Justin WIESEL

Photograph of Justin Wiesel at the Lamarck UGIF center, taken in 1943 or 1944

(Serge Klarsfeld collection, Shoah Memorial, Paris)

We are the 12th grade students of class 7 at the Louis Vincent high school in Metz, in the Moselle department of France, and this year we travelled back in time to retrace the story of Justin Wiesel, a young victim of the Holocaust from Thionville who was deported on Convoy 77. We began our investigation by studying a dossier compiled after the war, at his uncle’s request, to confirm that he had been deported to the death camps, and also a photograph of Justin taken at the Lamarck center in Paris in 1943 or 1944. From these two sources, we have reconstructed his life story, from when he was born in Thionville in 1933 to his death in Auschwitz in 1944.

I. Justin, a “non-returnee”

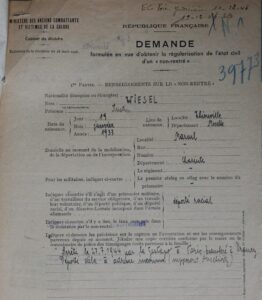

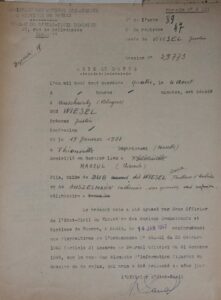

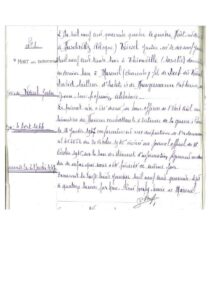

We were able to trace Justin Wiesel’s life story from a file at the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, in Normandy, since his uncle Eizik Wiesel had applied to the Ministry of Veterans and War Victims to have his nephew’s death officially acknowledged. The application was submitted in Metz on October 3, 1946. Until then, he had been classified as “non-returnee”. This term was used in those days to describe the fate of people who were deported during the war and of whom there was still no news after the camps had been liberated. It was therefore unclear if such people were still alive, given that there were no official records of their deaths.

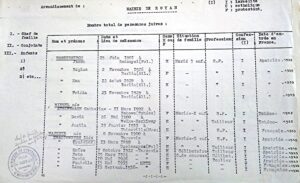

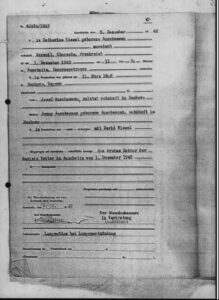

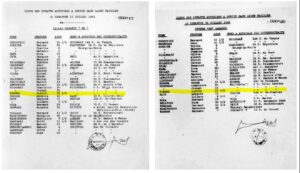

Excerpts from Eizik Wiesel’s 1946 application to have Justin Wiesel’s civil status amended, and research form (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.)

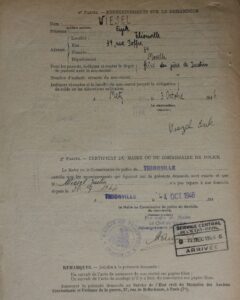

The file on Justin Wiesel, bearing the number 39.773, states that the Gestapo rounded him up in Paris on July 27, 1944, transferred him to Drancy and then, almost certainly, sent him to Auschwitz. In January 1947, the investigation concluded that Justin had “died during deportation” on August 4, 1944, presumably in Auschwitz, Poland, and a death certificate was issued. On January 28 of the same year, his death was entered into the municipal registers in Mareuil, in the Charente department of France, which was the last place he was known to have lived. The Mareuil town hall kindly provided us with a copy of the entry in the register. We imagine that the official acknowledgement of Justin’s death helped his uncle to grieve for his nephew and perhaps even to deal with his brother’s estate.

Justin Wiesel’s death certificate, dated January 14, 1947 (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen and copy of the entry in the municipal register in Mareuil, in the Charente department of France

This file includes some information about Justin’s disappearance, as well as some valuable insights into his life. However, as a result of our investigation, we have been able to add to and in some cases correct the details.

II. Justin’s early years in Thionville

We are now going to reconstruct Justin’s life story in more detail. Thanks to his birth certificate and his father’s residence record, both held in the Thionville municipal archives, as well as a census of Jewish refugees taken in Royan, in the Charente department of France on October 15, 1940, we have some insight into the Wiesel family’s life before the Second World War.

