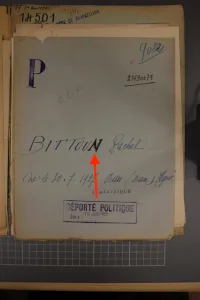

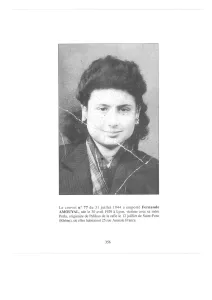

Rachel BITTOUM

A photograph of Rachel when she was 16 years old, kindly provided by her family

Rachel’s story

July 12, 1944: Rachel was arrested during a roundup in her neighborhood. She was taken to the Montluc jail in Lyon. From there, on July 24, she was transferred to Drancy camp, where she remained until July 31, 1944.

Rachel was recorded as having “disappeared” in the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland on August 5, 1944. In France in those days there was a 5-year waiting period before a “missing person” could be declared to have died.

We are a group of 9th grade students from the Jean Brunet secondary school in Avignon, in the Vaucluse department of France and we have been working on the Convoy 77 project throughout the school year. Rachel Bittoum was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. We researched her life story and then wrote her biography.

During the year before we began, another 9th grade class had already put a lot of work into gathering information about Rachel’s life.

Following in Rachel’s footsteps

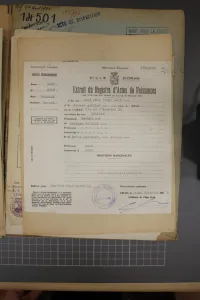

Rachel Bittoum was born in Oran, Algeria, on July 30, 1927. She is sometimes referred to as “Bittoun” in official documents. The spelling has been corrected, however, in the file held by the French Defense Historical Service.

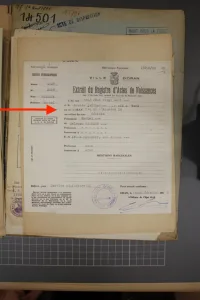

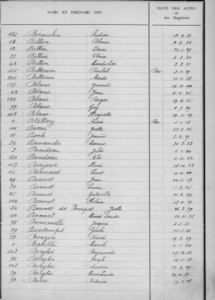

Rachel Bittoum’s birth certificate

Rachel’s mother, Aicha Karsenty, was born in Nedrema, Algeria, on June 30, 1901. The town of Nedroma, or Nedrema, is in the west of the country, close to the Moroccan border, about 36 miles northwest of Tlemcen. Aicha’s family may have emigrated from Spain at some point, as this is a name that was quite common in Spain according to our research. Aicha’s parents were Mimoun Karsenty and Matra Giezelan/Giezilan, sometimes spelled Maha Ghozelan.

Aicha’s father, Salomon Bittoum was born in Demnate in Morocco in 1893. His parents were David Bittoum Marion/Mariem Zagoreri.

Photo of Salomon Bittoum, Rachel’s father

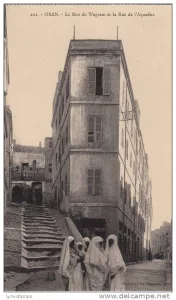

Aicha and Salomon met in Oran and set up home there at 3 rue de l’Aqueduc. This is where Rachel was born.

Shortly after Rachael was born, in July, the family moved to Saint Fons, a suburb of Lyon in the Rhône department of France. On the following French civil status record, the word “rec” was entered in front of her name on November 3, 1927.

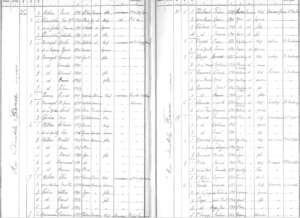

Source: Rhône departmental archives

Their first home in Lyon was at 47 avenue Jean Jaurès. Aicha became known as Alice Bittoum shortly after she arrived in France. They were married in a civil ceremony in France on February 7, 1931, but might they have previously been married in a religious ceremony in Algeria?

Turn-of-the-century postcard of rue de l’Aqueduc in Oran

1930s postcard of avenue Jean-Jaurès in Saint-Fons

Salomon and Aicha’s marriage certificate

The reason they chose Saint-Fons and what their life there was like

Our research revealed that during the First World War, France did not have enough manpower to keep the factories running, so it had to bring in laborers from the French colonies and other countries. The Saint-Fons town hall kindly provided us with some further information about the town and how and why so many Moroccan Jews settled there. In the 19th century, Saint-Fons was a little village south-east of Lyon, where silk manufacturers from the city set up workshops on the banks of the Rhône. Dye manufacturers in particular were keen to move to Saint Fons, which became a key location for the chemical industry. Since they needed a large workforce, immigrants were welcomed in Saint Fons and it was especially popular with Jews from Morocco. They often spoke little French when they first arrived.

After that, other people moved in, and were offered both jobs and accommodation. The men were employed by Pommerol, Bâle, Rhône-Poulenc and Saint-Gobain, amonth others. They often lived in low-income housing.

