Bequi PISANTI

During the 2021-2022 school year, two 9th grade classes from the Blés d’Or middle school in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, along with two teachers, Ms. Jorrion and Ms. Garillière, decided to participate in the Convoy 77 project.

This project aims to produce biographies of the people deported on the last convoy that left Bobigny station for Auschwitz.

We are Téa, Sara, Serena, Chloé and Louise, the five students who wrote this biography of Bequi Pisanti, a Jewish girl who was deported on Convoy 77.

We worked over many days and months to gather all the information about Bequi Pisanti through various archived records and her video testimony, which is available on the Shoah Memorial website.

BIOGRAPHY

My name is Bequi Covoidis. My maiden name was Pisanti. I was born on December 30, 1925 at 19 bis rue Chaligny, in the 12th district of Paris.

My father, Albert Pisanti, was born on April 24, 1899, and my mother, Fortunée, was born on February 29, 190. Both of them originally came from Istanbul, in Turkey, but they had to leave in the 1920s as a result of the Turkish War of Independence. They decided to move to France because it was a free country.

My parents set up home at 49 rue du Moulin Vert in the 14th district of Paris. My father was an electrician and my mother a seamstress. I had two sisters, Victoria, who was born on March 3, 1927, and Louise, who was born on July 28, 1930.

I had a normal, happy childhood. My sisters and I wanted for nothing. I spent my early years in elementary school. I remember it as a time when all that mattered was to play with my friends, to laugh and simply to be happy.

We assume that the three Pisanti girls would have gone to the Hippolyte Maindron Elementary School, which was quite close to their home at 49 Rue du Moulin Vert.

In 1939, when the Second World War began, I was only 14 years old. I was terrified by the thought of war.

In June 1940, Marshal Pétain’s government decided to collaborate with Hitler. I was surprised and frightened by this news. I was very afraid of what this collaboration might lead to. We knew that in Germany Jews were being arrested and confined in ghettos, separated from the rest of the population. Might the same thing happen in France? Would I still be with my family? And why the Jews? So many questions suddenly came into my head.

As of October 1940, new laws were introduced that restricted our activities and we were gradually excluded from society.

In 1942, we had to wear the yellow star to show that we were Jews. We were banned from public places such as parks and cinemas. We were only allowed to go to grocery stores at certain times. It was hard to take it all in. My parents didn’t have to wear the star because they were from Turkey and had their Turkish citizenship, but my sisters and I had to. To be almost banned from all social life just for being Jewish was horrible! I was 14 years old! We were children!

The yellow star was sewn onto our jackets. When we were out on the street, people would stare at us as if we were parasites. I didn’t like the way passers-by looked at me: it was a look full of disgust and malice.

I tried to hide this shameful symbol with my hair, or under my scarf. Luckily the stars were only on our jackets! When the weather was mild enough, I would take advantage of the opportunity to take off my jacket. I would also go to the park when the authorities weren’t around. But then the round-ups began. I feared for myself and my family. The janitor in our building was a great family friend, and she knew that we were Jewish. One of her friends was anti-Semitic, and the she was afraid that this friend would report us.

On April 1, 1943, when I turned 18, I finished school and got a job as a shorthand typist at the Desmé fashion house, at 9 rue d’Alexandrie in the 2nd district of Paris.

In 1944, one fine July day, my father was arrested at work. My mother, my sisters and I went to our aunt’s place in Villepinte. Someone knocked on the door: it was the police. I immediately realized what was happening. They asked my aunt for her papers and ours. As my aunt’s husband was a prisoner of war, she was not worried, but we were arrested because we were Jewish, even though we were born in France and my parents had applied for us to be naturalized as French citizens. My mother was at work at the time.

The police took my sisters and I to the detention center. We were put in a cell with some other children. We spend two days and three nights in that place, which was pretty scary. I was terrified, as were my sisters. What was going to happen to us?

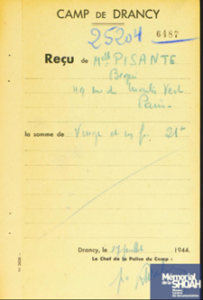

Then we were taken to the Drancy camp. It was made up of big four-story apartment blocks that formed a U shape around a courtyard, which felt really oppressive because we could not see beyond it.

