Berthe LIBERS

Berthe Libers – 1931 – Family archives

As their contribution to the Convoy 77 project, five 9th grade students from class 3e at the La Cerisaie middle school in Charenton-le-Pont, in the Val-de-Marne department of France, researched Berthe Libers’ fascinating life story and wrote her biography, while another group worked on the biography of her sister, Fanny. The project was overseen by their History and Geography teacher, Nathalie Baron.

The research was carried out using records provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, as well as others found over the course of the year. We were fortunate enough to make contact with Sophie de Juvigny, Berthe and Fanny Libers’ great-niece, who kindly shared some invaluable information and documentation relating to her aunts.

The first part of Berthe’s biography is similar to that of her sister Fanny, which is also featured on the Convoy 77 website.

This biography was written by Justine Camus–Caramelle, Maëliss Couteux, Aurore Dabrowksi Richard, Lina Duval and Emilie Lebrun, with the guidance of Nathalie Baron.

I – The Libers family: from Russia to Paris

Berthe’s father, Leib was born in Vladimir, near Moscow in Russia, on October 10, 1874. His parents, who came from a town called Loudsky, were Isaac, a carpenter, and Sarah Thanis, who did work. Her mother, Esther Fetz was born on June 1, 1881 in Równo (now Rivne in Ukraine, having previously been ruled by Russia and Poland). Esther’s father, Yakov, ran a store and also took care of one of the town’s synagogues and her mother, Socia, did not work. The family was Jewish.

Esther was the oldest of 4 or 5 children. She never went to school and spoke only Yiddish, a Germanic language spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. Her family must have been fairly poor, because she began working in a bakery when she was just 8 years old, delivering bread to customers each morning. When she grew up, Esther opened a little tea room opposite a large school in the Christian quarter of Równo.

Esther’s marriage to Leib would have been arranged by her father. The couple went on to have a daughter, who died shortly after she was born, and then another, Chiffra, who was born in Równo on December 25, 1903.

Leib emigrated to Paris first, on his own, in 1904. Esther and their daughter Chiffra joined him later. He probably left Russia to avoid the compulsory 7-year military service, which had been introduced at the start of the war between Russia and Japan, which lasted from February 8, 1904 to September 5, 1905. In addition, pogroms happened often in their area. These were attacks on the Jewish community, often including looting and murder.

Their marriage certificate, issued at the town hall in the 11th district of Paris on August 26, 1914, reveals that they were then living at 3 rue Keller in the Bastille neighborhood. It was not far from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which had long been Paris’s main furniture manufacturing and sales district.

Berthe was born in Paris on June 28, 1906, and her sister, Fanny on September 11, 1918.

Berthe’s birth certificate – Paris archives – 11N 329

In August 1914, Leib, who had been using the name Léon since he arrived in France, tried to join the French Foreign Legion, which had been made possible by a decree dated August 3, 1914. However, he was rejected because he was unable to find a uniform to fit him. However, his willingness to enlist meant that he and Esther were able to apply for French nationality, which was granted on September 4, 1926.

As a result, Berthe and Fanny also became French citizens, but Chiffra, because she was born in Russia, was ineligible and thus remained stateless.

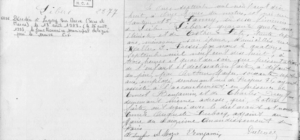

A page from the naturalization register – French National archives

According to memories passed down through the family, Léon was a strict father but at the same time very affectionate towards his daughters, who he wanted to raise in the best way possible.

He had learned the French language, was able to read the newspaper and was interested in politics. He was very grateful to France and the French people for making him welcome and enabling him to live freely, in a tolerant society.

Esther, on the other hand, found it harder to integrate, and felt isolated. She learned to speak French with her daughters, little by little, but never mastered reading and writing it.

She kept in touch with her father regularly, corresponding with him in Yiddish. Before the First World War began in 1914, she would take Chiffra and Berthe back to Równo during the summer recess. From 1911 to 1914, Esther’s brother Elie came to live with them in Paris, where he studied medicine.

