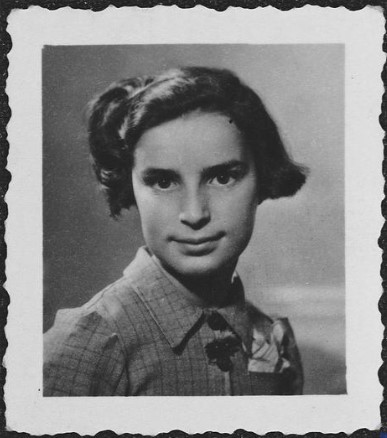

Rachel EISENBERG

Photograph of Rachel Eisenberg taken at the Lamarck UGIF home in 1943 or 1944 (Shoah Mémorial, Serge Klarsfeld collection)

Our investigation into the lives of Rachel Eisenberg and the various members of her family took us from the shetl of Nowy Zmigrod, in Poland, to Metz, their adopted city in the Moselle department of France, then to Royan in the Charente department and then to Saint-Michel-Léparon in the Dordogne department, where the twists and turns of history meant they had to move on, and subsequently to the UGIF homes and internment camps where they were detained as a result of the Vichy regime’s anti-Semitic persecution, only to be deported to Auschwitz, from which they never returned. We were also able to broaden our historical knowledge of the inter-war years, the Second World War and the Holocaust in particular. We learned about the historical research process as we examined numerous archived documents from the various places where the family members had lived. By cross-referencing these records and putting them into context, we attempted to reconstruct this tragic story.

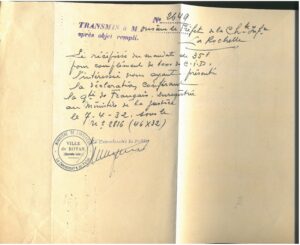

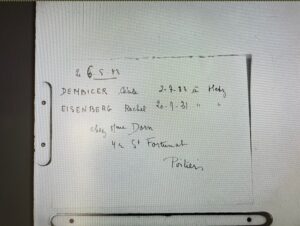

Rachel’s story is in part linked to that of Cécile Dembicer, whose life story another class at our school researched last year, which was a great help to us. Mr. Xavier Hallaire, a former deputy mayor of La Roche-Chalais, of which the village of Saint-Michel-Léparon is now a part, was also very helpful. He provided us with various material, in particular a little bundle of paperwork that a local resident had donated to the village council some years ago. The man had found the bundle in a barn at the house where the Eisenberg family lived during the war. It contained over forty documents, including some simple slips of paper, which between them provide invaluable information on the family’s life in Poland in the 1920s right through to their time in Royan in 1940.

Photo of the bundle that was found in a barn Saint-Michel-Léparon, in Dordogne.

I. A family originally from Nowy Zmigrod in Poland

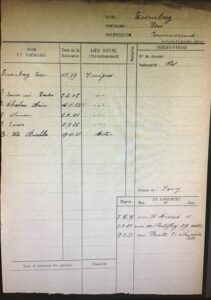

Iser Eisenberg’s residence record (Metz municipal archives)

Between 1883 and 1940, the towns and villages in the Moselle department of France kept a register of every household, detailing the family members, their marital status and any changes of address. The records for Iser (or Aser or Ojser) Eisenberg, Rachel’s father, are held in the Metz municipal archives. They show that he, his wife, Tauba Gross, and their three sons were born in Zmigrod, Poland. In fact, they were born in Nowy Zmigrod, a shtetl, or Jewish village, on the edge of the Carpathian Mountains, in the province of Galicia, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the population of the village was around a thousand, most of whom were Jewish. Mr. Bernard Flam, an archivist at the Medem Center in Paris, a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of Yiddish heritage and culture, kindly sent us a copy of an alphabetical list compiled from the Nowy Zmigrod Jewish registers.

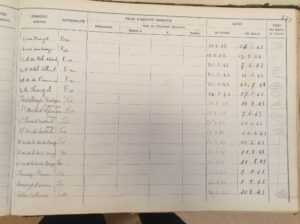

Pages from the alphabetical list taken from the Nowy Zmigrod Jewish registers: column U: births, column M: marriages, column Z: deaths (Nowy Zmigrod municipal archives)

These lists include a record of Iser’s birth in 1888. This is probably a mistake, since all the other records we have state that he was born on January 1, 1899. Tauba’s birth, however, is not listed, even though, later on and in France, she said that she was born in the same village on February 2, 1902. Their marriage in 19325 is also listed in (certificate no. 4), followed by the births of their sons Szymon in 1924 and Leizer in 1926. Oddly, however, the birth of their eldest son, Abraham Chaïm, who was born on November 16, 1922, is not listed.

