JACQUES STEINBERG

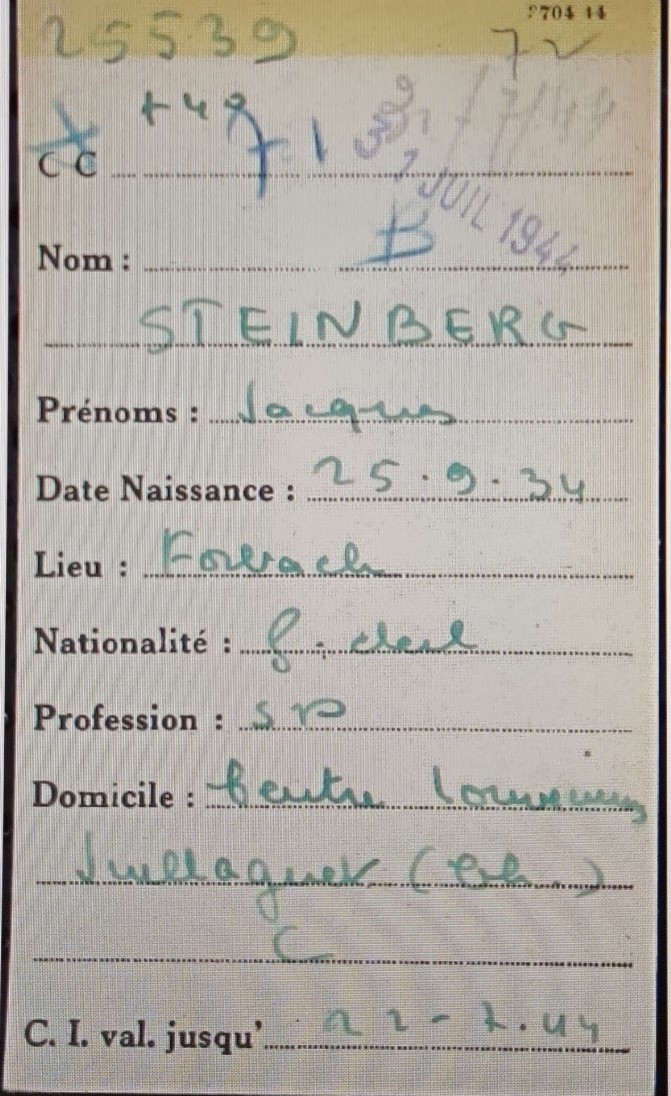

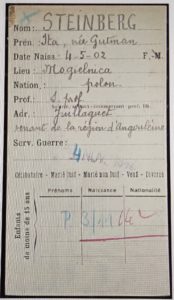

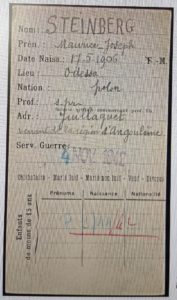

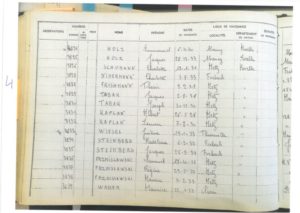

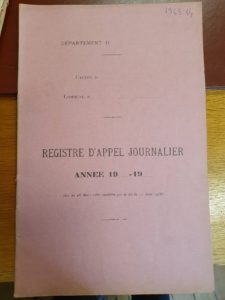

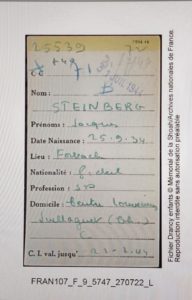

Since there are no photographs of Jacques, we have decided to show his internment card from Drancy camp. As we will explain later, it provides a summary of his life (source: the Shoah Memorial in Paris).

We are 28 11th grade students from class techno 2, ST2S (Health and Social Sciences and Technologies) at the Georges de La Tour high school in Metz, France. The class is made up of 26 girls and 2 boys.

