Jacob SMOLAR (1893-1944)

Jacob Smolar, who was Jewish, was born on July 8, 1893 in Alexandrowski, Russia. His parents, who were also Russian, were Khouna Smolar and Khaye Polonski. We know nothing about Jacob’s childhood, but we do know that on March 4, 1920, in Paris, he married Esther Felda, who was also both Russian and Jewish. She was born in Vielun, in Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire. Jacob’s father, Khouna Smolar, attended the wedding but his mother was no longer alive. Jacob therefore appears to have emigrated to France at least with his father, and possibly with some other family members too. Did they move to France in order to flee the widespread anti-Semitic pogroms that had begun sweeping across Eastern Europe and Russia at the turn of the 20th century? Were they perhaps fine folk or wealthy landowners who fled the Russian Empire after the Bolshevik revolution in 1917? There is nothing in the archives to suggest this, but such events may well have been what drove them into exile. We do not know if Jacob met his future wife, Esther, after he arrived in Paris or back home in Russia, but that seems less likely as the towns in which they were born were quite far apart.

Jacob and Esther set up home in Paris and, in 1921, had a daughter, Ginette. The family lived at 28 rue des Boulets in the 11th district, in a Haussmann-style building not far from Place de la Nation. Jacob was a tailor by trade. By 1920, when he got married, he had already become a French citizen. They were thus a French family from an immigrant background, and the fact that they named their daughter Ginette, a French name, suggests that they were keen to assimilate into Parisian society. Like many migrants of their generation, they would have spoken French during the day and probably Russian at home. They may sometimes have spoken Yiddish as well, which was the language spoken by Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

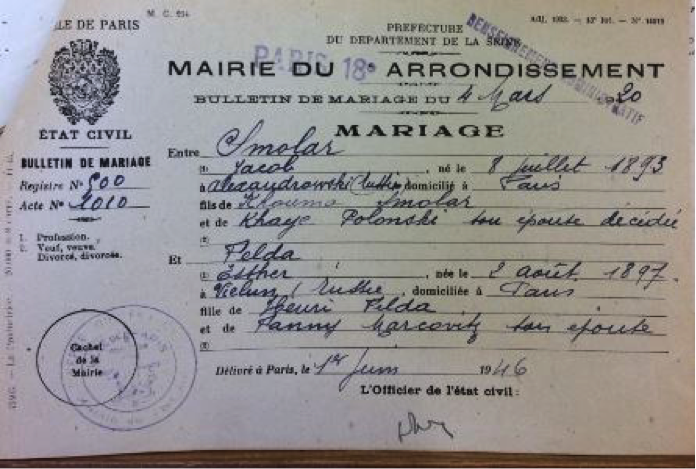

Jacob Smolar and Esther Felda‘s marriage certificate, dated March 4,1920. . It was sent to Ginette Smolar on June 1, 1946, when she was putting together a missing persons’ application.

Source: Smolar Jacob, French Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier n°21P539707

Jacob lived through the outbreak of war in 1939 and, after France was defeated in 1940, the German Occupation. He watched on as Marshal Pétain came to power and made France an authoritarian, anti-Semitic state. In 1940, the Vichy regime passed a series of decrees known as the Status of the Jews, which discriminated against Jewish people and barred them from working in certain professions, such as doctors, lawyers, factory managers and school principals. While Jacob, as a tailor, was not affected by the employment legislation, he was soon affected by several other policies, such as the census of the Jewish population and its assets, in 1941, and the requirement to wear the yellow star introduced in 1942. He also lived through the horror of the Vel d’Hiv roundup, during which over 4,000 French police officers scoured the streets of Paris and the surrounding area arresting Jews – over 13,000 in all, including 4,000 children, and took them to the Velodrome d’Hiver (Winter Cycling track). What did Jacob do during this time? Did he go to register himself as a Jew? Did he wear the yellow star? Conversely, did he and his family go into hiding for fear of being arrested and deported? Was he aware that the Jews in Paris were arrested as part of Hitler’s “Final Solution” in 1942? What did he think? How did he feel? He must inevitably have been afraid for himself as well as for his wife and daughter Ginette. In response to all these questions, our best guess is that Jacob and his family went into hiding to avoid the Nazi threat. This is borne out by the fact that the records state that Jacob and his wife were arrested by the French militia following a tip-off. They were captured in their apartment, so we can only surmise that they had not registered themselves as Jews but nevertheless continued to live at home.

