Beya (known as Fortunée) ACHOUR, née NABETS (1886 in Constantine – 1944 at Auschwitz)

This biography was produced by students from two different classes, one in France and the other in Germany, who based their work on records held by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service and others from the French National Archives, which relate to the “Aryanization” of the Achours’ business. This comprehensive, singular file enabled the students to better understand the spoliation process, to which many Jews in France fell victim. It also tells the story of the extraordinary struggle of a woman who refused to allow herself to be crushed by the Nazi machine, and tried from every possible angle to safeguard her assets.

This biography is the culmination of research undertaken by Sara, Yasmin, Mia, Anisa and Alina from the Goethe Gymnasium in Germersheim, Germany, led by Philipp Steul and the 9th grade students from the Saint Louis middle school and Blanche de Castille high school, which belong to the Servites de Marie school group in Villemonble, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department of France, led by Tiffany Lobjoi.

BAYA ACHOUR: FROM CONSTANTINE TO PARIS

Growing up in Algeria

Beya Nabets was born on February 20, 1886 in Constantine, in Algeria.

Her parents were Bourak Nabets, a tailor born in Constantine on January 12, 1859, and Louna Ziza, born on May 11, 1861. They were married in Algiers in 1884. Her paternal grandfather was Messaoud Nabets, a jeweler, and her paternal grandmother was Messouka Itta. Her maternal grandparents were Sadia Ziza, a tailor, and Hanna Sadoum.

She appears to have been raised as an only child, as her younger brother, born soon after her, died before he turned one.

Beya was a French citizen from birth. Under the terms the Crémieux Decree, introduced on October 24, 1870, the “indigenous Israelites [Jews] of Algeria” were declared “French citizens.”

At some point, although we do not know when, Beya decided to adopt the name Fortunée. She must have felt it was nicer than Beya, which probably sounded too “oriental” in Paris.

Marriage in Paris

We do not know when exactly Beya arrived in mainland France, nor where she met her future husband, Simon Achour, who was born on May 14, 1878, in Saint Eugène, in the Algiers department of Algeria. He had been living in Paris since 1892, was studying pharmacy and went on to work as a dispensing chemist. Might it have been an arranged marriage?

Beya and Simon were married on April 7, 1908, in the town hall of the 17th district of Paris. Beya’s father was listed as “missing” and divorced from his wife, who attended the wedding in Paris and gave her consent. Simon, who was born in 1878 and was studying to be a pharmacist, lived at 156 Rue de Courcelles, the same address at which Beya and her mother lived. Beya was working as a seamstress at the time.

Simon had two brothers, Jacques, born two years after him, who was also a pharmacist in Paris[1], but was not a witness at their wedding and Léon, who was two years older than Simon.

Two daughters

The couple set up home at 26 Rue Lafontaine, in the fashionable 16th district of Paris. It was there that their two daughters were born. The first, Simone-Julie, was born not long after they were married on March 12, 1909[2]. The second, Marcelle Léonie was born much later, on November 9, 1923, also in the 16th district.

We know very little about Baya’s life prior to the German occupation, except that she had to raise her two children alone during the First World War as Simon was away fighting with the 143rd Infantry Regiment. He was invalided out of the army with a 70% disability pension and awarded the Croix des Réformés (Disabled Veterans’ Cross).

The Achour Herbalist store

A thriving business

As far as work was concerned, Baya did not pursue her career in sewing. Together with her husband, she opened a herbal medicine and perfume store. Simon, according to glowing accounts of his work, nevertheless had to continue to work as a dispensing pharmacist in other drugstores.

In September 1924, the couple sold the herbalist and perfumery business they ran at 47 Rue de la Convention in Paris’s 15th district to a couple by the name of Christen.

In March 1929, they opened “L’Herboristerie Achour” at 1 Rue Pétion, very close to the 11th district town hall on Place Voltaire. The neighborhood, not far from the Bastille and near the Père-Lachaise cemetery, was mainly a working class area, and Jewish families from Turkey were beginning to settle there.

