Gitla SEEUWS, née ZYLBERBERG (1898-1944)

“Happy as God in France”?

Gitla Zylberberg was born on June 24, 1898 in Brzeziny, Poland. Her parents were Akzyk Zylberberg and Hinda Dobra Tuszynski.

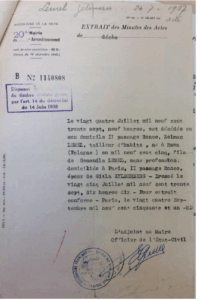

On October 29, 1929, in her hometown of Brzeziny, Gitla married Zelman Lemel, a tailor who was born in 1905 in Rawa Mazowiecka, in central Poland. They already had a daughter, Beila/Bejla, who was born on May 25, 1929.

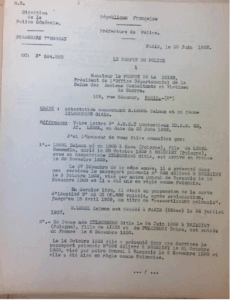

Identity certificate issued by the Paris Police Headquarters, which includes Gitla and Zelman’s marriage details. File on Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 537 780 -29

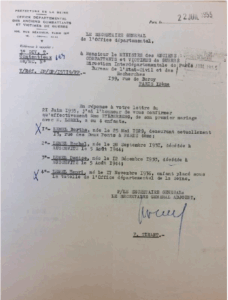

Certificate confirming the Lemel’s marriage and the birth of their children. File on Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 537 780 -42.

On November 29, 1929, a month to the day after the wedding, Zelman, carrying a Polish passport with a valid visa, arrived in France. It had been an official marriage, most likely arranged with emigration in mind, although they may have previously been married in a religious ceremony, which was generally considered acceptable within the Jewish community in Poland. In 1929, in the aftermath of the terrible Spanish flu epidemic, France was seeking immigrant workers to rebuild the country after the First World War. To encourage people to migrate to France, a law enacted on August 10, 1927 had facilitated access to French nationality.

We can safely assume that the Gitla and Zelman moved to France in search a better standard of living, while at the same time fleeing both the poverty and the increasing anti-Semitism in Poland, spearheaded by the Polish nationalists. As soon as Poland regained its independence in 1918, their leader, Roman Dmowski, declared: “In Poland, we have a quarter of all the Jews in the world. They make up 10% of our population and, in my opinion, this is at least 8% too high”1

Anti-Semitism thus played a key role in the Polish nationalists’ political vision, and plagued Polish political life in the post-war years.

The Eastern European Jews saw France as a welcoming, tolerant place, which had not only been the first country to emancipate the Jews in 1791 but had also vindicated Captain Dreyfus in 1906.

Gitla arrived a year or so after Zelman, on December 6, 1930, together with their daughter. She too arrived legally.

There is a Yiddish proverb that translates as “Happy as God in France”. Would this turn out to be true for Gitla, Zelman and Beila?

The family set up home Paris. According the 1931 census, they were then living at 12, passage des Ronces in Belleville, a working-class neighborhood in the 20th district of the capital. The area was home to large numbers of migrants from all over the world, and poor Polish Jews were able to find low-cost accommodation there. The Yiddish language rang loud in the streets, but the children went to the local schools, where they had to speak French, even if they continued to speak Yiddish at home with their parents. We do not know if, or how well, Gitla learned the French language.

The other Lemel children were all born in the French capital: First came Rachel, on September 28, 1931, then Denise on December 12,1933 and lastly Henri, on November 17, 1936, all in the 12th district of Paris. The girls went to the elementary school on rue Etienne-Dolet, where Beila began using the French version of her name, Berthe.

But then, disaster struck. Soon after Henri was born, the family met with its first tragedy since arriving in France. At 10:10 a.m. on July 24, 1937, Zelman died of uremia. His brother-in-law, David Morawiecki, a painter and decorator, went to declare the death.

Gitla, at the age of 39, suddenly found herself a widow, alone with four children to support and no income.

There is file in her name, dating back to 1937, from the Police Headquarters in Paris. It had been taken by the Germans when they retreated from France and later recovered by the Russians. (French National Archives, Moscow collection, ref. 19990488/91).