Léon, Esther, Chiffra, Berthe and Fanny in the 1920s (Family archives)

A piece of furniture made by Léon (Family archives)

Having no doubt learned the trade from his father, Léon opened a cabinet-making workshop at 58 rue de Charonne. He produced fine furniture featuring marquetry made of exotic hardwoods and bronze. The family has preserved some of these pieces, including the chest of drawers in the photo above.

Léon’s sold his furniture cheaply and his wife did not work, so the family’s income was quite low. In October 1934, Léon, then aged 60, died of pneumonia at the Broussais hospital in Paris.

By that time, Chiffra, who went by the name of Sophie, had probably left home. She was still listed with family in the 1926 census under her married name, Krajcer, but was no longer there

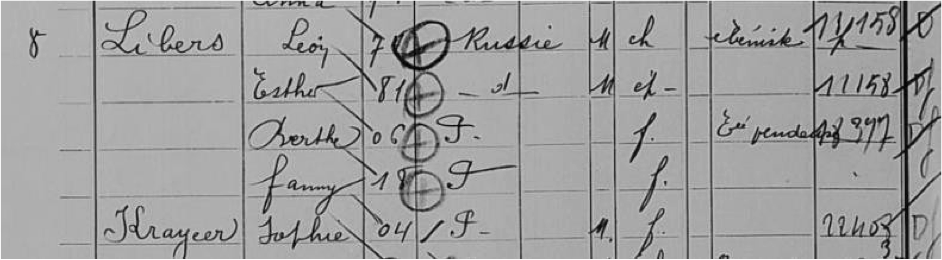

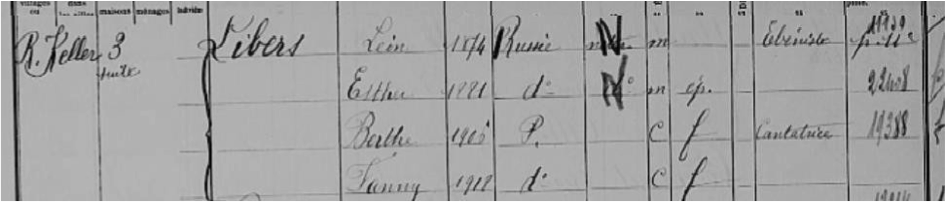

1926 census listing for 3 rue Keller – Paris archives

1931 census listing for 3 rue Keller – Paris archives

Sophie (Chiffra) married a man called Simon Krajcer and the couple had two daughters, Léa and Annette, who were born in Paris in 1927 and 1929. The family lived at 10 rue de Sévigné in the 4th district of Paris.

After the war, Sophie’s younger daughter, Annette, wrote a lot about her what had happened to her family. Her daughter, Sophie de Juvigny, kindly shared her stories with us. Annette Krajcer-Janin died on January 23, 2024 in Avignon, in the Vaucluse department of France.

Sophie Krajcer and her daughters, Annette and Léa

(Source: the Cercil-Musée Mémorial du Vel d’Hiv (Study and research center on the Loiret internment camps -Vel d’Hiv memorial museum) Facebook page)

II – Life before the war

Despite their financial difficulties, Léon and Esther were keen for their daughters to get a good education. For example, Berthe and her sisters took violin, piano and singing lessons. As regards schools, we were unable to find any records for Berthe, but we did discover that her sister Fanny went to school at 4 rue Keller, and also on rue Trousseau.

Berthe passed her middle school leaving certificate, which the most able students took at the age of 15. She then worked in her father’s workshop, where she handled some of the accounting and secretarial tasks, as well as customer liaison.

When her father died in October 1934, Berthe, who was 28 by then, continued to live with her mother and her sister Fanny at 3 rue Keller.

The apartment building at 3 rue Keller, in the 11th district of Paris (photo taken by Nathalie Baron)

Berthe then worked in a variety of jobs, including as a radio presenter at Radio-Cité in Paris, which broadcast from September 15, 1935 to June 14, 1940. Later, when she gave evidence at Xavier Vallat’s trial (see below), Berthe stated that she was “a journalist, unemployed during the war”.

