Léon GELBCHAR

“These are yesterday’s stories, but then again, life is always the same, so this one-time tragedy could happen again.” [1] This sentence by Boualem Sansal sums up our philosophy perfectly, and it was this that prompted us to become involved in the Convoy 77 project.

We (Katie Ennon, Amarine Bernard, Prudence Moreau and Mathilda Cordaro) are four high school students from the Victor Hugo high school in Poitiers, in the Vienne department of France. We decided write a biography of Léon Gelbchar. At the suggestion of our History, Geography, Geopolitics and Political Science teacher, and thanks to the initiative and advice of a student from the Political Science School (Carla Spodek), we were able to take part on a more personal level in this historical project that pays tribute to the victims of the Holocaust. At the same time, we discovered more about the past in our local area, following in the footsteps of a child from Poitiers. It was important to us to revive the memory of the Jews, while at the same time, as part of a small group, carrying out our duty to pass on the memory of the Holocaust. We hope that our participation in this research will ensure that we never forget to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive.

Before we begin telling this life story, we would like to mention that as part of our research work, we used scanned records provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit organization as well as documents sent to us by the Vienne departmental archives. We also drew on the work of two historians: Paul Lévy’s book about the camp on the route de Limoges in Poitiers, and Jean Laloum’s research on the U.G.I.F. children’s homes. We were also able to add to the content by listening to the testimonies of several witnesses: first of all, Ginette Kolinka, who came to meet us in our high school, and then videos of Félicia Barbanel-Combaud, Esther Senot and Elie Buzyn. Some of us also read Elie Wiesel’s book, La Nuit (The Night)

I. Léon’s childhood in Nancy

Léon Schmir Gelbchar, the son of Srojzeck Gelbchar and Mincha Wladiminska, was born at 5pm on October 19, 1932 at 9bis rue de Strasbourg in Nancy, in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France[2]. Léon was the oldest of three boys. His brothers were Isidore, who was born in Nancy on February 8, 1935, and Henry, who was born in Sansay on June 6, 1941. His father, a tailor, was born on July 15, 1904, and his mother, who did not work outside the home, was born on March 27, 1905. They were both Polish and were married on March 1, 1937 [3]. The family, which was Jewish, lived on rue de la Hache in Nancy. However, when Germans occupied the Meurthe-et-Moselle department soon after the war began, they had to face up to living under military rule. In fact, during the Holocaust, French Jews in this area were treated in the same way as to as the Jews in Germany.

It was in this context that 76,000 Jews, 11,000 of them children, including the Gelbchar family, were deported and murdered by the Nazis. When they found themselves living under German Occupation, Léon’s family therefore did the same as many other local families, and fled to the Vienne department, which was in the “free zone” in the southern half of France, in order to escape the Nazis. They lived at 18 rue Sylvain Drault in Poitiers, where they were subsequently arrested.

On the left, a present-day photo of 18 rue Drault.

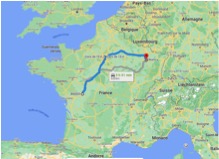

On the right, the route that Leon and his family took when they moved from Nancy to Poitiers.

II. Léon’s internment in the Poitiers camp

“They came to our house, […] we were told not to ask any questions and then off we went. There had been no arrests in Vienne before this. We had no idea what was going on. When we arrived at the camp, it was dirty, it was horrendous”. This extract from an interview by survivor Felicia Barbanel-Combaud for the INA (the French National Audiovisual Institute)[4], was invaluable, in that it helped us to better understand what Léon went through in this camp, which was a kind of “antechamber to the Holocaust”. Félicia, like Léon, came from a Jewish family in Nancy who had fled to the Vienne to escape the Germans and was then interned in the camp on the Limoges road in Poitiers. Until December 4, 1940, only Spanish Republican refugees had been held in barracks (alongside the road from Limoges to Poitiers). It was then decided that Gypsies, Nomads and Jews would all be held in the same place. The camp on the Limoges road was to be run by a number of different managers, and regularly monitored by an inspector general, who sometimes criticized the living conditions in the camp, but at other times did not. It was they who were responsible for transferring Jews to Drancy and deporting them for forced labor. In July 1942, on the orders of the German authorities, the French National Police undertook a census, which the Prefect requested should include children, one of whom would no doubt have been Léon Gelbchar. He was first sent to the Limoges road camp in Poitiers on October 9, 1942, but was provisionally released 6 days later, on October 15. On May 24, 1943, he was taken back into the camp, and then transferred to Paris, together with his brother Isidore, on May 26.

Paul Lévy’s research [5] into the Limoges road camp explains the living conditions that Léon had to endure during his few days of internment. In particular, we learn that the internees were undernourished, and the living conditions were unhealthy, as most of them were riddled with lice.

