Herbert SAMETZ

This biography was written by the 12th grade students of class HGGSP3 (History-Geography, Geopolitics and Political science) at the Cassini high school in Clermont, in the Oise department of France, together with their teacher, Ms. Maryline Limonier, during the 2021 – 2022 school year.

Putting together the life of Herbert Sametz left us with a taste of unfinished business. Many periods of his tumultuous life remain unaccounted for, as far as we have been able to research.

Our research was based first of all on the few personal documents that Rose, Herbert Sametz’s daughter, gave us: a few letters and a photograph. We thank her immensely for the trust she placed in us, as did her children and grandchildren whom Herbert Sametz never knew. In addition, thanks to the wonders of the Internet, we were able to access various other sources (official documents, deportation certificates, etc.). We found out what had happened to him through the replies to questions that we sent to the Ministry of the Armed Forces, the Shoah Memorial in Paris, Yad Vashem, the Belgian royal archives and the Pyrénées-Orientales departmental archives service, among others.

Nevertheless, we were unable to find out about one part of his life. We would have liked to know more about his escape, his life as a resistance fighter in the Oise department and his arrest.

We knew from the beginning of our investigation (historial in Ancient Greek) that it would be difficult. We were delighted by our every find. We were doing the work of real historians. It also gave us great pleasure to be able to pass on some of our discoveries to the family, especially the portrait of Herbert Sametz’s mother, whom they never knew. Rose takes after her, apparently. By doing that, we contributed to the family history.

We will remember Herbert for years to come.

Sali-Leonia Wasser, Herbert Sametz’s mother

Herbert Sametz was born on December 27, 1922 in Vienna, Austria [1]. His father, Viktor Sametz, was the son of Josef Sametz and Rosa Kohn. He was born on November 30, 1891 in Budweis, in what is now the Czech Republic. His mother’s name was Sali-Leonia Wasser, the daughter of Ester Wasser, and she was born on November 9, 1892 in a town with a troubled history: located in the province of Eastern Galicia, it was known as Lemberg in German, Lwów in Polish and Lviv in Ukrainian. The Sametz family lived at 58 Universtrasse in the 20th district of Vienna, Austria. The address on Herbert’s birth certificate is 2 Odeongasse, Vienna, and the midwife who delivered him was Frieda Pessl Pomeranz. Thus began a life that was all too short.

Herbert grew up in Vienna as an only child, his parents having had him when they were older than average in those days. Herbert’s mother, Sali-Leonia was 30 years old and appears to have been a shorthand typist. We do not know what his father did for a living. The Sametz family lived in Vienna until 1938, when Herbert was not yet 16 years old.

A life turned upside down by events

On March 12, 1938, German troops invaded Austria in order to annex the country into “Greater Germany”. The Austrian chancellor was forced to surrender. Hitler was greeted triumphantly in Vienna. This was known as the Anschluss. As early as March 11, the Third Reich began to crack down brutally on anyone who opposed it, initiating the Nazification of Austria; anti-Semitic attacks broke out across the country. 190,000 Jews were living in Austria when anti-Semitic persecution, in particular in Vienna, increased in number, involving public shaming, dispossession and forced emigration. Even before the Wehrmacht arrived, the brutality was unleashed: there were violent scenes and bullying in the streets, and apartments and businesses belonging to Jews were looted. It is easy to understand why Herbert and his mother fled (1). Did Viktor, Herbert’s father, go with them? We do not know. It was in March 1938 that the largest exodus of Jewish refugees occurred. Finding a host country was no doubt difficult for the Sametz family. The countries of Western Europe all claimed to be overwhelmed and the French said that the country was “saturated”. They used this to justify the closure of their borders and their refusal to accept Jewish refugees. At the Evian Conference, which was held from July 6 to 15, 1938 to address the problem of Jewish refugees, Great Britain, France, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland stated one after another that they were unable to take any more refugees and would only grant transit visas.

