,494 stateless Jews, all men, were summoned to the police department in Paris, for a “status review.” 3,747 of them complied, some accompanied by family members. They were arrested on the spot and transferred to the Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande camps in the Loiret department of France.

The “Vel’ d’Hiv’” roundup:

On July 16 and 17, 1942, the French police arrested 12,884 Jews in Paris. They included 3,031 men and 5,802 women, most of them stateless, and 4,051 children under the age of sixteen, almost all of them French citizens. Around 5,000 adults who did not have children with them were taken to Drancy camp, north of the city. The families were held at the Vélodrome d’Hiver (winter cycling track), where they were left unattended and with hardly any food. They were then transferred to camps in the Loiret department, after which they were separated and the adults were deported. The children were left behind, abandoned to the occupying forces by the Vichy regime. They too were eventually deported.

Roundups in the southern zone:

On August 26, 1942, the Vichy regime initiated a series of roundups of stateless Jews in the unoccupied “free” zone in the southern half of France: 6,600 men, women, and children were arrested. Around 6,500 of these “stateless” Jews were arrested that day or over the next few days, in addition to over 3,500 Jews who had been recently transferred from camps for Jews in the free zone. Not everyone in the “free” zone was truly free. Between August 6 and October 22, 1942, seventeen trains were used to transfer some 10,500 Jews to Drancy camp. From there, they were deported to Auschwitz on Convoys 17 to 42.

Beginning in 1940, both the Vichy government and the Nazi occupiers adopted anti-Semitic policies, each using different methods. In the case of Marshal Pétain’s regime, these included xenophobic practices such as the internment of foreigners of the “Jewish race”, the removal of French citizenship from Jews who had been naturalized in the past and the introduction of forced labor in “foreign workers’ groups”.

From 1942 onwards, the Nazis’ applied their genocidal policy to all Jews. As part of the collaboration, the Vichy regime harnessed the power of the State to help perpetrate this crime. The regime, which was both anti-Semitic and xenophobic, chose to hand over stateless people, foreigners and their children born in France first. After the German forces invaded the southern zone in November 1942, the authorities cracked down on all Jews, regardless of their nationality. Foreigners, the first to be sacrificed and the least well integrated, were the hardest hit: 40% of foreign Jews and 16% of French Jews were deported and murdered.

Jeannine and Chemouël Akoun avoided the first few roundups. However, their legal situation had changed. Although Jeannine was a French citizen, her father had been stripped of his French nationality when the Crémieux decree was repealed in October 1940. They therefore lived under the constant threat of arrest if they did not behave in accordance with the new laws. The French authorities and the police played a central role in this (Laurent Joly, “La rafle du Vel d’hiv”). In fact, it was the French authorities who organized the census, arrests and convoys, only handing the prisoners over to the Germans when they left Drancy camp.

b) Gaston and Jeannine Akoun’s experiences in Vichy-ruled France

On May 29, 1942, the Germans issued an order requiring all Jews aged 6 and over living in the occupied zone to wear a yellow star.

To collect the star, Jews had to go to a police station where, in exchange for a textile ration coupon, they issued with three stars each. In other words, the Jews were made to pay for the symbol that served to identify and stigmatize them.

Jeannine and her father were not exempt from this rule, so had to go to their local police station to collect their stars.

We have not been able to determine whether Chemouël Akoun was still able to work at that point. Before the war, he worked as a clerk, a job that was not listed as forbidden in the decree on the status of Jews. But was he able to keep his job, did his employer seek to protect him or, conversely, did he lose his job as a result of the anti-Semitism instigated by the Vichy regime?

Chemouël and Jeannine were therefore obliged to wear the yellow star that distinguished Jews from the rest of the population.

Chemouël, along with many other people, did not, or did not always, comply with this requirement. Whether he refused to wear his star or simply forgot one day, we shall never know, but in November 1943, he was arrested for not wearing it.

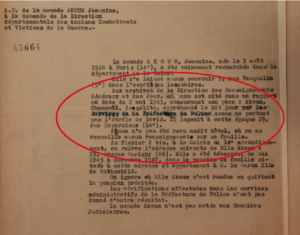

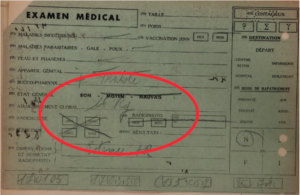

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, Dossier 21P696210

His failure to wear it resulted in him being brought before a judge, as Johanna Lehr explains in her book Au nom de la loi, la persécution quotidienne des juifs à Paris sous l’occupation (In the name of the law, the daily persecution of Jews in Paris during the Occupation). Once the offence had been proved, he was handed over to the police and then taken to Drancy.