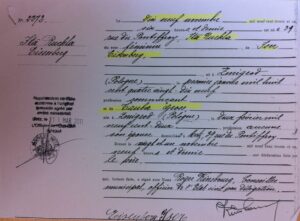

Among the papers from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon is a copy of their second son Szymon’s birth certificate. As it was in Polish, Véronique Chyla, a former pupil at our high school, kindly translated it for us. It confirms that Szymon was born on August 2, 1924 in Nowy Zmigrod, and says that his mother was also born there. It says that he was circumcised on August 9, when he was eight days old, in keeping with Jewish tradition. The witness to the circumcision was Leizer Gross, who may have been his mother’s brother. It also lists the names of his maternal grandparents, probably because the Jewish line is passed down from the mother’s side. Lastly, it states that Iser was a merchant and that Tauba sold eggs, as did Leizer, the witness. This suggests that the family was quite poor, which may explain why they later emigrated to France.

Szymon’s birth certificate (from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

II. The move to France and life in Metz

It was after their third child, Leizer, was born on July 5, 1926, that the Eisenberg family emigrated to France. When exactly they did so, however, is unclear. The census of Jewish refugees in Royan carried out on October 15, 1940 reveals that the entire family had been living in France since 1927. Iser’s residence record, meanwhile, says that he arrived in Metz in 1929. It just so happens, however, that there is a separate residence record for Tauba, which states that she arrived in Metz in 1928. Nevertheless, both records say that they moved there from Nancy, and both list their first address in Metz as 11 rue Saint Médard. Regardless of the exact date on which they left Poland, their reason for leaving was probably the economic problems in the country, which prompted some 800,000 Polish people to migrate to France, particularly to the Lorraine region.

Tauba Eisenberg’s residence record (Metz municipal archives)

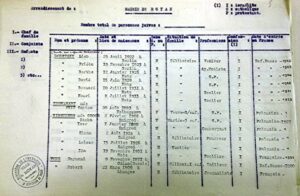

A page from the census of Jewish refugees in Royan taken on October 15, 1940

(Charente Maritime departmental archives)

During their time in Metz, the family lived at three different addresses. In August 1930, they moved to 29 rue du Pontiffroy. It was there that Rachel, who was registered under the name Ita Ruchla, was born on November 19, 1931. Lastly, in December 1933, perhaps because the family needed a bigger home, they moved to 81 rue Fleurette in the same neighborhood of Pontiffroy, the Jewish quarter in Metz. The family was therefore part of the city’s Jewish community, which is also reflected by the fact that their names are listed on the plaque commemorating the victims of the Holocaust in the Polish synagogue in Metz.

Iser was a travelling salesmen in the clothing, lingerie and hosiery sector. He sold his wares at fairs and on markets in the Moselle, Meurthe-et-Moselle and Meuse departments.

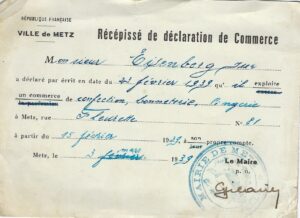

The bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon contains a number of receipts from Iser’s suppliers, as well as some proofs of payment of electricity bills and local taxes in the 1930s. We have no idea why Iser felt it necessary to keep these old receipts with his other, personal documents. Lastly, it appears that in February 1939, shortly before he had to leave Metz, he started his own business from home. At least, that is what the receipt for the declaration of his business, which was also found in the bundle, implies.

Copy of Rachel’s birth certificate;

(from the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy)

The commemorative plaque at the Polish synagogue in Metz

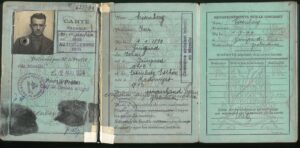

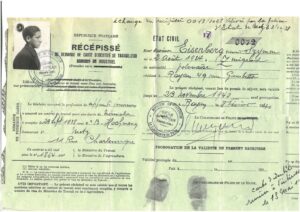

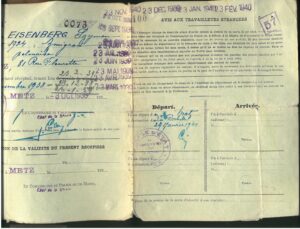

Iser Eisenberg’s 1933 foreign worker’s card, from an application for the renewal of his identity card (Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