1. TWO NAMES ON THE MEMORIAL PLAQUES

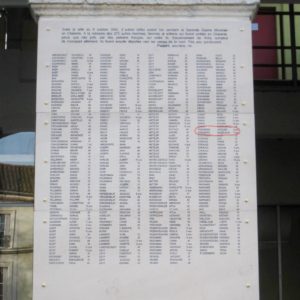

When we began researching Madeleine and Jacques Steinberg in October 2021, only two plaques mentioned their names, one in Louveciennes and the other in Angoulême. They appeared to have been forgotten in their hometown since, unlike their parents, they are not listed on the plaque in the old synagogue in Forbach. Only Richard Niderman, who is distantly related to these children, knew of their existence and had some information about them. We are pleased to have rescued them from the oblivion into which they had fallen since 1944.

The memorial plaque in the old synagogue in Forbach. The names of Jacques and Madeleine’s parents appear on it, but not theirs (photo kindly provided by Richard Niderman).

The second commemorative plaque in the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême, in memory of the 273 Jewish deportees arrested in the Charente region other than during the roundup on October 8, 1942 (from the website www.fondationshoah.org).

The plaque commemorating the people who were arrested on July 22, 1944, on rue de la Paix in Louveciennes (photo kindly supplied by Richard Niderman).

2. OUR RESEARCH

HOW WE CARRIED OUT THE WORK

Our work was organized in the following manner. We began by visiting the Convoy 77 website to read the biographies of some of the other children from Metz, (Charlotte Schuhmann, Charlotte Brzezinski, Bernard Berkowicz), in order to learn about the important milestones in their lives. We noted a number of similarities in the backgrounds of these children and this enabled us to draw up a chronology.

Every two weeks, as part of our Moral and Civic Education classes, our teachers gave us a set of documents about each of the main phases in the Steinberg children’s lives. During the subsequent lesson, working in groups, we had to analyze these documents and prepare a written summary. On each occasion, one or two groups gave an oral presentation of what they had done, and we discussed their work, added to it, and thought about any corrections or clarifications that might be necessary. The idea of creating a family tree seemed important to us. Little by little, the lives of these children took shape, even though there were still many unanswered questions.

WHAT WE GAINED FROM THE PROJECT

We had the opportunity to conduct a real historical investigation, which we had never done before. It’s pretty amazing to see how much information can be obtained from analyzing records in great detail and putting it into context.

By focusing on these children, we have increased our knowledge of the Second World War in general and of the Holocaust in particular. Above all, this project offers a more “human” approach to history. We became quite attached to Madeleine and Jacques, especially since they come from Forbach, a town that some of us know very well. By reconstructing their life stories, we were able to understand a little better what the Holocaust really involved.

The work in groups (in alphabetical order, as stipulated by our teachers) was very effective. It taught us to organize ourselves and to overcome some initial difficulties and reticence, especially through the use of digital technology.

Finally, the regular oral presentations meant that we had to make an effort to be clear and helped us to prepare for the oral exam at the end of our final year.

WHAT WE WOULD LIKE TO HAVE FOUND

We would have liked to have found some pictures of the children. It is very sad to think that there is not a single photo of them, when they could still be alive today.

We would also have liked to have found some personal details or testimonies about them rather than just official documents. This would have enabled us to get to know them better. Instead, we were reduced to making assumptions and deductions based on the lives of the other children, about whom a little more is known.

SUMMARY

This was a project that we were not expecting at the start of the year, but which all of us found interesting. It was a different way of working and learning. There were some disagreements among us: some of us would have liked to continue working on it (although a historical investigation never ends!), while others felt that it was a bit too time-consuming (but a historical investigation inevitably takes time!).