What happened to Chemouël Akoun was the same as for everyone else in his position. He was caught in a web from which there was no escape, and which led inexorably to his tragic fate. Once arrested and brought before the judge, he was handed over to the Drancy authorities in charge of deportation, just as Johanna Lahr says.

After being interned in Drancy, he was deported on Convoy 62 to Auschwitz, from which he never returned.

However, what was happening to the Jews was met with disapproval on the part of many French people. Some of them sought to hide and protect the Jews, often because they were friends or neighbors or friends, but sometimes simply due to their moral beliefs and convictions.

Some public figures spoke out too, particularly after the Vel d’Hiv roundup, to condemn the Vichy government’s anti-Semitic policies. For example, Cardinal Saliège, the Archbishop of Toulouse, had the following letter read out in all the churches in the diocese.

LETTER FROM HIS EXCELLENCY THE ARCHBISHOP OF TOULOUSE ABOUT THE HUMAN PERSON

“Dear Brothers,

There is a Christian morality, a human morality, which assigns duties and recognizes rights. These duties and rights are part of the very nature of mankind. They come from God. They can be violated. No mortal has the power to suppress them.

That children, women, men, mothers and fathers should be treated like a filthy herd, that members of the same family should be separated from each other and shipped off to an unknown destination, this sad spectacle has never been seen before.

Why does the right of asylum in our churches no longer exist?

That children, women, men, mothers and fathers should be treated like a filthy herd, that members of the same family should be separated from each other and shipped off to an unknown destination, this sad spectacle has never before been seen.

Why does the right of asylum in our churches no longer exist?

Why are we so defeated?

Lord have mercy on us.

Our Lady, pray for France.

Here, in our diocese, horrific scenes have taken place in the camps at Noé and Récébédou. Jewish men are men, Jewish women are women. Foreigners are men, foreigners are women. It is not allowed to do just anything to them, to these men, to these women, to these fathers and mothers. They are part of the human race. They are our brothers, just like so many others. A Christian cannot forget this.

France, our beloved homeland, France, which instils in the conscience of all your children the tradition of respect for the human person, chivalrous and generous France, I have no doubt that you are not responsible for these horrors.

Please, my dear Brothers, be assured of my respectful devotion.

Jules-Géraud SALIÈGE

Archbishop of Toulouse

To be read out next Sunday, without further comment”.

Monsignor Saliège only narrowly escaped being arrested as a result of this letter.

c) Jeannine Akoun after her father was arrested: from her own arrest to deportation to Auschwitz and then to Kratzau

Jeannine was 15 years old in 1944, when she was arrested at 9, rue Vauquelin in Paris.

She was very probably taken in at the children’s home on rue Vauquelin after her father was arrested, when she was left alone and destitute in Paris. We can only imagine how this fifteen-year-old girl must have felt, left to fend for herself. However, we do not know for sure how she ended up there.

We have seen and heard testimonies from other women who suddenly found themselves isolated like this, left to their own devices. How and where could they find food, where could they sleep? We were particularly struck by the story of one young girl who wandered the streets of Paris alone for two weeks before she went to see her father’s former business partner, and how he turned her away.

The solution, for Jeannine, must have been to turn to the Jewish organizations that played such an important role during the war. A protective role in theory, but one which, in this case, turned out to be a trap.

The home on Rue Vauquelin was run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites en France, or General Union of French Jews). It’s aim was to document as many Jews as possible who were living in France, supposedly in order to be able to find them more easily and help them if necessary. However, it had been founded on the orders of the Germans, whose real intention was to use it to pursue their extermination policy. Children’s homes were deliberately targeted as part of this policy, as was the case at the Maison d’Izieu, for example.

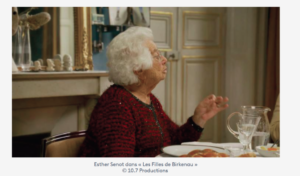

When we watched David Teboul’s documentary “Les filles de Birkenau”, with contributions from Ginette Kolinka, Esther Senot, Judith Elkann and Isabelle Choko, we learned more about what Jeannine went through. The women recount their lives during the war and what happened to them when they were deported. We found Esther Senot’s testimony particularly interesting, as she spoke about the home on rue Vauquelin, where she too stayed in 1943. She explained how she and other young girls were sent out to do food shopping in the local neighborhood. They were able to go out despite the danger. We wonder if Jeannine’s time in the home was similar?