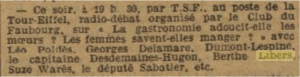

She also took part in debates on the radio, as can be seen in this announcement in the French newspaper “L’œuvre”, dated November 23, 1928:

(Source: Retronews)

Berthe had a good singing voice. Together with her sister Fanny, she was in the choir at the Tournelles synagogue on the famous Place des Vosges in Paris, led by choirmaster and Jewish music specialist Léon Algazi. It would seem, however, that they only went there to sing, rather than out of any religious conviction.

A number of newspaper articles reported that Berthe was a singer, and that she performed at the Grand Orient de France concert hall, at 16 rue Cadet in Paris. She is listed as a singer in both the 1931 and 1936 censuses. She may have been intending to make a career out of it.

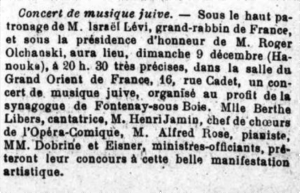

Article in L’univers israélite (Jewish world) dated November 23, 1928 (Source: Retronews)

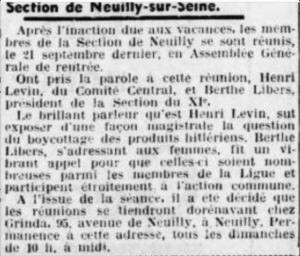

Berthe was also an active member of the International League against Anti-Semitism (L.I.C.A), which was founded in 1929 by the journalist Bernard Lacache, which in 1932 became the International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism.

This article, published in the L.I.C.A. newsletter Le Droit de vivre (The Right to Live) on September 1, 1933, says that Berthe was president of the L.I.C.A. branch in the 11th district of Paris, and was calling for on women to get involved (Source: Retronews)

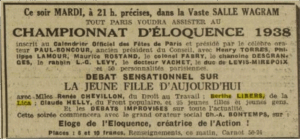

Berthe also took part in public speaking competitions, as reported in the left-wing paper, L’Œuvre, on June 14, 1938.

Announcement in “L’Œuvre”, dated June 14, 1938 (Source: Retronews)

Berthe’s wide-ranging interests reflected her eclectic, militant and determined nature, which was soon to be put to the test during the war.

III – Survival and resistance during the war

After Léon died, life was tough for Esther and her daughters, Berthe and Fanny.

The situation became even more difficult when the war began, as they faced shortages of both food and fuel for heating, which made them feel insecure. They also suffered the effects of the anti-Semitic laws that were progressively introduced in France, such as the requirement to wear a yellow star and to travel in the last car on the Paris subway.

During the Occupation, Berthe worked at a U.G.I.F. (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews) children’s home in Saint-Mandé, now in the Val-de-Marne department of France. The French government had founded the U.G.I.F. on November 29, 1941, supposedly to represent Jews in their dealings with the public authorities, particularly with regard to social welfare, contingency planning and social restructuring. It helped Jews still living freely in society and also those who were interned in the Drancy camp. All Jews were required to join the organization and pay a membership fee. Many of the U.G.I.F. managers were French Jews, who believed this meant they would be safe, but most of them ended up being deported as the war progressed. Some staff members were also active members of the Resistance, and succeeded in saving a few children’s lives.

After the war, on December 9, 1947, Berthe testified at Xavier Vallat’s trial. Vallat was a staunch Catholic and a militant anti-Masonic and anti-Semitic activist and parliamentarian. From 1941 to 1942, he was the Vichy government’s General Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, and as such was responsible for bringing in the legislation that founded the U.G.I.F. He was tried before the High Court of Justice, found guilty of indignité nationale (national unworthiness), and sentenced to ten years in prison and degredation nationale (national demotion) for life. This entailed: the loss of the right to vote; exclusion from elected office and public or semi-public positions; dishonorable discharge from the military and loss of all decorations; exclusion from management positions in businesses, banks, the press, and broadcasting; exclusion from all positions in trade unions, professional organizations, the judiciary, education, journalism, and the Institute of France; the loss of the right to keep and bear arms.

