Eliezer ZLASKINE (1889-1944), from Jaffa to Paris

This biography was researched and written by two classes of 12th grade students from the Victor Louis high school in Talence, in the Gironde department of France.

It was undertaken as part of a year-long Civics and Ethics project, under the guidance of Ms. Tanty and Ms. Boutet during the 2022-2023 school year

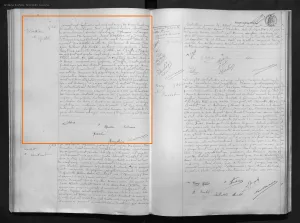

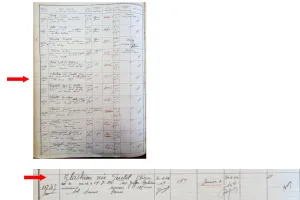

We had very few records available to help us piece together Eliezer Zlaskine’s life story. The Convoy 77 non-profit organization team sent us copies of the Drancy camp records and the general register from the Paris City Hall. Our research uncovered her marriage certificate in the Paris departmental archives. It was this that provided us with the most information but also raised a number of questions. Based on this small amount of information, we have sketched a portrait of this woman and her extraordinary journey: she was born in Palestine at the time when it was occupied by the Ottoman Empire, most probably into a very humble family. She later moved to Paris, where she got married but had no children. She continued to live in Paris until she was interned in Drancy and then deported.

At the end of the 19th century, almost 60% of the world’s Jewish population lived in the Russian Empire. There was, nevertheless, a great deal of anti-Semitism there, which led to pogroms as early as the 1830s. In 1881, almost 200 Jewish towns and villages in Eastern Europe were attacked. Jews were beaten and killed, their stores looted and their houses burned down. This was what prompted many Ashkenazi Jews to emigrate, mainly to Western Europe and the United States. Meanwhile, in his 1882 pamphlet entitled “Self-Emancipation”, Leon Pinsker advocated the founding of a Jewish state. This marked the beginning of the First Aliyah (the term used to describe migration to the Land of Israel): Jews from Yemen, Russia and Romania moved to Palestine, where a small community of around 20,000 people (mainly from the Russian Empire) swelled the ranks of the 25,000 strong Jewish community that had already been there for several generations. The newcomers lived mainly in Jerusalem, Hebron and Jaffa. These immigrants lived in extreme poverty, struggling with the very different climate and landscape. It was probably against this backdrop of recent Russian emigration to Palestine that the Zlaskine couple was born, at a time when the very first Zionist ideas were developing.

Palestine had been a province of the Ottoman Empire since the 16th century. The Ottoman Empire was home to just 3% of the Jewish population, and Jews lived in harmony with the Muslim population, as did people of other religions. Although they paid the “jizya” (a tax levied on non-Muslims throughout the Ottoman Empire, intended to protect them), they still had a certain extent of religious, cultural, linguistic and administrative autonomy.

By the mid-1880s, the three Palestinian provinces were home to between 400,000 and 460,000 people, including 40,000 Christians, mainly in Nazareth and Bethlehem, 40,000 Bedouins, who were scattered across the Negev and Transjordan, and 45,000 Jews, who were mainly concentrated in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, Tiberias and Jaffa. Jaffa, a port city with a population of around 10,000 (compared with 22,000 in Jerusalem, for example), was mainly run by European merchants.

Palestine, as one of the oldest provinces (from 1517) in the Ottoman Empire, and the richest of them after Lebanon, benefited not only from the cultivation of the coastal plains, but also from the beginnings of integration into the international market. The main products were olives and Jaffa oranges, which appeared on European tables as early as the 1870s, and cotton, which was introduced in 1860. Food factories were built to process the agricultural produce, making olive oil, soap and Nablus cotton fabrics in particular. France played a major role in the Palestinian economy as merchants opened businesses there and sold both French products in Palestine and local goods to Europe.

At the same time, the European powers, seeking to extend their spheres of influence, competed with one another to build schools, hospitals and cultural centers, and to increase consular work. Regular shipping lines linked the Levant to Europe, while the telegraph was introduced in Palestine in 1864. Tourism began to develop, first for religious visitors, then for general tourists. The Cook travel agency set up in Palestine in the late 1860s, and Jaffa became the main arrival and departure point for pilgrims and travelers to Jerusalem. Lastly, starting in the early 1880s, Baron Edmond de Rothschild encouraged the foundation of Jewish settlements in Palestine.