Zelman’s death certificate. File on Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-537-780-39

Remarriage in the midst of the persecution

After 1937, there is a gap in the records, and the next trace we found of Gitla was in 1942.

A form dated March 1955 notes that Gitla had been in hospital since July 15, 1942 (the date of the Vel d’Hiv round-up). It also says: “GF Pref. racial grounds”. Did the police go to her home to arrest her during the Paris roundup? The address given is passage Ronce, still at number 11, where she lived before she was married. Shortly afterwards, Gitla got married again.

The anti-Semitic crackdown had been gathering pace since 1940, and by the end of 1941, the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” had been agreed. On January 20, 1942, the order was given to destroy every last Jew in Europe. For French Jews, the situation became untenable.

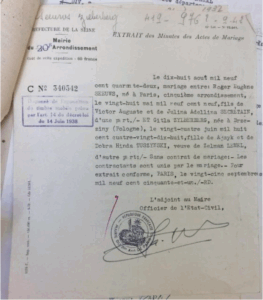

It was amid this extremely tense atmosphere, when Jewish people were simply trying to survive, that on August 18, 1942, Gitla married Roger Eugène Seeuws, who was born on May 28, 1909, in the 5th district of Paris. They had been neighbors since at least 1937 when, according to an electoral registration form for the 20th district, he was living at 12, passage des Ronces, in what was probably a very cheap hotel or boarding house.

A list of French prisoners of war issued by the German army on January 29, 1941 includes 2nd class Private Roger Seeuws of the 6th nursing platoon. He was being held in Stalag IX-A in Hohenstein, Germany at the time. He returned to Paris on January 29, 1941.

Did he escape? Or was he released, and if so, why?[i] Was he sick, or released during an exchange of prisoners of war for STO (Compulsory Work Service) “volunteers”?

Gitla and Roger Seeuws’ marriage certificate

File on Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-537-780-38

Roger Seeuws, who worked on roofs and chimneys, was the son of Victor Auguste and Julina Adellina Secretain. The fact that after the war he made only one request for information about Gitla (in March 1946, see below) suggests that it may have been a “marriage of convenience”, which would have enabled Gitla to become naturalized as a French citizen, thus providing greater protection for her children. We have been unable to verify this, but the reason we believe this may have been the case is that a law introduced by the Vichy government’s Minister of Justice, Raphaël Alibert, passed on July 22, 1940, had made naturalization much more difficult. The Vichy regime, as part of its wide-ranging anti-Semitic policy, did everything in its power to prevent Jews from becoming French citizens. Worse still, some Jews who had been naturalized after 1927 were even stripped of their French nationality, as were their French-born children. The three Lemel children born in France had been declared French citizens by the Justice of the Peace for the 20th district of Paris.

Gitla may well have believed that marrying Roger Seeuws, a non-Jewish Frenchman, would mean that she and her children would not be deported. Her son Henri, who was only a toddler when war broke out, agreed: “My mother remarried, I don’t know when; I think she remarried purely to obtain French nationality, in the hope of keeping us safe. I know I saw this man again once, when I was very young; Berthe needed to see him, I happened to be in Paris at the time, and she took me to see him in hospital. […] Since then, I’ve never heard a word about him”3

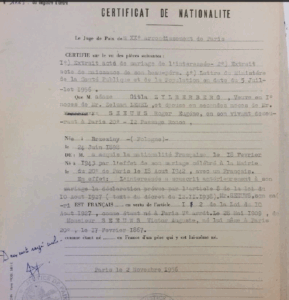

However, marrying a Frenchman and thus becoming a French citizen on February 18, 1943, was not in itself enough to save Gitla. As far as we know, she was never actually granted French nationality during her lifetime.

Anyway, it was then that the Lemel family moved. Mrs. Magny, the concierge at 12, passage Ronce, testified on December 16, 1946 that the Lemels had lived at number 11 “in the same passage Ronce” from 1935 to 1942. They were arrested, however, at number 12, where Roger Seeuws had been living before the wedding.

Certificate of French nationality (issued posthumously)

File on Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-537-780-33

During the Occupation, Gitla Zylberberg fell victim to anti-Semitic persecution by the Vichy regime and the Nazi occupiers. The Gestapo arrested her in Paris on grounds of her “race”.