During her testimony, Berthe stated that she was 42 years old, worked in the “furniture delivery” business and lived at 3 rue Keller.

She stated she had applied to the U.G.I.F. in May 1942, thinking that if she was involved in their social work, she might be able to “help alleviate human misery”.

She went on to say that there was no work for her at the time, but she was called back in on July 15, 1942. The following day she and some other people were asked to make “labels with a short piece of string”, unaware that they would be used during the Vel d’Hiv roundup, during which her sister Sophie and her daughters were arrested. They were interned in the Pithiviers camp, and Sophie was then deported on Convoy No. 14 on August 3, 1942, bound for the Auschwitz camp, from which she never returned.

Annette’s later wrote in her book Le Dernier Été des Enfants à l’Etoile (The Last Summer of the Children with the Stars), that on August 15, 1942, she and Léa were transferred to Drancy internment camp, where a cousin who worked there managed to have their names removed from the deportation list. Berthe, who by then was a U.G.I.F. social worker, had sent the Nazi authorities a list of 36 children who were eligible for release, including her two nieces, who left the camp on September 23, 1942 and were then placed with foster families and kept hidden. After the war, they were reunited with their father Simon, who, in late 1941, had been assigned to a foreign workers’ group in the Ardennes region of France.

The U.G.I.F. also assigned Berthe the task of “going to fetch Jewish children who were some distance away, in the suburbs or in the country”. She was to go to private homes and bring children back to the Lamarck center. This was supposedly “to keep them safe”, but in reality, they were to be sent to Drancy and then deported but Berthe, who realized this, managed not to actually do it, thereby saving the children’s lives. For this purpose, she was provided with the necessary passes, which among other things, she kept as evidence.

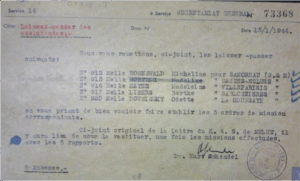

One of the passes that allowed Berthe to travel to collect the children – Shoah Memorial, Paris

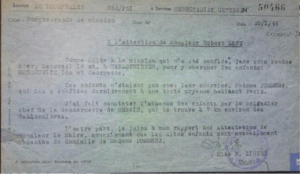

One of the reports that Berthe wrote about an assignment, dated January 30, 1944 – Shoah Memorial

In a letter dated July 7, 1950, Berthe stated that from January 1, 1944 to May 9, 1945 she had been actively involved in the Plutus Resistance network as a 3rd class assignment coordinator.

The Plutus network, which was based at 151 rue du Temple in the 3rd district of Paris, was set up to provide false identity papers to Jewish children and adults and smuggle them across the demarcation line into the Free Zone.

Pierre Kahn-Farelle was in charge of producing the fake documents. After the war, he signed a witness statement confirming that Berthe had been a member of the Resistance, responsible for arranging for Jewish children to be smuggled out of the country.

Roland Haas’s book “Journal de déportation” (Deportation Diary) provides more details about the Plutus network. It was made up of “64 permanent and 80 ad hoc agents, a stock of 18,000 rubber stamps, over 100,000 blank forms and a monthly output of 1,500 complete sets of identity papers”.

Part of one of Berthe’s letters, dated April 9, 1954 – French Defense Historical service

Berthe thus provided false papers, work permits, birth certificates and food ration cards to Jews who were living in hiding in Paris.

These documents were supplied by Colette Heilbronner, née Levy, alias Claudine, one of Berthe’s friends from the L.I.C.A., who also belonged to the Plutus network.

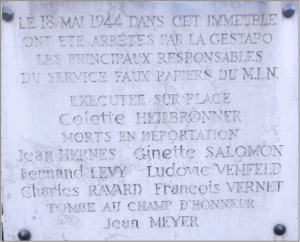

The French website maitron.fr, which describes itself as “a biographical dictionary of the workers’ movement”, says of her: “Colette Heilbronner moved to Paris after her husband was arrested. She continued the fight, working in a clandestine MLN workshop in Paris, at 25 Cité des Fleurs in the 17th district. The Germans discovered the workshop on May 18, 1944. She was shot dead on the spot.”. Some other members of the network were arrested on the same day and were later deported and died.

