Denise LEMEL

Editorial

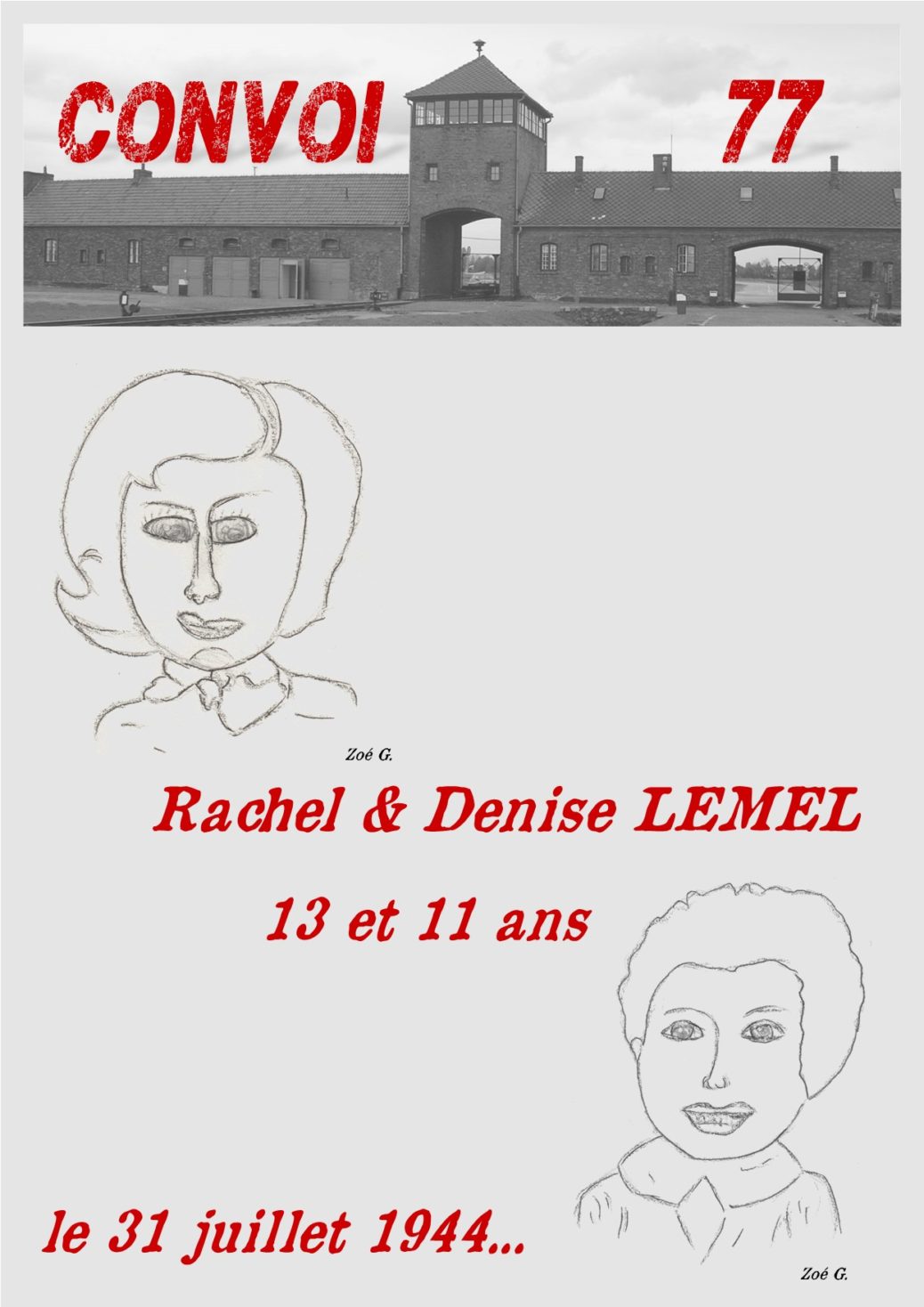

Rachel and Denise Lemel were 13 and 11 years old when they got off the train that had taken them from Drancy to Auschwitz. 13 and 11 years old when their lives came to an end one summer’s day in 1944. They were killed because they were born “Jews”, according to the Nazi definition, which was adopted by the French state. These two little girls, two of hundreds on that train, two of thousands in the short space of time between 1939 and 1945, have been the focus of your attention, you, a group of students hardly any older than these two girls, during your 2021-2022 school year.

Although nothing prepared you for this task, you now carry a torch in memory of these girls and have become apprentice historians, who learned rapidly.

Through your teamwork, which is summarized in this biography, you have been able to retrace the key moments surrounding the “final solution to the Jews” implemented by the Nazi regime and its collaborators. You take us on a journey through the French archives that details Rachel and Denise’s story, and at the same time uncover the history of the deportations from France (the racist laws, Drancy camp, Beaune-la-Rolande camp, the work camps and the Levitan camp, the UGIF children’s home in Saint-Mandé, etc.).

You draw the girls’ portraits and their family history, albeit incomplete, with great sensitivity. You take us back to their life in Belleville, where we can almost hear the sound of the sewing machines (and I even learned some terms related to the tailor’s trade that I didn’t know, despite my grandfather having become a tailor when he arrived in France from Poland).

Together with you, we follow the girls as they were arrested together with their mother, Gitla, and their older sister, Berthe; we discover that they were finally removed from the list of deportees, and you ask yourselves why, while pointing out, as would real historians, that we will never know the answer. We also follow them on their journey from Drancy to Beaune-la-Rolande and then back to Drancy.

We then discover that the UGIF, an organization founded by the Nazis, placed them in a home for orphaned girls or girls whose parents had disappeared or been interned. It was in Saint-Mandé. They lived there for a few months… until the round-up on July 21. The head of Drancy camp, Aloïs Brunner, did not want any of the people who lived in these children’s homes to escape deportation just as the Germans were about to be defeated and the Americans were approaching Paris. Meanwhile, Rachel and Denise’s mother, who had been detained in a labor camp in Paris, found out that her daughters were about to be deported, and she too was deported on Convoy 77. Only their older sister, who was not deported, and their younger brother, who had avoided being arrested, were left behind to remember them.

With your superb work, serious, well-documented and empathetic yet unsentimental, you, the 9th grade students from classes 3e3 and 3e6 at the de la Forêt secondary school, with the guidance of your teachers Nathalie Berna and Marie Pourriot, and the support of Mr. Wald and Ms. Dardaine, the Principal and Deputy Principal of your school, have contributed to bringing Rachel and Denise back from oblivion. And, through their tragic story, you have also understood the need to remain vigilant against anti-Semitism, racism and any kind of intolerance.

Bravo!

Laurence Klejman

Ms Klejman is the granddaughter of Golda Klejman, who was deported on Convoy 77.

What was the Holocaust?

The definition of the “Holocaust”, or “Shoah”

In France, the Holocaust, or Shoah, began in 1940 and ended in 1944. The term “Shoah” means “catastrophe” or “destruction” in Hebrew. It relates to the killing of nearly 6 million European Jews by Nazi Germany, simply because they were born Jewish.

In France, the term Shoah has been used since the release of Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 movie of the same name.

What is genocide?

Genocide is defined as the intention to completely annihilate a people and a society.

Genocide involves the use of extensive criminal measures by a state system.

Genocide is also characterized by the number of victims involved.

Nazism

Nazism began in 1933 in Germany and spread rapidly to the countries to the west. The regime of the Third Reich ended in 1945 when Nazi Germany was defeated by the Allies.

The Holocaust in Europe

The Holocaust heralded an abrupt shift in the history of the human race towards hatred of the Jews: anti-Semitism. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Nazi regime tried to remove Jews by forcing them to emigrate. About 150,000 Jews left Germany during the first five years of the regime, but after the annexation of Austria in March 1938, 185,000 Jews were brought into the Reich. From July 6 – 15, 1938, an international conference, aimed at finding a “solution” for the mainly Jewish refugees, was held in Evian, in France.

The year 1938, a turning point in Germany

The year 1938 was dominated by the Nazi regime’s anti-Jewish agenda. On April 26, Jews were obliged to declare all the property they owned. This was the beginning of a process called “Aryanization”. Businesses, shops and self-employed people were forced to cease trading or were confiscated.

The Holocaust in Poland

On September 1, 1939, the German army invaded Poland.

The Red Army undermined the Polish defences by applying the secret provisions of the German-Soviet pact, signed on August 23 by Germany and the USSR, which, after four weeks of fighting, partitioned Polish territory. In total, 1,900,000 Jews were living in the two zones. The first ghettos appeared at the end of 1939 in the area annexed to the Reich, and in the spring of 1940 in the area known as the “General Government” of Poland.

Lastly, the elimination of the Jews was hidden from the population through the use of vocabulary such as “Operation Spring Wind” (a code name for a “coordinated roundup in mid-July in France, Belgium and Holland… in Paris, this gave rise to the Vel d’hiv roundup” explains the historian, L. Klejman), “the final solution to the Jewish question”, “transfer to the East”, “special treatment”, etc.