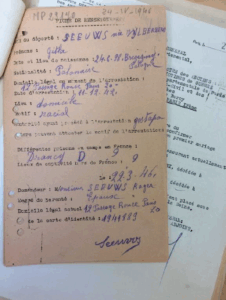

Request for information made by Roger Seeuws in 1946

File on Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-537-780-41

This form, sent to Roger Seeuws following his request for information, reveals that Gitla was arrested at their home, 12, passage des Ronces, on December 11, 1942, because, according to the criteria defined by the Nazis and the Vichy regime, she was a Jew, which is why it states that she was arrested “on racial grounds”.

The first time Gitla was arrested

While the records we have are inconsistent as to the dates of Gitla’s arrest and arrival in Drancy, December 16 is the most plausible date.

It was Gestapo that went to arrest her. On December 16, she arrived in Drancy camp, north of Paris. A Paris police register states that at 2 p.m. on December 16, Gitla, Denise and Rachel, who had arrested by the “judicial police”, were brought in (probably to Paris Police depot APP CC2-3 depot; December 16, 1942)[ii]. They left at 4:30 p.m. the same day, and were taken to Drancy. A neighbor was taking care of Henri at the time4 and thus he narrowly escaped being arrested.

A large number of Jewish people were arrested that day in the 20th district, and they too were sent to Drancy. Were the Lemel family victims of a roundup?

The three girls were most likely arrested together with their mother. However, the dates on the various records do not match. Some list the date of arrest as December 11, but one record from the French National Archives lists Gitla’s arrest date as December 16, 1942, while the Beaune-la-Rolande internment records for the three girls list the date as December 15, 1942. The Drancy records, meanwhile, again list the date as December 16. This is also the date used in official post-war documentation.

In the dossiers on Rachel and Berthe Lemel, which Berthe herself compiled, she stated that one French and one German man carried out the arrest, and she gave the date of December 16.

Denise had turned 9 on December 12.

The first stay in Drancy internment camp

Gitla, Berthe, Rachel and Denise were thus interned in Drancy, where they stayed for nearly three months.

Next, on February 11, 1943, Berthe and Denise’s names the appeared on the deportation list for Convoy 47, but in the end they were not deported after all (Arolsen archives).

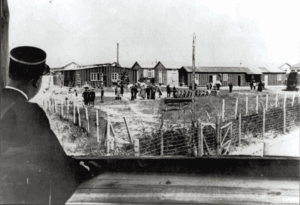

The transfer to the Beaune-La-Rolande camp…and then back to Drancy

After the first spell in Drancy, the Lemel family, along with 12 other prisoners, were transferred to Beaune-la-Rolande camp, in the Loiret department of France. They were only there for a short time, however, from March 9 – 23, 1943. This camp was guarded only by French military police and customs officers.

A French gendarme (military police officer) standing guard over the Beaune-la-Rolande camp.

Shoah Memorial, Paris.

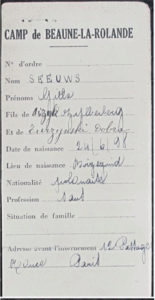

We found Gitla’s internment record, dated March 23, 1943, which states that she was a Polish national, despite her being married to a French man and no doubt having applied to be naturalized as a French citizen (which had been granted just a few weeks earlier, on February 18 1943)

Gitla Seeuws internment record from the Beaune-La-Rolande camp

French National Archives, ref. F/9/5770/308353/L

Gitla and her daughters were thus transferred back to Drancy on March 23, 1943.

On May 11, 1943, the girls were “liberated”, which actually meant that although they were released from Drancy, they were handed over to the UGIF (Union générale des israélites de France or General Union of French Jews) and “blocked” (meaning that the Germans were able to keep track of them and they were not allowed to leave). They were fist taken the UGIF center on rue Lamarck, in Montmartre, in the north of Paris. A short time later, Rachel and Denise were transferred to a children’s home on rue Granville in Saint-Mandé, out in the suburbs. Known as UGIF center 64, this was a former maternity home that belonged to a Dr. Pitowski, which opened in early June, 1943.

