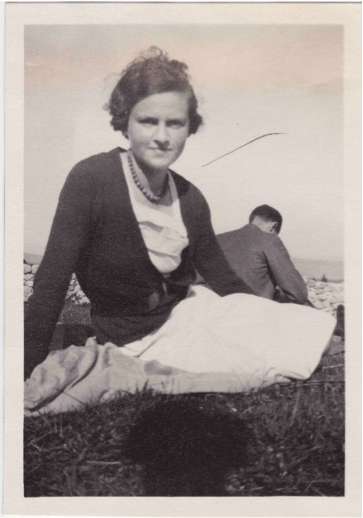

Gilberte REHNS

This project was carried out by a group of 9th grade students at the Victor Duruy middle school in Châlons-en-Champagne, in the Marne department of France. They volunteered to work on it in their spare time, with the guidance of their history and geography teacher. The six students, who had been made aware of the importance of remembering the Holocaust through a cross-disciplinary practical program called “Chemins de mémoire” (“Pathways of Remembrance”), focused on a family group who were deported together, the Rehns family: Georges, Sarah and Gilberte.

Starting in February, the group met for 2 hours every other week and began going through the records provided by the Convoy 77 team. The students worked in pairs on each member of the family, and they soon began to wonder whether there were any surviving descendants of this family, given that Gilberte had a brother and a sister. They trawled the Internet using official websites such as those of the Shoah Memorial and Yad Vashem, as well as genealogy sites, and were soon able to draw up a family tree of the Rehns family’s ancestors and descendants, including their daughter, Andrée Bodenheimer.

They discovered that both of his daughters had been married. The first, Nadine, was married to a Mr. Lefort des Ylouses, while the second, Anne-Marie, was married to a Mr. Duval. As one surname is more common than the other, they started looking for descendants of the “Lefort des Ylouses” family on the Internet and came across “Juliette Lefort des Ylouses”, to whom they wrote a letter on March 7, 2023, although they were unsure if the mailing address that they had for her was correct. On March 15, we received a reply by email, and we had indeed made contact with the descendants of the Rehns family! After several e-mail messages, Mrs. Nadine Lefort des Ylouses (Juliette’s grandmother and Georges and Sarah’s granddaughter) was keen to speak with the six students, and we arranged a videoconference on April 14. The students had their questions ready in advance and during the discussion they were able to expand their knowledge about the Rehns family. Mrs. Lefort kindly sent us some photos, together with the book she had written about her family for her children, thus providing us with reliable and accurate information.

When our research was completed at the beginning of July, I sent it to Mrs. Lefort for review and to ask her permission to share it with the Convoy 77 project. She replied: “I have just read all the material you sent me, and I would like not only to give you my approval, but also to congratulate you (and your students) on the marvelous work you have accomplished”.

Sadly, Mrs. Lefort passed away at the end of August. However, my students and I are happy to have contributed to preserving the memory of her family through this project, and we feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to meet her and talk with her.

Cécile Boudes

1) Before the war

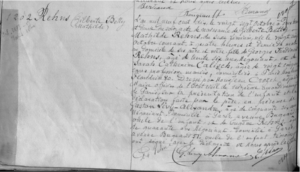

My name is Gilberte, Betty, Mathilde Rehns and I was born on October 25, 1910 in the 16th district of Paris.

I had an older sister, Andrée and a younger brother, Jacques.

I lived with my parents, Georges and Sarah Rehns, at 80 boulevard Flandrin in the 16ème district of Paris, because I was not married. In our social circle, it was frowned upon for single young women to live on their own if they were not married.

Gilberte Rehns’ birth certificate

My parents and I led a luxurious lifestyle, but we were also discreet and unassuming. My parents were keen mountaineers and went on long-distance cruises.

Once a year, they took us all on vacation: it became a family tradition, and every summer they rented us a house by the sea in Saint Briac in Brittany, where we spent our vacations together.

I was very close to my sister Andrée, who was married to André Bodenheimer and to their two girls, my nieces, Nadine an Anne-Marie. We were a close-knit family and enjoyed spending time with our cousins.

Before the war, that was the kind of life my family led, both interesting and privileged. We had always been part of the French Jewish community who saw ourselves first and foremost as French. For us, religion was secondary. French Jews felt no real sense of solidarity with foreign Jews who had recently been naturalized as French citizens. My parents had great faith in France. They were deeply convinced that “France was our country”, and they were unaware of the danger that we were facing.

2) During the war

During the exodus from Paris, our family sought refuge in Bagnoles-de-l’Orne, a little town in Lower Normandy, where we had friends. My brother, my sister Andrée, her two little daughters and me spent a year in a house that my parents had rented. Andrée’s mother-in law, Hedwige Bodenheimer, came to stay with us, as did her husband André after he was demobilized.

Then we returned to Paris, but my father was no longer allowed to run his business “Les parfums Violet”. We lived in constant fear; I jumped at every ring of the doorbell, and at every sound, scared of being arrested. Living like that wears people down; we could not trust anyone or rely on anything, and we had to lie all the time. We were all very tense and never able to relax.

There were two occasions on which we could have left France, either to go to stay with my maternal aunt, Elise, who lived in London, or with some friends of my sister in the USA, but my parents, who were getting on in years and unaware of the danger they were putting us all in, were unwilling to change their ways, so we all stayed put in Paris, at 80 boulevard Flandrin.

As of June 1942, we had to wear a yellow star sewn onto our clothes, which we had to buy with our ration coupons. We were obliged to follow the rules set out by the Vichy regime and the Germans: we were not allowed to go out except at specific, limited times, even to go shopping or to see or medical check-ups; we were banned from going to the movies or listening to the radio, and we were forbidden from going to public parks and gardens.

Fortunately, I was able to make myself useful to the UGIF, the Union Générale des Israélites de France (General Union of French Jews). It was thanks to my sister’s friendship with André Baur, who founded the UGIF, that I was able to help needy families and lone children, and that might also have been why we remained safe for most of the war.

3) Arrest and deportation

After the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, as the Allied troops were advancing towards Paris, my parents (whom I refused to leave) and I were arrested at our apartment on July 19. We were taken to Drancy camp and then deported to Auschwitz on the very last transport, Convoy 77, on July 31, 1944

The Nazis sent me and my parents to the gas chambers as soon as we arrived in Auschwitz. We had no hope of surviving.

9th grade students Zoé Humblot and Valentina Labernia San Miguel

All the photos were provided by Nadine Lefort des Ylouses, Georges and Sarah Rehns’ granddaughter, together with the book, “Yesterday and Now”, which she wrote for her family. She also kindly gave us permission to publish them here on the Convoy 77 website.

In April 2023, the students had the opportunity to speak with Mrs. Lefort des Ylouses during a video call, and also to ask her questions to help them expand their knowledge about the family.

- Photo of Boulevard Flandrin: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:80-82_boulevard_Flandrin.jpg

- Shoah Memorial website: https://www.memorialdelashoah.org/

- Memorial resources: http://www.enseigner-histoire-shoah.org/outils-et-ressources/documents-darchives/persecutions-des-juifs-de-france.html

- Photo of the Violet Perfume factory: https://www.maisonviolet.com/pages/la-maison

Français

Français Polski

Polski