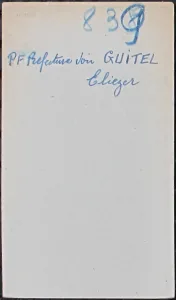

Presumably, Eliezer’s family were among the migrants who fled the pogroms in their homeland in Eastern Europe. In fact, Eliezer’s maiden name was Guitel, a family name derived from “guite”, a Germanic name which comes from “wid” meaning wood or forest. (source: www.filae.com/nom-de-famille/GUITEL.html).

For the Jewish immigrants, Palestine was a land of their dreams, safe from the threat of pogroms. Nevertheless, they had to face up to the realities of living in a malaria-infested area with a harsh climate.

It was against this backdrop of economic and political upheaval that little Eliezer Guitel (who later married and became Zlaskine) was born in Jaffa on August 19, 1889.

Her parents were Naftali and Haya Guitel.

They gave their little daughter a very unusual boys’ name, hardly ever used for a girl. Some of us even had doubts about Eliezer’s gender, despite the fact that she is always listed as female in official records.

This raises the question of whether the girl’s parents might have wanted to name their child after Eliezer Ben-Yehouda, who devoted his life to promoting Hebrew as the everyday language of the Jews living in areas under Ottoman rule. Mr. Ben-Yehouda had lived in Jaffa for a while, seven years before Eliezer Guitel was born.

At some point, Eliezer Guitel left Palestine and emigrated to France. Whether she was alone or with her family, and when exactly she moved, we do not know. She lived in Paris, where she worked as a milliner. When she got married in 1916, during the First World War, she gave the same address as her fiancé. They were living at 20 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville, in the 4th district of Paris. Neither she nor her husband produced a birth certificate when they got married. She gave the number on her foreigner’s certificate and he gave his military service logbook. It’s interesting to note that the town hall registrar noted that “she does not know how to sign to her name”: Might she have been illiterate, or was she unable to write the Latin script?

There are also very few remaining traces of Eliezer’s husband, Isaac Zlaskine.

Isaac too was born in Palestine, in the city of Jerusalem, in 1897. We do not know when he emigrated to France. He was 8 years younger than Eliezer. When they got married on September 27, 1916, Eliezer was 27, but Isaac, at 19, was still a minor according to the French legislation of the time. He was a year too young to be drafted into the French army to serve in the war.

No relatives were present at the wedding, but the official record shows that neither of their mothers were working at the time, Eliezer’s father was dead, and Isaac’s father, Maurice (a French name!), was a tailor.

Isaac was a cabinet-maker and Eliezer was a milliner. Both were artisans, as were the four witnesses at the wedding: Geneviève Martin, 39, who lived at at 3 rue Cloche Perce (4th district of Paris), had no profession; Alice Gosselin, 36, who lived at 10 rue Aubry le Boucher (4th district of Paris), was a laundry worker; Marie Gaussé, née Rebrioux, 21, who lived at 3 rue de Jarente (4th district of Paris), was also a laundry worker; and finally Lipa Rainstein, 34, who lived at 19 rue de Charlemagne (4th district of Paris), was a chauffeur. Eliezer and Isaac both came from, and continued to live in, a humble artisan environment. They lived in the same Paris neighborhood as the witnesses to the wedding, who were presumably their friends. We found no further trace of the couple after they got married.

Eliezer et Isaac Zlaskine’s marriage certificate

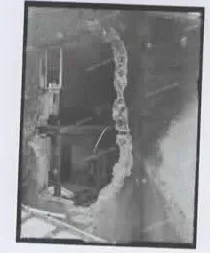

We do know, however, that the apartment building at 20 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville, where they were living when they got married, was damaged towards the end of the First World War. This was one of many long-range cannon bombardments carried out by the “Pariser Kanonen”, which were stationed about 70 miles from Paris, during what was known as the Ludendorf Offensive (March 21 – July 18, 1918).

Damage to 20 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville caused by cannon shelling on March 18, 1918.

Damage to 20 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville caused by cannon shelling on March 18, 1918.

