Albert PISANTI

In this biography, we would you like share with you the life story of one of the members of the Pisanti family, on which we and our class have been working. We are a group of five students: Gina, Elsa, Just-Patrick and Ambre.

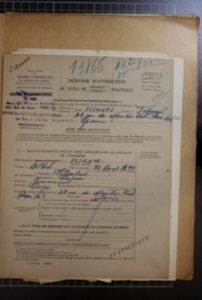

We decided to focus on the father of family, Albert Pisanti, who was deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. We chose him because we thought we would have more to say about him than about his daughters partly because he was older, and also because his story recounts the family’s past. We decided to write this biography in the form of a fictional autobiography in order to make his story more vibrant and to make him come alive through our text. We find it so very wrong that the Nazis cut short his life, which should never have ended as it did. We wanted to try to describe how he would have felt during this terrible ordeal. All the information included in this biography is based on archived material provided by the Convoy 77 nonprofit association, the books on the Holocaust that are listed at the end of the biography, several testimonies, including that of Albert’s daughter, Béqui Pisanti, which are also listed at the end of the text, along with our school trips to Drancy and Berlin.

BIOGRAPHY

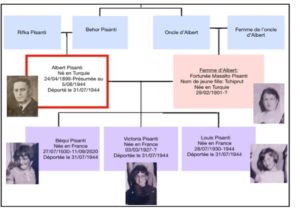

My name is Avram Pisanti (Albert in French). I was born on April 24, 1899 in Constantinople, which is now Istanbul, Turkey. I was the son of Rifka and Behor Pisanti and I was Jewish. I was born at a time when anti-Semitism was increasing in Turkey. As a result, when I was very young, I emigrated together with my family, as did many other Turkish Jews. We decided to move to France, which was a country renowned for its human rights. We thought we would be happy and free living there.

Albert Pisanti’s birth certificate

When I was growing up in France, I became close to my second cousin, my uncle’s daughter, Fortunée Tchiprut, who was born on February 29, 1901. She later became my wife and we had three daughters together.

Photo of the Pisanti family

Bequi Pisanti, the oldest girl, was born in Paris on December 30, 1925. After she was born, I married her mother, Fortunée, who would later become the mother of my other two children. Victoria, the middle one, was born on March 3, 1927 and Louise, the youngest, was born on July 28, 1930. My wife and I did not send our daughters to religious schools, but rather to public schools.

I lived with my family in an apartment that my wife and I bought when we were young, at 49, rue du Moulin Vert in the 14th district of Paris. I worked as an electrician and my wife was a seamstress.

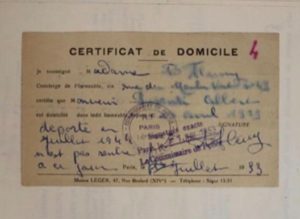

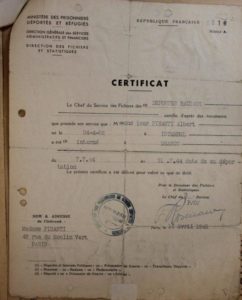

Albert Pisanti’s residence certificate

49 rue du Moulin Vert, Paris, France

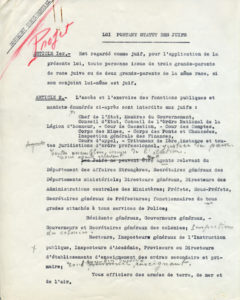

In the early 1930s, as was the case throughout Europe, the economic situation in France was precarious as a result of the stock market crash of 1929. In 1939, war was declared and obviously this worried us. On June 17, 1940, when Marshal Pétain asked for an armistice, we hoped that would be the end of it. However, from October 1940 onwards, when he first law concerning the status of the Jews came into force, things became ever more difficult for my family and I. Although I was not forbidden to work as an electrician, customers became increasingly scarce. Nevertheless, I managed to make some money with the help of my contacts.

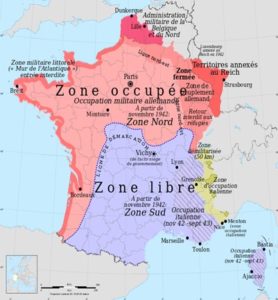

The law relating to the status of the Jews

In addition to that, my family and I were starting to really notice the anti-Semitism. We lived in a predominantly Catholic neighborhood. The janitor in our building knew we were Jewish. She had an anti-Semitic friend who could have turned us in, so she kindly advised us not to talk to the friend. When we travelled by bus, we were obliged to sit in the back. We felt a real sense of injustice and misunderstanding. We were being punished simply because we were Jewish. But more importantly than that, we were afraid. My wife and I feared for our daughters and for ourselves, especially since we lived in the Nazi-occupied zone. In 1941, the first round-ups targeted foreigners such as my wife and I. We were very fortunate that they did not find us. But these arrests made my wife and I even more anxious, because were both stateless persons. Unlike our children, who were born in France and were French citizens, we had kept our Turkish nationality, which meant that we did not have to wear the yellow star. This was compulsory for all Jews from 1942 onwards, but we had not had to take part in the census due to our nationality so we were not registered. My wife and I were quite indignant that our daughters should be branded with this distinctive symbol. But more than anything, we were afraid for them, that they would be victims of all this hatred against the Jews, or worse still, that they would be arrested.