“Beya, known as Fortunée,” owned the herbalist business, which she purchased in her sole name for “125,000 francs, stock not included”[3]. At the time of purchase in 1929, when, according to Beya Achour, “businesses had a high value,” they “paid little, and bought it outright.”.

Simon Achour managed the commercial side of the business, while his wife took care of retail sales. They employed no staff, but did use an accountant to keep the books. They were very conscientious, and their annual profits, while relatively low, increased steadily over time.

The term “herbalist” refers to the art and science of harvesting, preparing, and using medicinal plants for therapeutic purposes. It is somewhat like a drugstore, but one that only sells herbal remedies. The Achour couple also sold perfume and accessories.

Beya/Fortunée and Simon lived and worked at the same address.

According to the description of the premises by one of the administrators appointed to “Aryanize” the “Herboristerie Achour”, it comprised a ground floor with the store, a back room, a kitchen, and a basement. On the upper floor was an apartment with two rooms and a separate kitchen. The apartment has its own entrance beside that of the store. It had been rented since 1936. However, the census records for that year reveal that only the parents were living on Rue Pétion, with Baya listed as Fortunée. We know that their daughter Simone had been married since 1932: might she have taken in her younger sister when she herself became a mother?

THE “HERBORISTERIE ACHOUR” THREATENED WITH “ARYANIZATION”: A VERY COMPLICATED CASE

State-sponsored anti-Semitism

Prior to the Second World War, anyone wishing to practice herbal medicine was required to have formal training. However, in 1941, the Vichy government scrapped the qualification. The authorities began targeting the herbal medicine sector.

This crackdown on the herbalists was yet another blow to Beya/Fortunée and her husband, who, as Jews, were already under threat from a series of anti-Semitic laws that the Nazi occupiers and the collaborationist Vichy government, led by Marshal Pétain, had begun passing in 1940.

They had already registered themselves as “Jews” at their local police station (in la Roquette) as required by an order dated September 27, 1940[4], and the first decree on the “status of the Jews”, enacted by the French government on October 3,1940.

Then, in 1941, another decree was passed, this time forbidding Jews from working in various professions including pharmacy, medicine and law. Lastly, a decree dated July 22, 1941, authorized the confiscation of Jewish-owned assets.

The Achours were thus threatened on three fronts: as Jews, as business owners, and because they worked in a profession from which they were now banned. In addition, the Crémieux Decree was repealed on October 7, 1940, which meant that Jews from Algeria were stripped of their French nationality. It appears that the Achours were not aware of this, but they were now classified as “natives of the departments of Algeria.”

The CGQJ (Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, or General Commission for Jewish Affairs) soon took an interest in the Achours’ business, with a view to “Aryanizing” it. This effect of this was that Jews were stripped not only of their businesses but also of the tools of their trade and, to make matters worse, many of them were no longer allowed to work in their chosen professions. Their businesses were valued and sold off cheaply to buyers who had to prove that they were not Jewish and had no connection to the person whose property was being plundered. The proceeds went to the CGQJ.

However, the French collaborationist authorities had their work cut out for them when they tried to seize the Achours’ assets. Baya/Fortunée Achour steadfastly refused to give in, and did everything in her power to prevent her business from being Aryanized.

What happened to the Achours?

In line with the regulations on the Aryanization of Jewish-owned businesses, a provisional administrator was appointed to manage the Achours’ herbalist store. In the end, several successive administrators were involved in deciding its fate, the aim being to sell it to the highest bidder and transfer the proceeds to the CGQJ.

On May 21, 1941, the German authorities ordered “the closure of Jewish businesses if they have not yet been assigned a manager-administrator,” as reported shortly thereafter by A. Barthélémy, who was in charge of the legal liquidation process. He therefore requested that someone be appointed to this position “as a matter of urgency.”

