Laya RAFALOWICZ

Laja Rafalowicz was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. Her death, which was later officially declared to have taken place on August 5 of the same year, is listed in the death register of the 5th district of Paris.

We know nothing about Laja’s death other than that she was not yet twenty years old and had recently been rounded up in the UGIF home at 9 rue Vauquelin, in Paris, in the early hours of July 22, 1944.

The daughter of a family who had migrated to France

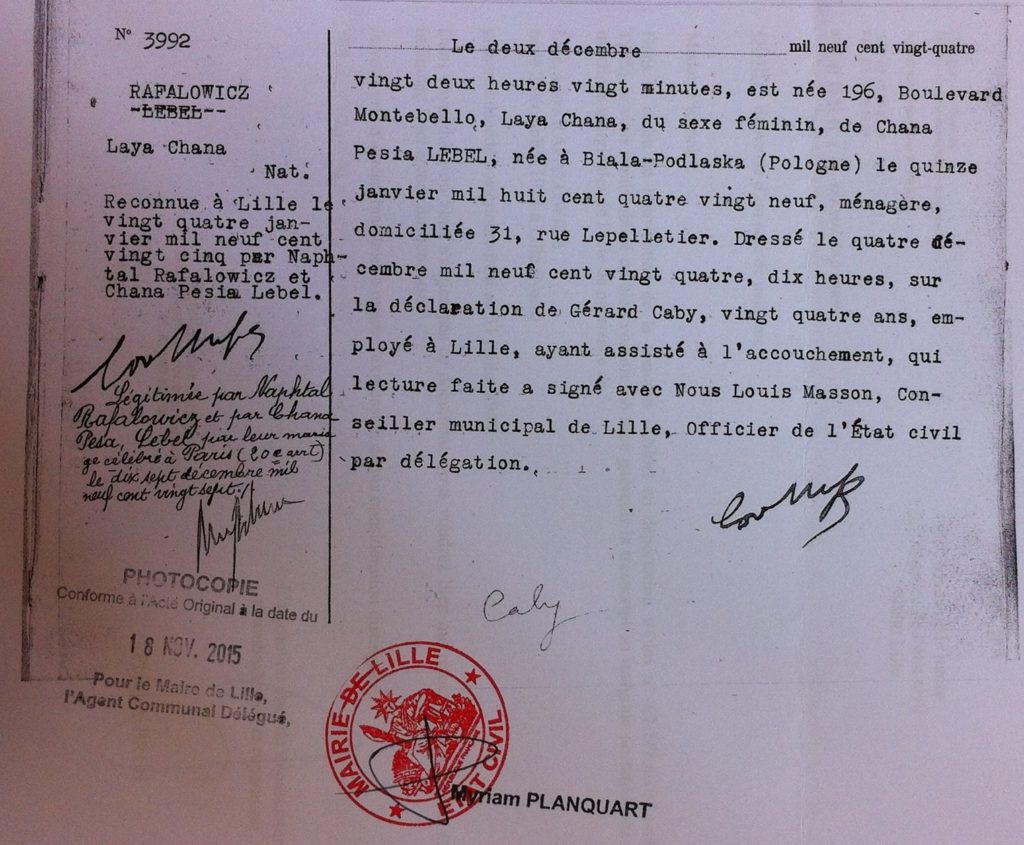

Laja Chana was born in Lille, in the Nord departement of France, on December 2, 1924. She was born in the Charité hospital, a huge building dating back to the Second French Empire, which has since been converted into a high school. Her mother, Chana-Pesia Lebel, who was born in Poland on January 15, 1889, was 35 years old at the time. When Laja was born, she was living at 31, rue Lepelletier, a little street in the heart of the old center of Lille, just a stone’s throw from the Place du Théâtre. Laja was officially recognized by her parents, Naphtal Rafalowicz and Chana, almost two months later, on January 24, 1925, also in Lille.

Laja’s birth certificate (RAFALOWICZ-Laja-DAVCC-21-P-482-375-4)

Laja’s birth certificate (RAFALOWICZ-Laja-DAVCC-21-P-482-375-4)

Two years later, on December 17, 1927, when her parents got married in the 20th district of Paris, Laja became a legitimate child.

A family originally from Poland

Naphtal Rafalowicz, who was born on September 28, 1895 in Kielce, Poland, was thirty-two years old when the couple got married. His father, Chaïa, was dead and his widowed mother, Chana Fajnkuchen, was still living in Warsaw, Poland. Laja’s mother, Chana Lebel, is listed on as having been born on January 6, 1889. Her parents were Abraham Joseph Lebel and Laïa Exhaus, both deceased. As we can see, first names, with slight variations in spelling, were passed down from one generation to the next.