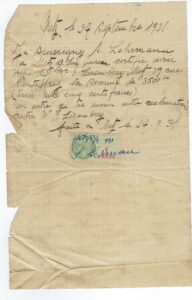

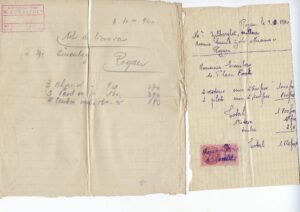

A receipt made out by a Mr. Lehrmann to Iser Eisenberg in 1931

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

Receipt for Iser Eisenberg’s business declaration, to take effect from February 15, 1939, issued on February 3, 1939

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

We know nothing about Rachel’s early years in Metz. All we know is that her parents applied for French citizenship on her behalf in April 1932, by virtue of a law passed in 1927. Her mother included a copy of a certificate to this effect in her application to renew her identity papers, which is held in the Charente-Maritime departmental archives. The granting of French nationality to a child born in France was very significant, as it could help the family avoid being deported. It also reflected the family’s desire to integrate into French society. Using the French versions of the children’s first names, which appear on numerous records, also illustrates the family’s willingness to integrate: Abraham Chaïm was called Charles, Szymon became simply Simon, Leizer became Louis and Ita Ruchla became Rachel.

Rachel’s certificate of French nationality, which was included in her mother’s application to renew her identity card

(Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

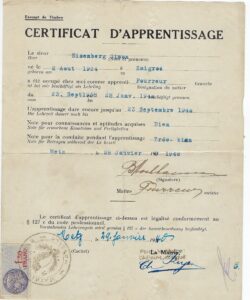

We have more details about Rachel’s brothers, in fact. From an apprenticeship certificate found in the bundle, we discovered that Simon was an apprentice furrier working for a Mr. Hochmann at 11 rue Charlemagne in Metz. He worked there from September 28, 1938 to January 28, 1940, when the family left the city. On his apprenticeship certificate, his employer noted that Simon’s work skills were “good” and his behavior “very good”.

Simon Eisenberg’s apprenticeship certificate issued on January 28 janvie, 1940 (from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

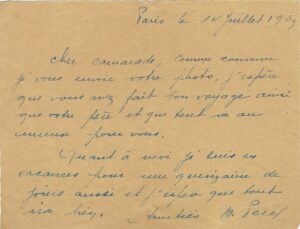

As for Abraham Chaïm, also known as Charles, we discovered from the bundle that he had serious health problems. On October 16, 1939, he was sent to the Boutillier sanatorium in Berck-Plage, on the coast in the Pas-de-Calais department. This implies that he was suffering from tuberculosis and had to spend long periods away from his family. The bundle also contains a short letter dated July 14, 1939, sent from Paris and addressed to a “comrade”. The writer hoped that the addressee and his father had had a good trip, and inquired after his health. It may well have been a friend that Charles had met on during a previous stay who sent him this letter.

Receipt for correspondence sent from Metz to Charles Eisenberg in Berck-Plage in October 1939

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

A letter that might have been sent to Charles Eisenberg by a fellow patient at the sanatorium, dated July 14, 1939 (from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

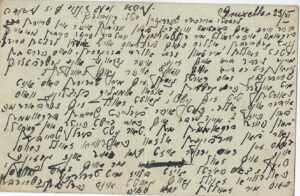

A postcard from his sister in Brussels, written in Yiddish also raises questions. With the help of Corinne Kalifa from COMEJD (the French National Council for the Memory of Deported Jewish Children), we had the card translated. It was written on November 29, perhaps in 1939, given that she expressed anxiety about news from “home”. If the card does indeed date from 1939, it must refer to the plight of the family in left behind in Poland, which Germany had occupied two months earlier.

Translation of the postcard:

Mr. Isser Eisenberg

81 Fleurette

Metz, Moselle

France

Brussels, November 29

Dear brother, sister-in-law and children,

You’re probably wondering who on earth could be writing to you.

I apologize for not writing before now. It was due to the resentment I felt over your last letter. We’ll forget all about that now.

How are you, my dear? Are you in good health and is business good? How are things at home? Are you still living in the same place?

As I write this card, my eyes are filling with tears. What has become of our home? Such a sudden calamity! May it never happen here! May G.od have mercy on you and on everyone.