3. THE RESULTS OF OUR INVESTIGATION

A BOY FROM FORBACH

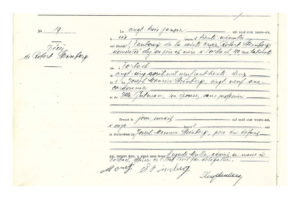

Jacques was born on September 25, 1934 in Forbach, in the Moselle department of France. His parents were Itta Gutman and Joseph Steinberg. The couple had three children in total. The first, Robert, was born on April 25, 1932 in Forbach. His birth certificate states that he was declared a French citizen according to the Nationality Act of 1927. Sadly, Robert died on January 23, 1936 in Forbach, but the cause of his death is unknown. Jacques never really knew him, as it were. As for Madeleine, who was born on February 6, 1937 in Forbach, her story is very closely linked with that of Jacques.

Robert Steinberg’s birth certificate (Forbach Municipal Archives)

We asked the French National Archives service for the three Steinberg children’s applications for French citizenship by naturalization. These files could not be found, unfortunately, not even Robert’s. However, there is every reason to believe that Madeleine and Jacques were also French citizens, as mentioned in other records that we shall discuss later. Their parents, on the other hand, remained Polish citizens.

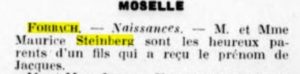

Laurence Klejman of Convoy 77 found, on the RetroNews website, a birth announcement for Jacques in L’Univers Israélite (“The Jewish Universe”) dated November 2, 1934. The fact that it appeared in a Jewish magazine suggests that the family was quite religious.

Jacques Steinberg’s birth certificate (Forbach Municipal Archives)

Birth announcement of Jacques Steinberg, which was published in L’Univers Israélite on November 2, 1934. (Source: RetroNews website)

Robert Steinberg’s death certificate (Forbach Municipal Archives)

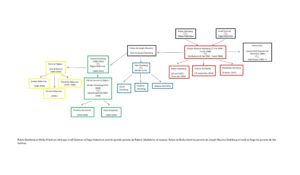

LA FAMILLE DE JACQUES

The Steinberg-Gutman-Niderman- Brzezinski family tree

Jacques’ mother, Itta Gutman (also known as Ita or Ida), was born on May 4, 1902 in Mogielnica, Poland. His father, Joseph Maurice Steinberg, was, according to most sources, born on May 17, 1906 in Odessa, Russia, but it is more likely that he was born in Chelm, Poland, as stated on his son Robert’s birth certificate. Joseph Maurice, generally called Maurice, worked as a shoemaker. All available records say that the family lived at 180, rue Nationale in Forbach.

* The maternal side of the family

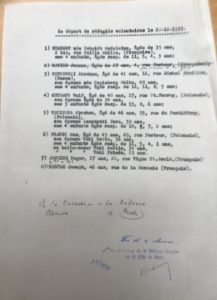

According to the address records provided by the Metz Municipal Archives, Itta left Poland in 1926 to move to Metz with her mother, perhaps after the death of her father. They both stayed initially with Itta’s brother, Wulf, who worked as a carpenter and lived at 17, rue Saint Ferroy. It was only by chance that we discovered that Wulf even existed. We found him on a record dating from December 1939, when he fled Metz with his wife and three children to go to the Charente Inférieure department. The research databases on the Shoah Memorial website and on Serge Klarsfeld’s Memorial of the Jewish Deportees of France state that his entire family was deported on Convoy 66 and that they did not survive.

Official report on the 6th convoy of voluntary evacuees to the Charente Inférieure on December 22, 1939, compiled by a local charity, the Bureau de Bienfaisance de Metz, the Metz Benevolent Agency (Metz Municipal Archives)

On her residence record, Itta is listed as a servant. She seems to have moved house frequently. She apparently spent the whole of 1927 in Toul. She left Metz in 1930, first for Merlebach and then for Forbach, where she had her first son with Joseph Maurice Steinberg in 1932 and then married him in 1934. In 1932, her mother, Fajga Gutman, came join her in Forbach. As the town no longer has any address records, we cannot know whether she lived with her daughter or whether she had a place of her own.