On July 21, 1944, early in the morning, the Gestapo burst into the home on Rue Vauquelin and arrested everyone who was there at the time. Jeannine and her friends were taken to Drancy camp, where they were interned until they were deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, on Convoy 77.

These arrests took place just a month before Paris was liberated!

We have no direct information about Jeannine’s time in Drancy, but we can imagine what happened to her after she was arrested, based on a testimony given by Suzanne Boukobza in 2016. Suzanne was deported on the same convoy as Jeannine, whom she knew, and they went through the horror of the concentration camps together.

Right from the start, In Drancy, living conditions were terrible. It was the height of summer and extremely hot. Suzanne Boukobza talked about how there was very little food and how unhygienic it was.

The girls were deported on the last large convoy from Drancy, and the journey to Auschwitz took three days. When they arrived, they were met with violence and horror, with dogs barking and Germans beating them. During the selection, Jeannine and her friends were deemed fit to work and sent into the concentration camp. A French man who had been deported previously and was on the ramp when they got off the train had told them to stick together and not show how exhausted they were after the journey.

Sent into the camp to work, they were first shaved, shorn, tattooed and disinfected, and then taken into the Birkenau camp.

The kapos who supervised the girls forced them to work hard. Ginette Kolinka and Denise Hostein recalled that the tasks they were given were meaningless, involving moving things from one place to another, then moving them back again the next day. It was exhausting work and they were given very little to eat; Ginette Kolinka described her main meal of the day as “a slice of bread with a knob of margarine” and said they had to be careful not to have their food stolen. The female guards were extremely violent and Jeannine and her fellow prisoners also lived under constant threat of being subjected to Dr. Mengele’s infamous experiments or even being killed.

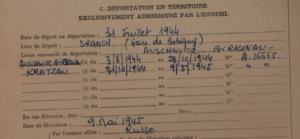

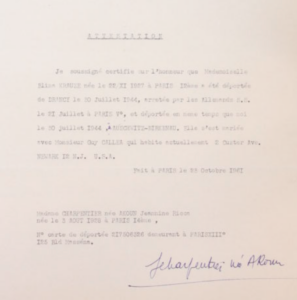

The application that Jeannine put together after the war to request the status of “political deportee” relates her journey through the concentration camps, from Drancy right through to when she was liberated.

It also includes the number that was tattooed on her arm: A 16665.

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

On October 31, 1944, Jeannine was transferred on an open train to another camp, this time in Kratzau, Czechoslovakia. There, she worked in an armaments factory until she was exhausted, even though the civilians who worked in the factory helped her and her fellow prisoners as best they could, by giving them small amounts of food, among other things. Suzanne Boukobza said that life in Kratzau camp, although hard, was not as bad as it had been in Auschwitz.

In May 1945, after the camp was liberated by the Russian army, Jeannine and her group made their way to the American-controlled zone and then returned to Paris.

By the time she got back Jeannine was very thin. Her medical report card states that she had lost 35 pounds.

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

She never saw her father again: he had been murdered in Auschwitz.

d) Jeannine’s return to France

When she returned to France, Jeannine was once again taken in by a Jewish organization. She was placed in a home in a mansion across from the Élysée Palace in Paris, which belonged to the Rothschild family. We do not know how long she stayed there.

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

It seems to have taken a long time for the authorities to address Jeannine’s situation.

The Holocaust and the Resistance: two overlapping memories, still in the making

After the war, the question arose as to the position of Jewish deportees in the history of World War II. At the time, there was no means of differentiating between the various reasons for which people were deported.

One poster, for example, portrays deportees and prisoners of war on an equal footing, and makes no attempt to distinguish “political” from “racial” deportees. As a result, politically-inclined resistance fighters played a central role in rebuilding the country and its political structure, while the other Holocaust survivors were left out of the picture and gradually disappeared from view.

Source: histoirencours.fr

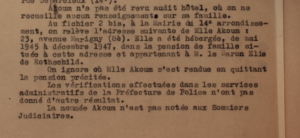

The authorities tried to locate Jeannine in the late 1940s, but to no avail.