Maybe you’ve had a letter from home? My dear, I’ve just received my first card from there.

We mustn’t write too much, but oh, if only it were true that everyone could be back home and in good health.

And I wish I could tell you that this card was written without tears.

If only G.od could help us all get together again soon.

We’ve also written a card to Poland. Greetings and hugs to you all.

From me, Devora and Chaim (?)

- S. Please write me how you are doing. Everyone here is doing well, thank G.od, and we’re earning enough to live on. Please reply soon.

Mr. Lerner

Rue Josaphat 149

III. A refugee family in Royan (January-Novembrer 1940)

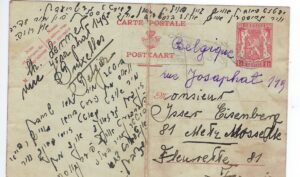

Rachel’s parents’ and her brother Simon’s identity card renewal applications, all three of which are held in the Charente-Maritime departmental archives, show that the family left for Royan on January 29, 1940, at a time when the people of Metz were being encouraged, although not obliged, to leave the area. On February 7, the refugee reception center notified the family that they 16 parcels had arrived for them from Metz. The parcels probably contained some of their belongings, which they had had sent on. The very next day, the family, who were then living at 49 rue Gambetta, set about rectifying their legal status. Sometime over the next few weeks or months, they moved to a new apartment at 10 place Foch.

Included in Iser’s application to renew his identity card is an undated letter from the Royan police department stating that he was unemployed, had no income, was living in free accommodation and was receiving a refugee allowance of 30 francs a day. It also states that he had written to the central Polish recruitment office in Paris. He may have wanted to join the Polish army that had been re-established in France at the end of 1939. Several receipts and invoices from suppliers, dated August to October 1940, found in the bundle, suggest that by then, Iser had resumed trading.

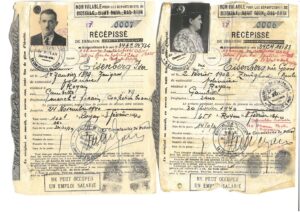

Page from Simon Eisenberg’s application to renew his identity card

(Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

Pages from d’Iser et Tauba Eisenberg’s applications to renew their identity cards

(Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

Notification from the Royan refugee center that it had received 16 parcels from Metz on February 7, 1940

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

Courrier non daté du commissariat de police de Royan concernant la situation administrative d’Iser Eisenberg et de sa famille;

(Archives départementales de Charente Maritime)

Undated letter from the Royan police department relating to the legal status of Iser Eisenberg and his family

(Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

A slip of paper with Iser Eisenberg’s name and address in Royan includes details of a German-French dictionary, which might possibly have been ordered from a bookstore. It is possible that Rachel’s parents, who had been speaking German and Yiddish in Nowy Zmigrod and in Metz, had to learn French when they arrived in Royan. Their children, on the other hand, probably spoke fluent French. Louis’ school certificate, written by his teacher at the Pelletan school in June 1940, suggests as much, since it says that he was a good student.

The note mentioning the German-French dictionary

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

Louis Eisenberg’s school report from the Pelletan school in Royan in June 1940

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

The bundle contains several other money orders sent from Royan to Charles between April and September 1940. Charles was still in Berck-Plage, but had moved to the Calot hospital. There is also a little note bearing the address of the Frères de Saint Jean de Dieu institute in Le Croisic, another place where Charles could have been treated. We contacted these various establishments, but they were unable to provide us with any information.

The family census form drawn up in Royan on October 15, 1940 lists Iser as having “3 children + 1 deceased”. Charles must therefore have died sometime between September 13, when the last money order was sent to him, and October 15. We have been unable to determine the date or place of his death. He did not die in Metz, Royan, Berck-Plage or Le Croisic, so maybe it was on his way home to the family, or somewhere between two sanatoriums. This census record is the only proof we have of his death. It was also used in the run-up to the expulsion of Jewish families from the Atlantic seaboard, which took place in November 1940.