The beginnings of the Holocaust in France

As of September 1940, following the German invasion in May and Marshal Pétain’s signature of armistice in June, the Jews living in France were severely affected by the new anti-Semitic legislation. From October onwards, France began to collaborate with Germany, which was occupying the northern part of France, known as the “occupied zone”. The Commission for Jewish Affairs was founded in March 1941. The Germans required the French police to arrest Jews and Resistance fighters. As of May 29, 1942, all Jews over the age of six living in the “occupied zone” had to wear a yellow star in order to identify them on the street or, in the case of children, at school. They were forbidden from working in some occupations, such as teaching and politics, and from going to certain public places, such as parks and libraries.

On July 16 – 17, 1942, a round-up took place. It was called the “Vel d’Hiv Roundup” and it led to the arrest of around 13,152 Jewish men, women and children. In the midst of the turmoil, what happened next, and their fates, varied.

Loane and Manon, 36

The beginning of our investigation

The introduction to the project

Our teachers, Ms. Berna and Ms. Pourriot, told us about the project in October 2021.

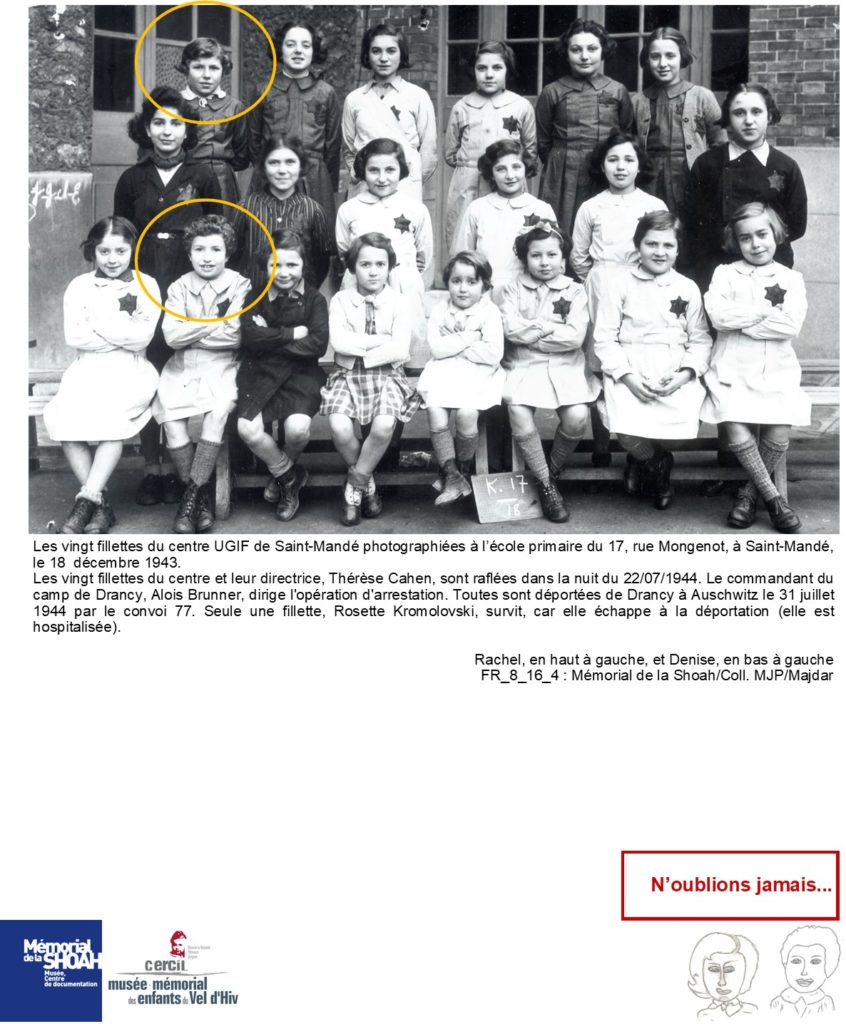

We first became acquainted with Rachel and Denise Lemel through a group phone, which we believe to be a school photo similar to those that we have taken at the start of each school year.

The first thing we noticed is that they are all girls: was it therefore a girls’ school, as was common in those days? The girls seem to be smiling.

Next, a little detail caught our eye. Almost all of them have a star sewn onto the left-hand side of their clothes.

Why were they all wearing this star?

We stepped into the lives of the Lemel family at the time this photo was taken, on December 18, 1943, in Saint Mandé. We then noticed that some of the girls are not named. Why are their identities unknown?

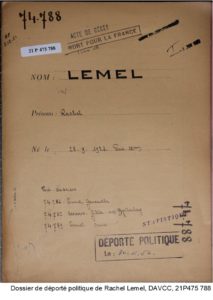

The first records found: 1956?

We then came to the first archived record available to us: Rachel Lemel’s file bearing the words “Acte de décès – Mort pour la France” (“Death certificate – Died for France”).

The file is dated 1956, twelve years after the end of the Second World War.

What had happened? Why did she have to wait eleven years, until November 30, 1956, to be acknowledged as having been a “political deportee”? And above all, why was she granted this status?

The start of the investigation

The students went through the archives meticulously, sharing their findings using a group work system. Then, step by step, they allocated the various places and contextual information that made up the family’s life story in order to write news articles.

Congratulations to the students for their perseverance and commitment to this project.

The teachers.

“Political deportee” status

The first archived records

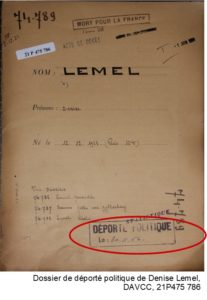

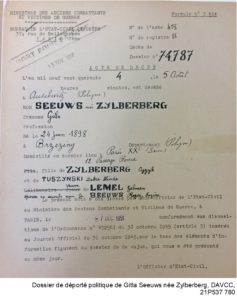

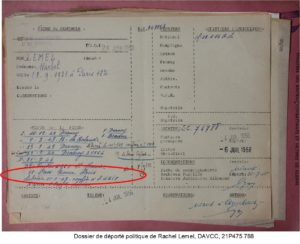

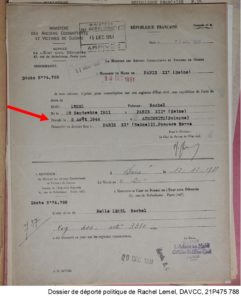

We found two administrative dossiers dating from 1956, from the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War.

The dossiers were 29 and 34 pages long, and as we read them, we entered into the lives of Rachel and Denise.

November 30, 1956. The Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War granted Rachel and Denise Lemel “political deportee” status. How come?

What does “Political deportee” mean?

Deportees were people who were arrested and deported after June 16, 1940, under the Vichy regime, when the German authorities took over in France.

Political deportees were defined as French nationals who the enemy transferred out of the country and then incarcerated or interned for any reason other than breaking the law.

The acquisition of “political deportee” status entitled the person to a “deportation grant” of 5,000 francs and to an official political deportee card, issued by the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War.

There were two different categories of deportees, the “Resistance fighters”, who were considered to be voluntary combatants, and the “political deportees”, who were defined as civilian victims arrested for any reason other than an act of Resistance. Both categories included people who were victims of racial persecution, hostages and victims of roundups, as well as all those arrested on account of their political beliefs.

The French law of September 1948

The status of political deportees and internees was established under French law no. 48-1404 on September 9, 1948. The first article of this law states “The French Republic, grateful to those who have contributed to the salvation of the country, bows down before them and their families, determines the status of political deportees and internees, and proclaims their rights and those of their beneficiaries”.

On September 9, 1948, the Deportation and Internment Medal was introduced. This medal was awarded to 76,000 people who were deported from France and/or interned in France. It should be noted, however, that while foreign nationals were able to obtain political deportee status if they had been resident in France before September 1, 1939, the distinction “Died for France” was only awarded to French citizens.

Lastly, this legislation changed the status of “racial deportee”, i.e. a person deported on grounds of race or religion, to “political deportee”.

Political internee status

A person referred to as a “political internee” was someone who was interned in France (there were several dozen such camps).

The status of political internee was granted to French citizens who, “following their arrest, for any reason other than an offence under common law, were interned by the enemy”. For foreign nationals, the law stated that “the date on which they began to reside in France must be before 1 September 1939”. They were thus entitled to political internee status.

Acquisition of political deportee status

There was a form that enabled a person who had been deported to apply for political deportee status. The form included information about the person’s civil status, arrest, internment, deportation and repatriation.

The rights of political deportees

As of 1948, “political deportees” were entitled to:

- A civilian war victim’s pension

- Compensation for loss of property

- Wear the Deportation and Internment Medal

- the support of the French National War Veterans and Victims of War Office

Margot and Ryanna, 36

Brzeziny and Rawa, early 20th century

Gitla Zylberberg was born on June 24, 1898 in Brzeziny, Poland.

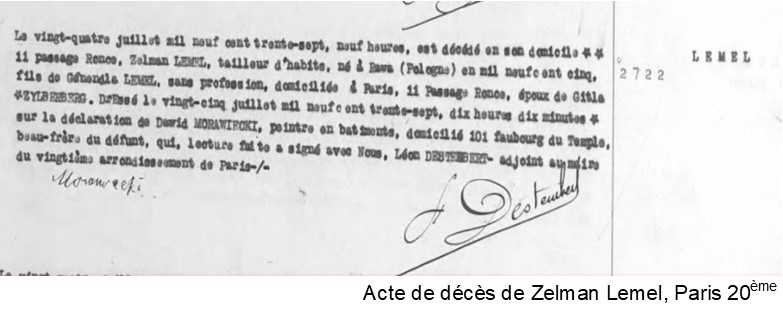

Zelman Lemel, for his part, was born in 1905 in Rawa Mazowie. The exact date on which he was born is not given on the death certificate that we found. He was the son of Genendla Lemel.