Justin’s parents were David Dub alias Wiesel and Catherine Auszemann, both of whom were Jewish hailed from Czechoslovakia. His father was born on May 26, 1900 in Velky Bokhov, in present-day Ukraine and his mother was born in Rahovo on March 11, 1902. This may be Rakhiv, a town some 22 miles from Velky Bokhov, also now in Ukraine. According to the census data for Royan, his parents left Czechoslovakia and moved to France in 1925 and 1928 respectively. However, we have no explanation as to why they arrived in France on different dates. Nor do we know where or when they met or got married, but it was neither in Thionville nor in Metz. According to his residence record, David moved to Thionville from Metz in 1931, but there is no record of him ever having lived in Metz. In Thionville, he was a tailor, working for the 168th Infantry Regiment, and his wife did not work.

Census of Jewish families carried out by the Royan town council, listing Justin’s parents’ details and their dates of arrival in France (Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

David Dub alias Wiesel’s residence record (Thionville municipal archives)

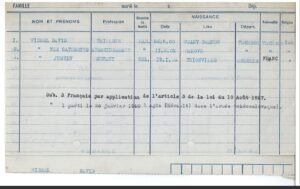

In 1933, the couple were living at 34 rue du Maréchal Joffre in Thionville, and Justin Wiesel was born on January 19 of the same year. He was born at 7 rue Laydecker, in the former Beauregard hospital, in the neighborhood of the same name. The residence record states that, in accordance with article 3 of a French law dated August 10, 1927, since his was born in France and at his parents’ request, Justin was granted French citizenship. He was an only child. We contacted the Jewish community in Thionville, but no one could remember the Wiesel family or David’s brother, Eizik, who appears to have moved into his brother’s old apartment after the war.

Justin Wiesel’s birth certificate, dated January 21, 1933 (Thionville municipal archives)

Eizig (or Eizik) Leib Wiesel was also born in Velky Bokhov on April 6, 1903. We found two residence cards for him in the Metz municipal archives. They reveal that he arrived there straight from his hometown in December 1926, and lived at several different addresses, including 11 rue du Pontiffroy in 1933-1934, where he apparently stayed with the Tabak family, which another class in our school researched last year. Léa Tabak, the mother of the family, who we shall come back to later, had lived in Rakhiv for several years, and got to know Justin’s mother while she was there. Eizik was single and worked in the ironing trade. We discovered that he left Metz in January 1940 but there is no record of where he went next. He was the uncle who, after the war, was responsible for having his nephew’s death documented. By that time, he was living at his brother’s previous address, but there is no trace of him after that.

Eizik Leib Wiese’s residence recordl (Metz municipal archives)

III. The move to Royan

When the Second World War broke out, Thionville’s proximity to Germany meant that it was in danger of being invaded. According to the Chemins de Mémoire website, the town was evacuated on May 10, 1940, although the areas closer to the border had in fact already been evacuated. The residence record does not list the date on which the family left Thionville, but it does state that on January 26, 1940 David left for Agde, in the Hérault department of France, to join the Czechoslovakian army.

In order to understand the background of this army, we need to go back to the Sudetenland crisis, the signing of the Munich Agreement on September 29 and 30, 1938, and the German invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939. These events prompted a large segment of the Czechoslovak political elite and military personnel to leave for France. In 1939, a Czechoslovak army was re-established in France, and in November of the same year, Czechoslovak citizens were mobilized. A camp in Agde, near the town of Béziers, was the main assembly point. It was at this time that David Wiesel was called up. In May 1940, the Czechoslovak army comprised at least 11,000 soldiers, who later took part in the Battle of France alongside the Allies.

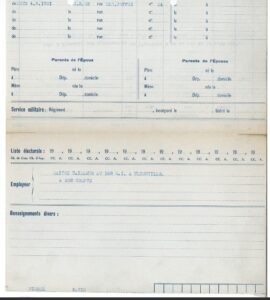

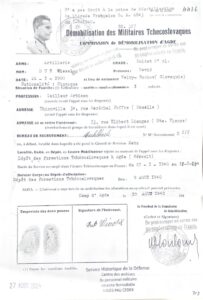

The Center for Military Personnel Archives in Pau, in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department of France, kindly provided us David’s service record, notably his demobilization form dated August 10, 1940. This states that David was a second-class soldier, that he had joined the artillery corps on January 27, 1940 and that when he was demobilized, he went to Limoges, in the Haute-Vienne department, where he lived at 13 rue Elibert. As a foreign national, he was not entitled to a demobilization allowance and nor was he allowed to work in France. This record is also the source of the photo of David.