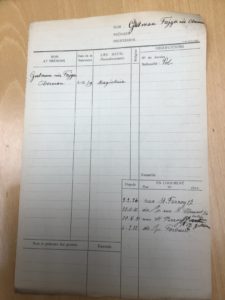

Residence sheets for Itta Gutman and Fajga Gutman (Metz Municipal Archives)

Joseph Maurice Steinberg and Itta Guttmann’s marriage certificate (Forbach Municipal Archives)

* The paternal side of the family

Maurice Steinberg had two brothers, Samuel and Max. They were also shoemakers and lived in Forbach. Both were witnesses at Maurice and Itta’s wedding. According to Richard Niderman, his nephew by marriage, Samuel was the first to arrive in France in 1920 and he brought over brothers to join him. He was married to Régina Niderman and had a daughter, Martha or Bella, who married Jacques Brzezinski and was the mother of Charlotte Brzezinski. Both of them were deported on Convoy 77 (see their online biographies). Max, the only one of the three brothers to survive the war, married Berthe Laufer with whom he had three children: Génie, Paulette and Jacques.

Richard Niderman kindly provided us with a photo of the Steinberg-Niderman family that probably dates from 1931, the year in which his father, Léon Niderman, Regina Steinberg’s brother, arrived in France. This photo is particularly important to us because it is the only photograph that shows Madeleine and Jacques’ parents. The extended family was apparently very close and got together regularly. Madeleine and Jacques were therefore very close to their second cousin Charlotte Brzezinski and her second cousins, Joseph and Charlotte Niderman, Léon’s first two children.

Photo of the Steinberg-Niderman family, probably taken in 1931 (photo sent to Richard Niderman by Paulette Steinberg)

THE FAMILY’S DEPARTURE FROM FORBACH IN SEPTEMBER 1939

We know that the border areas of Germany were evacuated as soon as war was declared in September 1939. As a result, Samuel and Regina Steinberg left Forbach. They travelled by train from the Saint-Avold railroad station to western France. We do not know the date on which Maurice and Itta left, but a census record shows that they took refuge in Juillaguet in the Charente department. However, we do not know when they arrived there. From other records that we will discuss later on, we know that Itta’s mother went with them.

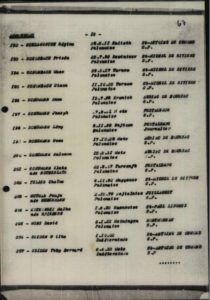

Census of refugees in Charente, probably dating from 1942, which shows that Maurice and Itta Steinberg were staying in Juillaguet (Charente Departmental Archives)

Thanks to the mayor of Juillaguet, we were able to contact Mrs. Bernadette Dussidour, whose grandfather was the mayor of the village during the war. When she was a child, her grandmother told her about the refugee families from Forbach. Her grandmother took in a number of refugees herself, in fact, and she kept in touch with them afterwards. According to Mrs. Dussidour, the Steinbergs stayed with the Vignaud family in a hamlet called Les Planets. The Vignauds’ descendants do not have any written evidence of this, however.

THE PHILHARMONIC HALL ROUNDUP IN ANGOULEME (OCTOBER 8, 1942)

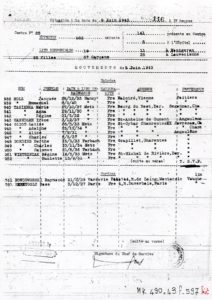

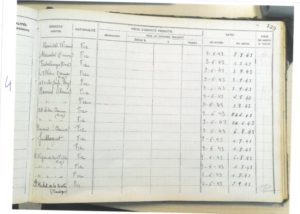

Along with all the other foreign Jews living in Charente, Maurice and Itta Steinberg were arrested during a roundup on October 8, 1942. They were among over 400 Jews taken to the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême. Their names are listed on the commemorative plaque that was unveiled there in 2012. They were also among the 387 Jews who were then transferred to Drancy on October 15. We managed to find the Drancy internment records for Itta and Maurice. Like most of the people rounded up in Angoulême, they were deported on Convoy 40, which left Drancy for Auschwitz on November 4, 1942, and were sent to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived at the camp.