Photograph(s) by Albert Moreau.

Source: https://imagesdefense.gouv.fr.

We then lose track of Isaac for good (despite having searched in the French civil, police and defense registers). He doesn’t appear to have died, since Eliezer was listed as married without children (rather than widowed or divorced) when she was arrested at the end of June 1944. After that, however, Isaac is not mentioned again on any records about Eliezer.

Nor is there any information available about Eliezer in the inter-war period. The Paris Police Headquarters archives include no record of her, even after the Security Branch opened a “central file” in 1934. There is no indication that she wanted to remain registered as a foreigner, nor that she applied to become a French citizen by naturalization. There is also no record of her having applied for a passport to travel abroad (to move back to Jaffa, for example).

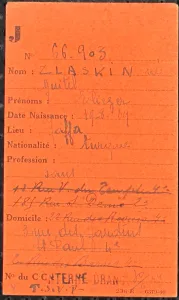

The next official trace of her was during the Second World War, when she was registered as a Jew as required by the Vichy regime, which was working in collaboration with the Germans. She was assigned the registration number 66903. None of the records about her include any reference to family members or close friends.

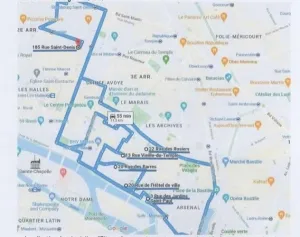

We had very little information to go on, but we do know that Eliezer had five different addresses in Paris during the war, all of them in the same area, between the 2nd and the 4th districts of Paris. They were:

- 13 rue Vieille du Temple in the 4th district

- 22 rue des Rosiers in the 4th district

- 3 rue des Jardins in St Paul, in the 4th district

- 20 rue des Barres in the 4th district

- 185 rue Saint Denis in the 2nd district: this is where she was arrested on June 30, 1944.

A map of the places where Eliezer lived at the time she got married and to which she moved during the war. Map produced using Google Maps

Until late spring 1944, she managed to avoid the roundups, although from October 1940 onwards she had to live with the restrictions introduced by the Vichy regime’s anti-Jewish legislation.

The main anti-Semitic policies of the Vichy regime and the German occupiers

- September 27, 1940: A German order calling for a census of Jews in the occupied zone and for Jewish stores and businesses to be identified. The deadline for the census was October 20, 1941. The census ended on the 19th and the Police Headquarters opened the “Fichier des Juifs” (Jewish File).

(At the end of September, a German census recorded 150,000 Jews in Paris, including 64,000 foreign Jews) - October 3, 1940: The Vichy government enacted a decree on the status of Jews in the free and occupied zones: from then on, French Jews were banned from working in many jobs in the public and private sectors.

- October 4, 1940: The Vichy regime enacted a decree on the status of foreign Jews: from then on, the French local authorities were given the power to intern foreign Jews or to place them under house arrest.

- October 7, 1940: The Vichy regime repealed the 1870 “Crémeux” decree, which had allowed Algerian Jews to become French citizens.

- From October 18 1940 to December 1941: A series of German decrees were issued. They covered the “Aryanization” of Jewish property, which stripped Jews of their businesses.

- March 29, 1941: At the request of the occupying forces, the Vichy government founded the Commissariat aux Questions Juives (Commission for Jewish Affairs). The Germans requested that the organization be created in order to coordinate the persecution of Jews throughout France: the aim was to prepare the ground for them to be deported soon afterwards.

- May 14, 1941: The French police carried out the first round-up in Paris, which became known as the “green ticket” roundup, named after a letter that the authorities sent to the people subject to arrest. It targeted 3,710 foreign Jewish men, most of whom were Polish, and stateless men.

- June 2, 1941: The Vichy government ordered a census of Jews in the both the Free zone and the Occupied zone. It also enacted the second decree on the status of the Jews, which increased the number of jobs that Jews were allowed to do in both the Free zone and the Occupied zone.

- July 22, 1941: The Vichy government issued a decree on the “Aryanization of financial/business assets”, which required Jewish businesses to be registered and barred Jews from all commercial and industrial occupations. As a result, Eliezer was no longer allowed to work as a milliner. This is why the official records list her as having “no profession”.

