Salomon ISRAEL, 1924-1944

Hello,

We, the 2nd class of 9th grade students at the Blés d’Or junior high school in Bailly-Romainvilliers in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, became involved, together with our French and History teachers, in the Convoy 77 project. We chose to participate as part of our duty of remembrance and to pay tribute to three of the people who were deported on this convoy.

We chose to mix fictional autobiography and narrative to bring to life the three missing persons that we chose in class. First of all, the boys’ attention was drawn to Salomon Israël on the basis of his age, which was 17 when he was deported, because we felt an affinity with him. We discovered that he had been deported together with his mother, Sarah Israël, so we studied both mother and son. The girls chose to work on the biography of Simone Guempik for the same reason.

We used documents provided by the Convoy 77 association as sources for the biography, along with records from the civil registry office in Paris. We also gathered information from the archives of the Shoah Memorial website and the Yad Vashem website. Reading the Diary of Hélène Berr helped us a lot, as did the autobiographies of Ginette Kolinka, Henri Borlant, Simone Veil and Ida Grinspan. We also watched an interview with Marceline Loridan, “Ma vie balagan” (My chaotic life). During our research, we were lucky enough to encounter one of Simone’s nieces, Arielle Guempik, with whom we had a videoconference and who kindly provided us with some photos that she still had in her possession.

These various sources enabled us to learn more about the people we studied so that we could “bring them back to life” and not let them be forgotten.

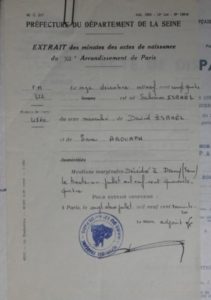

My name is Salomon Israël. I was born on December 11, 1924 in the twelfth district of Paris. I had a younger brother, Marcel, born March 13, 1935. My mother’s name was Sarah Abouaph and my father was called David Israël. They were both born in Smyrna, Turkey in 1899 and 1897 respectively. My parents left Turkey in the hope of a better life in France. They arrived in France on September 14, 1923, settled in Paris, at 7 passage Maurice, and got married in Paris on June 14, 1927.

As a young, Muslim country, Turkey was responsible for the Armenian genocide during the Great War of 1914-1918. It is likely that Jews were not welcome there either. In 1922, a great fire ravaged the Christian quarter of the city of Smyrna, at a time when massacres were already committed. This must surely have contributed to Salomon’s parents’ decision to leave. They went to Paris, where they got married in 1927 (see marriage certificate)

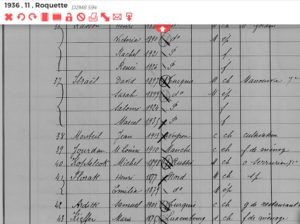

In 1939, at the start of the war, I was living with my parents and my brother in a very small flat at 26, rue Popincourt, a large apartment building which was home to many migrants and a large Jewish community, which was an advantage because it allowed us to help each other out and to better understand each other. My father was a laborer and my mother a housewife.

1936 census

26 rue Popincourt today

At the age of 15, I was already working to help out my parents. I worked in a store. From June 1940 onwards, I began to be afraid because, like many French people, I was stunned by the military defeat of France and I feared the arrival of the Germans. I was especially afraid of losing my freedoms, of not having much of a life anymore. I was stuck in the occupied zone because I did not have a pass to enter the free zone. I tried to remain optimistic because I thought that if I just followed the rules, nothing bad would happen to me.

Since the armistice of June 1940, which was signed on June 21 and 22 in Rethondes, France had divided into two: the northern zone was ruled by Germany and the free zone in the south was ruled by the Vichy regime, led by Marshal Pétain, who chose to collaborate with the Germans. The Vichy regime was established on July 10 when Pétain took control. This meant the end of the Third Republic and the birth of a new regime: “The French State” which was based on the motto “work, family, country” and which was a departure from the republican principles of “liberty, equality and fraternity”. Pétain was at the head of this dictatorship, and propaganda enabled him to promote his ideology. Freedoms began to be restricted little by little, the media were censored, political parties and unions were banned. From October 1940 onwards, Jews were excluded from French society by successive decrees concerning the status of Jews. The Vichy regime thus put France at the disposal of the Nazis and as a result it became complicit in the genocide of 6 million Jews. From May 14, 1941, the first round-ups were organized, overseen by the Paris Police Prefecture. At first, they only concerned Jewish men holding foreign citizenship.