Salomon was Moroccan, but Aicha and her children were already French citizens: we discovered that Algerian Jews had been granted citizenship according to a decree dated October 24, 1870, known as the Crémieux Decree. However, when the Crémieux decree was repealed on October 7, 1940, the French Jewish population living in Algeria lost their French nationality. It was only on October 21, 1943, almost a year after the Allied landings in Algeria, that this decision was revoked.

According to their marriage certificate and the 1936 census of Saint-Fons, Salomon was initially a “laborer” and later became a “foreman”. The census lists 8 families living at no. 25, including the Amouyal family, who lived on the “courtyard” side of the building. By this time, Rachel had some brothers and sisters: Marie (1928), David (1930), Raymond (1931) and Maurice (1934). Later on came Juliette (1936), Simon (1938), Angèle and Etoile (1940) and Claudette (1945), who Rachel never met. Laurette Marcatel, who was Juliette’s daughter and thus Rachel’s niece, told us that life was tough for them in the apartment at 25 rue Anatole France. However, all the families in Saint Fons knew each other and everyone had aunts, uncles and cousins on the same street.

Screenshot of the page for 25 rue Anatole France from the 1936 census of Saint-Fons

Source: Rhône departmental archives

In November 2022, we went on a three-day trip to Lyon: there were fourteen of us and three teachers. We wanted to visit some of the key sites in the history of deportation in France, and some of the places where round-ups took place.

On the first day, we went on a guided tour of the city from Croix Rousse to Bellecour, exploring the history of the Resistance and the Deportation. Jean, from the Lyon Resistance and Deportation Historical Center, was our guide. In the evening, we went to see Olivier Dahan’s film about Simone Veil, “Le voyage du siècle” (“The journey of the century”).

The following day we went to the Maison d’Izieu, (a memorial museum on the site of a former children’s home from which children were deported) in the Ain department of France, about 45 miles from Lyon.

The house at Izieu was a refuge and summer camp for children during the war. Many of the children staying there were Jewish, and on 6 April 1944, Klaus Barbie had them rounded up. We visited the house itself and the museum next door, where we learned a lot about Klaus Barbie and his awful crimes.

In the morning we took part in workshops about the Vichy government’s anti-Semitic policies, Drancy camp and Auschwitz.

In the Memorial museum, there was a big book by Serge Klarsfeld called Le Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Deportation of the Jews from France), and we discovered that another girl who was deported on Convoy 77, Fernande Amouyal, lived at the same address as Rachel. We took photos of some books so that we could study them in class when we got home.

When Rachel was rounded up, July 12, 1944

According to various records, the Gestapo carried out a roundup in Rachel’s neighborhood on July 12, 1944, during which she was arrested. At the time, she was training to become a dressmaker at the Home Economics training center on Place Michel Perret in Saint-Fons.

Class photo taken at the Home Economics training school. Rachel is on the top row, second from the right, wearing glasses

Rachel was alone when she was deported; Aicha, her mother, later wrote in one of her witness statements “My daughter was arrested at our home”.

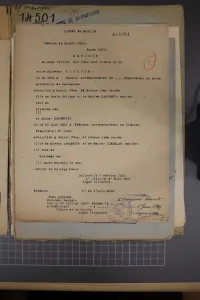

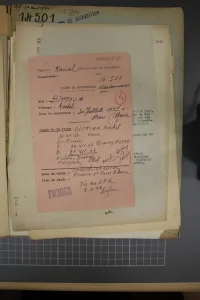

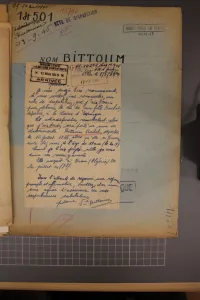

Research record

Mr. Benssoussan’s witness statement

During our research, we came across Rachel’s family tree online. Our teacher contacted Laurette Marcatel, the person who had published the tree. She is Rachel’s niece. Her mother, Juliette Bittoum, was Rachel’s sister. Ms Marcatel told us that her mother told her that Rachel was alone when she was rounded up because Juliette was in a sanatorium at the time. All the children except Rachel went to visit her. There was also a witness to the roundup, a Mr. Bensoussan. One of the records reads “Roundup of all Jews in the neighborhood, outside and in their homes, July 12, 1944”.

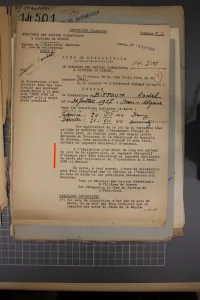

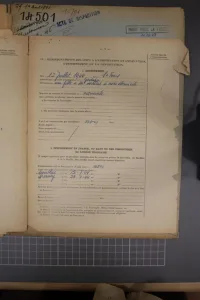

Application form for the attribution of the status of political deportee

We had already noticed in Serge Klarsfeld’s Memorial list that Fernande Amouyal, Rachel’s neighbor, was also rounded up on July 12, at the same time as Rachel. Her mother, Perla, was arrested too. We can only hope that Rachel managed to meet up with them so that she was not alone. Fernande Amouyal’s biography on Convoy 77 website says reads: “Alone at home with her mother, they were arrested by a couple called Goetzmann and Benamara, who were Gestapo agents, in full view of their neighbors, Maria Ribeiro and Lucie Verelle”.