When my mother found out where we were, she started going to a hotel across the street from the Drancy camp to try to catch a glimpse of us, and it was a relief to know that my mother wasn’t far away. Even though she couldn’t do anything to help us, she was taking the risk of being arrested.

On July 31, 1944, after a few days in Drancy, I was deported together with my father and my sisters. No one knew where we were going. The only thing we were told was to take warm clothes with us. A bus dropped us off at the Bobigny railroad station, where we were loaded into cattle cars in the evening. The train departed in the early hours of the morning. The trip lasted 2 days and 3 nights. On the train, we were all treated like animals: there were so many of us, crammed into the cars, each carrying a suitcase. We had just one container of water even though we were thirsty because it was so hot. There was one bucket in which we all had to relieve ourselves: the smell was nauseating. It was very humiliating; we had no privacy. Sometimes people would hold up a coat to hide the person who was relieving themself. The train stopped from time to time and someone would empty the bucket.

During the journey I heard from some other deportees that we were going to work in the east of Europe. From the moment we arrived in Auschwitz, the guards were brutal. A selection process was carried out to separate the men from the women, to decide if they were fit to work and to see if there were any small children who would be unnecessary mouths to feed. That’s when I was separated from my father and my sister Louise. I realized a few days later that she must have been killed soon after we arrived, on account of her age. As for my father, I kept hoping that he had been sent into the camp to work. We were all very afraid because we did not know which way we would be sent. Older people, small children, and people who were tired or injured were taken away in trucks that went straight to the gas chambers. On the other side, Jews who were deemed “fit” to work were taken into the camp.

The people who got into the trucks were taken to the gas chambers. When they got there, they all had to undress, they had to hand over their clothes, suitcases, jewelry and valuables. A few of them didn’t want to give up their belongings, so they hid them wherever they could.

Those of us who were able to work were taken to the showers to be disinfected, because the Nazis regarded the Jews as parasites. Then we were given some clothes, old and torn rags that were either too big or too small in some cases. We soon discovered that these clothes had belonged to people who had died.

It was a living hell: I was treated as a prisoner and was tattooed with a number: 19779. I worked in a commando unit where I was assigned to extracting oil in a weapons factory. It was not an easy task and it gave us spots on our skin. The rules of the camp were strict but at least I didn’t get beaten all day long. For washing, there was just a pipe with some holes in it to let the water out. I had to get used to the extremely cold water; I was not allowed to protest. Since we had no means of cleaning ourselves after going to the bathroom, I tore my underwear so I could wipe myself with it. The conditions in the camp were horrific: it was very cold. The air we breathed smelled of burning flesh from the camp crematorium. Some people worked even when they were sick to avoid being seen as weak and being sent to the gas chambers.

I was transferred to the Kratzau concentration camp in Poland at the end of October 1944. This camp was different from Birkenau, and stricter: here, it was a matter of survival. We counted the places in the line to get to the soup pot when it was nearly empty to be sure of getting the thickest soup. I remained in Kratzau until we were liberated on May 8, 1945. That day, we were surprised not to be woken up at dawn, and when we went outside there were no guards. We realized then that the Germans had deserted the camp and that we were free.

I was soon repatriated to France where a doctor prescribed a strict diet for two or three weeks because I had eaten so little, if anything, in the camps that my stomach had shrunk: I had to eat porridge and pureed food to give my intestines time to recover. I was hardly hungry anyway, because I had got used to not eating. I managed to tell my mother right away so that she would be there to welcome me when I arrived in Paris on May 24, 1945.

When I got back to Paris, I didn’t really keep in touch with my friends from the camps. I met a Greek Jewish man and married him on June 28, 1947. We had two daughters. After the war, I got my parents’ old apartment back and managed to resume a fairly normal life, going back to work in the same office as I had before the war. When my daughters were old enough, I told them my story. Then I began getting together with some other survivors once a year, in a restaurant.

In later life, Bequi gave testimonies in schools, but as she got older, she felt that was no longer up to it. She died on September 11, 2020. The Shoah Memorial has posted a tribute to Bequi Pisanti on its website.

Sources

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77.

- Witness statements from Béqui Pisanti, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, available on the Shoah Memorial website.

- Short biographies available on the Yad Vashem website.

- Books: Simone Veil – Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah; Ginette Kolinka – Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant – Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan – J’ai pas pleuré.

- Photos taken at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy.

Français

Français Polski

Polski