On June 6, 1944, the Normandy landings took place. This was a source of real hope for my family and I. We finally felt sure that we had escaped arrest and no longer had to live in fear. However, I was arrested at work and interned in Drancy camp the following day, July 7, 1944. No one was expecting this, when we had thought only the day before that everything was finally over! A few days later, on July 12, it was my daughters’ turn. I was able to meet up with them in Drancy, but it was not much of a relief because we had no idea what would happen next. I was very worried about what would become of us. We had already heard about the convoys heading East.

Certificate confirming that Albert Pisanti was interned at Drancy from July 7 through 30, 1944, prior to being deported

The camp was made up of a number of tall buildings, each packed with internees like us, arranged in a U-shape with a large courtyard in the center where there were toilets for men and women as well as wash houses and offices for the guards. There was a guard post at the entrance to the camp. Even here, already, the living conditions were awful. We had little to eat and slept poorly. Our personal hygiene was terrible too: we only had a few shared sinks to wash ourselves, which meant that many internees got sick. The whole environment was unhealthy and uncomfortable, despite the few things left behind by previous prisoners. We were all crammed together because there were far too many internees. Fortunately, it was July, since had it been cold we would have had no means of keeping warm. Everyone was anxious: we were all afraid of being chosen to be sent to some unknown place. While we were in the camp, my wife often came to wave to me and our daughters from the café across the street from the camp. She paid the manager to allow her to stay longer beside the window. I was extremely moved by this gesture, but most of all I was afraid for her. She was taking a huge risk by doing this, she could have been arrested.

A model of Drancy camp

On July 31, 1944, it was our turn. I was a political deportee, and as such I was sent to the unknown destination that I had been dreading. In the morning, we were taken by bus from Drancy to the Bobigny railroad station. It was very hard for me to leave my wife, not knowing where my daughters and I would be taken, and not knowing how long it would be before we saw each other again. We then boarded the train, and spent three days and two nights in cattle cars bound for this unknown destination. I was worried, but we were nevertheless relieved that we were still all together. During those three days, we were treated very poorly. I, my daughters and the other deportees had no access to sanitary facilities. I was anxious, incredibly thirsty, and terrified of what was in store for my daughters and I at the end of the journey. All we had been told was that we were being taken someplace to work. However, I doubted this assertion because there were babies on the train. The cattle cars were full of silent people. I felt helpless, I could do nothing to help them or to rescue myself and my daughters from this nightmare.

The cattle cars in which the people were deported

When the train arrived in Birkenau on August 3, my daughters, the other Jews and I had all our personal belongings taken away. I was then separated from my daughters forever. They were taken away with some other women and I was ordered to join the men’s line. This was the worst ordeal of all for me. I was separated from all I had left in the world. They were heading towards an unknown destiny, and there was nothing I could do to help them. I even thought that this might be the last time I would see them.

After that, a guard sent me over to a group of older men. I felt the same anxiety as I had all along: “Where was I being taken and what was going to happen to me?”.

What actually happened was that Albert Pisanti was sent straight to the gas chambers, where he died in the same way as so many other people. Was it due to his age? At 45, was he really too old to work? Was it because there were already too many men working in the concentration camp? Unfortunately, we will never know the answers to these questions.

His body was then burned to ashes in a crematorium, so that there would be no trace of his ever having existed. His clothes and personal belongings were all collected by the sonderkommandos so that his legacy would be destroyed forever. This is why we are publishing this biography; to rewrite the story of this man whose life was so unjustly cut short and erased by the Nazis.

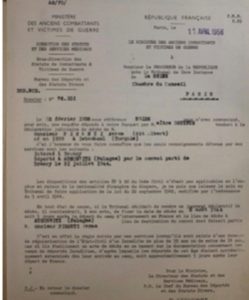

The document that determined the date on which Albert Pisanti died

Since there was no information about when Albert Pisanti died, it was taken to be August 5, 1944, as stipulated by French law: if the deportee was under 14 or over 55 years of age, he or she was deemed to have died five days after being deported, since such deportees were exterminated as soon as they arrived in the camps. This law should not really have applied to Albert Pisanti, who was only 45 years old, but there was no alternative.

When she returned to France home, his daughter Victoria searched for her father in the vain hope of finding him alive. She wanted to know if he had survived, and if not, to have him recognized as having died as a racial deportee and a victim of war. This also meant that she received an allowance granted to families of war victims.

Proof that Fortunée researched what had happened to her husband

The Pisanti family tree

Sources

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77.

- Witness statements from Béqui Pisanti, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, available on the Shoah Memorial website.

- Short biographies available on the Yad Vashem website.

- Books: Simone Veil – Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah; Ginette Kolinka – Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant – Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan – J’ai pas pleuré.

- Photos taken at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy

Français

Français Polski

Polski