Laja’s mother was born in Biala-Podlaska, a small town some twenty miles from Brest-Litovsk, then in the Russian Empire. The town had been home to a large Jewish community since the 17th century. Before the Second World War, there were 7,000 Jews living there, which was around 64% of the total population. Kielce, where Laja’s father was born, was also then in the Russian Empire. We can assume, therefore, that the family spoke mainly Yiddish, and no doubt some Polish and a little Russian too – who knows? At that point, in 1927, three of Laja’s grandparents had already passed away.

We do not know exactly when Laja’s parents arrived in France, but it may have been soon after the First World War, when France appealed to Polish workers to help rebuild the country, and large numbers of people migrated. The marriage certificate also reveals that Chana-Pesia, Laja’s mother, could not sign her name because she was unable to write. She is listed as a “housewife” on Laja’s birth certificate and had “no occupation” when she got married. Both of her parents were born in Poland, but their marriage certificate makes no mention of their nationality, so it is not known whether they were still Polish citizens or had become naturalized French citizens – at least in 1927. In any case, there is no trace of any application for naturalization in the records I found.

Laja’s parents’ marriage certificate © Civil register of the 20th district of Paris, Paris Departmental Archives

Laja’s parents’ marriage certificate © Civil register of the 20th district of Paris, Paris Departmental Archives

Life in Belleville, one of Paris’s poorest neighborhoods

Naphtal was listed on the marriage certificate as a laborer. At the time, the family was living at 10 passage Deschamps, in Belleville. One of the two witnesses to the marriage lived in the same building, at number 10, and the other lived next door, at number 12, where she ran a hotel. However, if the census records are to be believed, numbers 10 and 12 were probably one and the same building, a hotel (or boarding house/furnished rooms) which was occupied mainly by foreigners. It may even have been the one in the photo below. In any event, if the family really was living in passage Deschamps in 1927, they were not listed in either the 1926 or 1931 census.

A café-hotel in passage Deschamps, in the 10th district of Paris ©ruedupressoir.hautetfort.com. Passage Deschamps ran from N° 42 boulevard de Belleville to the rue du Pressoir, which itself included two dead end passages. It was in one of Paris’s most deprived neighborhoods, “îlot insalubre n°7” (insalubrious area no. 7). The entire neighborhood was razed to the ground in 1967.

In fact, the family remained in the same neighborhood, but moved to the nearby passage Ronce, also in insalubrious area no. 7, another of the streets in Belleville that was demolished in the 1960s. It was there, at no. 10, that one of the last survivors of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Esther Senot, lived. She described in her book La Petite fille du passage Ronce (The Little Girl from Passage Ronce ): “a narrow street where no cars passed, small low-rise buildings, with a store on the first floor and no more than two floors above that”. A few hundred yards away was rue Vilin, where the French writer Georges Perec spent his childhood, first at number 1 and then at number 24, and which he described in his semi-autobiographical novel W ou le Souvenir d’enfance (W, or the memory of Childhood). The Rafalowicz family first lived at 9 Passage Ronce, where they were listed in the 1931 census as Naftal and Chana and their two daughters, Laja and Ida. Laja’s younger sister was born in the same neighborhood on October 21, 1927, two months before their parents were married.

How long did they stay there? The census records for 1936 are only partially complete for this neighborhood, and the pages relating to passage Ronce are missing. They must only have moved a few doors down, however, because when Laja started school, the family was living at 9 passage Ronce, but when the Vélodrome d’Hiver round-up took place in 1942, all of them except Laja were arrested at 3 passage Ronce.

A page from the 1931 census of Paris: the family was living at 9 passage des Ronces. Nafta is still listed as a laborer and all of them are listed as Polish nationals.

Laja’s schooldays

Laja started school in 1931, on rue Etienne Dolet, which was not far from the little streets in Belleville.

Her name is listed in the enrollment register for the girls’ school at 31 rue Étienne Dolet in the 20th district of Paris. Her first name, Laja, is spelled Laya, as it was pronounced. It was then written in brackets as Léa, which sounded “more French”, while second name, Chana, was changed to Anna, probably for the same reason

I then found the name of her sister, Ida, who appears in the register for the first time three years later, in the 1934-35 school year.