The couple got married in Brzeziny, Poland, on October 29, 1929.

They already had a little girl, Bejla or Bayla (Berthe in French), before they were married. She was born on May 25, 1929.

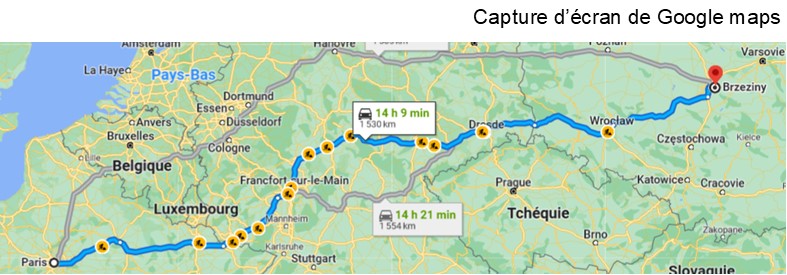

It appears that Zelman travelled the thousand miles or so from Brzeziny to Paris shortly after the wedding, as he arrived in France on November 29, 1929. The move was no doubt prompted by the rise of anti-Semitism and the proliferation of restrictive legislation in Poland.

HIs wife and daughter joined him in France on December 6, 1930.

Zelman’s mother, Genendla Lemel, and her sister (the Morawiecki family: David and Idessa, née Lemel) also moved to France).

Brzeziny

We found two towns called Brzeziny. We believe, however, that Gitla’s hometown was the one in central Poland. It was in the Lodz Voivodeship and was also the capital of the Powiat, (which means administrative area and local authority) of Brzeziny.

Brzeziny is approximately 13 miles south of Lódz, and about 60 miles southwest of Warsaw.

What was the origin of the town’s name? It is on the site of an ancient forest, a birch wood, the Polish word for which is “brzozy”.

Brzeziny during the Second World War

In May 1940, the Nazis set up a ghetto in the town. It was liquidated on May 14, 1942, at which time the survivors were moved to the ghetto in Lódz.

In May 1940, the Nazis set up a ghetto in part of the city. It was liquidated on May 14, 1942, at which time the survivors were moved to the ghetto in Lódz.

Between 1942 and 1944, 6,000 of the Jews living in Brzeziny were murdered by German forces.

Julien, 36

Rawa Mazowiecka

The town of Rawa Mazowiecka is in central Poland, in the Lódz voivodeship.

It is about 50 miles from Warsaw and under 20 miles from Brzeziny.

Malo, 36

The Lemel family left Poland for France in 1929 and 1930. As a result, they were not there to experience the German invasion. Their home towns were in fact invaded in 1939.

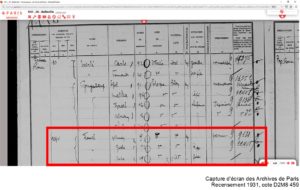

Belleville, in the 20th district of Paris, 1930

Gitla was 32 years old when she arrived in France, while Zelman as 25 and Berthe was eighteen months.

The family set up home at 12, passage Ronce, in the 20th district of Paris, in the Belleville neighborhood.

They are listed in the Paris census of 1931, living at 12, passage Ronce.

We were fortunate enough this year to have Esther Senot, who lived at 10 Passage Ronce, come to speak to us. We asked her if she knew the Lemel family, but unfortunately, she doesn’t remember them.

The 20th district of Paris in the 1930s

The Belleville neighborhood became part of Paris in 1860. The 20th district is in the east of Paris. The 20th district, which lies on the right bank of the Seine, is the last of Paris’ twenty districts.

Between 1918 and 1939, large numbers of migrants, of various nationalities, settled in the area.

They were mainly working-class people of various origins: Armenians, Greeks and Jews from Poland. They contributed enormously to the growth of the craft industry, in particular the leather industry, which was already established in Paris.

Camilia and Aubane, 33

“At the time, many Jewish immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe found their first homes in these areas of the capital, in the north, the east, and on the outskirts of the neighboring towns. […] I think that we, as Jews from Poland, were the most numerous. […] It is important to know that in the first few decades of the twentieth century, France was perceived as a promised land. Many Jews were fleeing misery and anti-Semitism, placing great hope in this country. In our family’s imagination, it was a kind of anti-Poland! The words “freedom” and “equality” inspired the dreams of a population condemned to poverty and exclusion, terrorized by pogroms or the threat of them”. (La Petite fille du Passage Ronce, (The little girl from Passage Ronce) by E. Senot, 2021, p.16)

The tailoring and pressing trade

Zelman worked as a tailor, as did many of his neighbors. From records in the file on Berthe and Henri, provided by the OSE (the Oeuvre de secours aux enfants, or Children’s Aid Society), we discovered that after a few years, he bought his own workshop.

The family continued to grow.

Rachel was born in the 12th district of Paris on September 28,1931.

Denise was born in the 12th district of Paris on December 12, 1933.

Henri was born at la Varenne, on November 17, 1936.

Sadly, Zelman died on July 24, 1937, from kidney disease and uremia.

The family then had financial problems, since Gitla was not working.

La profession

Description of the tailoring trade

A tailor is a craftsperson who cuts out and makes clothes to measure, mainly suits for men.

The tailor’s job involves cutting, sewing, making and selling clothes, and adding the finishing touches to a garment.

From the 19th century onwards, the clothing industry developed significantly. The tailoring trade was sidelined and is now part of the luxury goods sector.

Work was largely dependent on the seasons, religious holidays, cultural events and the specific needs of each client. Working hours were often irregular and dictated by weddings and religious festivals.

The tailoring trade included various different jobs. Some people cut out and prepared linings, some sewed together pants, others who made the jackets, some who made alterations and also specialist button makers.

In the inter-war period, 70% of the garment workers were Jews from Eastern Europe. In the 1840s, however, almost half of the tailors in Paris were from Germany, Hungary and Poland, although most of their workers were French. They sometimes resorted to occupations that others were reluctant to take up, such as dyeing, leatherwork and shoemaking.

“Jewish immigrants from Poland were not necessarily tailors before they came to France, and migrants tended to specialize according to their ethnic background: Italian masons first, then Spanish, then Polish Jewish tailors.” adds L. Klejman.

The Second World War had a devastating effect on the industry. Shortage of resources, economic concentration enforced by the Vichy regime, and the “Aryanization” of Jewish businesses decimated the sector. According to estimates, half of the Jewish homeworkers were deported.

Enola and Nell, 33

Zelman Lemel’s death certificate, issued in the 20th district of Paris

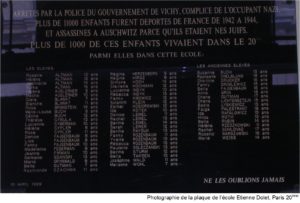

The girls’ school on rue Etienne Dolet

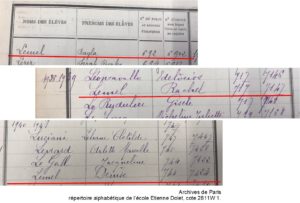

We found a record of Berthe, Rachel and Denise in the school registers, provided by the Paris Archives service.

They appear to have been in school until 1940 or 1941.

The girls’ school was in Ménilmontant, but it also took in pupils from the Belleville neighborhood.

From Esther Senot’s account, we discovered that the Belleville neighborhood was not a very wealthy area. The children spent a lot of time on the streets, which reflects a certain freedom and independence. She also explained how she remembers that “the apartments were small” and that “there were many people in the same apartment.” She adds in her book that the apartment on Passage Ronce “was very basic. In a narrow street, where no cars could go, it was in a three-story building.” (Ibid., p.16/17). The immigrant population was very prominent in the Belleville neighborhood.

Ménilmontant was a major contributor to the Paris water supply. It was there that very first telegraphs (a long-distance communication system that was fast and reliable) were received. It is located between the 19th and 20th districts of Paris.

Berthe, Rachel and Denise Lemel’s elementary school was on rue Etienne Dolet in the 20th district of Paris.

From 1933 to 1965, girls and boys studied in different buildings. The school is still open today, with teachers and 139 students split over eight grades.

During the war

The war began in 1939. The schools were evacuated out of fear that Paris would be bombed. Most of the students spent a month in the countryside, then the schools reopened at the end of 1939.

In May-June 1940, the entire school system changed as a result of the exodus. National examinations were discontinued. Children living in Paris were taken to the non-occupied zone, or to the countryside. The following year, 1941, schools reopened. The propaganda continued. Teachers had to swear loyalty to Marshal Pétain, who increased the number of school inspections. His picture was hung in every classroom.

School life was not easy. Some children suffered from under-nourishment due to lack of food in the school canteens. Since France was occupied by the Germans, it was difficult to provide enough food for the children.

As of October 3, 1940, Jews were no longer allowed to teach. They no longer had the same rights or opportunities as non-Jewish people. Jewish students were removed from the schools and were either kept hidden or were deported.