The plaque in memory of the Jews deported from Angoulême after the Philharmonic Hall round-up, which was unveiled in 2012. The names of Itta and Maurice Steinberg are inscribed on it (photograph taken by Richard Niderman).

Itta and Maurice Steinberg’s internment cards from Drancy camp (Shoah Memorial)

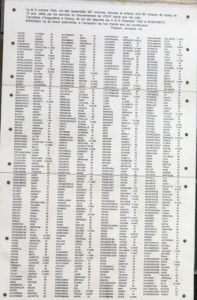

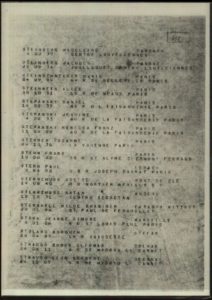

If we look carefully at the plaque in Angoulême, we see that it bears the name of Fovja Gutman, aged 63. This could be Fajga, Ida’s mother. We had found no trace of her after she left Metz in the early 1930s. We then checked the Shoah Memorial research database, where we found an entry for Fajga, in which her date and place of birth match those of Jacques and Madeleine’s grandmother. She was among the people deported on Convoy 40. Her name is on the convoy list and it says that she came from Juillaguet. We can therefore conclude that she was a refugee there, together with her children and grandchildren. One curious detail struck us, however: although such lists were usually compiled in alphabetical order, “Fouja Gutman” is listed on the same page as the Charlotte Schuhmann’s parents and brother.

Extract from the list of people deported on Convoy 40, on November 4, 1942 (Arolsen Archives)

MADELEINE AND JACQUES – WERE THEY HIDDEN CHILDREN? (OCTOBER 1942 – JUNE 1944)

As for Madeleine and Jacques, we were unable to find any records relating to them until June 9, 1943. According to Mrs. Dussidour, the two children were kept hidden in the back of a house (in Les Planets, perhaps?) until they were reported and then arrested. This oral testimony, which is circumstantial and somewhat vague, was however confirmed by the Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation (Resistance and Deportation Museum) in Angoulême, which reports that the children were arrested after their parents. We have no idea why, unlike most of the other families (the Schuhmanns, the Brzezinskis, the Berkowiczes and the Franks), the children were not rounded up on October 8. Were they kept out of sight when the gendarmes came? We do not know when they were finally arrested either.

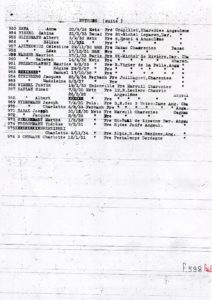

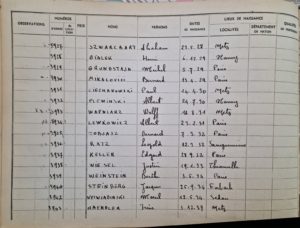

The next trace we find of them is on June 9, 1943, when they were admitted to the Lamarck center in Paris. This was a children’s home run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews), an organization that took in Jewish children separated from their families when their parents were deported. There, Madeleine and Jacques met up with their “cousins” from Forbach, Charlotte Brzezinski, Charlotte and Joseph Niderman, as well as Charlotte Schuhmann who was friends with Charlotte Niderman. There were also a number other children from Metz and the Moselle department.

According to Joseph Niderman’s testimony, they had spent the previous three days in a barn near the covered market in Angoulême. The report mentions that they came from the Charente rather than from Angoulême, as the other children had done. We also note that Jacques and Madeleine were French citizens and that their last known address was in Juillaguet. The two children were registered one after the other: Jacques was number 964 and Madeleine 965.

