Sarah ISRAEl, née ABOUHA, 1899-1944

Hello,

We, the 2nd class of 9th grade students at the Blés d’Or junior high school in Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, became involved, together with our French and History teachers, in the Convoy 77 project. We chose to participate as part of our duty of remembrance and to pay tribute to three of the people who were deported on this convoy.

We used documents provided by the Convoy 77 association as sources for the biography, along with records from the civil registry office in Paris. We also gathered information from the archives of the Shoah Memorial website and the Yad Vashem website. Reading the Diary of Hélène Berr helped us a lot, as did the autobiographies of Ginette Kolinka, Henri Borlant, Simone Veil and Ida Grinspan. We also watched an interview with Marceline Loridan, “Ma vie balagan” (My chaotic life). During our research, we were lucky enough to encounter one of Simone’s nieces, Arielle Guempik, with whom we had a videoconference and who kindly provided us with some photos that she still had in her possession.

These various sources enabled us to learn more about the people we studied so that we could “bring them back to life” and not let them be forgotten.

My name was Sarah Israel and I was born on August 12, 1899 in Smyrna in the region of Aydin, in Turkey. My parents’ names were Mordehai Abouaph and Hanoula. My family had always lived in Turkey and we were Jewish.

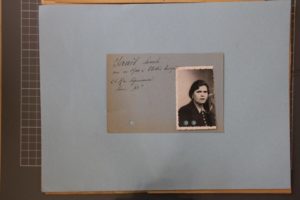

After the First World War and as a result of the endless Ottoman wars, I left everything behind. Many other people who had lost everything, as I did, decided to go to Europe. After the great fire in Smyrna in 1922 and the ensuing violence, my boyfriend David Israel, who was also born in Smyrna, and I decided to leave the country. Jews, together with Christians, were no longer welcome. We migrated to France in 1923 (see the document on the left). For me, France stood for democracy, freedom and human rights.

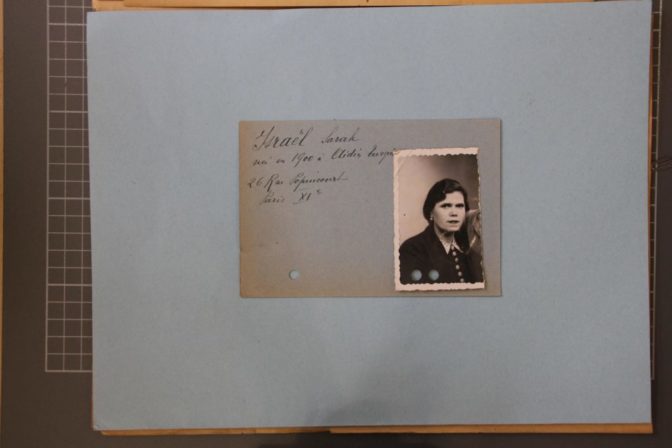

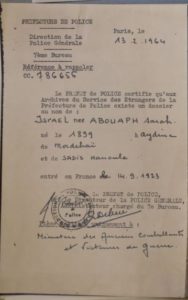

Despite the homesickness, I did everything I could to rebuild a new life, even a better life, for myself. We moved to Paris, to 7, passage Maurice and I found a job as a mechanic. I then fell pregnant and my first child was born on December 11, 1924 in Paris. We called him Salomon. David and I decided to get married, which we did on June 14, 1927 in Paris. From that day on, I became Mrs. Israel. Our second child was born on April 13, 1935 and we chose to give him a very French name, Marcel, because we felt well integrated in France. After we got married, I lived with my family at 26, rue au Popincourt in the 11th district of Paris. I then became a housewife after Salomon was born and my husband, who was a laborer, provided for all our needs.

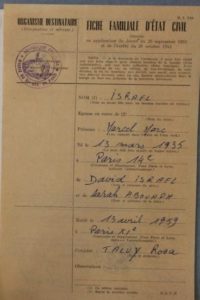

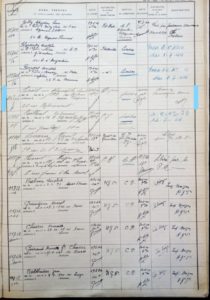

The 1936 census tells us that the Israel family was made up of the father David, the head of the family, who was a laborer, his wife Sarah and their sons, Solomon and Marcel. It also mentions their respective years of birth.

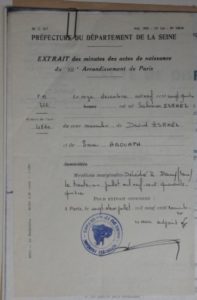

Salomon’s birth certificate

Marcel’s birth certificate

My life was quite peaceful before the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. We were frightened about the situation in Eastern Europe, however, because we knew what happened to the Jews there. Recently arrived neighbors from those areas told us about the violence, the fires and the persecution of the Jews, but for the time being, the situation in France was pretty good.