On December 18, 1943, a group photo of the girls in Saint-Mandé was taken in the schoolyard on rue Mongenot (Shoah Memorial collection). Denise and Rachel looked at the camera as the photographer captured a striking image (see below) of the little girls wearing the yellow star in a French school. It is featured in Jean Laloum’s, Les maisons d’enfants de I’UGIF : le centre de Saint-Mandé (UGIF children’s homes: the Saint-Mandé center) published in Le Monde Juif (Jewish world) 1995/3 (n° 155).

In the photo, Rachel Lemel is on the top left and her sister Denise is in the front row, second from the left.

Berthe, meanwhile, who was older, was transferred from the Lamarck center to another UGIF home on rue Vauquelin.

In the file she submitted on December 29, 1953, which is now held by the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy, she explained how she had managed to escape during an outing, and took refuge with a friend of her mother’s, a Mrs. Ziegler, who lived at 70 boulevard Davout, where she stayed hidden until the end of the war8. How lucky she was! All the girls in the rue Vauquelin home were later rounded up and deported on Convoy 77.

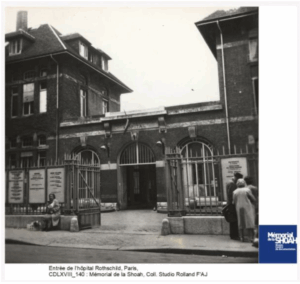

On June 5, 1943, Gitla had to have emergency surgery at the Rothschild Hospital in Paris.

The Rothschild family had founded the hospital in the 19th century to provide healthcare for disadvantaged people, in particular Jews. During the Occupation, the Germans and the Vichy regime used it as a detention center for sick and elderly Jews before they were deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

The Rothschild hospital in Paris (Shoah Memorial, Paris)

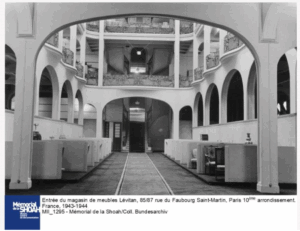

When she was discharged from hospital, Gitla was taken back to Drancy. Then, in July 1943, as she was deemed to be “non-deportable” because she was married to a non-Jewish Frenchman, the Germans transferred her and 200 other internees to the newly-opened Lévitan camp, at 85-87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin in the 10th district of Paris.

This was one of Drancy camp’s three annex camps in Paris, the others being the Austerlitz camp at 43, quai de la Gare in the 13th district and the Bassano camp, which was housed in a mansion that had once belonged to the Cahen d’Anvers family, at 2, rue de Bassano in the 16th district, just off the Champs-Élysées. During the Occupation, the Nazis used these forced-labor camps in Paris to exploit Jewish prisoners to sort and repair items they had looted from homes owned or occupied by Jewish families, and to produce luxury clothing and accessories. Their Dienststelle Westen (West Office) was responsible for this organized theft.

Gitla thus found herself in the Lager-Ost (East camp), also known as the Lévitan camp, which was named after a well-known furniture store that, prior to the Occupation, had belonged to Wolff Lévitan and his wife Berthe Bleustein. They too were Jewish and their assets, including the store, had been confiscated under the “Aryanization of the economy” policy. All Parisians were familiar with the advertising slogan coined by Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet in 1930: “A piece of furniture signed Lévitan is a piece of furniture that will stand the test of time”.

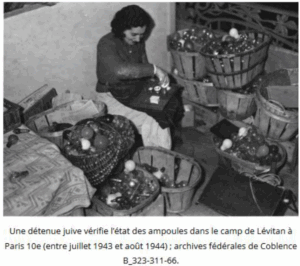

Gitla’s task was to sort property stolen from Jews after they were rounded up or deported, under the Nazis’ “Operation Furniture” program. German soldiers watched her every move. Living conditions in the Lévitan camp were generally felt to be less harsh and more bearable than those in Drancy. According to the historian Jean Laloum, who spoke at length with her daughter Bejla/Berthe in 1994, Gitla was allowed this “privilege” because she was the “spouse of an Aryan”5.

The images below illustrate the type of work that Gitla did in this forced-labor camp.

From Sarah Gensburger’s, “Spoliation des Juifs à Paris”: “Il n’y avait plus rien, même plus d’ampoule” (“Spoliation of the Jews in Paris”: “There was nothing left, not even a light bulb”)

Digital Encyclopedia of European history ISSN 2677-6588, uploaded on 27/10/23.