Jacob and his wife were arrested on July 18, 1944, just over a month after the Allies had landed in Normandy on June 6. We can imagine his optimism as the Allies steadily advanced towards Paris. The Germans, however, hell-bent on continuing their murderous rampage, stepped up their hunt for Jews in 1944, which served as further proof of their intent to commit genocide. Jacob and Esther were among the last people deported from France to the death camps in the summer of 1944. On July 19, they were taken to Drancy internment camp, north of Paris, the main departure point for trains bound for Germany and Poland. On July 31, they were loaded onto Convoy 77 and deported to Auschwitz. The French Ministry of Veterans Affairs estimated that the journey took five days, although we now know that the convoy arrived in Auschwitz on August 3. We can only imagine how they must have felt that day: exhausted, after the long journey locked in a cattle car, with hardly any food or water, no toilets, crammed in with dozens of other deportees, all utterly dehumanized. Then came the selection, during which the Nazis sorted people into lines: the younger, fitter people who would be sent into the camp for forced labor and the those who would be sent to the gas chambers and murdered immediately. Children under the age of 14 and anyone over the age of 50 were always selected for execution. Jacob was 51 years old at the time, and Esther 47. Were they separated for the final time, there on the ramp? Or were they executed together, as soon as they arrived? Either way, they never came back from Auschwitz, where they were murdered by the Nazis.

In 1946, over a year after France was liberated, Esther and Jacob’s daughter Ginette applied to the public prosecutor of the Seine department for a court ruling confirming that her parents were still missing. For some reason, she was not arrested at the same time as her parents. She was 21 years old at the time, so she may have been living elsewhere by then, or perhaps she was simply not at home that day. In common with so many other people in the immediate aftermath of the War, she must have worried about what had become of her parents: had they simply been deported? Perhaps they would be repatriated, but that would take time, as the war had wrought so much destruction. Along with the rest of the population, she must have seen the photos of the concentration camps, and followed the news reports about the Nuremberg trials (1945-1946), yes still she did not know what had become of her parents.

Ultimately, in accordance with a French decree issued in 1946, which stated that if there was no news of a deported person five years after they went missing, they were to be declared dead, Esther and Jacob were pronounced dead in 1950. Their official date of death was August 5, 1944.

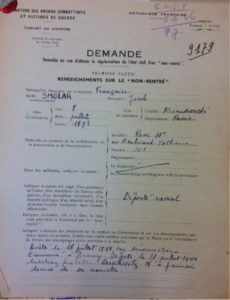

A page from Ginette Smolar’s 1946 application for an official change of Jacob’s civil status. Five years later, when a missing person’s certificate was issued, she was able to obtain a formal death certificate. It says that Jacob had been arrested following a tip-off. It also shows that Ginette Smolar was still not certain that her parents had been deported to Auschwitz.

Source: Smolar Jacob, French Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier n°21P539707

This then, is how Jacob Smolar’s story fits into the history of the Occupation and the Holocaust. In all, some 135,000 people were deported from France to camps and killing centers in Germany and Poland. Of these, around 60,000 were deported as a result of repression (resistance fighters, political opponents, communists, etc.) and around 75,000 simply because they were Jews. Of these Jews, only 3.5% survived, and nearly 60%, including Jacob and Esther, were murdered as soon as they arrived in the camps

This biography is based on records from the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy: Smolar Jacob, dossier n°21P539707.

Français

Français Polski

Polski