In 1940, the Vichy regime’s restrictions were implemented throughout France. This began with the law of October 3, 1940, which excluded Jews from any position in the civil service, the press or the cinema. In October 1940, they were required to carry an identity card marked “Jew” or, for companies, “Jewish Business”. On June 2, 1941, the second decree on the status of Jews was enacted. Jews were excluded from independent, commercial, artisanal and industrial occupations. The list of prohibited jobs was then extended to include information services, publishing, entertainment, banking and insurance. On July 22, 1941, another law was passed, to allow Jewish assets to be confiscated and brought under the supervision of non-Jewish administrators. This task was entrusted to the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, or CGQJ (General Commissariat for Jewish Questions). Then, as from August 13, 1941, Jews were no longer allowed to own a radio. On February 7, 1942, a sixth German decree forbade them to leave their homes between 8:00 pm and 6:00 am. and then on May 29, 1942, it became compulsory for all Jews over the age of 6 to wear a yellow star. The rule took effect on June 7, 1942. On June 6, 1942, Jews were forbidden to work in the arts sector. As from June 7, 1942, they were obliged to ride only the last car in the Paris subway. On July 8, 1942, a ninth Nazi decree forbade Jews from going to certain public venues. They were also only allowed to shop in department stores, retail stores and artisanal workshops between 3pm and 4pm, when they were often closed. They were not allowed to walk in public squares or parks or even to use a telephone booth.

From October 1940 on, I noticed that many people I knew were losing their jobs. They were bewildered and did not know what to do. They could no longer feed their families. Signs started popping up on the shops saying “Jewish store” or, on the contrary, “under new management”. I felt as if I no longer belonged in my own neighborhood. I could only go shopping at certain times, I could no longer go to the movies, into a park or get into whichever subway car I wanted. We were no longer allowed to own a radio and I had to return my bike.

Starting in the spring of 1941, we could see that people in the neighborhood were disappearing one after the other, such as the baker on the corner of the street and the old lady who lived across the street from my apartment. The only thing they had in common was that they were both Jews. There was a lot of talk about arrests in our community. People just disappeared and we never heard from them again. I saw for myself a Jewish apartment being taken over by a French family. I had an idea that it would soon be my turn. The pressure was mounting with each passing day. My father decided to go to the free zone with my little brother because we were still Turkish citizens and he was afraid of being arrested and our family being taken at the same time.

As from 1942, I had to wear a yellow star sewn onto my clothes, and I felt like I was being watched all the time. People stared at me and sometimes pointed at me. Some people didn’t even speak to us, or they crossed the street when they saw us. I feel a sense of disgust on their faces, as if we were anything but equal human beings. One hour a day was not long enough for me to do the shopping because there were so many shortages, food was rationed and there were long queues outside the shops. We were deprived of all our rights. I was very afraid about what might happen next.

On June 30, 1944, on my way home from work, I was arrested in the street during a round-up. A large group of us was put on a bus and taken to the police station where I was booked in at 2am. I was questioned about my family and I decided to lie and say that I lived alone. At 2pm the following day, I was put on a bus heading for Drancy camp. It was not a very long journey. When I arrived in Drancy, I was sent to a men’s dormitory. I think the women and children slept together in another dormitory.

The Drancy housing estate, designed in 1932, was still unfinished when the war began. It was then used as an assembly and transit camp as part of the effort to deport all of the Jews in France, and as such it played a major role in the anti-Jewish persecution perpetrated in France during the Second World War. The conditions in the camp were atrocious. People went hungry and hygiene conditions were catastrophic. Sick people were mixed in with the other internees. The rooms where thousands of men were locked in, night and day, became hotbeds of disease, even when running water was put in.