Goetzmann and Benamara couple

The Saint-Fons town hall kindly provided us with a file which states that the Goetzmann and Benamara couple were there at the time of the arrest and another file written by a keen local historian, Claude Delmas. There is also some more information about the Amouyal family.

“Goetzmann and Benamara, with the help of an accomplice, Ben Selmi, and some female informers, terrorized the commune, making a number of arrests on behalf of the German Gestapo. The couple were responsible for 23 such missions which resulted in 66 arrests: 48 people were deported, 36 died, some of whom were executed but most of whom were deported to extermination camps. And all for a few thousand francs. Most of the people were Jews from Saint-Fons”.

Information from Saint Fons town hall about people who were deported from the town

Joseph Bensoussan testified that Rachel travelled with him in the prison truck that took them to the Fort Montluc jail.

Joseph Benssoussan’s witness statement

Internment in Montluc

In November, we also visited the former Gestapo headquarters (CHRD). We then went on to visit the Memorial museum at Montluc jail, where Rachel was interned. The cells were very small, only about 16 square feet, and they were used to hold up to eight people.

Photos of Montluc jail

From Montluc to Drancy

Mr. Bensoussan, who travelled to Montluc with Rachel, was also taken to Drancy with her and states that she was then sent to “Germany”. Another witness was Nina Chriqui, a 35-year-old shopkeeper from Place des Terreaux in Lyon, who was arrested on June 23. She stated that she saw Rachel in Drancy, that Rachel arrived after she did, that she knew that Rachel was “from St. Fons” and that Rachel was then sent to an extermination camp, after which she never saw her again. Rachel was in Drancy when she turned 17, on July 30, 1944. The very next day, she was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77.

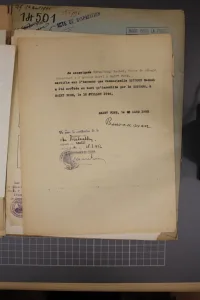

Nina Chriqui’s witness statement dated March 7, 1951

After the war

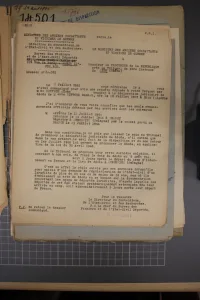

An certificate confirming that Rachel was missing was issued on September 18, 1946. On June 8, 1949, the Ministry and the Director of Civil Status and Research received a second copy of Rachel’s missing person’s certificate, which was addressed to Madame Bittoum, a widow. Salomon Bittoum had died in 1946, according to a record in the Rhône departmental archives. Some records also show that his wife referred to herself as “Mrs. widow of Bittoum”.

In 1951, Rachel’s mother applied to the police department to have the reason for Rachel’s arrest officially acknowledged, given that she was Jewish but had not been a member of the Resistance. On the “Application for the status of political deportee” form, the authorities wrote on Aicha’s behalf: “I presume that my daughter was arrested and interned because she was a Jew”.

On June 10, 1953, Rachel was deemed to have been “a political deportee”, (meaning that she was deported for political reasons), and the Lyon court issued judgment pronouncing her dead, which was sent to Saint-Fons on November 23, 1953. Her mother did everything in her power to prove her that her daughter had died, citing the French state as a witness.

In France, anyone who went missing in France, whether their body was found or not, was declared to have died. The French state therefore declared that Rachel was dead because her body was never found. When people were deported and did not come back, the French authorities estimated how long the deportation and transport had taken, and from that determined a probable death date. The following report from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War states: “In my opinion, the date should be August 5, 1944, i.e. 5 days after departure from the internment camp in France, and the place of death should be Auschwitz (Poland). This is in fact the rule that my department follows when it receives a request to establish the civil status of a Jewish person who was over 55 or under 14 years of age, in which case it issues a death certificate based on documentation relating to the camps for Jewish deportees, according to which deportees of those ages were systematically exterminated as soon as they arrived at the camp, i.e. approximately 5 days after their departure from France”. The exact date on which Rachel died is therefore unknown.

When we got back from our trip to Lyon, we made a series of recordings about people who were victims of prejudice. We called our podcast “Ne fermez pas les yeux ! Un podcast du Collège Jean Brunet” (“Don’t close your eyes! A podcast from Jean Brunet junior high school”). We also planted a cherry tree in memory of the victims.

The project and our trip will remain etched in our memories forever: it was a dark chapter in our history. It’s something unforgettable and deeply moving. It took us beyond our everyday lives and enabled us to carry out an investigation. We will also never forget the time we spent together: learning everything we now know together; not just having the impression of doing school work, but also being involved in activities that helped us to move forward in our lives, and to learn. It was a landmark year for all of us, and we’re proud to have had the opportunity to research Rachel Bittoum’s life, the history of what happened and the realities of life during the Second World War.

Français

Français Polski

Polski