In 1940, France was defeated by Germany and thus had to sign the armistice, as called for by Marshal Pétain, the “hero of the First World War”, on June 17, 1940. France was divided in two: the zone occupied by the German army, in the North, and the rest of France, governed by Marshal Pétain. The Vichy regime was a political, anti-Semitic and conservative regime established on July 10, 1940, which lasted until August 20, 1944. Under the German occupation, life in France was plagued by shortages and widespread repression. According to a decree passed in October 1940 relating to the status of the Jews, they were forbidden to work in certain occupations. They could no longer be, for example, company directors, managers, editors of newspapers and magazines, managers of all businesses related to broadcasting, teachers or civil servants. The plundering of Jewish assets began with the compulsory Aryanization of businesses. In 1941, restrictions placed on Jews increased. They were forbidden to own radios, bicycles and birds, and there were limits on when they could go shopping.

Since the defeat, life became more and more difficult for the Jews. We had all sorts of ridiculous restrictions imposed on us, such as the ban on owning a bicycle, Solomon had to return his bicycle, and we also had to part with our radio. We could only go to the food shops at certain times and due to the shortages, we were rarely served politely. Everything was designed to make us disappear from everyday life. I couldn’t even take Marcel to play in the park anymore because parks were forbidden to dogs and Jews: who did they take us for? We were already heavily discriminated against even before the day in May 1942 when everyone over the age of six was required to wear a yellow star. The way people looked at us changed, some looked at us with contempt while others appeared pity us. In December 1942, everywhere in France, the Jews had to go to the police or the gendarmerie to have the word “Jewish” stamped on our identity cards and our food ration cards. We were no longer allowed outside our home between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. My circumstances and those of my Jewish friends became worse. Both mentally and physically, I had a very hard time of it. The more the weeks went by, the more the rules there were. Some hospitals even refused to admit Jewish people who were ill or in pain. I feared for my future and that of my children, especially since we heard more and more about roundups and even in our neighborhood, some people disappeared overnight.

I was arrested by the Gestapo at my home on June 29, 1944. My son, Salomon, had not come home from work the day before so I was already very worried and was expecting the worst. I was asked to pack a bag quickly and I took advantage of the opportunity to slip some cash into my belongings. Money always helped to soften some people up, as I had learned during my journey from Turkey to France. My husband had taken Marcel, who was 9, to the free zone to keep him safe. I would have liked Salomon not to be caught up in all this to avoid him suffering, but despite my pleas, they would not release him. Some Jewish neighbors were also arrested and we were all taken away on city buses.

Sarah arrived at the police station at 12.15pm on June 29 and left for Drancy at 2pm on June 30.

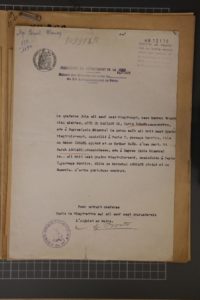

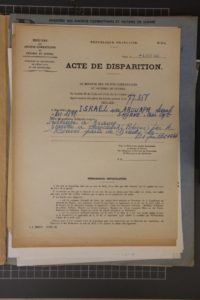

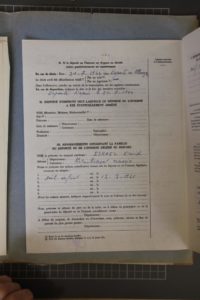

On the application submitted in order to have her civil status updated, we see that Sarah Israël was indeed arrested by the Gestapo and transferred to the Drancy internment camp because she was Jewish: a note says that she was “deported on racial grounds”.

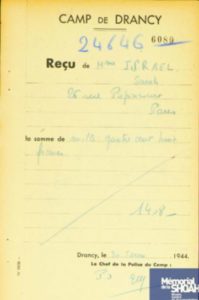

After a visit to the police station, I was interned on June 30, 1944 in Drancy camp, where I did not meet up with Salomon. I was registered under the number 24646.

The sum of money that was taken from Sarah on arrival in Drancy was quite significant at that time. Given her Turkish origins, she must have known that money was essential in the event of an arrest. Might she have been relatively wealthy?

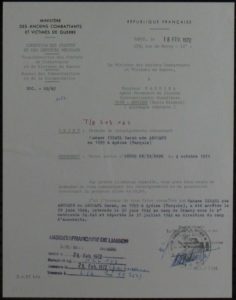

This document, issued by the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, shows Sarah Israël’s registration number. It also shows the different stages of her deportation, such as the dates when she was interned, arrested and sent to the Auschwitz camp.

