Albert CAMHI (1909 – 1985)

Photo: Shoah Memorial in Paris, Martine Camhi collection.

Albert was born on August 15, 1909 in Constantinople, then in the Ottoman Empire. His father, Vitali Camhi (or Kamhi), who was born in 1885, and his mother, Luna (known as Fanny), born in 1886, were married in the Zülfaris synagogue in Constantinople in 1908, and later emigrated to France. He had two younger siblings.

We do not know exactly when Albert and his family arrived in France, but given that his sister Dorette was born in 1911 in Istanbul and his brother Ely was born in 1913 in Lyon, in the Rhône department of France, we can assume that they arrived at some point between those dates, i.e. around 1912. Incidentally, Simone, the youngest sibling, was born in the 12th district of Paris in 1927. Albert was therefore raised and educated in France. He was naturalized as a French citizen on February 9, 1928, at the same time as his parents.

Albert went on to marry Esther Eskenazi, who was also born in Constantinople. Did they meet through mutual friends or family links, as was customary in the Turkish Jewish community?

When they married on September 16, 1933, in Bourg d’Oisans in the Isère department of France, where Esther and her were from, Albert was living at 173 rue Pierre-Corneille in Lyon. A marriage contract was filed with a notary by the name of Pelissier in Bourg-d’Oisans. At the time, Albert was described as an “employee”: he later became a travelling hosiery merchant.

When they were first married, Albert and Esther set up home in La Tronche, on the outskirts of Grenoble, also in the Isère department. Their son Victor was born at the Clinique des Alpes in Grenoble on September 6, 1934.

They were still living in Grenoble when they were arrested.

The Camhi family tree

THE WAR

After Hitler’s troops invaded Poland and France declared war on Germany, Albert, who was by then a French citizen, was drafted into the army. He fought valiantly and when France was defeated, he was demobilized and went home to his wife and son. A report from the French National Security Department dated 1962 stated that Albert, “despite his Jewish status”, had “had the right to continue his business as a hosiery merchant during the Occupation, thanks to his status as a veteran of the 1939-1940 war, when he was awarded the War Cross”. This was relevant because Marshal Pétain’s 2nd decree on the status of the Jews, dated June 2, 1941, prohibited French and foreign Jews from working in almost all professions.

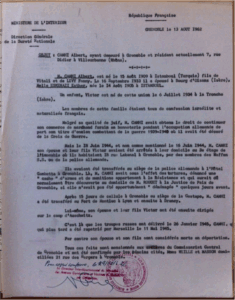

The French National Security Department’s report on Albert dated August 13, 1962. File on Victor Camhi, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-432-819-59

Albert later stated in a letter that his younger brother, Ely, had died in detention, i.e. as a prisoner of war, in 1941 or ’42, and would be awarded the distinction of “Died for France”, but this did not put an end to the persecution.

Albert almost certainly went to register himself as a Jew in a special census, as required under the Vichy government’s 1st and 2nd decrees on the Status of the Jews, which were then implemented by the Vichy authorites and the police. As of June 2, 1941, all Jews living in the “free” zone, in the southern half of the country, had to report to their local prefecture or town hall.

However, even after the Germans invaded the Vichy-ruled “free” zone in June 1942, the Jews living there were not required to wear the Jewish star. This made their day-to-day lives easier and, in Albert’s case, probably helped him carry out some not-so-legal activities.

ARREST AND DEPORTATION

On June 18, 1944, the Gestapo and the French militial arrested the entire Camhi family in their 4th-floor apartment at 18 rue Lakanal in Grenoble. This is according to Albert Camhi himself, who, on February 19, 1962, submitted an application to have his son officially acknowledged as having been deported. He had probably been denounced as a member of the French Resistance.

After he was arrested, Albert was taken to the Gestapo headquarters at the Hotel Gambetta on boulevard du Maréchal Pétain in Grenoble. There, he was tortured and forced to “report a cache of arms and ammunition belonging to the Resistance”. In the end, no such stockpile was found. A fortnight later, Albert was transferred to Lyon, where the notorious Klaus Barbie was in charge. He was first taken to Fort Montluc jail and then, on July 24, transferred by train to Drancy, along with Esther, Victor and a large number of other Jews from the Lyon area.

He only spent a few days in Drancy transit camp, northeast of Paris. On July 31, 1944, Albert, together with his wife and his son Victor, was deported on Convoy 77 from Bobigny station to the Auschwitz extermination camp. After a horrific journey with barely any food, water or ventilation, with the prisoners crammed into cattle cars 60 or so at a time, the convoy arrived in Auschwitz during the night of August 3-4, 1944. Convoy 77 was the last major transport to leave Paris before the Germans fled. At the time, almost two months after the D-Day landings, the Allied troops were closing in on the city.