“This image is now held in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz. It is in an album of 85 black-and-white photographs with no accompanying text. In order to fully understand what it represents, I spent a long time gathering information, which took from 2006 to 2010.

The railings, for example, revealed that this image was taken in the Lévitan furniture store at 85-87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin in the 10th district of Paris. I have been unable to identify the woman in the photograph. I do know, however, that she was Jewish. She was arrested and taken to the Drancy transit camp on the outskirts of Paris, the departure point for most of the convoys deporting Jews from France to the extermination camps. In July 1943, she was one of 200 internees transferred from Drancy to the heart of the French capital, to a building whose rightful owner, a Jewish man named Wulf Lévitan, had been dispossessed as part of the “Aryanization” of the economy, a term used to describe the forced sale of Jewish-owned real estate, businesses and other assets to non-Jews, or “Aryans”. The property then became a forced labor camp for Jews.

In this photograph, the woman’s smile is quite striking. Many images released by the Nazi regime depict smiling Jews. In 1942, detainees in Drancy camp appeared happy in a report produced by the propaganda services to show that they were being treated well.

The image we have before us, however, does not fall into this category. The work it documents had to remain secret. The photograph was taken using a spotlight. The daylight that would normally have come in through the Levitan building’s large windows would have been more than adequate had they not been deliberately blacked out.

And with good reason: in a city where shortages had become the norm, making local residents jealous was out of the question. And the booty was truly impressive. Over the course of a year, French removal firms delivered 2,000 crates every day. The prisoners had to unpack them, sort clean the items and then put them into specific crates” explains Sarah Gensburger, a sociologist at the CNRS (French National Center for Scientific Research) who specializes in Holocaust research7.

July 21-22, 1944, the tipping point

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, SS officer Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, ordered a series of roundups of the UGIF children’s homes in and around Paris. A total of 242 children and 33 adults were arrested and taken to Drancy. Among the victims were Rachel and Denise Lemel, who were rounded up with eighteen other girls and their supervisors, including the manager, Thérèse Cahen, at the Sante-Mandé children’s home (UGIF center no. 64).

From Jean Laloum’s, “Les maisons d’enfants de I’UGIF: le centre de Saint-Mandé” (UGIF children’s homes: the Saint-Mandé center) published in Le Monde Juif (Jewish world) 1995/3 (n° 155). Rachel Lemel is on the top left and her sister Denise is in the front row, second from the left.

As soon as Gitla heard about the roundups in the UGIF homes, she asked to be transferred from the Lévitan camp back to Drancy6. According to an account recounted by Jean Laloum, a German soldier at the Levitan camp tried to persuade her that there was no point, but to no avail. In any case, Aloïs Brunner’s policy was to gather family members together and deport them all at the same time. All the mothers of the rounded-up children were transferred to Drancy and deported with them, notably on Convoys 76 and 80.

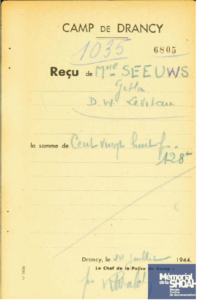

Thus, on July 24, Gitla arrived back in Drancy, where she was registered as prisoner no. 17932. According to her search receipt, she had 128 francs on her at the time.

Gitla’s search receipt from Drancy camp, dated July 24, 1944 (Shoah Memorial, Paris)

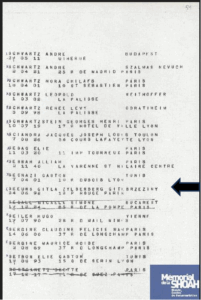

The original Convoy 77 deportation list, dated July 31, 1944 (Shoah Memorial, Paris)

On the Convoy 77 deportation list, the Germans wrote down Gitla’s address incorrectly; the original address, 12 passage des Ronces, became 12 P(lace?) rouge.

On July 31, 1944, she was put on a bus and taken to the Bobigny train station, where she and her daughters Rachel and Denise were deported by train to Auschwitz-Birkenau. There were more than 1,300 deportees, all crammed into cattle cars. The travelling conditions were appalling. According to Holocaust survivor Yvette Dreyfus Levy, “In each wagon there was one bucket of drinking water and another bucket for our needs.” The journey to Auschwitz took three days and three nights.