A record issued by the General Commission for Jewish Affairs, and more specifically their Provisional Administrators Control department, reveals that the Paris Police Headquarters had appointed a Mr Houdier as provisional administrator on June 28, 1941. However, he declared himself “incompetent” and resigned from the position soon afterwards. As a result, on August 26, 1941, another administrator was appointed, this time a Mr. Gillot. His job was to keep the herbalist’s store open and look for potential buyers.

The company accounts for the years 1938–1939, 1940, and 1941 were audited to assess how much it could be sold for. The business was doing well, the accounts were well-kept and up to date. The Herboristerie Achour had no debts and generated a profit of almost 20,000 francs in 1940.

According to Mr. Gillot, the business was “small but healthy”. Purchased for 125,000 francs in 1929, its value had risen to around three times that amount by1939[5], but nevertheless, the CGQJ representative complained that the offers made for it were too low.

Beya/Fortunée insisted that she was Arabic or Kabyle

Beya/Fortunée, however, objected to this forced sale. She tried repeatedly to prove that she was not a Jew, and submitted various documents to attest to her Arab roots.

She began by declaring that she and her husband were not of the “Jewish race” but “Arab,” and that they were only Jewish by religion[6]. She stated that the surname “Achour” meant “tithe or tax” in Arabic. She then referred to her long family line of Muslim Algerian Kabyle people that dated back to the conquest of Algeria. She went on to explain that her granddaughter had been baptized Catholic in 1937 and that her daughter, Marcelle, who was still a minor, was soon to be baptized Catholic as well.

According to a letter referred to in an unsigned memo dated April 9, 1942, Mr. Gillot believed that Baya Achour was not a Jew, but belonged to the “Kabyle race.” She was, he wrote, “a descendant of Habid Achour, born around 1835, a Muslim who converted to Judaism, but whose Jewish religion was not passed down to his children,” all four of whom married Catholic women. He went on to say (incorrectly) that “Simon is Mrs. Achour’s father. I do not know if her mother was Aryan”[7]. In fact, Simon was her husband: she was born Beya Nabets. Habib Achour was Simon father, not Beya’s.

Beya Achour’s objections were a problem for the temporary administrator: although he had a number of potential buyers, some of them backed out, while others wanted to know whether or not “the company should be considered Jewish.”

By that time, however, Mr. Gillot was no longer in charge of the Achours’ business. On November 22, 1941, a Mr. Mathivat had been appointed temporary administrator, but he too had promptly recused himself. Then, on January 5, 1942, a Paris pharmacist named Raoul Bonnay was given the task, and he took over the store in February. In March, he submitted a report on the Herboristerie Achour, in which his explanation to the supervisory authorities tended to support Beya/Fortunée’s assertions about her Arab ancestry, on the basis that she had submitted supporting documents confirming that her father was an “Arab.”

It was then decided that the business was to be sold on unless Mrs. Achour could prove that she was “Aryan”. A potential buyer was found, but he only offered 40,000 francs, which was well below the true value of the business. On March 31, another prospective buyer emerged, this one a fellow herbalist based in the 19th district. He provided the necessary documents to prove his “Aryan” status and the provenance of his funds, and bid 60,000 francs, citing the low profits and the cost of registering the business in his name. In common with two other potential buyers who had pulled out because they felt the equipment was obsolete and the cost of modernization would be too high, he also emphasized the dilapidated state of the premises.

The CGQJ responded on April 9, 1942, stating clearly that it was vital to determine whether Mrs. Achour was Jewish or not before the transaction could proceed: “She must prove that she is Aryan or confess outright that she is Jewish,” and “if she is an Israelite, the offer that you sent us will be accepted in the absence of any competition.” Nevertheless, the person who wrote the letter did note that the business was worth much more than the offer.

On April 3, 1942, however, in his second report to the CGQJ, Mr. Bonnay stated that “Ms. Achour is now much more reticent about her claims”.