In addition, the camp budget was insufficient to buy any new clothing. As a result, internees wore ragged clothes and wandered around the camp barefoot, despite some help from the French national aid organization, the Secours Nationaux.

In response to this situation, the Ministry of the Interior, in 1941, allocated funds to the camp to cover the cost of housing nomads and people to be expelled but, despite a visit from the Minister of Finance at the time, the funds were never paid out. However, the Limoges road camp did receive some help from Father Fleury and Rabbi Elie Bloch. It was Father Fleury who taught the class for Jewish and Gypsy children of all ages that was set up in the camp in 1941, with no teaching materials whatsoever. In 1943, despite official reports to the contrary, the class was no longer open to Jewish children. Léon may have benefited from a few days of schooling during his first internment in 1942, but not in 1943, as he was no longer eligible to attend.

A note from the manager of the U.G.I.F. (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) in Paris mentions that Léon arrived in Paris from the Limoges road camp, with no food ration card or coupons. The manager therefore requested ration cards from the head of the supply department in the 15th district of Paris, because he was unable to feed them.

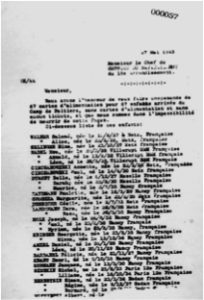

Note dated May 1943, stating that children who had been transferred from the Poitiers camp to Paris had no food cards.

III. Léon and his brother Isidore’s transfer to the U.G.I.F.

List of Jewish children transferred from Poitiers to Paris

on May 26, 1943.

On July 31, 1944, less than a month before Paris was liberated, one of the largest deportation convoys of Jews from France left Drancy for Auschwitz. Convoy 77 was made up of 1,300 people, including 300 or so children, most of them taken from U.G.I.F. children’s homes in and around Paris. “The Jews who worked for the U.G.I.F. thought they would be able to save Jews, but they only realized much later, by which time it was too late, that the U.G.I.F. had turned out to be a trap for some of them, for those they had taken in,” explained Antoine Vitkine.

In fact, through the prefectures and the Gestapo, all Jews were required to join the U.G.I.F. All pre-existing Jewish organizations were disbanded. The U.G.I.F. ran its own children’s homes, founded on July 16 and 17, 1942, at the time of the Vel d’Hiv roundup. Children “liberated” from the camps at Drancy, Pithiviers, Beaune-la Rolande and Poitiers were placed in U.G.I.F. homes. Léon was one of the so-called “blocked” children who were taken care of by the U.G.I.F. Their names were listed in a specific police register: “These very particular liberations were in reality fictitious.[6] These children were always sent to U.G.I.F. homes and placement decisions were made by the German authorities. The Germans and Vichy authorities had complete control over these children. The children were distributed among the various UG.I.F. facilities: Montreuil, the Rothschild orphanage, the Zysman boarding house in La Varenne, Saint-Mandé, Neuilly, Paris, rue Vauquelin, at the vocational school on rue des Rosiers and at Louveciennes, where Léon stayed.

List dating from October 1943 of children transferred from the Louveciennes La Varenne children’s homes

IV. The transfer to Drancy and deportation to Auschwitz.

The first transfers to Drancy took place on July 15, 1941. It was two years later when the German trap began to close around the Jewish children who had been assembled in the U.G.I.F. homes. The Nazi police, instructed by the German authorities, wrote to the Police Superintendent in Poitiers on May 13, 1943, “requesting security measures and rapid execution of the action in absolute secrecy”In the belief that the Germans would soon withdraw from Paris, he wanted to deport as many Jews as possible before they retreated. The French police and military police were called in to round up some families (see list further down) including 70 children and 45 adults. The Poitiers Prefecture sent a telegraph, signed by Secretary General E. Simonneau, to the Chief of Police in Paris, informing him that a convoy would be leaving Poitiers at 5 a.m. on Wednesday May 26 and arriving at 4 p.m. at the Austerlitz train station in Paris. The children set off, not knowing where they were headed. After staying in U.G.I.F homes, they were eventually taken to Drancy. Léon and his brother Isidore were interned there on July 22, 1944 and then deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 abord Convoy 77. Léon was killed soon after he arrived in Auschwitz, at the age of 12. His official date of death is August 5, 1944.

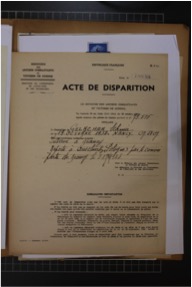

Disappearance certificate for Léon dated May 1955. A death certificate was issued later, in 1972, which includes the notation that he “died for France”.