Did Gitla travel in the same car as her daughters? We have no way of knowing, but she may have. According to the testimonies of survivors such as Jérôme Skorka, the older children and teenagers from the UGIF homes traveled among the adults. Families were able to travel together. What happened next to Gitla and her daughters appears to confirm this.

Did they travel in the same car as Laya Rafalowicz, the girl who used to live at 9 and then 3 passage Ronce in 1931, and who was rounded up with the other girls in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin?

As of May 1944, the SS brought the trains carrying the deportees right into the Birkenau killing center.

After the deportees had been dragged roughly out of the cattle cars, they were separated, with men on one side and women on the other, and then “selected” according to the camp’s labor needs, their fitness for work and their state of health. All the seniors and children were loaded onto trucks, as was anyone holding a child’s hand, and anyone the Nazis deemed to be too old or too weak.

From the moment they stepped onto the Bahnrampe in Birkenau, Rachel and Denise, who were too young to work, had almost zero chance of survival. The SS doctors would have immediately “selected” them for the gas chambers. But that was not the case for Gitla. In fact, as Jean Laloum explains9, “on the selection ramp at Birkenau, according to Convoy 77 survivor Janine Akoun, the SS sent Gitla to the line of women fit for work”. Janine Akoun, who first stayed in the Rothschild orphanage, was then transferred to the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, where she became friendly with Berthe.

Gitla refused to be separated from Rachel and Denise. She therefore went with them as they walked unwittingly along the barbed wire fence to their deaths in the gas chambers. Courageous to the very end, Gitla steadfastly carried out her role as a mother.

We do not know exactly when they were killed. It was no doubt soon after the convoy arrived on August 3, 1944, possibly before daybreak, but their official date of death was later declared to be August 5, 1944. In the 1950s, the French authorities decided that this date would be used for all Convoy 77 deportees who had not returned to France and of whom there had been no other news.

At the age of 46, Gitla Seeuws, née Zylberberg, was almost certainly murdered on August 3, 1944 in Birkenau, in her native Poland, alongside her daughters, Rachel, who was 13 and Denise, who was 11.

After the war: Gitla’s legal status and the lives of her surviving children, Berthe and Henri

After the war, Gitla’s husband, Roger Seeuws appears to have made no attempt to have his wife’s death confirmed, and nor was he involved in the process of making his step-son, Henri Lemel, a ward of court. We found only one record that mentions his name: an “information sheet” issued by the authorities on April 25, 1946, in response to his request for information about what had happened to Gitla. It reveals that he was still living at 12 passage des Ronces in the 20th district of Paris. When he died, at the age of 50, on August 20, 1959 in the Tenon hospital, also in the 20th district, he had moved to 12, rue du Lieutenant Thomas in Bagnolet.

Gitla’s death was recorded on December 12, 1951 at the town hall of the district where she was living when she was arrested.

On September 27, 1955, Gitla was officially granted the status of “Political Deportee”. This term was introduced by a French law dated September 9, 1948, which defined political deportees as French or foreign citizens who had been deported outside France and interned or imprisoned for any reason other than breaking the law or being a member of the Resistance. It therefore covered civilian victims, victims of roundups, hostages etc. The term “Political Deportee” was therefore used for people who were deported simply because they were Jews, rather than the term “Déporté Racial” (“Race-related deportee”), which Jewish people felt more appropriate and often used in applications for the status.

In Gitla’s case, the application had been made on December 28, 1953 by the Seine department Office of Veterans and War Victims, which the Justice of the Peace of the 20th district of Paris had appointed as the legal guardian of young Henri Lemel. Berthe Lemel, who was then living at 13 rue des Deux-Ponts in the 14th district, had also approved the request.

As of November 19, 1956, the words “Mort pour la France” (Died for France) could be added to Gitla’s death certificate.

On June 20, 2001, the French authorities decreed that the words “Morte en déportation” (Died during deportation), could also be added to Gitla Seeuws née Zylberberg’s death certificate. This was a formal acknowledgement of her tragic fate as a victim of Nazi persecution.

Source : site legifrance.gouv.fr

However, even on this 2001 decree, Gitla’s death date is still given as August 5, 1944, which is incorrect.