Baya Achour explained why she registered herself as a Jew in 1940

Beya/Fortunée’s letter dated May 2, 1942, however, reveals that she refused to give in, and continued to insist that she was an Arab. She disputed the sale, and maintained that she was not Jewish. In fact, in this letter, which is also in the Aryanization file, she explained the reasons why: “I declared myself to be Jewish even though I am Arab.” She said that she had complied with the first decree dated May 27, 1940, which referred only to being of “Jewish religion”[8]. She wrote “That applied to me, so I made the required declaration” and added “It was only later that the question of Jewishness became a matter of race.” She then cited the decree of “March 24, 1942, paragraph 1”[9] and insisted “I am of Arab race, despite being Jewish by religion.” Beya/Fortunée then requested that the CGQJ in Algeria carry out an investigation to prove that both her parents were Arabs. The letter was typed, but after that, she added by hand “as were my grandparents.”

On May 4, she sent in her parents’ birth certificates: “It is impossible to provide more details, as Constantine was not under French rule at that time”[10]. She explained that she had registered herself as “being of the Jewish religion” and, as her name began with the letter “A,” she had to do so “first thing in the morning”. Somewhat concerned about the possible implications of this, she noted that she had “asked for advice” from the “police commissioner in my neighborhood” who “told me that it would not be a problem and that it was better to comply with the rules.” “As regards race”, she continued “I am certain. I am Arab.”

On May 9, 1942, Raoul Bonnay’s “Report 3” was rather terse. He referred to the documents Mrs. Achour had submitted “to prove that she is not Jewish.” Without taking sides, he noted that her parents’ names “are typically Arabic.” Regarding the “potential sale”, he noted that the buyer had made a new, lower offer (48,000 francs). He also noted that he agreed to the rental price of the apartment, which had been set at 4,200 francs, but that Mrs. Achour could continue to live there since he had “another source of income” besides the business.

The case dragged on

Discussions between Raoul Bonnay and Vichy representatives continued until July 27, 1942, vacillating between selling the business or returning it to Beya/Fortunée if she were found to be non-Jewish.

In his fourth report, Mr. Bonnay expressed his wish to settle the matter once and for all. He said they should either deem Mrs. Achour to be “non-Jewish” and “give her house back”, or deem she was Jewish, in which case “the sale should be completed as soon as possible.” He said his six-month mandate was due to expire in a month’s time and it was “therefore urgent to find a solution a soon as possible.” He added that stock was running low but as an administrator, he was not allowed to buy anything.

On July 30, 1942, an inventory of the stock was made: as of June 30, 1942, the business had made a gross profit of 18,018.85 francs. After salaries, rent, gas and electricity, taxes, etc., were deducted, the net profit was 1,261.85 francs.

On October 12, 1942, Mr. Bonnay decided that the evidence provided by Ms. Achour was not conclusive. He had an offer of 63,000 francs, including stock. He insisted to his supervisor that the sale had to go ahead quickly, otherwise the business would have to be “liquidated.”

Astonishingly, the case dragged on further. Beya/Fortunée had a will of iron and no doubt a very good lawyer to advise her. Nevertheless, on March 31, 1943, the axe finally fell: Mr. Bonnay was instructed to sell Mrs. Achour’s business.

On July 11, 1943, the General Directorate of Aryanization of the Economy, Section III, requested the Achours’ business accounts for the “previous three financial years”.

On December 20, 1943, the French subsidiary of Barclays Bank acknowledged receipt of a check for 750 francs from Raoul Bonnay, “which we are using on behalf of the Treuhand u.Revisionsstelle im Bereich des Militärbefehlashabers in Frankreich, Paris.” It was to cover the fees of the previous administrator, Mr. Gillot.