Ida’s name in the school enrollment register

The school registers provide us with a little more information, some of it simply factual, some of it terribly blunt: in those days, the teachers’ comments in the registers were often quite harsh. But cruel as these comments were, they enable us to imagine what these two girls’ childhoods were like, and how they must have felt crushed in everyday life, even before they perished in Auschwitz. The teachers always noted that the parents were Polish, which again suggests that they had never applied to be naturalized as French citizens. It seems, however, that the teachers also changed the parents’ first names, not just those of the children: Naphtal is listed in brackets as “Max”, while his wife, Chana, is listed as “Anna” – the same change made to Laja’s middle name.

Raised in a poor family, living only on the father’s wages as a laborer in one of Paris’s most deprived neighborhoods, with an illiterate mother who hardly spoke a word of French, it is understandable that the girls were not exactly best placed to do well in school. Although children living in similar circumstances sometimes managed to blossom, accumulate knowledge, learn a trade or go on to further education… there was no sign that here.

Laja first went to the nursery school on rue des Maronites, a street running parallel to rue Etienne Dolet – in fact, the two schools made up one single unit, with their entrances on two different streets. They were just a stone’s throw from passage Ronce. Esther Senot, who was a year younger than Ida, went to a different school, on rue de Tourtille, a little further north in the neighborhood, but they may have bumped into each other in the street, and perhaps played together. Laja started “big school” on October 3, 1931. As for Ida, she did not go to nursery school at all, but went straight into elementary school on October 1, 1934, by which time she was nearly 7 years old. For Ida, things did not go too badly: when she left school in August 1939, just before she turned 12, she had at least completed her 2nd year of elementary school (although she had been in school for five years in total), and was described in the register as a “sickly child”, suggesting that she may have been absent a lot of the time. The comments continued, some positive, such as “sensible, pleasant character” and some negative, “of no intelligence, very slow”. For Laja, however, the elder of the two sisters, the assessment was all the more tragic as it hinted at a stark, gloomy future for the young girl: when she left elementary school in July 1938, after seven years there, she was still in 2nd grade! There was nothing positive in her teacher’s comments: “unintelligent, abnormal even, a rather difficult character”. Imagine that, a girl of nearly 14, in second grade, in a class of children of just 7 or 8…

What became of the girls after that? In June 1940, when the Germans marched into Paris, Ida was 12 years old. Legally, she should still have been in school, but maybe she was too sick, or weak, to go. Did that mean she was sent out to work? Probably not; perhaps she was bedridden. But what about Laja? By 1940, she was 16 years old, but what could she do? What kind of work might she have been able to get, given her apparent limited ability?

Alone in Paris. How did Laja avoid arrest during the Vel d’Hiv roundup?

These were terrible years for the residents of passage Ronce, where not only the Rafalowicz family but also four other people were arrested at number 9, five (the Senot family), at number 10, seven at number 11, sixteen at number 12, four at number 14, one at number 16 and three at number 18.

Esther Senot recounted what happened on July 16, 1942 as follows: “Uniformed policemen ruthlessly dragged our neighbors out of the houses across the street. We knew some of them, at least by sight. Most of them were Polish, like us. We soon realized that they were rounding up all the Jews”. On July 16, 1942, during the Vel d’Hiv roundup, 47-year-old Naftal (unless he was actually 55, his exact details remain a mystery), 53-year-old Chana and 14-year-old Ida were arrested.

Laja escaped, but it is not clear how. Might she have hidden in the attic? In a cupboard? In a neighbor’s apartment? Was she somewhere else that day? She could have been out at work, because in those days, young girls of 17 had no choice but to work. How much did she know about what was happening? Did she try to find her parents, or her sister? Time was running out. The first transports of Jews from the Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter Cycling track) took place on July 19. Between July 19 and 22, seven trains, operated by the SNCF (the French national rail company) transported more than 8,000 people from the Austerlitz station in Paris to the camps in Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande, in the Loiret department of France. The trains were made up of cattle cars to transport the Jews, with three passenger cars for the soldiers escorting them.

After they arrived in Pithiviers, what happened next? The Shoah Memorial in Paris has a deportation record for a Naptal Rafalowicz – Naptal, rather than Naphtal – a laborer, also born in Kielce but in 1887 – 1887, rather than 1895 – who was deported from the Pithiviers camp to Auschwitz on July 31, 1942 on Convoy No. 13, soon after the Vel’d’Hiv round-up. The Yad Vashem records give the same birth year, (1887) and also the names of his parents and his wife. This was definitely him then, although he had apparently aged a few years. Another source, a French decree dated March 3, 2011, relating the addition of the words “Died during deportation” to death certificates, cites the name of Naftal Rafalowicz, who died on August 30, 1942 in Auschwitz and was born on September 28 in Kielce, but this time the birth year is listed as 1886. This illustrates just how difficult it is to trace such deaths, eighty years after the events took place.