Chloé and Eline, 36

Late 1940, the census of the Jews … Summer 1942, a second marriage, perhaps for the sake of convenience

On August 18, 1942, Gitla got remarried to a Frenchman, Roger Eugène Seeuws (born on May 28, 1909 in Paris and died on August 20, 1959 in the 20th district of Paris), who worked as a roofer and plumber.

Was it a genuine love match or a marriage of convenience to allow Gitla to obtain French nationality?

We note that his name does not appear in any of the requests to have his wife’s death officially acknowledged, and that he was not involved in the process of placing young Henri in protective custody.…

The Status of the Jews

Following a German order dated September 27, 1940, Jews were obliged to take part in a census. The French Prefecture of Police circulated information about the census in the newspapers and on posters.

“Jewish nationals must therefore report to the police stations in the neighborhoods or districts in which they live, bringing with them their identity documents.”

The census took place on October 3 through 19, 1940.

Next came two laws governing the status of Jews under the Vichy regime: a decree dated October 3, 1940 and another dated June 2, 1941.

What did the decree of October 1940 cover? It excluded Jews from all civil service positions and from independent occupations and it introduced the concept of a “Jewish race”. It enabled racist, anti-Semitic policies to be put into practice.

The decree of June 1941 extended this to the whole of France, both the occupied and non-occupied zones.

It was the German order dated May 29, 1942, that made it compulsory for Jews in France to wear a yellow star. The police circulated information about this.

Naturalization is a process that enables a foreign national to obtain French nationality. It is not granted automatically. On one hand, naturalization is conditional upon several requirements, and on the other hand, an application must be made to the competent authorities.

According to the historical records relating to French nationality, a major appeal for foreign labor was made in 1919. In fact, by the end of the First World War, France had suffered a terrible human toll: one and a half million men died and more than two million people were disabled.

As a result, France needed foreign workers. This labor force came from Poland in particular. Polish Jews moved to France, thinking that they would be safe from harm in what was known as the country of human rights.

The Vichy regime, which came into being in 1940, put an end to this sense of security. The enactment of the anti-Semitic laws from September 1940 onwards meant that foreign and then also French Jews no longer felt secure.

So that foreigners could integrate more easily, a law was passed on August 10, 1927, making it easier for them to acquire French nationality. The minimum residence requirement was reduced to three years on August 10, 1927. This law also allowed children born of a French mother and a foreign father to become French citizens.

This situation was quite common. The number of naturalizations averaged 38,000 per year from 1927 to 1938. In 1938, it reached 81 000.

1940, suspension of applications for French citizenship by naturalization

The Vichy government put an end to naturalizations and criticized the 1927 law for “having made people French too easily.”

A law enacted on July 23, 1940, which was subsequently repealed in 1944, provided for a general review of all naturalizations granted since 1927.

French nationality could thus be revoked by decree. It was taken away following the decision of a special commission, which had to be composed of people and to function according to an order issued by the Minister of Justice.

500,000 cases were re-examined and French nationality was withdrawn from 15,000 people, most of whom were from Jewish backgrounds.

Under the law of July 23, 1940, numerous Resistance fighters, such as General de Gaulle, Philippe Leclerc de Hautecloque and Pierre Mendès-France, were also stripped of their French nationality.

What was it like to be Jewish in France in the 1940s?

The Vichy regime enacted a law on the “status of the Jews”. From then on, “any person born of three grandparents of the Jewish race or of two grandparents of the said race if his or her spouse is Jewish” was deemed to be a Jew. Being Jewish was therefore no longer just a matter of religion, but of “race”.

Gitla probably believed that marrying Mr. Seeuws, a non-Jewish Frenchman, would spare her and her children from being deported. “My mother remarried, I don’t know when; I think she remarried just to get French citizenship, in the hope of protecting us. I know that I saw this man again, once, when I was very young; Berthe needed to see him, I was in Paris at the time and she took me to see him; he was in hospital. […] Since then, I have never heard anything about him.” (from Vivre, aimer avec Auschwitz au cœur, 2002, p.162)

Sadly, getting married to him did not save her.

In 1945, the Vichy laws were revoked

After the Liberation, the General de Gaulle’s government re-established the republican legislation by repealing most of the Vichy laws.

On October 19, 1945, he enacted the French Nationality law.

Foreigners who had participated in the Resistance were the first people to be rewarded with French citizenship.

Elisa and Clémence, 33

Then came the arrest, at 12 Passage Ronce, in the 20th district of Paris, in December 1942

In her book La Petite fille du passage Ronce (2021), E. Senot explains that “in our little passage Ronce, 27 families were affected and 68 people were murdered.” (p.124)

The arrest, and then Drancy camp

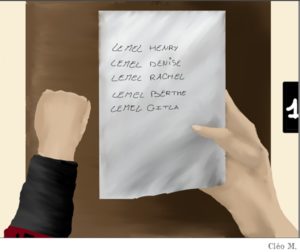

In December 1942 (on the 15th or the 16th?), the Gestapo arrested the Lemel family at their home, all except for Henri who was “at a neighbor’s house” (from Vivre, aimer avec Auschwitz au cœur, 2002, p.162) and therefore avoided the round-up. It is possible that the three daughters were not arrested at the same time as their mother because the dates on the records do not match exactly. In fact, in the French National Archives, in file number F9 5729, the date of December 16, 1942 is given for Gitla, whereas the date of December 15, 1942 is given on the Beaune camp internment records for the three girls. As for the Drancy camp internment records, the date is given as December 16, 1942.

Either way, all four of them were interned in Drancy for nearly three months.

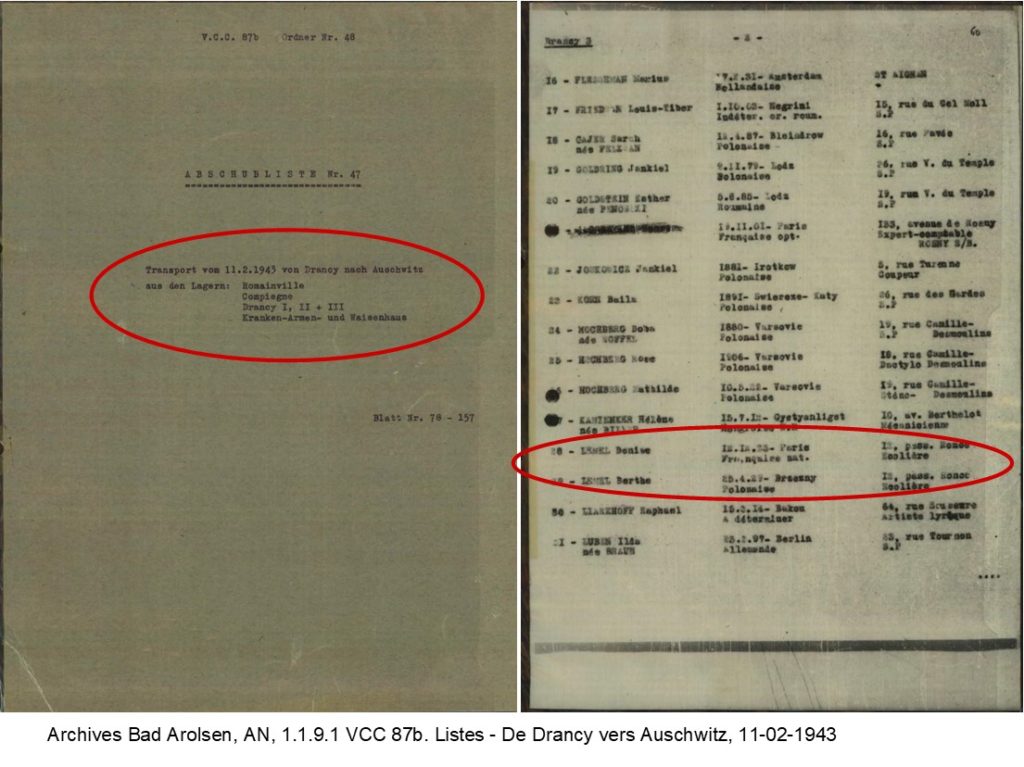

On February 11, 1943, Berthe, the eldest girl, who was then 14 years old, and her sister Denise, who was 10, were included on the list of people deported on Convoy #47 (AN_Bad Arolsen_1.1.9.1 VCC 87b. Lists – From Drancy to Auschwitz, 11-02-1943), which departed from Drancy bound for Auschwitz. We know from the archives, however, that they never actually left.…

Were Berthe and Denise not put on the convoy at the last minute because their mother was “not deportable” since she was married to a Frenchman? We don’t know.

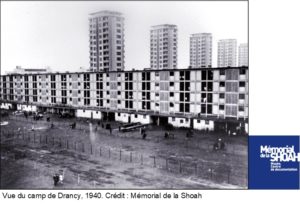

Drancy camp

Following their arrest in December 1942, Gitla, Berthe, Rachel and Denise were interned in the Drancy camp.

Drancy

Located in the north-eastern suburbs of Paris, about 3 miles from the city center, Drancy was primarily a working-class neighborhood. The site used as an internment camp during the Occupation was called the Cité de la Muette.

The origins of the camp

Drancy internment camp was the largest of the transit camps for French Jews who were deported to Nazi concentration camps or killing centers in Poland.