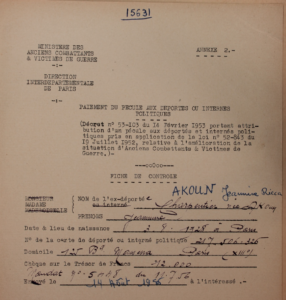

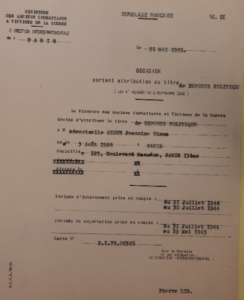

When the Ministry of Veterans and War Victims opened a file on Jeannine Akoun on May 31, 1955, exactly ten years after the end of the war, it was stamped “political deportee.”

This is reflected in Jeannine Akoun’s own application. While there is no mention of her being deported on account of her Jewish roots or the Vichy regime’s anti-Semitic policies, she was nevertheless officially acknowledged to have been a “political deportee.”

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

On this page from her file, dated 1956, which records a small compensation payment, the reason given is that she was a “political deportee or political internee,” but there is nothing to say that it was race-related.

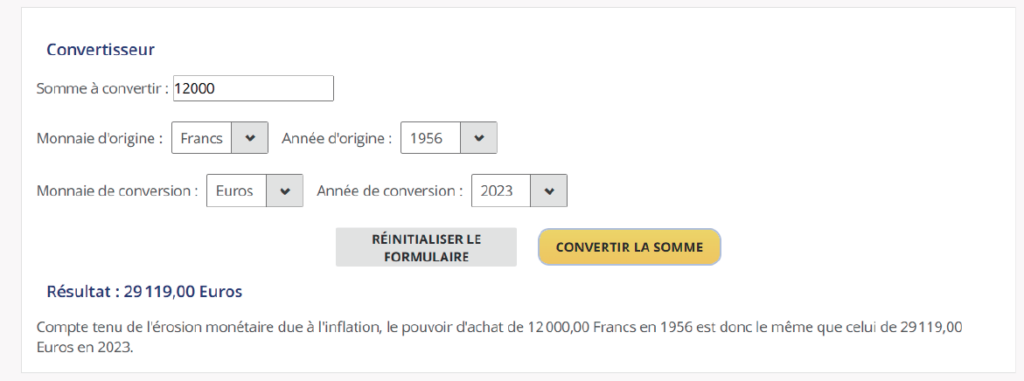

We wanted to find out how much the 12,000 francs Jeannine received in 1956 would be worth today, so used the conversion tool on the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) website:

The amount Jeannine received appears to be “significant”. However, we do not know how it was arrived at. What criteria were taken into account?

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

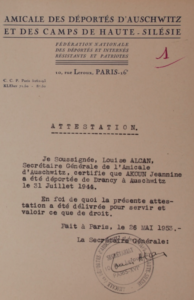

We also know from the records available to us that it was not easy for her to have her status as a former deportee officially acknowledged.

She had to prove that she had been deported.

This is no doubt why she had the “Association of Deportees from Auschwitz and the Upper Silesia Camps” issue her a certificate.

Her application also enables us to catch up with what was happening in her life at that time. She was living in a low-rent apartment at 125 Boulevard Massena in the 13th district of Paris. We do not know whether or not the fact that she had been deported was taken into account when she was allocated the apartment.

The apartment block at 125, boulevard Massena, where Jeannine Akoun lived

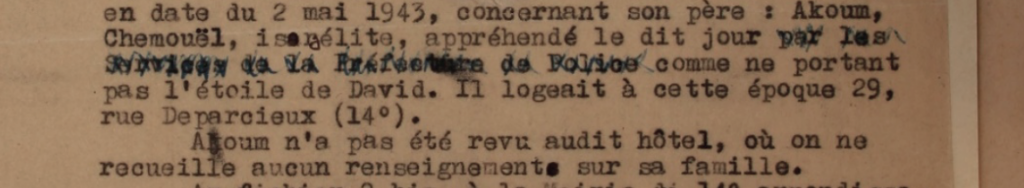

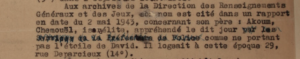

Something else had us a little confused. The report about Chemouël Akoun’s arrest, dated December 7, 1948, caught our attention. It said he was arrested by the “police department”, in other words the French authorities.