Then, on April 19, 1944, a Mr. Jean Thomas, from the General Directorate for Aryanization of the Economy, Section III, returned to the issue in a letter addressed to Mr. Bonnay. It said that Mrs. Achour should obtain a “certificate of non-membership of the Jewish race” from the General Commission for Jewish Affairs, failing which her business would be sold to an Aryan as soon as possible.” That same day, Jean Thomas also wrote to Beya Achour directly, suggesting that she request such a certificate.

By July 1944, however, the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs no longer seemed to be in any doubt…

ARREST AND DEPORTATION

It is unlikely that Beya/Fortunée Achour ever went to the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, which was a veritable mousetrap. Either way, two and a half months after it was suggested, the Achours fate was sealed.

On July 15, 1944, either the Gestapo or the French police (accounts differ) arrested Beya Achour and her husband Simon at their home at 1 rue Pétion in Paris.

They were accused of listening to British radio, according a file that their daughter Simone compiled after the war.

Beya and Simon were interned in Drancy camp, north of Paris, on July 17, 1944. They had 637 francs on them when they were “searched”, for which Simon was given a receipt.

Two women later testified to having witnessed the arrest on July 15: the concierge, Marie Roguet or Roguel, and Marie Malissard. When contacted, the witnesses cited “Israélites”, meaning “being Jewish” as the reason for the arrest.

On July 31, Beya, Simon and 1304 other people were deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp. The train left from Bobigny station, near Drancy camp, and after a journey of over 800 miles, Convoy 77 arrived in Auschwitz during the night of August 3-4, 1944.

Beya Achour, along with her husband, was sent to the gas chambers and murdered as soon as she arrived in Auschwitz. She was 58 years old.