The memorial plaque at 25 Cité des Fleurs (photo by Emilie Lebrun)

IV – Arrest and deportation

Berthe and her sister Fanny were arrested at their home at 3 rue Keller following the search and arrests carried out on May 18, 1944 at Cité des Fleurs. We suppose that the Gestapo must have found an address book containing Berthe’s contact details, unless someone had reported her at around the same time.

After the war, Berthe engaged in extensive correspondence with various government departments, including the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs. In one of her letters, she wrote: “I was arrested on June 17, 1944, taken to Rue des Saussaies by the Gestapo, where I was interrogated and tortured”.

Berthe and Fanny were taken to the Gestapo headquarters at 11 rue des Saussaies in the 8th district of Paris, and then sent to the German-run prison at Fresnes.

From there, they were transferred to the Drancy internment camp on July 10, 1944 where they were incarcerated on the third floor on staircase 3.

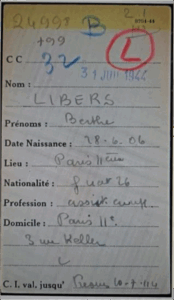

Drancy camp records – Shoah Memorial, Paris

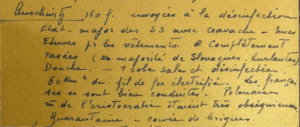

On July 31, 1944, Berthe and Fanny were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. According to Berthe’s deportation summary dated June 4, 1945, they traveled in a cattle car with some 60 other deportees, including 18 elderly people and a large number of children.

Convoy 77 arrived at the ramp in Birkenau on August 3, in the early hours of the morning, where SS men, guns drawn and dogs baying, made everyone get off the train. During the journey, some of the prisoners had died, and their bodies were still lying in the cattle cars. The SS then carried out the selection process, together with the infamous Dr. Mengele, and decided who would be sent to the gas chambers (children, women with children, elderly and sick people), and who would be sent into the camp to carry out forced labor.

During the selection, the sisters were separated from each other. In the end, however, the SS man sent them both to the group chosen to work in the concentration camp. They then walked alongside the barbed wire to the camp, where they were put in filthy barracks.

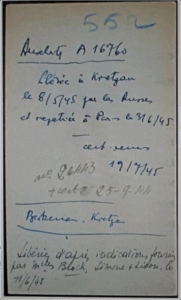

The day after she arrived in Auschwitz, Berthe was tattooed with the number A 16760, and told that this was now her identity. A prisoner used a needle and ink to etch an indelible number on all the newly-arrived prisoner’s forearms.

Berthe and Fanny, like all the other deportees, had to endure frequent roll calls, constant abuse, insufficient food and poor sanitary facilities. We do not know exactly what type of work they did, other than the “brick tasks” that Berthe described in her report about the deportation soon after she returned to Paris.

On October 29, the two sisters were transferred from Auschwitz to the Kratzau camp in Czechoslovakia. The Weißkirchen bei Kratzau kommando was in the Sudetenland region of northern Czechoslovakia, some 10 miles from Reichenberg. It held more than a thousand women, of various nationalities and origins, most of whom worked in a munitions factory.

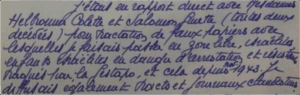

Extract from Berthe’s report on her deportation, dated June 18, 1945 (French National archives)

According to her niece, Annette, Berthe was suffering from a leg infection and was unable to work. She was therefore sent to the camp infirmary, where a female Jewish doctor kept her hidden during the selections.

Fanny, who worked in the factory, later testified that she went to see Berthe every evening to cheer her up. She sometimes picked dandelion leaves on her way back from work to give Berthe a little extra nourishment.