Initially, the camp was a group of four-story buildings forming a U-shape, with five tower blocks surrounding them. It was built in the 1930s to provide low-cost housing for local families. Construction began in 1931, continued until 1937 and was still unfinished at the start of the war.

Occupied by German troops in June 1940, the buildings were first used as an internment camp for prisoners of war and foreign civilians.

The first phase (1941-1942)

In August 1941, the Germans authorities pressurized the Police Headquarters into creating a camp intended to accommodate Jews. The camp was surrounded by a double barbed wire fence and a walkway for sentries. In addition, watchtowers were set up at all four corners of the camp. The first Jewish internees arrived on August 20, 1941. Among them were 4,230 men, including 1,500 Frenchmen.

Due to the poor sanitary conditions, 10 or so of the internees died during the first few days.

The Jewish internees slept on boards or on the floor, with neither straw mattresses nor blankets, 50 to 60 per room. Their identity papers and any money over 50 francs were confiscated from them. By way of food, they were given about half a pound of bread per day, together with three servings of watery soup with no vegetables, which they drank out of makeshift containers that they shared with others. Food parcels were not allowed. The internees did not work or do any activities other than a few camp chores. They were only allowed to leave their rooms for an hour a day, in groups, one staircase at a time.

The weaker people only went out for roll call, which took place once or twice a day. Sanitary facilities were very basic and dysentery was rife.

The 5000 prisoners who were interned in 1941-1942 had only 20 taps between them to wash themselves. Vermin flourished and the internees were eaten alive by lice and bedbugs.

The windows did not close properly and the wind blew into the rooms. In winter, the heating system was totally inadequate.

If they misbehaved in any way, the internees had their heads shaved and were sentenced to a few days in solitary confinement.

The initial, improvised approach soon gave way to the first signs of organization

The mail delivery was handled by the internees. The showers worked at last. Roll calls were made in the dormitories.

On September 20, 1941, the Red Cross was authorized to set up a permanent office in the camp and to provide supplies for the camp. At last, some straw mattresses, blankets and bunk beds arrived. Correspondence was allowed, but limited to one postcard every two weeks.

In November 1941, 750 internees were released under the supervision of a panel of doctors from the Prefecture and the German army.

In December 1941, some of the seriously sick prisoners were transferred to the Tenon hospital, and subsequently to the Rothschild hospital. However, on July 3, 1942, at 6 a.m., the French police brought all the patients back to Drancy.

Food parcels, which had been allowed since November 1, 1941, were torn open to ensure that they contained nothing suspicious. The police officers in charge of the search often took advantage of this to confiscate everything they could for their own use or to sell on the black market. Since visiting was not allowed, some families tried to catch a glimpse of a loved one from outside the camp.

On December 12, 1941, a German detachment led by Theodor Dannecker, head of the Jewish affairs department of the Gestapo in France, came to collect fifty Jews, who were then shot along with some other non-Jewish hostages. Three hundred other prisoners were transferred to Compiègne in order to fill a convoy headed for Eastern Europe. Between December 1941 and March 1942, several dozen Jews were taken from Drancy to be shot, as the Germans used the camp as a ” hostage pool “.

The beginning of the “Final Solution” in France

In spring 1942, the first few convoys set off for the killing centers in Eastern Europe.

The first convoy of deportees left Drancy camp on March 27, 1942, bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center, with 1,112 deportees on board.

The second phase (1942-1943)

This period, under the leadership of S.S. officer Heinz Röthke, was the most significant, due to the large numbers of people deported.

Over the course of twelve months, 40,000 people, mostly children, women and seniors, were deported to the various killing centers in Eastern Europe, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau. This period also included the Vel d’Hiv roundup, on July 16 and 17, 1942, when a little over 13,000 Jews were arrested by the French police. They were then crammed into the Velodrome d’Hiver, a cycle track stadium, in Paris. These 13,000 men, women and children were then interred progressively in Drancy or in the internment camps in the Loiret region, before being deported to the killing centers.

During this period, three convoys of 1,000 or so people per week were sent to their deaths. In all, 30,000 Jews were deported in three months.

The third phase (1943-1944)

In 1943, another S.S officer, Aloïs Brunner, took over as head of Drancy camp.

Despite the fact that priority was given to deportation trains, the German army encountered problems on various fronts, which slowed down the pace of deportations of Jews from France.

Life in the camp was better organized, but the Germans’ day-to-day brutality continued. There were only a few of them, so it was the prisoners themselves who were in charge of the internal organization of the camp.

In the meantime, the German authorities had replaced the French, although French police still guarded the camp.

A tragic event took place in 1944: 300 Jewish children, who were staying in children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews), were arrested and deported, including Rachel and Denise.

On July 31, 1944 (just 25 days before Paris was liberated), the final transport, Convoy 77, left Drancy with just over 1,300 deportees on board, including the 300 recently arrested children.

Summary

More than 80,000 Jews were detained in Drancy between May 1941 and August 1944.

64 transports, carrying a total of 73,853 deportees, left from Drancy.

Drancy camp is now a memorial museum, dedicated to the victims of the Shoah. It was inaugurated by the President of the Republic, François Hollande, on September 21, 2012.

Anthony, 36

Kalina and Margot, 33

* Dysentery

Severe diarrhea caused by bacterial infection, parasites or toxic substances.

Photos of Drancy camp in 1940 and 1942. Source: Shoah Memorial in Paris

Arrival at the Beaune-la-Rolande camp

For a short period of time, from March 9 to March 23, 1943, Gitla, Berthe, Rachel and Denise were transferred to the Beaune-la-Rolande camp in Loiret department of France.

We were able to find their internment records.

They were then transferred again, to Drancy, on March 23, 1943.

The Beaune-la-Rolande camp

Beaune-la-Rolande is in central France, in the Loiret department.

In 1937, there was sports field and a gymnasium in Beaune-la-Rolande.

In 1938, the sports field was taken over as a site for a large number of barrack huts (made of wood, with bunk beds lined with straw) as part of the plan to evacuate the civilian population. The barracks soon became “the camp”.

Beginning in 1940, the Germans locked up thousands of French prisoners of war there.

The German authorities expanded the camp rapidly. There were too many prisoners and some were sent to help with work on nearby farms or in the homes of local people, but mainly so that they would be fed. At first, they reported to the Kommandantur (the local representative of a German military commander) twice a week. Then they did so every morning until the day when the prisoners were no longer allowed to leave the camp. They were then transported by train and sent to the various camps in Germany, such as Dachau, Auschwitz-Birkenau, etc.

The first transport, on October 4, 1940, was the largest. In March 1941, the last remaining prisoners were evacuated to stalags (prisoner of war camps) in Germany.

The first transport, on October 4, 1940, was the largest. In March 1941, the last remaining prisoners were evacuated to stalags (prisoner of war camps) in Germany.

As of May 14, 1941, the camp took in French Jewish men who the French police had rounded up in occupied France. After the Vel d’hiv roundup, nearly 8,000 women and children were interned there, followed by some lone children whose parents had been deported.

To begin with, the Jews were occasionally allowed to go out or to have visitors. They could send and receive mail and parcels, but this was strictly monitored and censored. And then, all that came to an end.

A number of people escaped, with the help of the former deputy mayor, Henri Chevrier, and the townspeople of Beaune. However, the surveillance (carried out entirely by the French) intensified and they were then all transported by train, in atrocious conditions, from Beaune-la-Rolande railroad station to the killing centers, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek.

Internment records from the Beaune-le-Rolande camp

It was during the summer of 1942 that Jewish families, including over 3,000 people, were interned in Beaune-la-Rolande. As was the case during the Vel d’Hiv roundup (July 16/17, 1942), where Jewish families were crammed into the cycling stadium, the sanitary conditions were catastrophic.

Contagious diseases began to develop: the sick people were transferred to hospital in Red Cross ambulance cars, as were the prisoners in the Pithiviers camp, prior to being sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

Mothers were separated from their children and were deported before the children, on August 4 and 6, 1942.

“The separation of the mothers and their children was an appalling sight. Children were taken away from their parents by force,” said Annette Krajcer, who was 12 years old when she was separated from her mother. (from https://www.musee-memorial-cercil.fr/pithiviers-beaune-la-rolande/)

The children were left behind in the camp, some of them so young that they could not even pronounce their names. On August 13, 1942, the German authorities in Berlin decided to deport the children. 4,400 children were murdered on arrival in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp.

In March 1943, more than 120 Jewish internees were transferred from Drancy to Beaune-la-Rolande, including the Lemel family.

The camp was closed down on July 12, 1943 and then demolished in 1947. A vocational school was built on the site, followed by an agricultural college, which is still in operation to this day.

A memorial monument and a Wall of Names have been built in memory of the people who were interned in the Beaune-Le-Rolande camp.

Mélyne, 36

Excerpts from “Le Billet vert” (The Green Ticket), by D. Diamant, 1977

“The Beaune-la-Rolande camp was made up of twenty barrack huts, each of which could accommodate 120 to 180 people, and sometimes even 200. Some were used, entirely or partially, for camp services (shoe repairs, a hairdressing “salon”, washrooms, showers, kitchens and an infirmary, not to mention a prison hut). [This was known as “the gnouf “.] Subsequently, one hut was used as a theater and for religious services. The floors of the barracks were made of cement. Only some of them had wooden flooring. During the winter, we suffered terribly from the cold; in the summer we were overwhelmed by the heat.”