- From August 20 through 25, 1941: The French police carried out their second roundup in Paris and the Drancy internment camp was opened at Cité de la Muette, north of Paris, a site that had been used as a prison camp since the beginning of the war. From this point on, it became a transit camp for Jews prior to them being deported. The first internees arrived on August 20, in the wake of this major roundup.

- May 29, 1942: The Germans introduced the compulsory wearing of the yellow star for Jews over the age of 6 throughout the occupied zone.

- July 16-17, 1942: The Vel d’hiv roundup took place.

- November 11, 1942: The Germans occupied the whole of France.

- August 20, 1944: The fall of Vichy regime. All laws relating to the “Jewish race” were repealed.

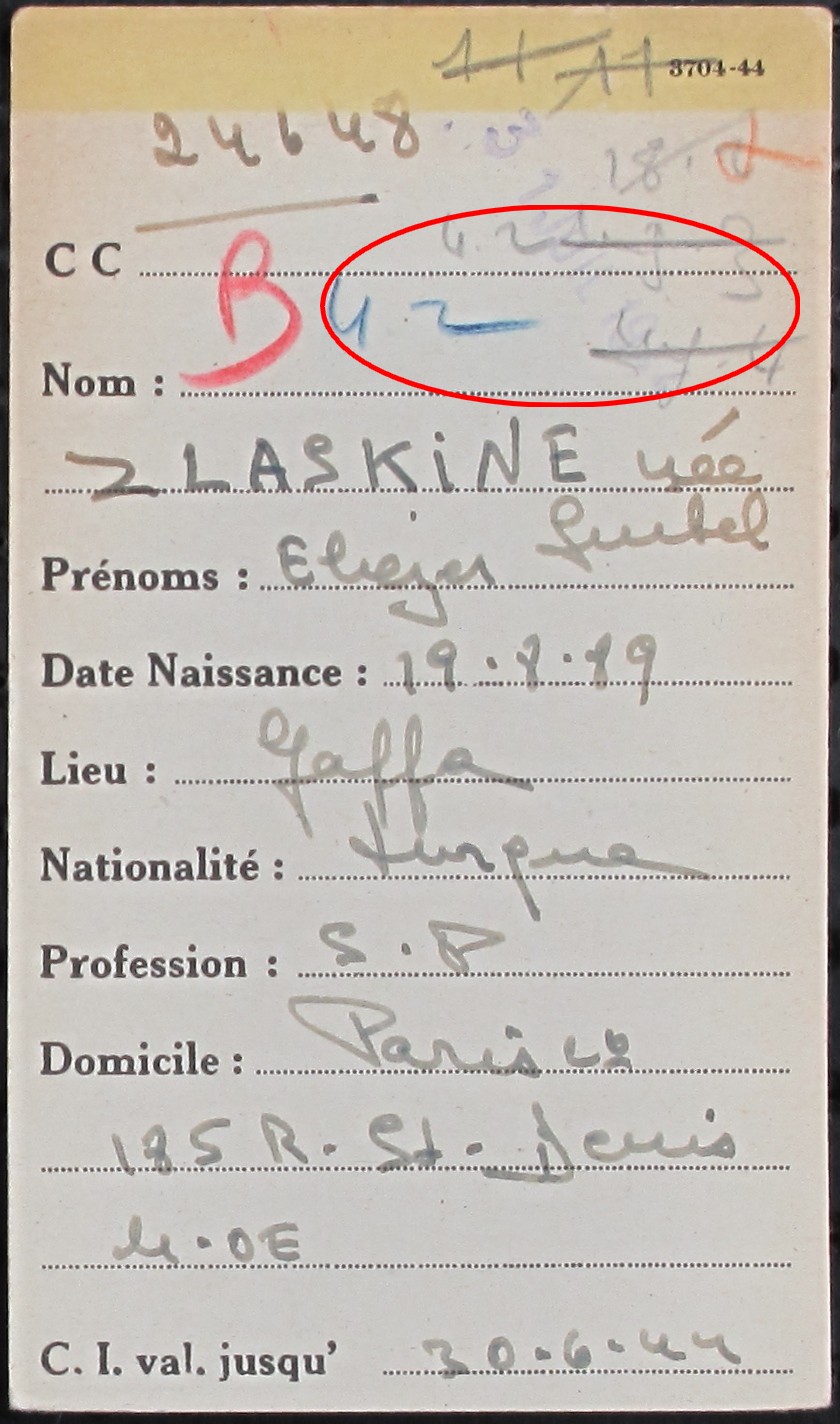

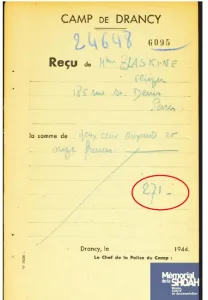

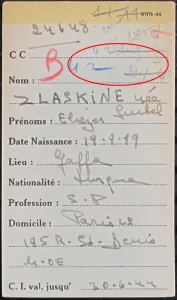

From the arrest register, we know that Eliezer was arrested at her home at 1am on June 30, 1944 and then taken to the Drancy internment camp, where she arrived at 2pm the same day. She was assigned registration number 24648.

The Drancy internment card bears the letter B, meaning that Eliezer was subject to immediate deportation.

When she arrived at Drancy, she had to hand over the 271 French francs that she had on her, as shown on the receipt below. This was the equivalent of around $55 today.

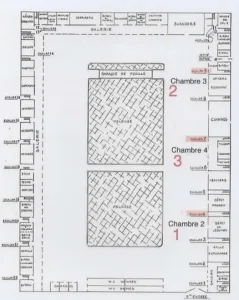

We were able to find out where she was placed during the month she was interned in Drancy, from June 30 to July 31, 1944: first on staircase 4, room 2, then on staircase 9, room 3, and lastly on staircase 7, room 4.

We have noted the places where Eliezer Zlaskine was interned from June 30 to July 31, 1944 on a plan of Drancy camp.

Shoah Memorial plan of Drancy camp, on which we have added the places where Eliezer Zlaskine was interned from June 30 to July 3, 1944.

Eliezer was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, on Convoy 77, which was the last of the large convoys from the Paris area. There were 1,306 people on board the drain. The French authorities later declared her to have died as soon as she arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944, which was just a few days before she would have turned 55.

Drancy: from “La cité de la Muette” housing development to a detention center

“La Cité de la Muette” in Drancy, which was designed in the 1930s, was originally intended to provide low-cost housing for local families. It was designed to provide the suburban low-income population with modern, hygienic accommodation. There were to be 1,250 apartments in total.