Berthe is also mentioned in Léa Raulet’s biography. She was in the infirmary when Lea was admitted to give birth to her daughter, Danielle Dadoun. Our teacher spoke with Danielle, whose videotaped testimony is available on the Shoah Memorial website. Here is some of what she said:

“In Kratzau, Léa worked in a factory with the other deported women. (…) Back at the camp, Léa was taken to the infirmary. Another prisoner, Berthe Libers (who, like Léa, had been deported from France on Convoy 77), told her that “it’s the little feet that are pushing.”

She also recalled that, as a child, her mother took her to see Berthe Libers, a fellow deportee who was there when she was born. Ms. Libers wrote a poem about the children deported on Convoy 77, and sent Léa a signed copy. Danielle went on:

“She put in a little note for her, saying she was a wonderful mother.”

After the Soviet army liberated the camp on May 9, 1945, Berthe was taken by ambulance to a local hospital, where she stayed for two weeks before being returned home to France. The nuns at the hospital also took in Fanny. The two sisters then travelled back to France by train with some prisoners of war. Berthe, who was very weak and still unable to walk, was carried on a stretcher or pushed in a wheelchair.

On June 2, 1945, the two sisters arrived at the Lutetia Hotel on boulevard Raspail in Paris, which, since April 26, 1945, had been used as a reception center for many of the Nazi concentration camp survivors when they first arrived back in France. Before that, the Germans had used it as the headquarters of the Abwehr, their intelligence and counter-espionage service, and the secret police, and it was from there that they ran their anti-Resistance campaign.

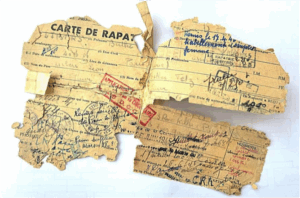

Berthe’s repatriation card (family archives)

V – Berthe’s life after the war

Sophie de Juvigny told us a little about her aunt Berthe’s life after the war, some of which comes from notes made by her mother, Annette.

Soon after they returned to France, Berthe and Fanny set off to 3 rue Keller, still not knowing what had become of their mother. It turned out that Esther was living at 10 rue de Sévigné in their sister Sophie’s old apartment. They and their mother then moved back to 3 rue Keller, where they also took in their nieces, Annette and Léa, until their father, Simon, came to collect them around a year later.

Esther died of viral hepatitis in 1958, at the Saint-Antoine hospital in Paris.

Berthe also spent some time in a convalescent home in Nice, on the south coast of France, after which she stayed there and met a man called Fernand, and shared his life for fifteen years. She also remained close to her niece, Léa, who lived in the nearby Var department.

During her time in Nice, she became involved in the Fédération Nationale des Déportés, Internes, Résistants et Patriotes (National Federation of Deportees, Interns, Resistance Fighters and Patriots) and, according to a 1975 article in the Patriote résistant, which has been passed down through the family, took part in a remembrance event at what was later to become the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

Her post-war letters bear the addresses 20 rue Amiral de Grasse and 53 rue de la Buffa, both in Nice.

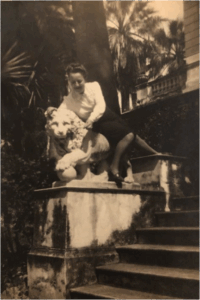

Photo 1: Berthe in Nice in 1946 – The inscription on the back reads “with my unfailing love – auntie Bête, April 1946” (Family archives)

Photo 2: Berthe in Nice in 1948 – “To my dear nieces with my deepest affection – Nov. ’48, Berthe” (Family archives)

From her letters, we gather that Berthe was a strong, spirited woman. She fought for almost twenty years to be officially recognized as a deported resistance fighter rather than a political deportee (meaning that she was deported simply on grounds of her “race”).

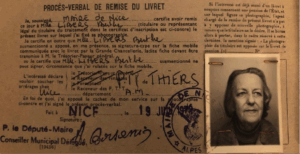

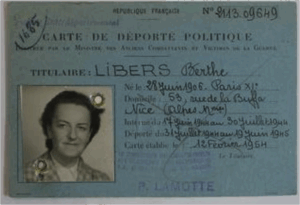

The first letter we have dates from 1946, in which Berthe stated that she was requesting the status of “deported resistance fighter”. In 1954, however, she received a “political deportee” card instead, which she clearly was not happy with.