“In Beaune-la-Rolande, the internees invented an unusual means of providing themselves with footwear: they cut wooden planks out of old crates and, with whatever bits of string or strips of leather they could find, they made themselves “things” designed to protect their feet.”

The Rothschild hospital

Back in Drancy, Gitla had to undergo emergency surgery at the Rotschild Hospital in Paris on June 5, 1943, while the girls were “liberated” and taken care of by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews).

At this point, all three girls, Berthe, Rachel and Denise, were separated from their mother..

The history of the Rothschild Hospital (1852-1940)

The Rothschild Hospital was founded by James de Rothschild in 1852. He was a French banker, born into a well-known business family in Germany. His father, Mayer Amschel Rothschild (born Bauer) was born in a Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt am Main, Germany in 1744, and made his fortune in the financial sector.

Known as the “Jewish Hospital”, the Rothschild Hospital was initially intended to treat and accommodate Jewish people. It first opened on May 25, 1852.

Originally located on rue de Picpus in the 12th district of Paris, it was a hospital and hospice for elderly Jews. Then, from 1912 to 1914, at the initiative of Baron Edmond de Rothschild, the hospital was completely rebuilt on rue Santerre, so that it could accommodate more patients. By 1937, it had 340 beds. The old hospital became a retirement home. During the First World War, it was designated as an auxiliary military hospital and took in wounded soldiers and civilian casualties, irrespective of their religion. In the aftermath of the war, it reverted to its original purpose as a hospital for Jewish patients.

The Rothschild Hospital during the German occupation (1940-1944): a hospital converted into a detention center

When war was declared in September 1939, parts of the hospital were closed. During 1940, some departments were reopened, such as the maternity ward. However, it wasn’t until November that the general medical department began to take in patients again. Resistance fighters tortured by the Gestapo (the German secret political police) were treated there, but it was mainly used for sick Jews from the Drancy internment camp, before they were deported to the concentration camps, Auschwitz in particular. In December 1941, the Police Headquarters requisitioned 140 beds to care for the Jewish prisoners from Drancy. The hospital was surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by the French police. During the Nazi occupation, the Rothschild Hospital was turned into a “prison hospital”.

This hospital, mainly for Jews, kept a patient list which was an important source of information for the Nazis. It was the only one to admit Jewish women, so that they could have their babies there, and thus the children were registered at birth. From 1941 onwards, this prison hospital was the only hospital where Jewish doctors were still able to practice and thus the only place where Jews could be treated.

A resistance network was organized: doctors and nurses tried to save Jewish children by claiming that they were stillborn, for example.

At the time of the Vel’ d’hiv round-up, on July 16 and 17, 1942, the French police arrested 13,152 people, including 4,115 children. Some of them were sent to the Rothschild hospital for treatment and sometimes, if they were lucky, saved by the resistance network set up by the hospital social worker and her assistant. The doctors made out that illnesses lasted longer or invented them, kept fake death registers and helped people to escape.

A number of priests were part of the hospital’s network, such as Abbé Ménardais, who helped to save children by providing fake christening certificates. Convents or families then took in the children. Ten thousand children are said to have been saved by this network, although there are no written records to prove it.

In 1943, the SS officer Aloïs Brunner (who had been in charge of Drancy camp since June 18, 1943) turned the hospital buildings into an internment camp and organized for mothers, seniors, sick people and children to be deported directly from the hospital in order to fill the convoys to Auschwitz.

In 1944, the German authorities took over the hospital. The staff were also then treated as prisoners.

On August 18, 1944, the FFI (Forces Françaises Intérieures, or or Interior French Forces) liberated the hospital. On the same day, the Swedish consul, Raoul Nordling and the Red Cross went to Drancy camp, which the Germans had abandoned, and assured the 1467 remaining prisoners that they were safe and free.

What was the connection between the Rothschild Hospital and the Lemel sisters?

Rachel and Denise Lemel were born in the 12th district of Paris in 1931 and 1933, most likely in the Rothschild hospital. At that time, the maternity ward was not open only to Jews, but was designed to accommodate them, since it adhered to Jewish religious food and hygiene rules. Affiliated to the Rothschild Foundation, it was a non-profit institution.

Clément and Gauvain, 36

Romain and Shun, 33

The entrance to the Rothschild hospital. Source: Shoah Memorial, Studio Rolland F’AJ collection

The Levitan camp

After her stay in the Rothschild hospital, the Germans sent Gitla to one of Drancy’s three sub-camps in Paris: the Levitan camp. During her time there, she sorted belongings that had been confiscated from the Jews. She was there until July 27, 1944.

This was considered an “advantage”: life there was less harsh than in Drancy. She was granted this “privilege” because she was married to a non-Jewish Frenchman, meaning that she was the spouse of an Aryan.

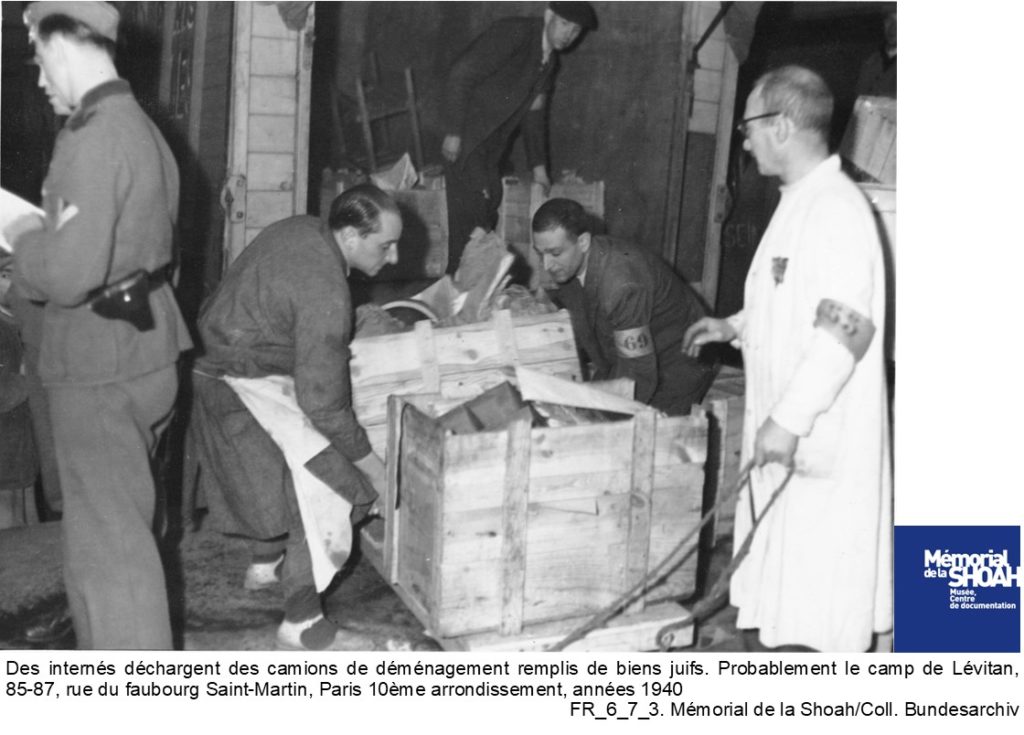

The entrance to the Lévitan furniture shop at 85/87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin in the 10th district of Paris, in 1943-1944. Source: Shoah Memorial, Bundesarchiv collection.

Background

The Levitan furniture store was founded in 1920 by Wolf Levitan, born on December 2, 1885, in Misnitz (Myszyniec), Russia.

The Levitan store was located at 85/87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin in Paris. In the summer of 1943, the Dienststelle Westen (Western division), which was in charge of looting Jewish property in Paris from 1942 to 1944, commandeered the building. This organized looting (in France, Belgium and the Netherlands) was called “Operation Furniture,” according to L. Klejman. It then became a labor camp: the Lager-Ost (East Camp). 120 internees from the Drancy camp were transferred to the Lager-Ost or Levitan camp on July 18, 1943, including Giltla Lemel.

Giltla Lemel worked in this camp. The inmates worked for the Nazis during the day and were supervised by the German forces. On the upper floors, they sorted the large number of items that arrived each day. They emptied them, cleaned their contents and methodically arranged all the loot (goods obtained by robbing someone by force, fraud or abuse of power) from the plundered Jewish possessions. In the evening, they were given a little food and slept on the top floor. From time to time they were allowed to go out onto the terrace, which was their only opportunity to get some fresh air and daylight. During their imprisonment, which had to be kept secret so as not to generate complaints, the residents of the rue du Faubourg Saint Martin were barely even aware of what was going on inside the camp because the windows were blacked out so that no one could see what was going on.

Liberation

On August 12, 1944, the Jews who had not been deported (about 740) and who were still in the Lager-Ost were transferred by bus to Drancy. Some of the prisoners, about 16 of them, escaped on the way and the others were finally liberated on August 18, 1944.