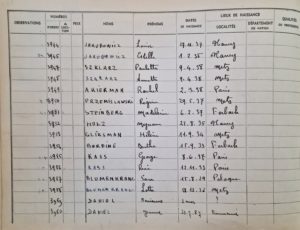

Register of admissions and departures from the Lamarck center of June 9, 1943 (Shoah Memorial)

MADELEINE AND JACQUES IN THE LAMARCK CHILDREN’S HOME (JUNE – OCTOBER 1943)

Thanks to the Centre Israélite de Montmartre (Montmartre Jewish Center), which occupies the former Lamarck Center, we have a page from the register of admissions and departures of children. On it, we found the record of arrivals from Angoulême. We also found out that Jacques and Madeleine left the home on July 1, 1943. The register does not say where they went, but we can assume that since it was school vacation time, they would have been sent, along with other children, to a UGIF center in the countryside. We do not know which center they went to and there is nothing to say that they went to the same one. Madeleine returned to Lamarck on September 3, whereas her brother had got back the day before. According the register, however, both of them, along with several other children, left the center together for good on October 12 and were sent to another home in Louveciennes. It was by then a year since they had been so abruptly separated from their parents.

The Lamarck Center register for June 9, 1943 (Montmartre Jewish Center)

The Lamarck Center register for September 2, 1943 (Montmartre Jewish Center)

The Lamarck Center register for September 3, 1943 (Montmartre Jewish Center)

Lamarck Center record of admissions and departures on October 12, 1943 (Shoah Memorial)

JACQUES AND MADELEINE IN LOUVECIENNES (OCTOBER 1943 – JULY 1944)

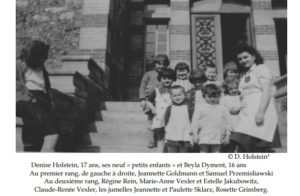

In Louveciennes, Jacques and Madeleine stayed at Séjour de Voisins (Neighborly Home), a former agricultural orphanage that the UGIF had converted into a reception center for children separated from their parents. It also offered short stays for children from other centers during the summer (Charlotte Schuhmann, Joseph and Charlotte Niderman, who were staying in the Lamarck home, spent the month of September there). They joined a group of about 40 children with whom they stayed for the entire 1943-1944 school year. For these last few months of their existence, all we have are administrative records, but the testimony of Denise Holstein, a supervisor at the center, helps us to gain a better understanding of what life was like for them. Originally from Rouen, Denise arrived in Louveciennes on July 27, 1943 when she was only 16 years old. As one of the oldest children in the center, she looked after the younger ones and became a supervisor. She was in charge of a group of 9 children. To ensure that their story would never be forgotten, she wrote a book entitled Je ne vous oublierai jamais, mes enfants d’Auschwitz (I will never forget you, my children of Auschwitz) which was published in 1995 by Editions 1. She keeps in regular contact with Richard Niderman and was kind enough to answer our questions.

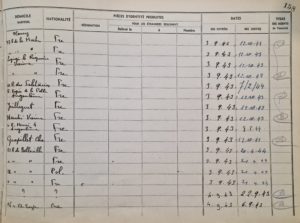

We were also lucky enough, thanks to Ms. Claire Podetti, one of the coordinators from the Convoy 77 association, and Ms. Corinne Rachel Kalifa of COMEJD, the Conseil National pour la Mémoire des Enfants Juifs Déportés (National Council for the Remembrance of Deported Jewish Children), to be introduced to two teachers, Ms. Catherine Tanguy and Ms. Muriel Baudry, who, with theirs students, have been working on the lives of some other children from Louveciennes, Jean-Claude Karpinski and Simone Goldberg. We were thus able to take advantage of the results of their research. Ms. Baudry had contacted the Leconte de Lisle elementary school in Louveciennes where the children from the UGIF center went to school. The principal of the school, Ms. Christine Heuzard La Couture, had retrieved the roll call registers for the school year 1943-1944, in which the children’s attendance was noted each day.