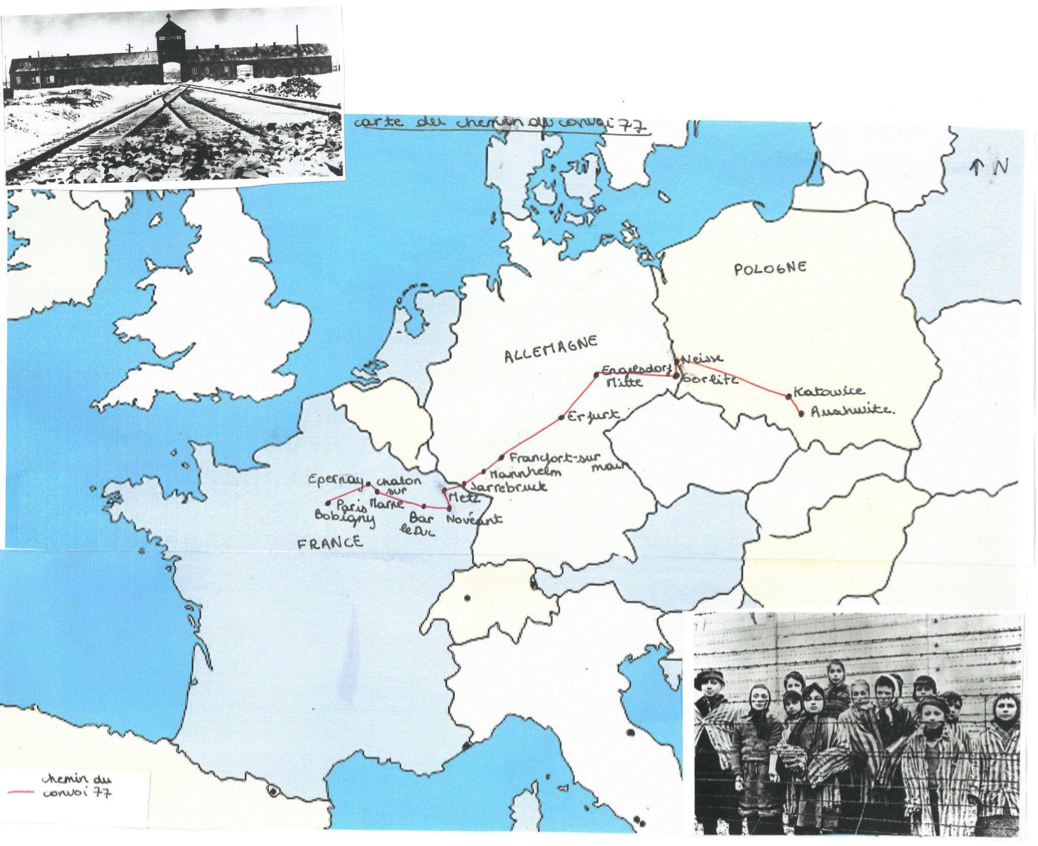

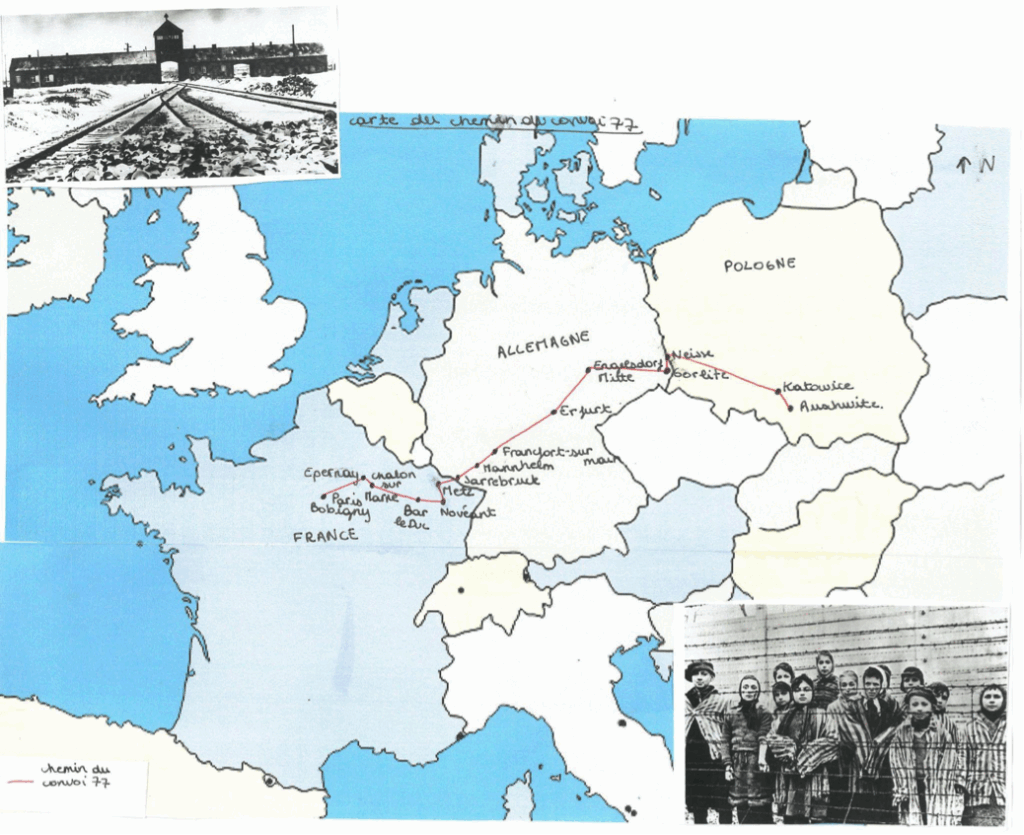

Map drawn by Alix, Julie, Bastien and Arthur

The route taken by Convoy 77: Bobigny – Noisy-le-Sec – Épernay – Châlons-sur-Marne (now Châlons-en-Champagne) -Bar-le-Duc – Noveant – Metz – Saarbrücken (now on the border between France and Germany) – Mannheim – Frankfurt -am-Main – Ronshausen Fossidorf – Engelsdorf Mette (a suburb of Leipzig) – Gorlitz (now on the border between Germany and Poland) – Neisse – Cosel – Kotowice – Auschwitz.