The Sametz family managed to make their way across Germany and took refuge in Belgium, or at least Herbert and his mother did [2]. We were unable to find out any details about this dangerous journey. We know nothing of the circumstances of their escape.

Belgium: a safe haven?

Herbert and his mother arrived in Belgium in 1938. We know that this was sometime after March, but no more than that. As was the case for the majority of the refugees, they were detained in Merxplas, near Antwerp(2) since they had no passports or visas. The Belgian government made accommodation in Merxplas available to the official assistance committees in order to assemble the refugees until they were able to find asylum elsewhere. The aim was to reassure the public and to show that the assistance committees had the situation under control. The Assistance Committee for Jewish Refugees, founded in 1933, (3) provided Jewish refugees with material help (financial aid, food, lodging, clothing, coal in winter), medical assistance and legal advice to help them stay in the country legally. French, English and Spanish language courses were arranged in preparation for their re-emigration. In total, 40,000 Jewish refugees were given temporary or permanent asylum in Belgium between 1933 and 1940. A third of them, such as Herbert Sametz, came from the then annexed Austria. Herbert hoped to emigrate to Palestine, according to what he told the Belgian authorities when he registered with them [3]. He spent some time in Merxplas, but we don’t know how long he stayed there. He then moved to Brussels, perhaps together with his mother. His plan to emigrate from Europe was not easy to put into practice. It became more difficult to leave after September 1939, so they stayed in Brussels in an apartment at 72 boulevard Emile Jacquemain. But what did the family live on in Brussels? Does Herbert manage to find a job? That would be surprising given the economic downturn and the social climate. Besides, refugees were strictly forbidden to be gainfully employed. Was he living on his family’s savings? We don’t know. What we do know is that Herbert spoke and wrote French perfectly [4]. Had he learned French in school in Vienna or during his stay in Belgium? Either way, his mastery of the French language would have improved his chances of survival in occupied France.

The quality of life of the Jews in Belgium soon began to deteriorate. The Belgian government was worried about a sort of “Fifth Column” getting involved in the event of a Nazi attack. It therefore compiled a file of people of German origin: the infamous “Saint-Cyprien” list (4). The Belgian police arrested not only Belgian citizens who were German sympathizers, but also all of the Germans living in the country. Among them were about 4,000 German and Austrian Jews who had fled the Nazis and taken refuge in Belgium with their wives and children, including Herbert Sametz, who by then was nearly 18 years old.

At dawn, on May 10, 1940, the day that Nazi Germany invaded the country, on the orders of the Minister of Justice the Belgian police began a mass arrest of “enemy aliens”, “whose presence was dangerous for the security of the country”. These arrests involved only men born between 1881 and 1923. Herbert, who was born in December 1922, would have escaped had he been a year or so younger. The vast majority of the men arrested were Jewish refugees, who were deemed to be “suspicious”. As they carried out the arrests, the Belgian police ordered the refugees to take food for 48 hours. Did Herbert Sametz have the opportunity to go to his apartment to collect some food and personal belongings? This was the beginning of an odyssey for several thousand Jews, including Herbert. He had to leave on his own, without his mother.

France, a land of violence

Herbert Sametz was thus one of the 8,000 Jews expelled from Belgium to France on May 10, 1940 (5). An agreement had been reached between the two countries. The Jews were crammed into cattle or freight cars in appalling conditions and the convoys headed for the camps in southwestern France: Gurs, Saint-Cyprien, Les Milles, Vernet or Argelès. The journey lasted 15 days due to the chaos that followed the German invasion of France, as can be seen on the map of the train’s route (6). Records show that Herbert Sametz was in the Saint Cyprien camp on October 4, 1940 [5]. Among the other men there, Herbert might have met Felix Nussbaum, a German Jewish painter who, like himself, was arrested in Belgium on May 10, 1940, as a citizen of the Reich, and interned in the Saint-Cyprien camp, from which he later escaped (7).