On July 31, 1944, after a month in detention, I was taken by bus to the platform at Bobigny railroad station. We were then crammed into cattle cars, still not knowing our destination. Just the sight of those wagons told me what the Nazis thought of us. There were too many of us, so it was impossible to sit or lie down on the floor. The heat was unbearable and I was suffocating. I didn’t know if I would survive the trip in such conditions. Nothing was provided for our needs except a single bucket, which soon filled up and gave off an unbearable smell.

After several days of traveling, the train finally stopped and I felt a little relief to have reached our destination. As I got off the train, I almost fell over because my legs were so numb. We were hurried along by Germans shouting orders and dogs barking and the lights were blinding, but a man in a black and white striped outfit helped me to stand. I saw that there were hundreds or perhaps thousands of people on that platform, and wooden barracks as far as the eye could see. Some men began to load up the dead, and I realized that some of us had not survived the journey. A wave of nausea came over me because there was a distinctive, indescribable smell. Trucks were available for sick, elderly and tired people and for the children. These trucks resembled those of the Red Cross and, feeling tired and hungry, I got in. At that point, I thought that the Germans, in spite of their cruelty, still had a little humanity left in them.

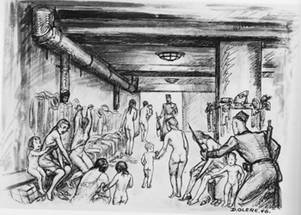

After a few minutes, the truck stopped and we arrived in front of a big building with tall chimneys. We were told we had to take a shower for hygiene reasons. We didn’t suspect anything was wrong until the SS told us to undress all together, and we obeyed their orders for fear of being punished and beaten. I then began to panic. I felt humiliated. There was no question of privacy, especially when it was the men’s turn to join us. What I didn’t yet know was that this shower was in fact a gas chamber and that when I entered, I had already signed my own death warrant. It was August 3, 1944.

These three drawings by David Olère, a deportee and Sonderkommando, illustrate Sarah’s fate: getting out of the cattle cars, the selection, the changing room for undressing and the exit from the gas chambers where the bodies were cremated.

This document, in German, tells us that Sarah died (gestorben) in Auschwitz in 1944 but there are no further details. She may have been taken directly to the gas chamber on the day of her arrival, around August 3, due to her age. She was 55 years old and must have been deemed unfit for work.

Her husband, David Israël, and her son, Marcel, the youngest, survived and they began researching information Sarah in order to trace what had happened to her: to have someone declared a “non-returnee” involved a long, bureaucratic process.

On May 2, 1946, the first step was to file an information sheet on which David stated his wife’s identity and her last known address. A witness, the hotel concierge, attested that the reason the Gestapo arrested her was because she was “israélite” (Jewish). David wrote in childish handwriting, which suggests that he did not have a very good command of written French.

On January 31, 1953, the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War confirmed that Sarah had been arrested, interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. With no further information to go on, her date of death was declared to be August 5, 1944, five days after the departure of the convoy. This was standard procedure for people under 14 and over 55 years of age. It took seven years for her death to be officially certified, and only then could the necessary steps be taken to have her recognized as a victim of war.

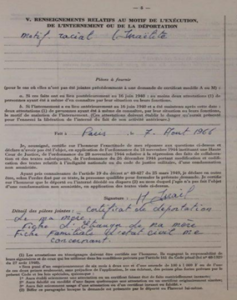

On August 7, 1966, Marcel, Sarah’s son, continued the process and found out that his father had remarried. He provided some documents in reply to a request for information in order to have his mother officially recognized as a victim of war.

On November 3, 1969, an assessment report approved her status as a “political deportee”, and later the same year she was awarded the title.

Marcel, clearly affected by his mother’s disappearance, continued his research in the hope of learning more. Unfortunately, in 1971 and 1972, the French Embassy to the Federal Republic of Germany could only confirm the absence of any archives relating to her presence in Auschwitz. Searches were made using both her married name and her maiden name, but nothing was found.

As part of our own research, we discovered a large family by the name of Abouaf, who lived in the same building in the same neighborhood in Paris (1926 census). We don’t know the exact link between the families, but most of them came from Smyrna, which leads us to suppose that some of the family could have come to France with David and Sarah, perhaps as a group, or perhaps the others joined them later.

We have chosen a wedding photo of some friends of the Abouaf family, which we found on the Shoah Memorial website, to remind us of the lives of these long-lost people, because weddings are a time of happiness, conviviality and hope.

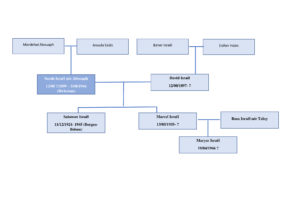

We have attempted to draw up a family tree, which is incomplete due to insufficient or inaccurate information (Marcel’s child shown as born in 1946, for example, whereas he was born in 1935)

The Israël family tree

Voir biographie de Salomon Israël

Dylan, Alexia, Maéva, Hilda, Marc et Louna.

Français

Français Polski

Polski