The last letter sent from Royan to Charles at the Calot institute in Berck-Plage on September 13, 1940 (from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

The slip of paper with the address of the Frères de Saint Jean de Dieu hospital in Croisic

(from the bundle found in Saint-Michel-Léparon)

Iser Eisenberg’s personal census form, drawn up in Royan on October 15, 1940

(Charente-Maritime departmental archives)

IV. Relocation to Saint-Michel-Léparon (1940-1942)

Along with all of the other Jewish refugee families on the Atlantic coast, the Eisenbergs had to move on in November 1940. They were sent, along with eight other families, to the little village of Saint-Michel-Léparon in the German occupied part of the Dordogne department. The Dembicer family was sent to the neighboring village of Saint-Michel de Rivière. Both villages are now part of La Roche-Chalais, where memorials were unveiled on October 8, 2022, 80 years to the day after the roundup during which people were taken to the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême. Prior to the ceremony, Xavier Hallaire, the deputy mayor, and historians from the Shoah Memorial had carried out a two-year investigation. Local schoolchildren were also involved in this research. However, no specific information about the Eisenberg family emerged.

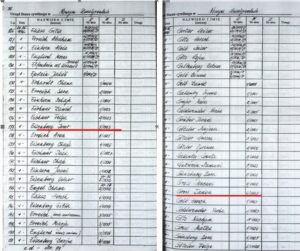

It was only during this investigation that the bundle was handed over to the town hall. Yet, oddly enough, it contains nothing at all about the time the family spent in the village. Incidentally, on September 22, 2022, Rachel’s photo was used in article in the Sud-Ouest daily newspaper about the unveiling of the memorials. Another trace of the Eisenbergs’ stay in the village appears in a notebook kept in the old town hall. It documents the delivery of yellow stars to all of the Jewish families in the village, in triplicate. For example, a family of five was given 15 stars over two visits, on June 6 and June 12. In line with rationing policy, this cost them 5 textile vouchers (one per person). One last detail about Iser and his two sons can be found on the Convoy 40 deportation list, which says that all three of them were deported on November 4, 1942. Compiled after the war from the Drancy internment records, it states that all three had been day laborers at Saint-Michel-Léparon, meaning that they were farm workers paid by the day. The family was therefore clearly in a difficult financial situation during their stay in the village.

Photographs taken at the unveiling of the memorial at Saint-Michel-Léparon on October 8, 2022.

The photo of Rachel Eisenberg that appeared in the Sud-Ouest newspaper on September, 2022

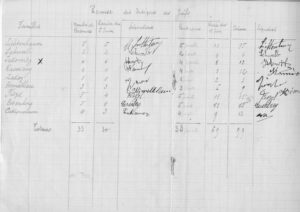

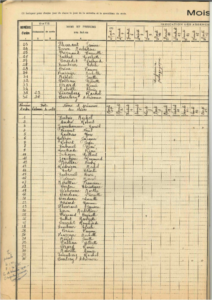

Pages from the notebook documenting the distribution of yellow stars to the Jews in June 1942

(Saint-Michel-Léparon municipal archives)

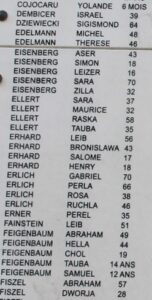

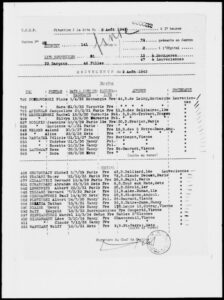

Page from the list of people deported on Convoy 40 on November 4, 1942 (Arolson archives)

V. A family torn apart during the Angoulême roundup (October 8, 1942)

The family’s new life in Saint-Michel-Léparon came to an abrupt end on October 8, 1942, when all foreign Jews from the German-occupied areas of Charente and Dordogne were arrested and taken to the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême. Iser and his two sons were held in Angoulême until October 15, when they were transferred to Drancy camp. From there, they were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 40 on November 4, 1942. Their names and ages are listed on the memorial plaque that was unveiled in 2012.

Part of the memorial plaque at the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême, commemorating the roundup that took place on October 8, 1942.

In Rachel’s case, this was because, as a French citizen, she was not subject to deportation at the time of the Angouleme round-up. We know from Mr. Robert Frank’s testimony that several French children who were arrested with their parents were released when the authorities were shown their identity cards. More surprising is the fact that Tauba was not arrested with her husband and sons. Was she away from home that day? Might she or her daughter have been sick? Did she manage to hide somewhere? We can only speculate as to what happened. However, in the nearby village of Saint-Michel de Rivière, Mrs Dembicer was not arrested and nor were her two children, as she was pregnant with her third.