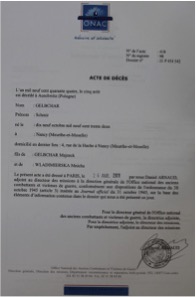

Leon’s death certificate, published by the ONAC, the French National office for veterans and victims of war, 2011

We had the opportunity to visit Auschwitz this year, where we were able to see for ourselves the vast destruction perpetrated by the Nazis. This memorial trip gave us a better understanding of what happened to Léon and the other deportees.

Remembrance is a duty, and something that we must pass on to future generations. This is what Ginette Kolinka told us during our meeting with her, when she explained how important it was for her that we become ” remembrance workers “. To this end, as a continuation of our biography work, we decided to initiate the process of erecting a plaque bearing the names of the forgotten people who spent time in the Poitiers camp. Although we live in Poitiers, we’d never heard of this camp before, either in school or as part of our local heritage. This is a great pity, as this “forgotten part of history” led to thousands of people being deported. As Félicia Barbanel Combaud herself pointed out in her testimony: “How many people don’t even know about this camp on the Limoges road in Poitiers?”.

To combat this neglect, we are keen to study the problem and hope to highlight it by means of a plaque bearing all the victims’ names. This is part of our history, and should not be overlooked. However, given that the idea of a plaque bearing the names of all the people who were interned in the camp is a quite ambitious and difficult to implement, we have also requested that the town hall affix a memorial tablet bearing Léon’s name at the address where he lived in Poitiers, so that passers-by can reflect on his life, and perhaps some of them will go on to find out more about him in this biography. This second step is well under way!

To end this biography with a tribute, since unfortunately we were unable to find any photos of Léon, Prudence drew a picture so that we could end this piece with a visual representation that will live long in our memories.

A drawing by Prudence, in memory of Léon

References

[1] SANSAL Boualem Le village de l’Allemand ou le journal des frères Schiller (The German village or the Schiller brothers’ diary), 2008, published by Gallimard (198 p)

[2] Léon Schmir Gelbchar’s birth certificate.

[3] Srojzeck Gelbchar and Mincha Wladiminska’s marriage certificate.

[4]https://entretiens.ina.fr/memoires-de-la-shoah/Barbanel/felicia-barbanel-combaud

Ina – Grands entretiens – Felicia Barbanel-Combaud dans la collection « Mémoires de la Shoah ». (25 Janvier 2010)

[5] LÉVY Paul, Un camp de concentration français Poitiers (1939-1945) (A French concentration camp in Poitiers, 1939-1945), 1995, published by Sedes (we drew on chapters 4, 5, 9 and 8 of this book to help compile our biography of Léon.)

https://www.cairn.info/un-camp-de-concentration-francais–9782718192314.htm

[6]Article by Betty Kaluski-Saville, Les enfants de l’U.G.I.F. en région Parisienne (The U.G.I.F. children in the Paris area) based on a lecture by Jean Laloum, Thursday, April 10, 1997. Les Enfants Cachés (the Hidden Children), Bulletin n° 19, June 1997, p 3.

[7] Chapter 9 of the book by Paul Levy

Sources:

- Records scanned and provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit organization (25 documents from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen and 10 microfilm records microfilms from the YIVO Institute for Jewish research)

- Records from the Vienne departmental archives, more specifically those on the Poitiers internment camp, reference 109 W. Léon GELBSCHAR’s name is listed in 109 W 311 and 109 W 314.

The Shoah Memorial website

- Paul Lévy’s Un camp de concentration français Poitiers (1939-1945) (A French concentration camp in Poitiers), 1995, published by Sedes. This historian has done invaluable research on the Poitiers camp, and has compiled numerous lists and explanatory tables from the archives. Léon appears several times in his work.

- Extract from Marie-Joseph Bopp’s, L’Alsace sous l’occupation allemande: 1940-1945 (Alsace under the German Occupation: 1940 – 1945), published by Xavier Mappus , 1945

- Article by Betty Kaluski-Saville, Les enfants de l’U.G.I.F. en région Parisienne (The U.G.I.F. children in the Paris area) based on a lecture by Jean Laloum, Thursday, April 10, 1997. Les Enfants Cachés (the Hidden Children), Bulletin n° 19, June 1997, p 3.

- Félicia Barbenel-Combaud’s testimony on the Mémoires de la Shoah (Memories of the Holocaust) section of the The French National Audio Institute website, Ina – Grands entretiens – Felicia Barbanel-Combaud (January 25, 2010)

- Sophie Nahum’s YouTube channel, Les Derniers (short testimonials by Esther Senot and Elie Wiesel)

- The biography of Isidore Gelbchar : written by a class of 9th graders at Fernand-Léger secondary school in Vierzon,in the Cher department of France, as part of the Convoi 77 project.

Read also : Consult the biography of Bernard BERKOWICZ

Français

Français Polski

Polski