Cover of the boys’ roll call register from the Louveciennes elementary school for the school year 1943-1944 and a page from March 1944 (Leconte de Lisle School in Louveciennes)

These registers were kept as of Monday, October 18, 1943. The children had arrived at the center on Tuesday, October 12, so they had only had a few days to get used to their new environment. Jacques was an industrious student, missing a total of only five half-days in March 1944 due to a foot problem. Madeleine, on the other hand, was often absent. Having probably been shaken by the all the upheaval, she may have been quite a frail child. It is easy to imagine that Jacques, as her big brother, was very protective of her.

Ms. Tanguy got in touch with Mr. Bernard Guerlesquin, who went to school with Jacques. He has no memories of Jacques in particular, but he remembers the group of Jewish children who had to wear the yellow star and that he played with them at break times. Unlike the other children, who also played together on Sundays, the Jewish children stayed at the center and were obviously not allowed out. In her testimony, Denise Holstein does, nevertheless, mention outings to the park in Marly. She remembers above all the very tough living conditions at the center. She and the other supervisors gave the youngest children all the affection they could muster and tried to brighten up their day-to-day lives.

When Richard Niderman asked her about the Steinberg children, she only remembers that they had brown hair. This may sound like a minor detail, but it is very important to us because it is the only non-official information that we have about them. She also says that one day Jacques unintentionally pushed her. Mr. Louy, the manager who was well-known to be very strict, wanted her to hit the child, but she did not do it.

On January 1, 1944, because the Germans commandeered the Séjour de Voisins building, the children had to move again, this time to a villa on rue de la Paix. The villa was big but not at all suitable for 40 children, who were crammed into the bedrooms up to nine at a time. This was yet another upheaval for them.

The villa on rue de la Paix

THE ARRESTS (JULY 22, 1944)

Alois Brunner, the commander of Drancy camp, came to this villa on July 22 at around 6 a.m. to arrest the children. Denise Holstein recalls that he rang the doorbell, and there was already a bus waiting outside. Having been interned previously in Drancy, from which she was released on medical grounds, she knew what was in store for the children. However, she had to wake them up, reassure them, help them to get dressed and quickly gather together a few belongings despite the Germans, who wanted to get the operation over with before the curfew ended, becoming increasingly angry. Mr. Gherlesquin confirmed that the children were quite calm, and explained that there were not many people there, probably because they were kept out of the way. 41 children were arrested. Paulette Szklarz, a six-year-old, was the only one lucky enough not to be arrested, as she was in hospital at the time. On the bus, the children, who had been told that they were going on an excursion, were singing. Then they arrived in Drancy, where they met up with the children from the other UGIF centers who had all been arrested that same day.

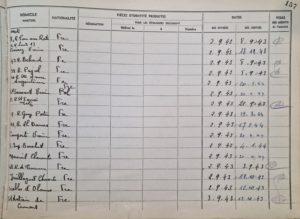

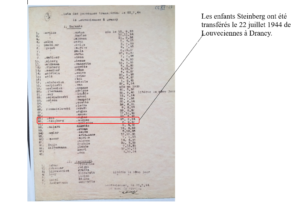

List of people arrested in Louveciennes and transferred to Drancy on July 22,1944 (Shoah Memorial)

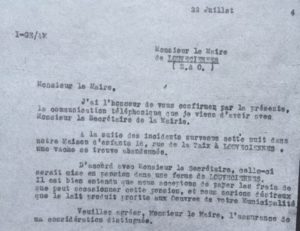

The Shoah Memorial archives include an unsigned letter dated July 22, 1944. Addressed to the mayor of Louveciennes, it refers to a cow that was abandoned “following the incidents that occurred last night in our children’s home”. Was the cow providing fresh milk for the children and helping to keep them occupied? Denise Holstein has no memory of this. She even explained that the garden of the villa was very small, that tables were sometimes set up for the children to eat outside and that she does not see how a cow could have walked among the tables.