Berthe’s political deportee card – French Defense Historical Service Archives

Berthe’s political deportee card – French Defense Historical Service Archives

We have a letter from 1965 in which she thanks the staff for having dealt with her request: “I would like to thank all the board members, and you personally, for having read and examined my request, the sole purpose of which was to claim what was rightly due to me”.

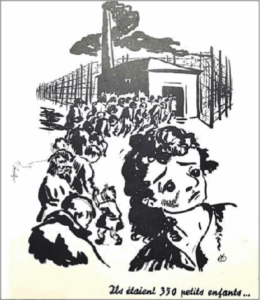

To bear witness to what she had experienced, Berthe published a short book entitled “Ils étaient 350 petits enfants” (“[Once upon a time], there were 350 little children”), illustrated by Charles Swiny and published by the Union nationale des associations de déportés, internés et familles de disparus (National union of associations of deportees, internees and families of the dead)

It tells the story of how, on July 31, 1944, 350 orphaned children were deported in a cattle car, together with their grandmothers and grandfathers, to a killing center.

Berthe told this story in the form of a fairy tale for children, simplifying the facts. For example, she refers to Hitler as “the ogre Hitler” (P.1 L.3).

The moral of the story, at the end, is “The 350 little children and the others all went up the chimney and are now in the sky; they will never again put their slippers by the fire in their homes… Thank Santa Claus, even if he never gave you anything, because it was the ogre who laid you to rest in your little white bed, and pray in your innocence that never again will the smoke of little children rise from big chimneys”

Children find this easy to understand and it is a means of condemning the atrocity suffered by the 324 children who were deported on Convoy 77. Only a handful of them, including the Urbejtel brothers, survived.

A note at the end of the book reads “A story experienced and told by Berthe Libers, Auschwitz survivor, serial number A 16760”.

The cover of the story “[Once upon a time], there were 350 little children”

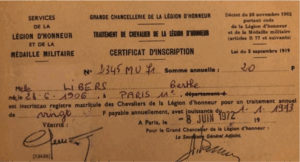

Berthe was also awarded the French Legion of Honor, as confirmed by the following documents provided by her niece, Sophie.

Records relating to Berthe being awarded the French Legion of Honor – cuttings dating from January 1, 1973 to January 1, 1978 (Family archives)

Berthe died in Nice on December 28, 1978. She donated her body to science and left her assets to various non-profit organizations and to her sister Fanny.

References to records used to compile Berthe Libers’ biography

- Leib and Esther’s marriage certificate – Paris archives – 11M 463

- Leib Libers naturalization application – French National archives 11664 X 25

- Esther Fetz’s naturalization certificate – French National archives BB/34/457

- Berthe’s birth certificate – Paris archives – 11N 329

- Paris census records – 1926 : D2M8 254 – 1931 : D2M8 397 – 1936 : D2M8 589

- Newspaper cuttings: https://www.retronews.fr

- Berthe’s account of her deportation – AN F9 5586

- Libers Berthe © French National archives in Pierrefitte : F/9/5712

- Libers Berthe © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21 P 564 386

- Arolsen Archives 3.3.2 TD File_Bad_Arolsen_103680655_0_1 et 0_2

- Philippe Barbeau and Annette Krajcer Le dernier été des enfants à l’étoile (“The last summer of the children with the stars”) – Oskar Editions (2010)

- Libers Berthe © Shoah Memorial, Paris, refs: LXXIV-11 – CDXXIV-7 – CDXXIV-7 – CDXXVI- 3 – CDXXIX-1

We would like to express our warmest thanks to Sophie de Juvigny, who kindly shared some invaluable information about her family, and to the Convoy 77 non-profit association team, who helped us with our research.

Français

Français Polski

Polski