However, this part has been crossed out, suggesting that he was in fact arrested by the Germans. This also highlights how uneasy the French were about who had arrested the Jews during the war. It was a time when “Tous résistants” (“We are all a part of the Resistance”) was being championed by political parties as part of post-war political reconstruction. We can thus conclude that at that time, there was little or no attempt to address the role of the French in the atrocities that took place during the Holocaust.

However, this part has been crossed out, suggesting that he was in fact arrested by the Germans. This also highlights how uneasy the French were about who had arrested the Jews during the war. It was a time when “Tous résistants” (“We are all a part of the Resistance”) was being championed by political parties as part of post-war political reconstruction. We can thus conclude that at that time, there was little or no attempt to address the role of the French in the atrocities that took place during the Holocaust.

Jeannine seems to have vanished for a while after the war. The authorities began searching for her in the 1950s, possibly with a view to paying her compensation. They made inquiries at the various homes where she had been reported to have lived during the war: rue Vauquelin, rue de l’Élysée and rue Deparcieux. The search proved fruitless, however, as can be seen from the following report.

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

There is no record of how they found her in the 1950s, when the compensation was paid.

125, boulevard Massena was a low-rent housing development built in the 1930s on the site of some old fortifications. It was, and still is, in a working-class area. She did not move from there for many years, and was in fact still living there in 1961.

Her application for deportee status was a long and complicated process (she was even asked to provide a birth certificate!), but eventually, on May 31, 1955, she was officially acknowledged to have been deported and was issued a political deportees’ card numbered 2.1.75.06326.

We also know that she married a man called Pierre Charpentier, who was a baker, and that they had a daughter, who died before Jeannine, sadly.

Jeannine Akoun © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21P696210

3. Jeannine’s life after she was deported: between fitting back in and being forgotten

a) The increasing importance of the Holocaust in the memory of the Second World War

After the war, the Jewish victims were largely forgotten, while the deported Resistance fighters were widely remembered. However, over time, the Holocaust has become better known and its victims commemorated, and is now a major part of the French “duty to remember”. This was a slow process however, and other countries’ approaches differ.

Germany, after the Nuremberg trials, went through a period of silence and repression as regards its responsibility for the Holocaust. It was not until the late 1950s, when a number of anti-Semitic incidents took place in the country, that the German population became increasingly mindful of the Holocaust. But it was not until 1961, when details came to light during Adolf Eichman’s trial, that the collective memory of the Holocaust shifted. For the first time, sixteen years after the war ended, Jewish survivors were given a genuine voice. The subsequent “Auschwitz” proceedings in Frankfurt placed the emphasis on the criminal actions of the state as a whole and the crowds that had supported it, rather than on individual responsibility as had previously been the case. In what was then West Germany, the statute of limitations on Holocaust-related crimes was dropped, and the subject was taught in schools from 1962 onwards. Little by little, the legacy of the Holocaust spread throughout West German society, and many books, documentaries and films were made on the subject. Chancellor Willy Brandt knelt in front of the Warsaw Ghetto memorial in 1970, the Jewish Museum in Berlin opened in 1998, and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe was inaugurated in 2005, sixty years after the war.

It was different in the Communist countries, however, and it was not until the dictatorships came to an end and free elections were held in the 1990s that the German Democratic Republic (the former East Germany) acknowledged its responsibility for the Holocaust, and the first studies and commemorations began. Until then, the communist countries commemorated the victims of the Nazis as proletariats, antifascists or communists, but made no mention of their religion or nationality.

In France too, remembering the Holocaust was a lengthy process. After an almost total silence in the post-war period, the first Holocaust-related research initiatives emerged in the 1950s. In 1956, the Tombeau du martyr juif inconnu (Tomb of the Unknown Jewish Martyr) was erected in Paris. Dedicated to all the Jews of Europe who were annihilated, it was the first Holocaust memorial in France.

It was not until the 1970s, however, in response to the emergence of Holocaust denial, that the Jews became more militant and began to articulate their own memories of events. Increasing numbers of former deportees spoke out and gave testimony. Film and television also played an important role, with a 1979 soap opera called Holocaust (1979) and in particular Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 film Shoah, which was based entirely on eyewitness accounts.