On August 17, the last convoy left Drancy. On August 22, when it was liberated, there were approximately 1,400 internees in the camp. As part of the mass deportation and extermination of the Jews from France, Drancy was the departure point for 63 of the 74 convoys, carried more than 63,000 Jews in total. Of the 330,000 Jews living in France before the war, 75,721, or about 23%, were deported. Of those, barely 2,500 survived.

The conditions in Drancy were appalling; it was unhygienic, there was no privacy and I immediately felt at rock bottom.

Three days went by and then on July 31, some French gendarmes took us to Bobigny railroad station. When we got there, German soldiers pushed us roughly into dirty cattle cars, which did not inspire me with any confidence. We had been asked to take the bare minimum with us, a few provisions such as a little margarine and bread, but nothing substantial. We had no idea where we were going. Everything happened very quickly: we were notified the day before and taken away the next morning, which made me panic even more. There were lots of children and babies screaming and calling for help. I could see the fear on people’s faces; they were all in the same state as me.

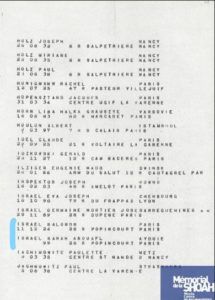

List of deportees on the convoy

There were between 60 and 80 of us in the cattle car, so there was not much room. We were all squashed together. The heat was stifling and it was very hard to breathe.

There was only straw on the floor and was not comfortable by any means. Many people were in despair when the doors were closed and locked and the journey began. There was only waste bucket, which soon filled up and the smell was unbearable. The first night was horrible because we had to stay standing, as there were too many of us to be able to sit or lie down. We were hungry and thirsty because we had soon exhausted our meagre provisions. All those who were strong enough tried to get closer to the skylight to get some air, but it was blocked by barbed wire. Some people took the opportunity to throw messages out onto the tracks.

The train was moving quite slowly and some of my companions managed to hoist themselves up to the little opening at the top car and look out. They saw the name of a station: Metz. That meant we were heading east.

On the second day, in the morning, several people were found dead on the floor. It was awful. People were screaming and going crazy at the sight of death. The hours that followed were so horrible that all we could do was look forward to the end of this terrible journey.

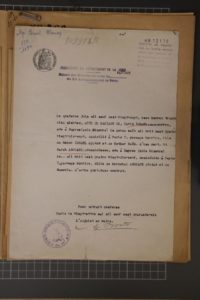

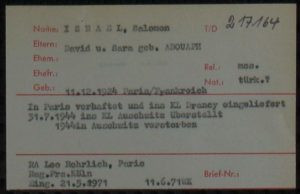

Several documents show that Salomon was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. For example, we have a record sheet relating to an application by David, Salomon’s father, for regularization of his civil status. It mentions the date of his arrest (June 26, 1944), the date of his internment on June 30, 1944 and the date of his deportation to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944.

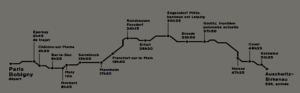

Yvette Lévy’s testimony tells us that Convoy 77 arrived in the early hours of the morning, before sunrise: we can therefore deduce from the map of the route that they left around midnight, which ties in with the fact that they tried to plan the departures when the railroad workers, who were becoming increasingly hostile, were not around. The fact that the journey took around 53 hours also shows that convoys of deportees were not considered to be a priority on the railroads.

We have a copy of an application for the status of political deportee, made by Salomon’s father. It describes the circumstances of Salomon’s arrest during a Gestapo raid when he was on his way home from work. It also states that he died in Auschwitz but does not give a precise date. This document was signed by David, his father, on July 30, 1966.

The dates given for Salomon’s deportation are from July 31, 1944 to August 5, 1944.