However, the Saint Cyprien camp was soon hit by torrential rain. This was known as an “aïguat”, a Catalan term for a deluge of autumn downpours, and it was followed by severe flooding. Between 16 and 24 October 1940, the camp was devastated and had to be evacuated. During the last three days of October, Herbert Sametz was sent, along with 3,870 other men, all suffering from cold and fatigue, to the Gurs camp. These 3,870 men are referred to as the “Cyprienans of Gurs”. Their lives in the camps, and how they survived, are well-documented. A number of testimonies have been published about the harsh living conditions that the prisoners endured (8).

Herbert Sametz escaped from the Gurs camp [6]. Records show that he was there from October 29, 1940 to June 9, 1941, the day on which he escaped [7]. Only 433 escapes were recorded by the camp services, two-thirds of which occurred during 1941. Most of the escapees were young, single men (9). Herbert was one of them. He was 19 years old, had not yet met Alice and would have had no news of his parents. Prisoners rarely escapee from the Gurs camp; the challenge was not to get out of the camp, which was huge and poorly guarded, but to take advantage of their newfound freedom. Many of the escapees were recaptured. In fact, nearly half of the escapees were caught, as the police reports show.

France, a land of happiness

Herbert Sametz thus managed to leave the southwest of France. And here begins a period of almost two and a half years during which we do not know what happened to him. However, that difficult period also brought him happiness, because, “by chance” he met a girl called Alice [8]. He appears to have integrated well into his in-laws’ family. He had to travel a lot for work, which he complained about. We next found a trace of him in November 1943. From letters sent to his fiancée, Alice Leibovici, we know that Herbert made numerous trips back and forth between the capital and the Oise department, in particular the town of Saint-en-Chaussée, where he appears to have lived for a time with Alice. In 1944, another address, in Paris, is mentioned. However, these letters include no details about his work or other activities. He refers to his many “bosses”, his travels by train and by bicycle, a friend from Amiens who vanished and, more mysteriously, a soldier’s billet in Compiègne from where he wrote a letter to his fiancée and, in another letter, to the goodwill of the “Kommandantur”. Was it because he was involved in the Resistance[9] that he became so close to the occupying forces? We have no answers to this question.

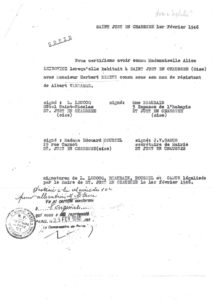

Certificate from the Mairie of Saint-Just-en-Chaussée, dated February 1, 1946

However, between the end of 1943 and the spring of 1944, his letters exude his delight at being in love and expecting a baby. His daughter was born on August 31, 1944 and was named after Herbert’s grandmother, Rose. The letters also reflect his impatience for the war to end.

The summer of 1944; Herbert’s last summer

Herbert Sametz was without doubt involved in the Resistance in the Oise department (although we have no direct evidence of this). He held fake identity documents in the name of Albert Vandamme, a known Resistance fighter, which is why he was arrested and detained in the Agel prison in Beauvais [10]. He said as much in his last letter to his fiancée, dated June 27, 1944. The Beauvais prison was a former barracks and military hospital that became an internment center for Resistance fighters between 1943 and 1944 (10). It seems, therefore, that he was not arrested because he was a Jew. After they were convicted, the Resistance fighters who were taken prisoner went from the Feldkommandantur, which was in the city center, via what is now the rue des Déportés (Deportees’ street) to the Agel barracks, which was at that time a transit facility. The French authorities handed over the political prisoners to the Germans. Herbert Sametz was thus transferred to the Fresnes prison on June 27, 1944. Then, on July 27, 1944, he was sent to Drancy (11). On July 31, 1944, he was taken by bus from Drancy to Bobigny railroad station [11]. From there, he was loaded onto a train, Convoy 77, which was made up of 1,310 deportees. 836 of them, including Herbert Sametz, were killed in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz on August 3. He was later officially certified to have died on August 5th, 1944 (12). He was not even 22 years old. He never knew his little daughter, who was born 26 days after he died.