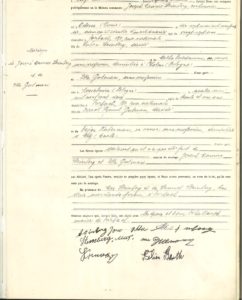

Unsigned letter addressed to the mayor of Louveciennes on July 22, 1944 (Shoah Memorial)

INTERNEMENT IN DRANCY (FROM JULY 22 – 31, 1944)

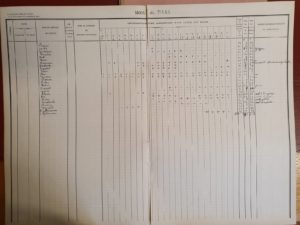

The Drancy transfer logbook shows that Madeleine, Jacques and several other children from Louveciennes were assigned to Staircase 7, Room 2. They probably met up with their cousins Jakob and Charlotte Brzezinski and the Niderman children. However, the two Niderman children left Drancy on July 24, when they were deported to Bergen Belsen on Convoy 80.

Drancy transfer log for July 22 1944 (Shoah Memorial)

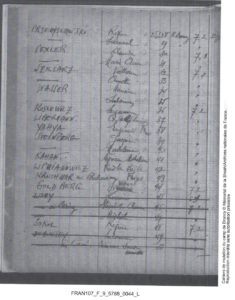

Jacques’ internment record is numbered 25539, and thus comes before Madeleine’s, which is numbered 25540. In just a few words, abbreviations and dates, it recounts his short life, from his birth in Forbach to his stay in Louveciennes, by way of Juillaguet. The note “+ fam” meant that he was not the only person in his family to be interned. The note “F. décl”, meaning “French without proof” confirmed his nationality. As for the letter “B” written in blue, this meant that he was subject to immediate deportation. The stamp in blue ink means that he left Drancy on July 31, 1944.

Jacques internment record from Drancy (Shoah Memorial).

According to Denise Holstein’s testimony, when they arrived at Drancy, the children were afraid, distraught and in need of reassurance. On July 29, 1944, Denise heard that the children might be deported, but she was still hopeful that the Allies, who had landed in Normandy on June 6, would arrive in time to save them.

Sadly, however, on July 31, 1944, the Allies had not yet reached Paris, so Convoy 77 set off with more than 1300 people aboard, including Jacques and Madeleine Steinberg.

The children were taken in buses to the Bobigny train station, where they were shut into cattle cars with about 60 other people. There were limited provisions, a few mattresses and a couple of buckets, which soon filled up and overflowed, causing an unbearable stench. Conditions on the journey were appalling. Denise describes it as an “ordeal”. She and the other supervisors had to take care of the petrified children, try to stop them crying and comfort them in the darkness, despite the thirst and the stifling heat.

List of people deported on Convoy 77 (Arolsen Archives)

Convoy 77 arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944. On August 5, the children were sent to the gas chambers. Of the 33 people from Louveciennes who were deported, only Denise Holstein, who was 17 years old, was selected to go into the concentration camp and managed to survive.

4. THEIR MEMORY WILL LIVE ON, NO MATTER WHAT

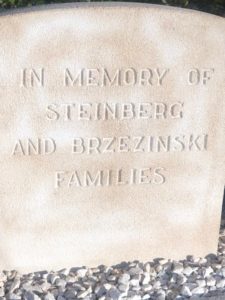

Jacques and Madeleine Steinberg must never be forgotten, and our work will help to keep their legacy alive. Some people in Juillaguet still remember them too, even though the memories are no longer very clear. Denise Holstein’s recollection of Jacques is also very important to us. We also found out, during our investigation, that a memorial ceremony takes place each year near the commemorative plaque in Louveciennes. Finally, last fall, memorials to several Jewish families were erected in Siedliszcze in Poland on the site of the Jewish cemetery that was destroyed during the war. Siedliszcze, which is near Chelm, was the home village of the Nidermans, Steinbergs and Brzezinskis. Richard Niderman took part in the inauguration ceremony.

Memorial stone on the site of the former Jewish cemetery in Siedliszcze (photo by Richard Niderman)

Français

Français Polski

Polski