The developer ran into problems with the project (high rents, cramped conditions, faults, etc.), and it was still under construction when the war broke out. Occupied by German troops in June 1940, the site temporarily became a detention camp for French and British prisoners of war. The camp was enclosed by two barbed wire fences, with a pathway between them for camp guards.

On August 20, 1941, the Cité de la Muette became a transit camp for Jews who were to be deported. The first internees arrived on August 20, following the first major roundup in Paris, which took place from August 20 through 25, 1941. The first internees were 4,230 men, 1,500 of whom were French.

Although the Nazis oversaw the camp, the French military police (and the Seine department procurement service) were responsible for running it. The first convoy left Drancy for Auschwitz on March 27, 1942. Around a thousand Jews were deported that day. From July 1942 onwards, deportation convoys left one after another, averaging three a week. The night before a convoy was due to leave, the detainees were searched and anything of value was confiscated. A permanent sense of dread reigned over the camp.

In early summer 1944, as the Allied forces were advancing towards Paris, thousands of Jews were brought to Drancy from towns in the south of France in order to be deported.

From August 1941 to August 1944, over 63,000 Jews living in France were interned at the Drancy transit camp prior to being deported to the German Reich’s killing centers, in particular Auschwitz. The last large convoy of 1,306 people left for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. This, Convoy 77, was the one on which Eliezer Zlaskine was deported.

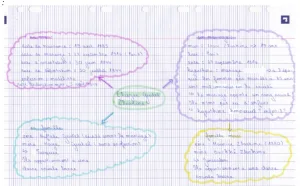

A biographical sketch of Eliezer Zlaskine’s life.

Eliezer Zlaskine, née Guitel is listed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

In addition to the documents provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, we contacted or referred to the following sources for further documentation:

- The French National Archives at Pierrefitte

- The Paris Police headquarters archives

- The City of Paris archives

- Yad Vashem

- The Shoah Memorial

We would like to thank:

The staff of the Shoah Memorial, who responded so kindly and efficiently to the students’ questions

The Convoy 77 non-profit organization, including Georges Mayer, Serge Jacubert, Claire Podetti and Sandrine Labeau, for their unfailing support over the past 2 years.