AFTER THE WAR

In 1946, Beya and Simon’s daughter Simone-Julie, who was then living in her parents’ old apartment at 1 Rue Pétion, began the administrative procedure to have her mother’s death officially confirmed. She gathered documentation and witness statements in order to have Beya recognized as a victim of racist persecution.

Alice Abouav, a Convoy 77 survivor who lived next door to the Achours at 3 Rue Pétion, testified in a statement dated May 28, 1946, that she saw “Mr. and Mrs. Achour being taken to the gas chambers after the Germans selected the prisoners who were unfit for work.”

An erroneous record in Beya’s file states that she and Simon passed through the Compiègne camp. The last convoy to leave Drancy on August 17, 1944, with Aloïs Brunner on board, did indeed stop to pick up some resistance fighters interned in Compiègne, but that was two weeks after the Achours were deported, and those prisoners were not taken to Auschwitz.

The French Ministry of Veterans Affairs and War Victims issued Beya’s death certificate in 1946. In 1962, her daughters Simone, who was still living at 1 rue Pétion, and Marcelle applied to have her granted “Political Deportee” status.

In 1963, as Beya’s legal heir, Simone received her Political Deportee card. In January 1965, she was awarded 120 francs in “compensation” for her loss of her mother.

Once the lengthy process of confirming that Beya and Simon had died in Auschwitz was completed, the estate was settled, and their daughters were at last able to claim their inheritance.

In the end, the “Heboristerie Achour” was never actually sold. On October 8, 1945, the head of the Restitution department at the French Ministry of Finance wrote to “Mrs. Beya Achour.” Her daughter Simone replied, in the margin of a printed questionnaire: “I have regained possession of the business, given that it was neither sold nor affected in any way.” She went on to reopen her parents’ herbalist store.

Beya/Fortunée’s extraordinary battle to safeguard her property at least served some purpose, even though, indirectly, it may well have led to her arrest.

Notes & references

[1] Jacob, known as Jacques, Achour, was deported on Convoy 67 on February 3, 1944. Cf. Shoah Memorial website

[2] In 1941, Simone was a widow with a child born in 1934, according to the Aryanization file AN AJ38 2348 14108. She remarried in 1947 and died in the 20th district of Paris in 1982. Marcelle was married in 1946 in Algiers and died in France in 1994.

[3] Aryanization file, French National archives, ref. AJ 38 2348 14108.

[4] This decree defined the criteria for belonging to the “Jewish religion” and required anyone who did to take part in a census. Jews were forbidden from leaving their area in which they lived (i.e. where they were registered), and the confiscation of Jewish businesses and shops began.

[5] Aryanization file, letter dated April 9, 1942, unsigned, loc. cit., French National archives, ref. AJ 38 2348 14108.

[6] The Nazi’s thus played with words, based on their cherished notion of the Jewish “race.” Many Jews from Muslim countries tried to take advantage of this confusing distinction, which had the added benefit of explaining why the men were circumcised, as the practice is common to both religions. The rector of the Grand Mosque in Paris testified on behalf of some Algerian and Moroccan Jews who were trying to shield themselves from arrest. The Achours were not among them.

[7] He was also a rabbi. He signed the birth certificate of his son Jacob (Jacques), Simon’s brother, in Hebrew in 1880. Achour is a surname common to both Jews and Muslims. Nabets, Nabet, and Nabeth, on the other hand, are more closely associated with Sephardic families from North Africa, particularly in the Constantine region.

[8] This refers to the one dated September 27, 1940, see above.

[9] German order of March 24, 1942, which broadened the criteria for “belonging to the Jewish race.”

[10] Beurak Naberts was born on January 12, 1859 in Constantine, Algeria. His father, Messaoud, was 40 years old at the time. Constantine was taken by the French army in 1837.

Français

Français Polski

Polski