After the war, Berthe was cared for by the OSE (Œuvre de secours enfants, or Children’s Aid Society). She stayed in the Le Tremplin home in La Mulatière, in the Rhône department of France, as evidenced by a photo taken by a journalist from the newspaper Patriote (Source: Shoah Memorial, ref. OSEII-05-35-3-). As a “Pupille de la Nation” (Ward of the State), the OSE took care of her until she legally became an adult. On November 29, 1950, the OSE applied for her to be naturalized as a French citizen. It also tried to claim an orphan’s pension for her.

Berthe went on to marry and have one son. She died on July 9, 2011, in the 14th district of Paris.

Henri, meanwhile, after his mother was arrested, was taken in by Entraide Temporaire (Mutual Aid society – a little-known clandestine network that helped and rescued Jews in Paris throughout the Occupation) and was then made a ward of court. He later recounted his story to a friend of his, Sami Dassa, which was published in Vivre, aimer avec Auschwitz au cœur (Living and loving with Auschwitz in mind), in 2002. For a long time, he lived in Jouy, in the Eure-et-Loire department of France. After a spell at the middle school in nearby Chartres, he was sent to a children’s home owned by Baron Robert de Rothschild, at the Château de Laversine in Saint-Maximin, near Chantilly in the Oise department of France. He left there with no qualifications and no job. In around 1953, Henri tried his hand at life on a kibbutz in Israel, but soon returned to France. He was granted 6700 Deutschmarks by Germany as compensation for the loss of his mother. He moved in with his sister in 1957, then married and had a son. He died on February 11, 2012, in the 20th district of Paris.

The other members of the Lemel family who lived in France, Lendla, Idessa and Frajda, were also deported and died in the camps, as did David Morawiecki, Zelman’s brother-in-law, who was married to Idessa. They were arrested in 1942, probably during the Vel d’Hiv’ roundup that took place on July 15 and 16, and transferred to the Pithiviers camp, from where they were deported. A Henri Morawiecki/Morawcaki, who was born on December 11, 1929, also appears to have been a member of the family, who lived on rue Ramponneau in the 20th district of Paris. At least one of the Lemel children’s cousins, Ms. Braun, née Butler, is still alive, and was once considered for a position on the Board of Trustees.

Esther Senot, who was raised in passage Ronce and told her story in a moving book entitled La Petite Fille du passage Ronce (The Little Girl from passage Ronce), notes that “in our passage Ronce, 27 families were affected, and 68 people were murdered” (p. 124).

Sources

1 Jan Grabowski, “Enquête sur l’antisémitisme” (Investigation into anti-Semitism), published in L’Histoire n°421, in March 2016.

2 Source: OSE files on Berthe and Henri viewed by 3e 3 and 3e 6 students at Collège de la Forêt under the supervision of Ms. Berna and Ms. Pourriot.

3 Sami Dassa, Vivre, aimer avec Auschwitz au cœur (Living and loving with Auschwitz in mind), published by Harmattan, 2002, p.162.

4 Jean Laloum, “Les maisons d’enfants de UGIF : le centre de Saint-Mandé (The UGIF children’s homes: the Saint-Mandé center), published in Le Monde Juif, 1995/3 (n° 155)

5 Jean Laloum, op. cit.

6 Jean Laloum, op. cit.

7 Sarah Gensburger, “Spoliation des Juifs à Paris”:“ Il n’y avait plus rien, même plus d’ampoule” (“Spoliation of the Jews in Paris”: “There was nothing left, not even a light bulb”), Digital Encyclopedia of European history, ISSN 2677-6588, published on October 27, 2023, viewed on April 14, 2025: https://ehne.fr/fr/node/22194. In fact, all the windows were covered with paper that blocked out the light.

8 https://en.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/denise-lemel/ File on Berthe Lemel @SHD Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-561-074

9 Jean Laloum, op. cit.

10 The original convoy list has never been found; it was recreated just after the war.

[i] The military personnel register, which contains his service record and could have provided this information, is not available online, as he was born in 1929 and records are only available up until 1921. He was enrolled in the 1st Seine office, under registration number 413.

[ii] APP CC2-3; December 16, 1942

We would like to thank the 9th grade students and their teachers at the la Forêt middle school in Traînou, in the Loiret department of France, for their research into Gitla’s daughters, Rachel and Denise, which helped us enormously.

Français

Français Polski

Polski