Sources :

- “Jaffa – port de Jérusalem au XIXe siècle” (Jaffa – the port of Jerusalem in the 19th century), Les Cahiers du judaïsme, spring-summer 2000, n°7

- Jean-Marie Delmaire, De Jaffa jusqu’en Galilée. Les premiers pionniers juifs (1882-1904) (From Jaffa to Galilee. The first Jewish pioneers (1882-1904)), Lille, Presses universitaires du Septentrion, coll. “Savoirs mieux”, 1999, 130 p.

- Dominique Perrin, Palestine, une terre, deux peuples, (Palestine, one land, two peoples) ed Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2000

Links :

- https://akadem.org/pour-commencer/histoire-de-la-shoah/la-shoah-en-france-21-03-2014-58305_4522.php

- https://irel.ephe.psl.eu/ressources-pedagogiques/comptes-rendus-ouvrages/jaffa-jusquen-galilee-premiers-pionniers-juifs-1882

- https://books.openedition.org/septentrion/48740?lang=fr

- https://www.carep-paris.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/YoussefCOURBAGE_Les-Juifs-dans-lEmpire-ottoman-jusqu%C3%A0-la-D%C3%A9claration-Balfour.pdf

- https://www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com/Les-Palestiniens-et-le-projet-sioniste.html

- https://www.lhistoire.fr/la-déclaration-balfour-et-les-juifs-de-lempire-ottoman

- https://www.histoire-immigration.fr/integration-et-xenophobie/enregistrer-et-identifier-les-etrangers-en-france-1880-1940

- https://www.france24.com/fr/20201003-il-y-a-80-ans-le-statut-des-juifs-en-france-un-premier-pas-vers-la-politique-du-pire

- https://www.enseigner-histoire-shoah.org/outils-et-ressources/fiches-thematiques/le-regime-de-vichy-et-les-juifs-1940-1944/la-politique-antisemite-des-allemands-et-du-gouvernement-de-vichy.html

- https://www.histoire-immigration.fr/caracteristiques-migratoires-selon-les-pays-d-origine/juifs-d-europe-orientale-et-centrale

- https://www.enseigner-histoire-shoah.org/outils-et-ressources/documents-darchives/persecutions-des-juifs-de-france.html

- https://www.yadvashem.org/fr/shoah/a-propos/declenchement-guerre-politique-anti-juive/france-et-belgique.html#narrative_info

- https://www.ajpn.org/commune-paris-en-1939-1945-75056.html

- https://lejournal.cnrs.fr/articles/rafle-du-vel-dhiv-nouvel-eclairage-sur-un-crime-francais

- https://garedeportation.bobigny.fr/104/les-etapes-de-la-deportation.htm

- https://www.paris.fr/pages/le-memorial-de-drancy-lieu-de-memoire-de-la-deportation-des-juifs-15426

- https://www.paris.fr/pages/le-memorial-de-drancy-lieu-de-memoire-de-la-deportation-des-juifs-15426

- https://monumentum.fr/camp-drancy-puis-cite-muette-pa93000015.html

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_de_Drancy

- https://drancy.memorialdelashoah.org/le-memorial-de-drancy/qui-sommes-nous/histoire-de-la-citede-la-muette.html

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/fr/article/drancyhttp://www.enseigner-histoire-shoah.org/outils-et-ressources/fiches-thematiques/le-regime-devichy-et-les-juifs-1940-1944/etude-de-cas-le-camp-de-drancy-1941-1944.html

- https://www.ajpn.org/internement-camp-de-drancy-67html

- https://www.fondationshoah.org/memoire/drancy-1941-1944-un-camp-aux-portes-de-paris-un-filmde-philippe-saada

- https://www.enseigner-histoire-shoah.org/outils-et-ressources/fiches-thematiques/le-regime-de-vichy-et-les-juifs-1940-1944/etude-de-cas-le-camp-de-drancy-1941-1944.html

- https://imagesdefense.gouv.fr/

Français

Français Polski

Polski