Esther SMOLAR, née FELDA (1897-1944)

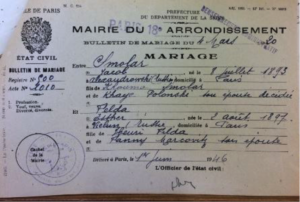

Esther Felda was a Russian-born Jewish woman. She was born in 1897, in Vielun, a town in Poland, which at that time was part of the Russian Empire. Her parents were Henri Felda and Fanny Marcovitz. We do not know how old she was when she arrived in France, but we do know that on March 3, 1920, in Paris, she married Jacob Smolar, who was also Jewish and born in Russia. Did Esther meet her husband-to-be in Russia, or in Paris? When exactly did she move to France? We do not know. However, her parents attended the wedding, so our best guess is that the Felda family emigrated to France when she was still quite young. Did they move to France in order to flee the widespread anti-Semitic pogroms that had begun sweeping across Eastern Europe and Russia at the turn of the 20th century? Were they perhaps fine folk or wealthy landowners who fled the Russian Empire after the Bolshevik revolution in 1917? There is nothing in the archives to suggest this, but such events may well have been what drove them into exile.

Esther and her husband Jacob set up home in Paris and, in 1921, had a daughter, Ginette. The family lived at 28 rue des Boulets in the 11th district, in a Haussmann-style building not far from Place de la Nation. Esther had a salaried job, and her husband was a tailor. According to the records, Esther acquired French nationality when she married Jacob. Between the wars, they lived their lives as a typical French immigrant family as they raised Ginette. Like many of their contemporaries, they must have spoken French during the day but probably continued to speak another language at home, perhaps Russian or Yiddish, the Jewish dialect spoken by the Jewish community in Eastern Europe.

Jacob Smolar and Esther Felda’s marriage certificate, dated March 4, 1920. It was sent to Ginette Smolar on June 1, 1946, when she was putting together a missing persons’ application.

Source: Smolar Jacob, French Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier n°21P539707.

Esther lived through the outbreak of war in 1939 and, after France was defeated in 1940, the German Occupation. She watched on as Marshal Pétain came to power and made France an authoritarian, anti-Semitic state. In 1940, the Vichy regime passed a series of decrees known as the Status of the Jews, which discriminated against Jewish people and barred them from working in certain professions, such as doctors, lawyers, factory managers and school principals. While Esther, as an employee, was not affected by the employment legislation, she was soon affected by several other policies, such as the census of the Jewish population and its assets, in 1941, and the requirement to wear the yellow star introduced in 1942.

Ether, Jacob and Ginette also lived through the horror of the Vel d’Hiv roundup, during which over 4,000 French police officers scoured the streets of Paris and the surrounding area arresting Jews – over 13,000 in all, including 4,000 children, and took them to the Velodrome d’Hiver (Winter Cycling track). What did the Smolar family do during this time? Did they take part in the census and register themselves as Jews? Did they wear the yellow star? Or did they go into hiding, for fear of being arrested and deported? Were they aware that the Jews in Paris were arrested as part of Hitler’s “Final Solution” in 1942? What must Esther have thought about it all? How did she feel? She must have been afraid not only for herself, for also her husband and especially for her daughter, Ginette. In response to all these questions, our best guess is that Esther and her family went into hiding to avoid the Nazi threat. This is borne out by the fact that the records state that Esther and her husband were arrested by the French militia following a tip-off. They were captured in their apartment, so we can only surmise that they had not registered themselves as Jews but nevertheless continued to live at home.

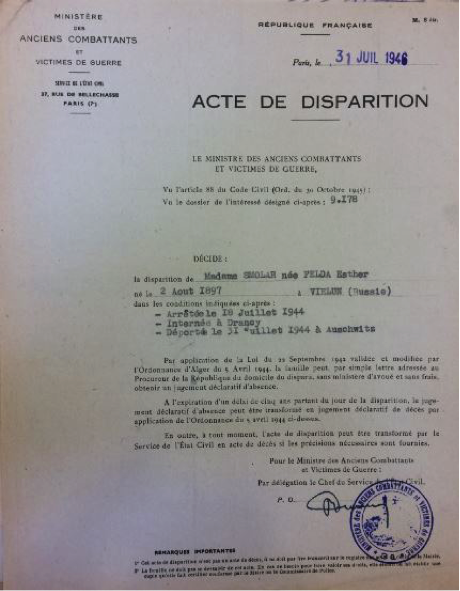

Esther and her husband were arrested on July 18, 1944, just over a month after the Allies had landed in Normandy on June 6. We can imagine her optimism as the Allies steadily advanced towards Paris. The Germans, however, hell-bent on continuing their murderous rampage, stepped up their hunt for Jews in 1944, which served as further proof of their intent to commit genocide. Esther and her husband were among the last people deported from France to the death camps in the summer of 1944. On July 19, they were taken to Drancy internment camp, north of Paris, the main departure point for trains bound for Germany and Poland. On July 31, they were loaded onto Convoy 77 and deported to Auschwitz. The French Ministry of Veterans Affairs estimated that the journey took five days, although we now know that the convoy arrived in Auschwitz on August 3. We can only imagine how they must have felt that day: exhausted, after the long journey locked in a cattle car, with hardly any food or water, no toilets, crammed in with dozens of other deportees, all utterly dehumanized. Then came the selection, during which the Nazis sorted people into lines: the younger, fitter people who would be sent into the camp for forced labor and the those who would be sent to the gas chambers and murdered immediately. Children under the age of 14 and anyone over the age of 50 were always selected for execution. Esther was 47 years old at the time, and Jacob 51. Were they separated for the final time, there on the ramp? Or were they executed together, as soon as they arrived? Either way, they never came back from Auschwitz, where they were murdered by the Nazis.

In 1946, over a year after France was liberated, Esther and Jacob’s daughter Ginette applied to the public prosecutor of the Seine department for a court ruling confirming that her parents were still missing. For some reason, she was not arrested at the same time as her parents. She was 21 years old at the time, so she may have been living elsewhere by then, or perhaps she was simply not at home that day. In common with so many other people in the immediate aftermath of the War, she must have worried about what had become of her parents: had they simply been deported? Perhaps they would be repatriated, but that would take time, as the war had wrought so much destruction. Along with the rest of the population, she must have seen the photos of the concentration camps, and followed the news reports about the Nuremberg trials (1945-1946), yes still she did not know what had become of her parents.

Ultimately, in accordance with a French decree issued in 1946, which stated that if there was no news of a deported person five years after they went missing, they were to be declared dead, Esther and Jacob were pronounced dead in 1950. Their official date of death was August 5, 1944.

This biography is based on records from the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy: Smolar Jacob, dossier n°21P539707.

Missing person’s certificate in the name of Esther Felda, issued on July 31, 1946 by the French Ministry for Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War

This then, is how Esther Smolar’s story fits into the history of the Occupation and the Holocaust. In all, some 135,000 people were deported from France to camps and killing centers in Germany and Poland. Of these, around 60,000 were deported as a result of repression (resistance fighters, political opponents, communists, etc.) and around 75,000 simply because they were Jews. Of these Jews, only 3.5% survived, and nearly 60%, including Jacob and Esther, were murdered as soon as they arrived in the camps.

Français

Français Polski

Polski