Since the residence record does not list the date on which Justin and his mother left Thionville, we suppose that it was after David went to Agde. Perhaps they had to leave in great haste in May 1940, when Germany launched its blitzkrieg attack. This may explain why the town hall staff were unable to register their departure. They moved to Royan, a seaside resort in the Charente-Inférieure department, on the west coast of France, where a large number of Jews from Lorraine took refuge. On October 15, 1940, along with all the other Jewish people in the town, the family was registered during a census, as decreed by the Commander-in-Chief of the Military Authority for the Occupied French Territories. They were living in the Villa “Caseta”, on Avenue de la Triloterie in Royan. Catherine signed the census form, noting that her husband was “detained in the free zone as he had been mobilized”, and was therefore probably still in Limoges. This census was in fact carried out in preparation for the eviction of Jews from the Atlantic seaboard, which took place a few weeks later.

David Dub-Wiesel’s demobilization form dated August 10, 1940 (Defense Historical Service, Center for Military Personnel Archives in Pau,)

Wiesel family census record, Royan, October 15, 1940 (Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

IV. Life in Mareuil prior to the roundup

When the Jews were banned from the Atlantic seaboard, the Wiesel family was sent to a village called Mareuil in the Charente department, probably in November 1940. It is not known whether David had returned to his wife and son in Royan, or whether he was reunited with them in Mareuil. Eight other Jewish families were also assigned to this village, including the Tabak family, with whom David’s brother Eizik had stayed a few years earlier.

In his book Les Chemins pour l’enfer (The Pathways to Hell), Raymond Troussard, who compiled numerous eyewitness accounts, explains that the families were so well integrated into the local community that they did not even comply with the requirement to wear the Jewish star, which had been made compulsory by the Vichy regime in June 1942. Justin went to school in the village, as did his friends Joseph and Jacques Tabak.

It was in fact while the children were at school, on the morning of October 8, 1942, that four police officers arrived from Rouillac by bicycle. They went to see all of the Jewish families in Mareuil and asked them to assemble at the town hall which, as was often the case at the time, was in the same building as the school. They were then taken by bus to Angoulême.

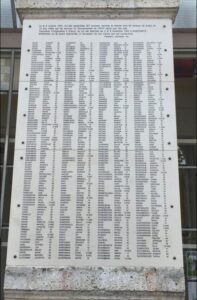

The memorial plaque commemorating the nine Jewish families arrested in Mareuil in October 1942. The old Mareuil town hall and school building. (source: Mareuil, Patrimoine de Cognac website)

Again according to Raymond Troussard, Justin was spared from being taken to Angoulême after the local schoolteacher, Jean Robert, intervened on his behalf, firmly objecting to his being taken away on the grounds that he was a French citizen. The head of the Belfis brigade therefore agreed to release him along with the other two French Jewish boys, Joseph and Jacques Tabak. Before he left, he even arranged for them to be placed with foster families. The two Tabak boys were placed with the Marolleau family, while the Mary family took in Justin. We tried to find this family in Mareuil but unfortunately we were unable to trace them. As for the teacher, he had all the pupils line up to say a final goodbye to their non-French Jewish classmates. And Justin, who was not even ten years old, probably never saw his parents again.

All the Jews from Mareuil who were not French citizens, including Justin’s parents, were taken to Angoulême, the capital of the Charente department, where they were gathered together in the Philharmonic Hall. According to a commemorative plaque unveiled in 2012, a total of 387 Jews were rounded up in the Charente region on October 8, 1942. Almost all of them were transferred to the Drancy internment camp on October 15, then deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau aboard Convoy 40 on November 4, 1942.

Commemorative plaque in honor of the victims of the roundup of October 8, 1942, on the music school in Angoulême, formerly the Philharmonic Hall.

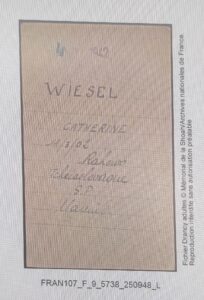

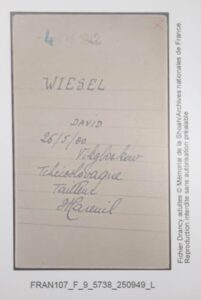

Drancy camp internment cards for David and Catherine Wiesel (Shoah Memorial, Paris).

We found the Drancy internment cards for David and Catherine, and their names are on the Convoy 40 deportation list. There is no further trace of David, which suggests that he died either on the way to Auschwitz or as soon as he arrived there. However, the Arolsen archives sent us Catherine’s death certificate, dated December 9, 1942, which states that she died of “pulmonary edema due to pneumonia”. This suggests that she was selected to work in the concentration camp but only survived for a month. This was the average life expectancy for a prisoner at Auschwitz. She most probably died as a result of the abuse and appalling living and working conditions that she had to endure.