Gaëtan and Matthieu, 36

Internees unloading removal trucks loaded with Jewish belongings. Photo probably taken at the Lévitan camp at 85-87 rue faubourg Saint-Martin in the 10th district of Paris during the 1940s. Source: Shoah Memorial, Bundesarchiv collection

The three forced labor satellite camps in Paris

There were three forced labor camps in Paris that were subsidiaries of the Drancy camp. They were known as the Dienststelle Westen: the Lévitan camp (85-87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin, in the 10th district of Paris); the Austerlitz camp at 43 quai de la Gare in the 13th district of Paris, where looted Jewish property was assembled and sorted; and the camp at 2 rue de Bassano, a former mansion that belonged to a Jewish family named Cahen d’Anvers (This was where L. Klejman’s grandmother spent her final months, before she was deported. Luxury furs and high-end clothing were made there).

Rachel and Denise at the St-Mandé children’s home

Berthe, Rachel and Denise were “liberated”: they were then taken in by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews).

Presumably, the three sisters were separated at this point since Berthe was sent first to the home on rue Lamarck and then the one rue Vauquelin, while Rachel and Denise were went to the home at St Mandé-les-Tourelles.

They then became what were known as “blocked children”: they were released from the camps but were still considered prisoners.

The UGIF homes

The creation of the Saint-Mandé center

The Saint-Mandé center was inaugurated at the beginning of June 1943. It was set up on the initiative of Elie Danon, supported by the Jewish community of the 11th district of Paris. Elie Danon instigated. He worked as a “sales representative for fabrics”. He later became vice-president of the Fédération des Sociétés Juives de France (Federation of French Jewish societies). In 1940, he was a member of the Comité de coordination des œuvres de bienfaisance israélites du Grand-Paris (Coordinating Committee of Jewish Charities of Greater Paris).

On November 29, 1941, he became head of the canteen service. The center did not open immediately, but on Sundays it took in several dozen children who were later placed in UGIF* homes on rue Guy-Patin and rue Lamarck and in the Rothschild orphanage.

The Saint-Mandé children’s home : UGIF Center 64

The new UGIF center was located in a former maternity home owned by a Dr. Pitowski. It had space for about 20 beds, and was near the Bois de Vincennes, in Saint-Mandé. It was intended to accommodate young girls in poor health and opened in July 1943.

Twelve girls were transferred there on June 1. Ten days later, six more girls arrived. The first manager of the home was Sam Modjar. Clémence Mosse took over as manager during the years 1943-1944 and was then followed by Thérèse Cahen and Salomon Dubowsky. The girls in the Saint-Mandé children’s home went to the local school each morning and afternoon, where they were taught by Thérèse Cahen. When they were not at school, the girls could take part in activities such as sewing, theater and choir. They could also go for walks in Saint-Mandé, supervised by a lady who went with them. The children also went on group outings. On Sundays, Elie Danon took the children out. These outings enabled the children, who in many cases were orphans, to go out for a day to distract their thoughts. There was a family atmosphere during these outings, which the children would otherwise no longer have been able to experience. The day was spent with a host family, who they visited every week. During these outings, the girls wore uniforms or a special outfit such as pale or black smocks.

The round-up at the Saint-Mandé home

The roundup took place during the night of July 21 to July 22, 1944 in the UGIF homes in and around Paris. The roundup in Saint-Mandé began on Saturday, July 22, 1944, at UGIF center at 5 rue Grandville.

The twenty children in the house were rounded up. The girls from the Saint-Mandé home were taken to Drancy, where they stayed for a week.

The children were then deported on July 31, 1944 on Convoy No. 77, together with just over 1,300 other people. It was the last train to leave the Bobigny station for Auschwitz.

Commemoration

In April each year, the municipality of Saint-Mandé organizes a ceremony in memory of the children and the manager who were rounded up in the home and subsequently murdered in Birkenau. The names of the manager and the twenty girls from the Saint-Mandé children’s home are read out one by one. On May 30, 1948, the mayor of Saint-Mandé, Jean Bertaud, unveiled a commemorative plaque on the façade of the building in memory of the residents of the home.

Océane and Gwendoline, 36

* The UGIF

The Union Générale des Israélites de France (General Union of French Jews) was a Jewish-run organization. Its main purpose was social welfare: the UGIF paid out allowances to Jews who had no income and financed soup kitchens and hospices. All Jews living in France were obliged to join. The leaders of the institutions were the French Jewish elite.

The UGIF acted as an intermediary between the Jews and the Germany occupying forces in the northern zone and between the Jews and the Vichy government in both zones. It was set up at the behest of the Nazis, along the same lines as the Judenrats (Jewish Councils) in other occupied countries in Europe. The UGIF soon proved to be a means of facilitating the German forces’ objectives.

Amandine, 33

A page from Rachel Lemel’s political deportee dossier, from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service.

In memory of Rachel, Denise and their mother, Gitla

The twenty girls from Saint-Mandé UGIF home, photographed at their primary schoolat 17, rue Mongenot in Saint-Mandé on December 18, 1943. Rachel on top left and Denise on bottom left (circled). Source: Shoah Memorial, MJP/Majdar collection.

Rachel and Denise, heading for Birkenau on Convoy 77

Thanks to the work of Jean Laloum in, “Les maisons d’enfants de I’UGIF : le centre de Saint-Mandé” (“The children’s homes of the UGIF: the Saint-Mandé center”) on pages 58 to 109 of Le Monde Juif 1995/3 (N° 155), several pieces of information come to light.

First of all, “when the news of the UGIF children’s homes roundup reached Gitla, she asked to be transferred from the Levitan camp in Paris, where she was being held as the “spouse of an Aryan”, to the Drancy camp. It is even reported that a German soldier at the Levitan camp tried to dissuade her by trying to convince her that there was no point in doing so, but it was to no avail.” (p.102) Gitla was therefore deported, at her request, at the same time as her two daughters.

The story of Convoy 77

In late July 1944, the Allies were fast approaching Paris. In addition, an attempt on Hitler’s life had failed a week earlier.

Aloïs Brunner (1912-2001) was the commandant of the Drancy camp at the time. He personally wanted to ensure that all the children in the care of the UGIF were deported.

In response to these events, he took advantage of the confusion to send his commandos to round up all the residents of the UGIF homes around Paris. Hundreds of children and eighteen infants were sent to Drancy between the time of the Allied landings and the departure of Convoy 77.

Convoy 77 left Drancy on July 31, 1944, with 1306 men, women and children aboard. It was the last large convoy of deported Jews to leave Drancy and it was hurriedly organized. Despite the fact that the railroad workers were on strike, they did not try to stop the train from leaving, even though the Americans and the British were so close.

Convoy 77’s journey

The convoy left Drancy on July 31, 1944 from the Bobigny railroad station. Over a period of three days, it passed through several cities such as Epernay and Lérouville in France, Mannheim Erfurt and Leipzig in Germany and Liegnitz, Neiße and Kattowitz in Poland. The deportees made the whole journey in cattle cars. Yvette Levi, a Jewish deported Resistance fighter who survived, recalls: “They crammed us in about a hundred per cattle car. It was impossible for all of us to sit down: half of us sat and the other half sat on our girlfriends’ laps. We swapped over every 10 minutes or so. Da They crammed us in about a hundred per cattle car. It was impossible for all of us to sit down: half of us sat and the other half sat on our girlfriends’ laps. We swapped over every 10 minutes or so. In each car there was one bucket of drinking water and another bucket for use as a toilet. There were plenty of cans of sweetened Nestlé milk for the children, but there was no water to make their bottles. The heat was terrible, the youngsters were dying of thirst and so were we. As the journey went on, the bucket filled with excrement. As the train braked, it finally overflowed. From that moment on, we couldn’t sit down anymore, it was wet all over and oh, what a smell!”

The convoy finally arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 3, 1944. Straight away, a selection was made between those who were fit for forced labor and those who were not, including people over the age of 50, children, and anyone holding a child by the hand. It was then that Gitla, Rachel and Denise Lemel were sent to the gas chambers to die: their file states that they died on August 5, 1944.

The human toll

Of the 1306 people who were deported on Convoy 77, half of whom were French citizens, 832 were murdered on arrival at Birkenau. This corresponds to about 64% of the convoy. The other 474 deportees began forced labor. 250 of them (157 women and 93 men) survived the forced labor and the various hardships at the end of the war, in particular in May 1945. Ultimately, about a fifth of the deportees survived the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Hugo, 36

Rachel and Denise in Birkenau

Once again, thanks to the work of Jean Laloum in, “Les maisons d’enfants de I’UGIF : le centre de Saint-Mandé” (“The children’s homes of the UGIF : the Saint-Mandé center”) Le Monde Juif 1995/3 (N° 155), we learn on page 104 that “on the selection ramp at Birkenau, according to a Convoy 77 survivor, Janine Akoun, Gitla was sent to the line of women fit for work.” However, she refused to be separated from Rachel and Denise and went with them to their deaths. It is not clear precisely when they were murdered after the train arrived in the middle of the night, but the records list an officially-designated date “for convenience”: August 5, 1944.

Gitla Seeuws, married name Lemel, née Zylberberg, died on August 5, 1944 in Birkenau. She was 46 years old.

Rachel Lemel died on August 5, 1944 in Birkenau. She was 13 years old.

Denise Lemel died on August 5, 1944 in Birkenau. She was 11 years old.

