Rebecca STEPANSKI

Photo of Rebecca Stepanski. Source: the Yad Vashem database of Shoah victims’ names

Birth and family background

Rebecca Stepanski née Franz, who was also known as Rivka, was born on September 11, 1909, at 25 rue de la Forge Royale, in the 11th district of Paris. She married Henri Stepanski, who was also born in Paris, on April 7, 1932.

Their marriage certificate provides some information about their parents. Henri Stepanski’s father was a tailor and was living with his wife, who was not working at the time, at 82 rue Championnet, while Mr. Franz, Rebecca’s father, was a butcher. He was also living with this wife, who also was not working at the time, at 25 rue de la Forge Royale. Both of Rebecca’s parents were born in Russia and had become French citizens in the mid-1920s.

The whole family was thus rooted in the heart of the French capital city, and endured all the effects of the war, from the hardships of daily life during the Occupation to persecution because they were Jewish.

Rebecca’s husband, Henri was an ex-serviceman and a dentist. They had two children: Jeanine, who was born on February 4, 1933, and Daniel, born on January 7, 1937. Henri was arrested in December 1941, during what came to be known as the “the roundup of the notables”, interned at Compiègne and deported on Convoy no. 1 on March 27, 1942, to Auschwitz, where he died on April 1. Rebecca then lived alone with her two children for almost three years, with no news of her husband. Daniel and Jeanine both went to school, the younger in “year 10”, at the Janson de Sailly school (1943-1944), the elder at the Molière school.

Henri Stepanski,

Source: the Yad Vashem database of Shoah victims’ names.

Arrest and deportation

Like a number of other Jewish families in Paris, Rebecca and her children lived through the war years before they too were caught up in the Nazi authorities’ genocidal process. On July 14, 1944, the Gestapo arrested the mother and both children at their home at 60 rue de la Faisanderie.

Photographs of the building at 60 rue de la Faisanderie, where the Stepanski family lived., Paris

Photos by Anne-Marie Poutiers.

The janitor’s testimony confirms that the arrest was carried out by the German political police, a repressive organization that focused on tracking down Jews from 1942 onwards. Rebecca’s sister, Simone Cumet, also confirmed the reason for the arrest, referring to the fact that the family was Jewish when, after the war, she applied to have Rebecca and the children legally registered as “non-returned persons”.

The arrest came at a time when the Normandy landings had already taken place and the Allies were advancing towards Paris. When Rebecca arrived at Drancy, the camp authorities confiscated 1004 francs, for which a receipt was issued on July 19, 1944. She was assigned internment number 25255. On the information sheet filled in when she arrived, the letter B can be seen: this meant that Rebecca, and by extension her children, were subject to immediate deportation.

What was Rebecca’s stay in Drancy like? There is little information available about this, but she wrote a letter, signing her name Renée Stepanski, to her friend Dr. Encausse on July 30, 1944, to thank him for his help.

“We’re going far away tomorrow morning. I’m not leaving in despair. I hope that we will soon be back and that we will see each other again”. The people who were interned in camps were given no information at all, as these few words from Rebecca testify, and before the horror of being deported, they kept their hopes alive. Rebecca was preoccupied with a series of questions: where were they going, what were they going to do there, when would they be back? Her questions went unanswered.

She also mentioned her husband, Henri, hoping that she would see him again and “rebuild a home”. She was therefore unaware, when she was deported, that she was in fact already a widow, and shows how little, if any, information spread outside the camps.

The convoy left Drancy on July 31, 1944 and arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944.

When they arrived at Auschwitz, the deportees were sorted into two groups: this is known as “the selection”. This selection was carried out inside the killing center, as the prisoners already in the camp had recently been made to extend the railroad line. Its purpose was to separate the healthy people who were fit to work for Germany from those who were not. The healthiest and strongest people were sent to do forced labor, while the weaker and less able people, such as children, mothers and seniors, were immediately killed in the gas chambers. Since Rebecca had her children with her, she was sent to her death as soon as she arrived. She was later officially declared to have died on August 05, 1944, as were her children. They were 34, 11 and 7 years old.

In various official post-war documents, Rebecca was declared to have died in Drancy, rather than Auschwitz. However, in 2003, a correction was made in Rebecca’s case, confirming that she died in the Auschwitz killing center on August 5, 1944, on the grounds that she was Jewish.

Maurice Stepanski, her husband’s brother, submitted a testimonial to Yad Vashem confirming that Rebecca Stepanski died in the Holocaust, and thus she was officially recognized as a Shoah victim.

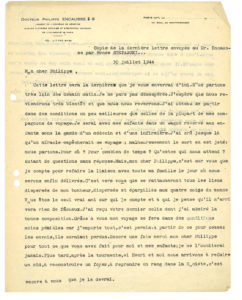

Rebecca Stepanski’s last letter to Dr. Encausse, sent from Drancy on July 30, 1944.

The letter reads:

Copy of the last letter sent to Dr. Encausse by Renée Stepanski

July 30, 1944

My dear Philippe,

This will be the last letter I send you from here. We’re going far away tomorrow morning. I’m not leaving in despair. I hope that we will soon be back and that we will see each other again. I shall be able travel in slightly better conditions than most of my fellow travelers. I will be with my children in a car specifically for children, under the care of a doctor and a nurse. Until now, I thought a miracle would prevent this journey but unfortunately the die has been cast: we are leaving. Where to? For how long? What lies ahead? So many unanswered questions. But, my dear Philippe, it’s you I’m counting on to get my family back together when we’re finally freed. It is to you that all the fragmented threads of my happiness, strewn and scattered to the four corners of the world, will return. You are the only true friend on whom I can count and to whom I believe nothing untoward will happen. I received your last parcel, which I found very well put together. Thanks to you, my trip will be less arduous, as I’m taking everything with me, which is allowed. From now on, please stop sending parcels, they will be wasted. Thank you once again, my dear Philippe, for everything you have done for me and my children; I will never forget it. Later, after all this turmoil, if Henri and I manage to rebuild a nest, a home and a place in society, I’ll owe it all to you.

In good times and bad, you and Suzanne will be my best friends. It’s to you, Philippe, that I also ask to notify my parents that I am leaving. If you see them, don’t forget to tell them that it’s not as bad as they think. We are in perfect health; we are leaving filled with courage and with great hope of returning soon. Who knows? Maybe I shall see Henri again sooner than I thought? If so, I cannot wait to leave. It’s not “goodbye” that I am saying to you, but “until we meet again” and see you soon.

I send you all warmest hugs and sincere affection.

Renée

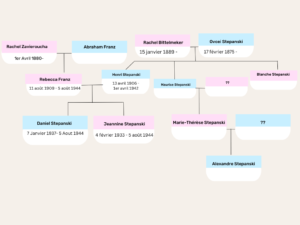

The Stepanski family tree.

Sources:

- Photographs of Rebecca and Henri Stepanski, the Yad Vashem database of Shoah Victims’ names.

- Photographs of 60, rue de la Faisanderie, Paris, taken by Anne-Marie Poutiers.

- File on Rebecca Stepanski, held at the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- File on Henri Stepanski, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Bibliography:

- Anne-Marie Poutiers and nine 9the grade students from classes 3e1, 3e2 and 3e3, Mémorial des enfants juifs du lycée Molière morts en déportation à Auschwitz (et de leurs familles), 1942-1944 (Memorial to the Jewish children from the Molière high school who died as a result of deportation to Auschwitz (and their families), 1942-1944), Salavre, published by Cleyriane, 2023.

Français

Français Polski

Polski