Catherine Wiesel’s death certificate, dated December 9 1942 in Auschwitz (Arolsen archives)

We have no idea how long Justin stayed with the Mary family. We do know that the Tabak boys stayed with two families in Cognac as of January 1943, and that they went to school there. Justin’s whereabouts during this period, however, are unknown. He probably stayed with a family in the Charente department, since he was transferred to Paris on June 9, 1943, at the same time as the other Jewish children in Charente.

V. The Lamarck center and deportation

According to Joseph Niderman’s testimony, as recounted by his brother Richard, on June 6, 1943, the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews) gave the order to transfer all Jewish children in the Charente department, including those in the free zone, to Paris. The children were initially rounded up in barns or function rooms in Angoulême, then sent to the Lamarck center in Paris on June 9.

The Vichy government, at the behest of the Germans, founded the UGIF on November 29, 1941. The idea was to make it easier to identify Jews and to form a separate national community in order to put an end to their integration into the French state system. It was also intended to provide assistance at a time when Jews were excluded from working in certain occupations and many roundups were taking place.

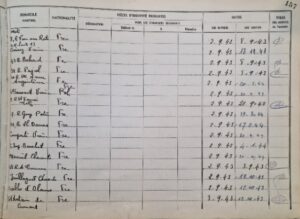

Justin Wiesel was sent to the Lamarck children’s home, UGIF center no. 28, where he was checked in at 5 p.m. on June 9, 1943. The home was located near the Sacré Coeur in Montmartre, in the 18th district of Paris, and it took in children after the major roundups in 1942, after which their parents were often deported. Foreign children and children born to foreign parents, such as Justin, were put on a list and were deemed to be “deportable” at any time.

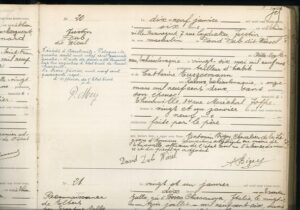

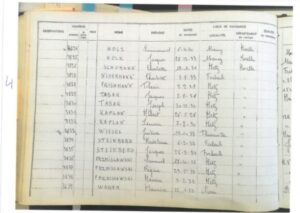

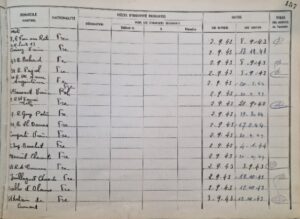

Pages from the Lamarck center register listing the names of children in the order in which they arrived, starting on June 9, 1943 (Montmartre Jewish center)

In the Lamarck center register, children were not listed in alphabetical order, but in order of arrival. Justin’s name is very close to those of the Tabak boys, suggesting that they were quite close and perhaps supported each other.

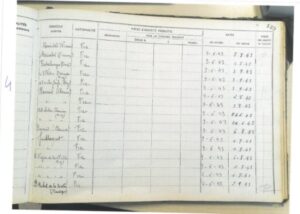

Official lists of children allowed to leave the Lamarck center “28” on Sundays, June 27, and July 4, 11 and 18, 1943 (Shoah Memorial)

On each of these Sunday outings, intended to give the children a sense of family life, Justin went to visit the Winterman family at 6 rue Félix Terrier. Joseph and Charlotte Niderman, both from Forbach, were always there too. There were several children in the Winterman family, including a daughter, Lucienne, who was also deported on Convoy 77 and who survived.

Records of Lamarck center outings, August 6, 1943 (Shoah Memorial)

On August 6, 1943, 4 days after the Tabak brothers, Justin and two other children left the Lamarck center to go to the Louveciennes center in the Seine-et-Oise department (now in Yvelines). The Louveciennes center no. 56, also known as the “Séjour de Voisins”, was a former agricultural orphanage that the UGIF had converted into a children’s home in the countryside. Many of the children from the Lamarck center were sent there on vacation during the summer of 1943.

On September 3, 1943, young Justin was taken back to the Lamarck center, along with Jacques and Joseph Tabak. Presumably, like many other children who were staying there the center, the three boys went to the Lucien De Hirsch school in the 19th district of Paris. The only known photograph of Justin, which appears at the top of this biography, was probably taken as part of his school records.

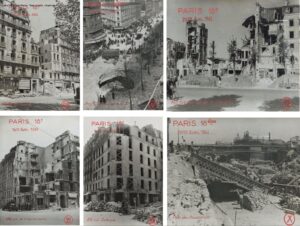

On April 20, 1944, a bombing raid on northern Paris destroyed part of the Lamarck home. As a result, a lot of the children, including Justin, were sent to another UGIF center, the Lucien De Hirsch school at 71 avenue Secrétan, which was then turned into a boarding school.