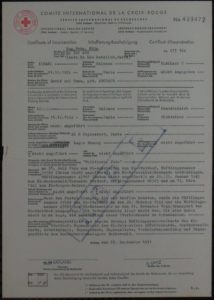

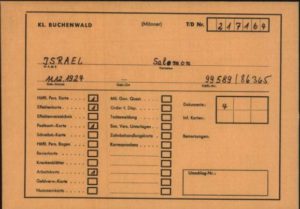

In 1953, the authorities closed his file with a question mark beside his date of death: July 31, 1944. To find out more about what happened to Salomon, the most important document is the reply to request for information sent to a Mr. Fassina, an international liaison officer, on February 18, 1972. This shows that Salomon had also spent time in other camps, such as Natzwiller, Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen. This is confirmed by a document from the Red Cross and by a record from the Documentation and Research Section, office 125. We even have his Buchenwald prisoner card.

After traveling for more than two days, I naively thought that the horror was well and truly over, but this was only the beginning. The big door of the cattle car opened slowly and the blinding light of the spotlights dazzled us. We could hear dogs barking and orders being shouted in German. I realized that we must have arrived at our destination, and it was not good news. Once the door was fully open, a Nazi officer ordered us to get out, which was an ordeal in itself for many people because it was a long way down to the platform. As we got off, men in striped uniforms asked us to leave our things on the platform and move along. I understood immediately that if I didn’t obey, I would be put to death. Blows were already raining down on people, so I followed the orders. When we got to the end of the ramp, after waiting a few minutes, we were separated into two lines. On one side were the able-bodied men and a few women, and on the other side were women, children and elderly people. Why did they want to separate us all? Why did they want to split us up like that? I was confused and did not know what was in store for me. I entered the camp with the group of men and we were taken to a hut where we had to undress. Naked, I felt humiliated and on top of that, we were shorn like animals. After passing through a disinfection area, I was given new clothes that did not fit me, and they tattooed a 5-digit number on my forearm. With that, I became 99589, a number that I had to memorize in German.

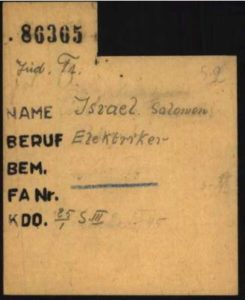

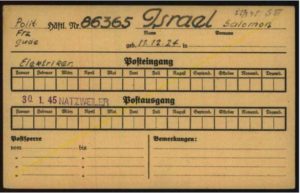

I only stayed in this camp for a few months, doing work that was intended to make us weak, such as breaking stones and digging drainage ditches. I was then transferred to the Natzwiller-Struthof camp in Alsace, where I became number 43101. There, I worked as an electrician, which gave me a bit of breathing space. I was transferred again on January 20, 1945 this time to Buchenwald, where I became number 86365. On January 25, I was transferred to a camp annexed to Buchenwald, the Ohrdruf camp, until January 30. I stayed there until March 1, when I was transferred for the umpteenth time to Bergen-Belsen. I was exhausted and had no strength left after 7 months of work, during which I was deprived of food and badly treated.

These cards confirm that Salomon worked as an electrician in Buchenwald. We have a similar card for the Natzwiller camp. The fact that he was transferred so many times shows how disorganized the Germans were when faced with the advance of the Allied troops. His transfer to Bergen-Belsen was the equivalent of a death sentence, since the camp, which was originally intended to hold sick people, had been abandoned by the Germans. They fled because typhoid fever was spreading throughout the camp and the Allies were close by. The camp was liberated by the British on April 15, 1945, but the prisoners were quarantined and, without medical treatment, many of them died. It was in this camp that Hélène Berr and Anne Franck died, at around the same time. Salomon probably also died there from sickness and exhaustion.

All that remains of Salomon and Sarah are their names on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris and the administrative documents attesting to their deaths and their status as political deportees. After the war, it was David, the father of the family, who began the research and administrative procedures to find out what happened to Sarah and Salomon. These documents show the lengths that he had to go to in order to have them recognized as victims of war, and they also prove that David Israël and his son Marcel survived. We know that David remarried and that Marcel married Rosa Taluy in 1959 in the 11th district of Paris. However, we also found that he had a daughter born on April 19, 1946 named Maryse Judith, which would have been impossible, given his age at the time. This demonstrates the limitations of archived records. Unfortunately, at this point, given the high number of homonyms, were unable to continue further with our research

Français

Français Polski

Polski