Construction of Birkenau

Firstly, the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp complex was built in the south of occupied Poland, on the ruins of the former village of Brzezinka (Birkenau in German) and in the commune of Oswiecim (Auschwitz in German). Auschwitz II, also known as Birkenau, was built on the initiative of Heinrich Himmler, who was known as the Reichführer of the SS. It opened on October 8, 1941.

Birkenau included a killing center, built in late 1941, and a second concentration camp for forced labor, built in the spring of 1942.

The Birkenau killing center was equipped with five gas chambers (“red building” (KI), “white building” (KII), “KIII”, “KIV” and “KV”) and a number of crematoria, each of which could hold 2500 prisoners. There were about 300 barracks in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The first murders took place in March 1942.

The camp covered an area of around 420 acres and was surrounded by nearly 10 miles barbed wire.

The stages of the deportation process, ending in the killing center

The selection and elimination process was deliberately pre-planned and organized.

The deportees arrived in cattle cars (each of which had 1 bucket of water for about 50 people, no food and very little light). Some people were already dead by the time they arrived, from thirst, hunger or disease. “Freight cars, locked from the outside, and on the inside, mercilessly piled up like cargo, there were men, women and children, on their way to oblivion, to the depths, to the abyss. But this time, it was us who were inside”, wrote Primo Levi, a Jewish man who was deported from Italy to Auschwitz and liberated in 1945, in his account Si c’est un homme (If This is a Man).

Next, a selection process took place as soon as the train arrived. The new arrivals were ordered to form two lines: men and boys on one side, women and girls on the other. SS doctors made the selection.

Finally, the people who were deemed “useful” were forced to naked and were then shaved from head to toe to prevent lice, as well as to help erase their identity. As of spring 1942, all deportees considered “useful” were tattooed with a number on their left forearm. This tattoo was intended to replace their name. From then on, they were no more than a number. They were given one set of clothes, which they kept for the entire duration of their internment.

The gas chambers

The gas chambers could hold about 2000 people at a time.

The gas chambers in Birkenau were made up of three sections. The first section was a changing room where people who were considered “not useful” (women, children, the elderly, etc.) had to get undressed.

The second was a fake shower room, heated and with shower heads, where all the people were locked up to be murdered with Zyklon B gas.

Finally, the third section was the crematorium, where the bodies that had just been gassed were burned. The bodies were also inspected to see if they had any gold rings or teeth.

The human toll

In total, about 1.1 million people were killed in Birkenau, including 960,000 Jews, 75,000 Poles, 21,000 gypsies and 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war.

Zoé and Louison, 36

Alyxane and Marie, 33

Auschwitz

The Auschwitz camp, now referred to as Auschwitz I, was located in occupied Poland. The SS decided to set up the camp in February 1940 and it opened on May 20, 1940.

It was primarily a concentration and forced labor camp. It was located on the site of a former Polish army barracks in Oswiecim, which the Nazis had integrated into the Third Reich.

The people deported to this camp were political opponents, Jews, Gypsies, politically motivated priests and clergy, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals and “anti-social individuals” such as criminals, vagrants, etc.

March 1, 1941: The Reichführer S.S. and head of the German police, Heinrich Himmler, was worried about the capacity of the camp, since the neighbouring factories used prisoners as forced labourers. During his visit, he ordered both the enlargement of the Auschwitz camp so that it could hold 30,000 prisoners and the construction of an adjacent camp: Birkenau.

September 3, 1941: the first mass gassing of prisoners took place at Auschwitz. Tests were carried out in an improvised gas chamber in the basement of block n°11.

Emma and Lou-Anne, 33

Berthe and Henri, who stayed in France

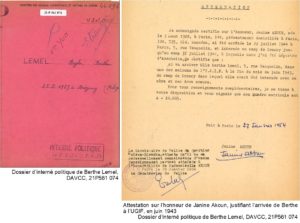

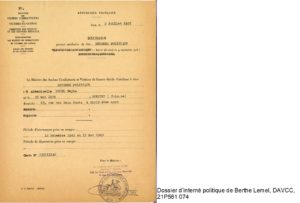

Unlike her mother and two younger sisters, Berthe avoided being deported.

In fact, in a file kept in the archives of the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen (file number 21 P 561 074), in her 1953 application for the status of political internee, she recounted her story:

“Arrested on December 16, 1942, I stayed in Drancy until June 1943, when my mother was admitted to the Rothschild Hospital. My two sisters and I were placed with the UGIF, at 2 rue Lamarck in the 18th district of Paris, and then again with the UGIF at 5 or 7 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district. During an outing, I managed to escape and went to the home of a friend of my mother, Mrs. Ziegler, at 70 Boulevard Davout, where I stayed until the Liberation. My two sisters were transferred back to Drancy from where they were deported to Auschwitz together with all my UGIF friends, in particular Evelyne Khan and Jeanine Akoun, who later came back from Auschwitz.”

(Paris, December 29, 1953)

Pages from Berthe Lamel’s application for the status of political internee. Source: DAVCC

In 1957, Berthe was granted the status of political internee

According to her written account, which is kept in a file in Caen (21P561 074), Berthe hid at the home of Mrs. Ziegler, a friend of her mother, until the Liberation.

The documentation provided by the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, or Childrens’ Aid society), states that she was taken care of by the OSE from 1944 to 1948 and that she was “a ward of the Nation until she came of age.”

When the war ended, Berthe was 16 years old. In January 1946, we know that she was placed with a certain Mr. Reiter, in Lyon, and that she had had no news of her little brother Henri, since July 1945. She did not know whether he was alive, sick or dead.

We also know that a number of letters were sent in order to put Berthe back in touch with her little brother. At the time, she was working for a furrier in Passage Coste, where she earned 2400 francs a month, 1000 of which she paid to Mr. Reiter. He was later transferred to Paris and Berthe went with him.

She undertook numerous official formalities in order to have her legal rights recognized.

As of November 1947, Berthe was too old to continue to receive support from the OSE, but she was not well enough to live on her own. On November 29, 1950, the OSE applied on her behalf French citizenship.

In 1951, Berthe got engaged to Mr. Pierre Yun, a Chinese man born in Paris in 1932, who was unemployed at the time.

On September 10, 1952, Jean-Patrick Yun was born.

In the early 1950s, Berthe began a series of administrative procedures: she applied to have her mother and her two sisters recognized as political deportees and for herself to be recognized as a political internee. This was granted and she then filed for “claims against Germany”.

She also wanted to open a hosiery workshop. They were living in poverty (with no heating, furniture on loan from the OSE and clothes donated by the OSE for their son). Subsequently, Berthe ran the Finette company (which made knitwear and sweaters) at 40 rue Bréguet, in the 11th district of Paris.

We sent a letter to Berthe Lemel’s son and grandson to share our work, but unfortunately, we did not receive a reply.

Henri, a hidden child

During the war, after his mother, Gitla, was arrested, the Entraide Temporaire (Temporary Assistance) organization took care of Henri. In his account in Vivre, aimer avec Auschwitz au cœur (Living and Loving with Auschwitz in mind), published in 2002, he says that he was first “placed with Mme Rivière, in Jouy, who entertained Germans in her home (p.163). He was then taken away from her and sent to Sours.

In May 1947, a Family Council meeting was held to discuss the Lemel children. It took place at the Clerk’s Office of the Justice of the Peace in the 20th district of Paris. It was proposed that a cousin of the family, Ms. Braun, née Butler, take care of the two children, but this did not happen.

We know that in April 1949, Henri was entrusted to “Mrs. Roger, in Moulin Neuf, in the municipality of St Priest, Jouy.” (Ibid., p.163) This woman was a war widow with a young daughter. Henri stayed there until he was 15 years old. He was enrolled at the local school in Jouy “until he passed his school certificate.” (p.164).

After that, he went to the junior high school in Chartres for a few months, and then was taken from the Roger family.

Still in the care of the Temporary Assistance organization and the Ministry of Veterans Affairs, he ended up in a children’s home in the Château de Laversines, near Creil, which had been donated by the Rothschilds. He left there with no qualifications, no trade and no vocational training certificate.

Henri and Berthe rarely saw each other, as the distance between them made it difficult.

In 1953 or 1954, he went to stay in a kibbutz in Israel. He liked it there, but because he spoke French, they wanted him to move to a different kibbutz. He and his three friends refused to go, and therefore returned to France.

He did various low-paid jobs and then found work in a garage. We discovered from the file provided by the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, or Children’s Aid Society) that as of January 1957, he went to live with his sister, Berthe.

Around this time, Henri met his future wife, Marie-Rose, and they got married in March 1957. The couple had one son, Philippe, who was born in June 1957. Henri then got a job in a small metallurgy company, where he worked until 1958. Finally, he went to work for Renault, where he remained until 1993.

Henri died in 2012.

Sources:

1. Source : DAVCC, 21P 475 788

2. Source : DAVCC, 21P 475 786

3. Source : DAVCC, 21P 537 780

4. Source : DAVCC, 21P 561 074

5. Archives de Paris, D2M8 459

6. Mairie de Paris, 20ème

7. Archives de Paris, 2811W1

8. Archives Bad Aroslen, 1.1.9.1 VCC 87b listes

9. AN, F9 5745

10. AN, F9-5770-30853 L

11. AN, F9-5763-296485 L

12. Memorial de la Shoah

13. Yad Vashem

Français

Français Polski

Polski