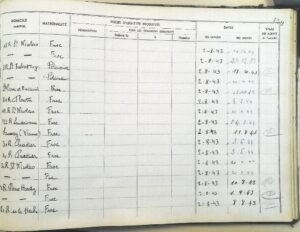

The next trace of Tauba is a month later, when on November 7, 1942, her name is listed in the register of the camp on the Limoges road in Poitiers, in the Vienne department. However, she only stayed there for a few days, since on November 13 she was transferred to Drancy, as her internment record testifies. She stayed there until February 11, 1943, when she was deported on Convoy 47.

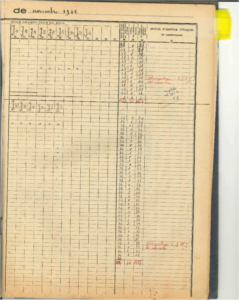

Page from the Poitiers camp register dated November 7, 1942

(Vienne departmental archives)

Tauba Eisenberg’s internment card from Drancy camp (Shoah Memorial)

We recently discovered that the school register for Saint-Michel de Rivière has been found. Rachel is listed in it as from October 1942. We also know that as of May 6, 1943, she and Cécile Dembicer were placed with the Dorn family, who lived at 4 rue Saint Fortunat in Poitiers. The Dorns, who were relations of the Decimbers, were also originally from Metz and had also fled first to Royan and then moved to Poitiers. That same day, Cécile was separated from her mother, who remained in the Poitiers camp with her newborn son. We can therefore surmise that Rachel stayed with the Dembicer family in Saint-Michel-de-Rivière from October 1942 to May 1943.

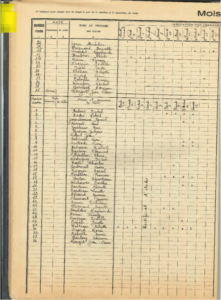

Registre d’appel de Saint-Michel de Rivière de novembre 1942;

(Archives municipales de La Roche-Chalais).

Registre d’appel de Saint-Michel de Rivière de mai 1943;

(Archives municipales de La Roche-Chalais)

A note that says that Rachel Eisenberg and Cécile Dembicer were placed with Mrs Dorn in May,1943 (Vienne departmental archives)

Rachel on her own

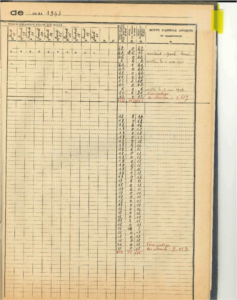

Rachel and Cécile are included in the list of 67 children interned in the Poitiers camp from May 24-26, 1943. Although the list is in alphabetical order, the girls are listed at the very end, as if their names were added at the last minute. It says they had been placed with the Dorn family, as had another child, David Amzel. On May 26, all of the children were sent to the Lamarck center in Paris, which was run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews). The Lamarck center register shows that Rachel stayed there until June 7. She probably then spent the summer at another UGIF home in Louveciennes, and, according to the arrivals and departures log, came back from there on August 2. She then left for good on February 8, 1944.

List of the 67 children interned in Poitiers camp from May 24-26, 1943

(Vienne departmental archives)

Register of arrivals at the Lamarck center on May 26, 1943

(Montmartre Jewish center archives)

Register of arrivals at the Lamarck center on August 2, 1943

(Montmartre Jewish center archives)

Record of arrivals and departures from the Lamarck center on August 2, 1943 (Shoah Memorial)

At that point, Rachel was probably sent to the UGIF home in Saint-Mandé, which was run by a woman called Thérèse Cahen. We do not know why Rachel was moved, in particular in the middle of a school year. The historian Jean Laloum wrote an article about Saint-Mandé in the journal Le Monde Juif (Jewish World) edition no. 155 in 1995. According to survivors’ testimonies, the children, the vast majority of whom were girls, were treated very kindly in this small, family-style home. Rachel’s name is on a memorial plaque, unveiled in May 2023 at the Paul Bert school in Saint-Mandé, which must have been the school she went to between February and July 1944.

The memorial plaque that was unveiled in May 2023 at the Paul Bert school in Saint-Mandé.

The last mention of Rachel is in the Drancy camp transfer book. She arrived there from Saint-Mandé on July 22, 1944, along with 18 other children and their supervisors. They were rounded up that day, as were all the children from five other UGIF centers in and around Paris, on the orders of Aloïs Brunner, who was in charge of Drancy camp. Rachel was assigned the number 25664 and placed in dormitory 2 on stairway 7, together with the other girls from Saint-Mandé. They were all deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

Page from the Drancy camp transfer book dated July 22, 1944

(Shoah Memorial)

Français

Français Polski

Polski