The freedom of witnesses to speak out, artistic works and activists’ campaigns (such as those of Serge and Beate Klarsfeld), along with work by historians, all contributed to a greater public awareness of what happened to the Jews. On July 16, 1995, French President Jacques Chirac acknowledged the responsibility of the French state and authorities for the persecution of the Jews of France. In 2000, the French parliament voted to introduce a national Holocaust Remembrance Day, and the Shoah Memorial in Paris was inaugurated in 2005.

However, Holocaust remembrance has also extended well beyond Europe, with the inauguration in October 1947 of the very first memorial to the Jews in the United States, where film documentaries and movies have played a key role in raising public awareness of the Holocaust.

In Israel too, while at first there was little mention of Jewish Holocaust victims (Zionist views were at odds with the notion that the Jews were powerless during the Holocaust) the Six-Day War and then the Yom Kippur War raised fears of a repeat of the genocide, thus reconciling Zionism with the memory of the Holocaust. In the 1950s, the Israeli parliament introduced Yom HaShoah, (Holocaust Remembrance Day) and founded the Yad Vashem Memorial, which holds the world’s largest collection of Holocaust-related documentation.

The Holocaust has thus become an ever more important aspect of our collective memory of the Second World War, culminating in 2002 with the designation of an International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust.

b) The last few traces of Jeannine Akoun

It appears that Jeannine, unlike several of her fellow deportees, had no desire to bear witness to what she had experienced during the war and her time in the camps. She is mentioned occasionally in testimonials given by other deportees from the same convoy, but she does not seem to have played an active role in passing on her experience. There is one record, however, dating from 1961, which shows her support for a fellow deportee.

We got in touch with Ms. Laferrière and Mr. Coustal, who teach at the Bourg Chevreau high school in Segré, in the Maine-et-Loire department of France. They and their students had worked on the biography of another Convoy 77 deportee, Blima Krauze. The two women must have been in contact in October 1961, as the school sent us a copy of a sworn statement in which Jeannine Akoun confirmed that she was deported together with Blima Krauze in July 1944.

This is the most recent trace we could find of Jeannine Akoun. At the time, she was still living at 125 boulevard Massena, in the 13th district of Paris.

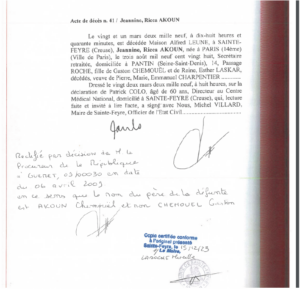

Jeannine Akoun died on March 21, 2009 in the Alfred Lejeune care home in à Sainte Feyre, in the Creuse department of France.

We had thought for some time that she may have moved to the Creuse because her husband’s family came from there. This does seem to be the case since she was living in the retirement home there when she died. That said, her death certificate states that she was officially living at 14, passage Roche in Pantin, in the north east of Paris. We did not contact the retirement home to investigate further.

14, passage Roche, in Pantin, in the north east of Paris

In addition listing her address in Pantin, which was then a working-class neighborhood but is now undergoing complete renovation, her death certificate also gave us her occupation, which is listed as “secretary”.

It appears that her daughter had no children. We thought of searching under the name Charpentier, but it is a very common name.

Our teacher, Mr. Ivanoff went to the cemetery in Saint Feyre in search of Jeannine Akoun’s grave, but he found nothing.

Two photos of the cemetery in Saint Feyre, where Jeannine Akoun died in 2009

Bibliography

- Tombeaux, Autobiographie de ma famille, Annette Wiewiorka, published by Seuil, 2022

- L’Etat contre les Juifs, Laurent Joly, published by Grasset 2018

- La rafle du vel d’Hiv, Laurent Joly, published by Grasset 2022

- La France et la Shoah, Laurent Joly, published by Calmann Lévy 2023

- La survie des Juifs en France, 1940-1944, Jacques Semelin, published by CNRS 2018

- Au nom de la loi, La persécution quotidienne des Juifs sous l’Occupation, Johanna Lehr, NRF 2024

Notes and references

[1] From this article, in French, from the nonprofit organization L’enfant et la Shoah (Children and the Holocaust) https://lenfantetlashoah.org/wp-content/uploads/TELE-EJP/YL-ENFANTS-JUIFS-A-PARIS-FICHES.pdf

[2] The 11th district of Paris – Wikipedia

[3] Dora Bruder, in Patrick Modiano, Romans, quarto Gallimard P. 648

Français

Français Polski

Polski