Herbert Sametz’s death certificate

At the Shoah Memorial in Paris, Herbert’s name is inscribed on the wall of names on slab n°35, column n°12, row n°2.

What about his mother?

While we have not been able to find any records relating to Herbert’s father, and Herbert actually mentioned in one of his letters that he grew up in a single-parent family, his mother’s story is better documented. Sali-Léonia Wasser-Sametz was detained in Mechelen, Belgium. She then was deported on Convoy 20, which left the Dossin barracks for “an unknown destination” on April 19, 1943 [12]. This was in fact the twentieth convoy, which left Belgium for Auschwitz with 1,631 Jewish deportees on board, including Herbert’s mother. The history of this convoy is unusual in that Resistance fighters attempted to free the passengers. 231 of them managed to escape. This was the only such episode recorded in Western Europe during the Second World War. 153 people deported on Convoy 20 survived, but Sali-Leonia, Herbert Sametz’s mother, was not one of them. She was murdered on arrival in Auschwitz.

List of people deported on Convoy 20 (Belgium 1943)

Sources and links

Sources:

[1] Source: French Consulate in Vienna, Austria

[2] Source: Belgian Royale archives

[3] Source: Belgian Royale archives

[4] Source: Private correspondence, kindly provided by the family

[5] Source: Pyrénées-Orientales departmental archives

[6] Source: Pyrénées-Orientales departmental archives

[7] Source: Belgian Royal archives

[8] Source: Private correspondence, kindly provided by the family

[9] Sources: Saint-Just-en-Chaussée municipal archives, letter dated February 1, 1946

[10] Source: Letter sent to his fiancée, dated June 27, 1944, kindly provided by the family

[11] Source: Convoy 77 list of deportees

[12] Source: Convoy 20 list of deportees (Belgium 1943)

Links:

(1) Insa Meinen, “Je devais quitter le pays dans les dix jours, sinon on m’aurait mis dans un camp de concentration” (“I had to leave the country within ten days or they would have put me in a concentration camp”), Réfugiés juifs d’Allemagne nazie en Belgique 1938-1944, Les Cahiers de la Mémoire Contemporaine [on line], 10 | 2011, posted on December 1, 2019, viewed on August 10, 2022. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cmc/488; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/cmc.488

(2) https://www.arch.be/index.php?l=fr&m=actualites&r=toutes-les-actualites&a=2014-12-08-le-centre-penitencier-de-merksplas-durant-la-seconde-guerre-mondiale

(3) http://marolles-jewishmemories.net/fr/le-comite-dassistance-aux-refugies-juifs/

(4) Jacques Déom, “La liste de Saint-Cyprien” (The Saint-Cyprien list), Les Cahiers de la Mémoire Contemporaine [Online], 8 | 2008, posted on February 1, 2020, viewed on August 10, 2022. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cmc/757; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/cmc.757

(5) https://www.ushmm.org/media/dc/HSV/source_media/all_cataloging/general/pdf/source_33334_prepablog.pdf

(6) http://histoires-du-roussillon.eklablog.com/les-internes-juifs-de-belgique-a-saint-cyprien-1940-a108164572

(7) https://www.museumsquartier-osnabrueck.de/ausstellung/sammlung-felix-nussbaum/

(8) http://www.campgurs.com/le-camp/lhistoire-du-camp/p%C3%A9riode-vichy-40-44-les-diff%C3%A9rents-groupes-dintern%C3%A9s/l-internement-des-3-870-cypriennais-les-293031-oct-40/

(9) https://www.cairn.info/revue-guerres-mondiales-et-conflits-contemporains-2021-4-page-9.htm

(10) http://oise.pcf.fr/27718

(11) https://drancy.memorialdelashoah.org/le-memorial-de-drancy/qui-sommes-nous/histoire-de-la-cite-de-la-muette.html

(12) https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000030046134

Français

Français Polski

Polski