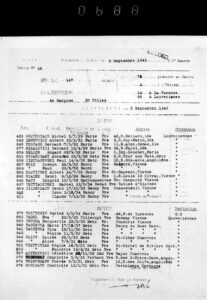

Record of arrivals and departures from the Lamarck center, September 3, 1943 (Shoah Memorial)

Photos of the damage caused by the Allied bombing in the 18th district of Paris on the night of April 20-21, 1944. (Photographic file commissioned by the Paris road engineering department, Louis Silvestre, Paris city archives)

Page from the Lamarck center register listing the date on which Justin returned from Louveciennes in September 1943 and his final departure from the home on April 21, 1944 (Montmartre Jewish center)

A few weeks before the Liberation of Paris, on the night of July 21-22 1944, roundups were carried out at six UGIF homes in and around Paris: Secrétan, Vauquelin, École du travail, La Varenne, Saint-Mandé and Louveciennes. All of the children were transferred to Drancy. Justin’s internment card states that he arrived there on July 22, 1944. He was assigned the number 25,397. The entry 6.2 in the transfer log refers to his placement in the camp, i.e. in dormitory 2 on stairway 6. The letter B, in blue, and the yellow band at the top of the card mean that he was subject to immediate deportation.

Justin’s internment card, from the Drancy children’s file, completed by internees supervised by the camp authorities (Shoah Memorial, French national archives)

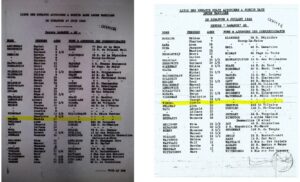

Page from the Drancy camp transfer book (Shoah Memorial, French national archives)

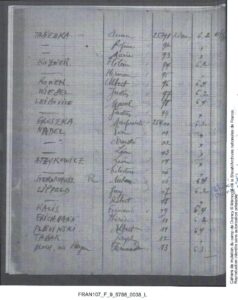

Pages from the Convoy 77 deportation list (Arolsen archives)

Together with the other children, Justin was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on convoy 77, which left the camp on July 31, 1944, just one week after he arrived in Drancy. The last mention of Justin is on the Convoy 77 list, but this list was not drawn up until after the war. We do not know the exact date on which Justin died, but he was almost certainly murdered in the gas chambers as soon as he arrived at Auschwitz. His official date of death is August 5, 1944.

ADDENDUM: June 2024, 12th grade class 7.

When we unveiled our research into Justin Wiesel and Rachel Eisenberg, which was carried out during the 2023-2024 school year, Alain Brunwasser, a cousin of Cécile and Simon Dembicer, brought this photograph, which belongs to his family, to our attention.

The photo was actually sent to our fellow students last year, when they were researching Cécile et Simon, but they overlooked it because neither the location nor some of the people in it meant anything to them. However, they did recognize Isaac and Rosa Dembicer, Cécile, Simon in the stroller and Abraham Sobel, the husband of Hélène Brunwasser, one of Rosa’s sisters. Given the children’s ages, the photo was probably taken in 1937 or 1938. The tailor’s store in the background was clearly not Isaac’s and the couple in the doorway were unknown, as was the little boy dressed very much like Cécile. There was some speculation that this might be one of the four Sobel boys, but no firm evidence.

Our research into Justin shed more light on the photograph. The name on the door of the store reads “Wies…”, preceded by a “D”. The store must therefore have belonged to David Wiesel, Justin’s father, who was a tailor in Thionville. He can be seen in the doorway, and we can assume that the woman beside him is his wife Catherine, although we do not know what she looked like. The little boy beside Cécile might well be Justin, as they were both the same age. If it is, it provides us with a second photo of him.

Although we cannot be sure that it is Justin and his mother in the photo, it nevertheless confirms the friendship that we felt must have existed between the Wiesel family and various members of the Brunwasser family. Catherine Wiesel was originally from Rakhiv, where the Brunwassers lived before they migrated to France. While she was living in Thionville, she kept in touch with at least three of the sisters who lived in Metz: Rosa Dembicer, Hélène Sobel and Léa Tabak. They all met up again later, when they fled to Royan. From 1940 to 1942, Catherine Wiesel lived near Léa Tabak in Mareuil; they were arrested there on the same day, and their sons only just escaped being arrested. A few months later, Justin, Joseph and Jacques were reunited with Cécile and Simon, Rosa’s children, prior to being deported on Convoy 77.

Français

Français Polski

Polski