When the train arrived in Auschwitz, Albert was selected to enter the camp to work. The men were lined up on one side, the women on the other, while seniors and people with children were herded onto trucks. It was then, during the selection process, that Albert saw his wife and son for the very last time.

After walking all the way to the Auschwitz camp and being tattooed the following day with the number B-3711, which from then on became his identity, Albert spent some time in quarantine. After that, he had to start work. He worked as a truck driver, which could be considered as a fairly “safe” job. His first name was listed as Vitali, while on another record from the Auschwitz camp, his surname is listed as Kahmi (both in fact his father’s names). Given that he was arrested as a Resistance member, rather than because he was Jewish, might the Resistance group in the camp have “helped him out”? Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing.

THE LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ

The Auschwitz camp had been all but deserted ever since the Nazis and the German army had forced the deportees who were well enough to set off on “death marches”. The Soviet army was approaching fast, and they wanted to move the prisoners to other camps. The Soviets eventually liberated Auschwitz on January 18, 1945. Albert was in the camp infirmary at the time, which is why he was not made to leave on foot in the snow with the others. With him were Alex Mayer, another Convoy 77 deportee, and Simon Stanger, who, like Albert, was arrested in Lyon and as also deported on Convoy 77.

However, the prisoners left behind in the infirmary were not returned to France immediately: the Soviets were not expecting to find anyone still alive in the camp so had no plan in place to take care of the survivors. After a long journey, Albert was eventually repatriated to Marseille on the south coast of France, on May 10, 1945. According to his daughter Martine, he weighed just 77 pounds (35kg) at the time.

THE RETURN TO FRANCE

When he was released, Albert said he was moving to 21 chemin des Bergers in Grenoble.

Once there, he began sending letters to ask for searches to be carried out for his wife and son. He completed a great deal of paperwork in the hope of finding Esther and Victor, who he hoped were still alive. On May 29, 1945, he sent his first letter to the Ministry of Veterans and Civilian Victims, saying he had heard that a train carrying 900 children had arrived in Paris. He wrote that he “still held out hope of finding them, despite everything he had seen and been through”. He was somewhat confused about the date on which they were deported, however. He wrote that they were arrested on June 6, 1944 (it was in fact June 18) and arrived in Upper Silesia on August 18, 1944 (rather than August 3-4, 1944).

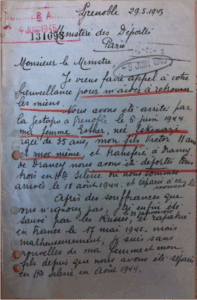

Albert’s letter to the Ministry of Veterans and Civilian Victims, dated May 29, 1945, . File on Victor Camhi, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-432-819-20

On June 13, 1945, Albert wrote a second letter to the Ministry, saying that a further trainload of returning deportees had just arrived in Paris and that he still had no news of his wife and son. This time he provided the correct dates for their arrest and deportation, and enclosed photos of them with his request. He pointed out that he was a French citizen who had “fought all through the war, and received commendations”, and that he had also lost his “younger brother who was in captivity in 1942”.

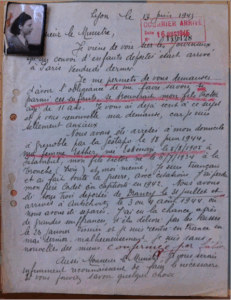

Albert’s letter to the Ministry of Veterans and Civilian Victims, dated June 13, 1945. File on Victor Camhi, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-432-819-14

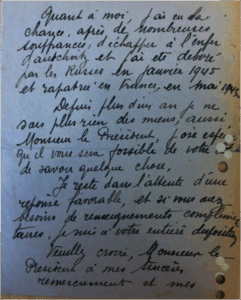

On August 2, he received a reply from the Office for Deportees and Internees that said “to our great regret, we have not yet been able to indentify any repatriated children who were deported on July 31, 1944”. Albert’s distress is palpable in all of his letters. On August 12, 1945, while he was staying with his parents at 173 rue Pierre-Corneille in Lyon, he even wrote a letter to the President of France, referring to “his many sufferings” and “the hell of Auschwitz” and asking for help in finding out what had happened to his family.

Albert’s letter to the Ministry of Veterans and Civilian Victims, dated August12, 1945. File on Victor Camhi, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-432-819-24

Albert eventually made a new life for himself with a woman called Régine Caridi, and they had two children together: Georges and Martine. In 1964, he was living at 7, rue Dedieu in Villeurbanne, a suburb of Lyon. He died in 1985.

Français

Français Polski

Polski