And what about Chana, the girls’ mother, what became of her? Was she deported on Convoy 16, along with her younger daughter? Or on Convoy 13, with her husband? On Convoy 14 from Pithiviers or Convoy 15 from Beaune-la-Rolande? On the Yad Vashem lists, I found a Chaja Rafalowecz – neither Chana nor Rafalowicz – born in 1899, rather than 1889, but on January 6 (the same date as that on her marriage certificate, January 6, 1889), and in Vialo, rather than Biala-Podlaska – but then again, to a police officer in a hurry, these Polish village names probably all sounded very similar, as did the family names, especially when spoken by an illiterate Polish Jewish woman. This “Chaja”, who was deported from Pithiviers on the same Convoy 13 as “Naptal”, was no doubt Chana, and thus the parents were deported together, he as number 38 on the deportation list and she as number 167. Their younger daughter was left behind, all alone, in the Pithiviers camp.

Ida too, like her father and mother, was deported from Pithiviers to Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to the original deportation convoy list, she was detained in barrack number 12 before being deported under the name of Hida on Convoy 16, which left Pithiviers at 6:15 a.m. on August 7, 1942. When Convoy 16 was ready to leave the camp, and as the German authorities had not yet agreed that children under the age of sixteen could be deported, many children were separated from their parents at the last minute, which made for some heart-wrenching scenes. But then, the Orleans police chief announced that children over 12 who looked older than that could also be deported: Ida, a sickly child of nearly 15, was no doubt one of them Of the 1,069 people deported on this convoy, all of them Jewish, 864 were women and children, 300 of whom, including Ida, were under 18. The train made its way through Malesherbes, Montereau, Troyes, Brienne le Château, Montier en Der, Saint-Dizier and Bar-le-Duc, with the French military acting as escort until it reached the German border. It then continued on through Saarbrücken, Frankfurt, Dresden, Görlitz and Katowice. When the deportees finally arrived in Auschwitz on August 9, 795 of them were sent immediately to the gas chambers and murdered, leaving only 63 men and 211 women alive to enter the camp to work.

Laja’s time in the children’s home on rue Vauquelin, and the roundup

What then, became of Laja? Who was there to help her? Where did she stay during this time? How much did she understand about what was happening? I guess that when she got back to passage Ronce, after the roundup, she found that the door to their apartment had been sealed up. As Esther Senot described it: “There, before me, was a label attached to a bit of string and some wax. It was the first time I’d ever seen a seal.”

And what about her time in the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) shelter on rue Vauquelin? Laja’s name is not on the list of “internees” compiled in July 1943: we have no way of knowing when or how she came to be there. She was 19 in 1944, and from what little we know of her, we can only wonder if she was up to the task of supervising the younger children, as other girls of her age did. Perhaps her intellectual limitations meant that she was best suited to life as a boarder, a child in a young woman’s body… But who knows, whatever her teacher may have said about her in 1939, perhaps looking after children was her true vocation.

Clearly, the reason Laja found herself alone in the UGIF shelter at 9 rue Vauquelin was that she was separated from her parents during the Vel d’Hiv roundup, but perhaps she also gradually lost touch with the people she knew and could turn to for support, such as friends, relatives, neighbors, a concierge, who knows? We shall never know how she coped during those six months in 1942, the whole of 1943 and the spring of 1944, until that fateful summer night when Aloïs Brunner set about rounding up all the children in the UGIF homes in and around Paris.

Internment in Drancy

Now we come to what happened on rue Vauquelin, on the night of July 22, 1944. The men who raided the building were Germans, perhaps backed up by some French policemen – witness accounts differ on this point. They arrived very early in the morning, before 5 a.m., while it was still dark. They rang the bell and Frieda Kohn, the janitor, opened the door. One of the supervisors – we don’t know who she was – woke the children up and told them that the Germans were there. The girls were gathered together in the hall, where, as Yvette Lévy recalls, one of them had an epileptic fit. They were then loaded into a tarpaulin-covered truck, with two black Citroen Traction cars escorting them, and taken to Drancy camp, north of Paris. Along the way, they sang French scout songs, the Marseillaise and the Internationale: it was important not to give up hope, the survivors explained. Did Laja sing along with them?

The children from other UGIF homes were all rounded up on the same day and they arrived at Drancy within hours. All these children, Laja included, were held at Drancy for ten days. There, the group was split between several locations, between staircases 6 and 7, with separate rooms for men and women. Laja was sent to room 3 on staircase 6, with the managers of the home, Mrs. Mortier (Germaine Israël née Joseph) and Mrs. Camille Meyer, as well as the janitor, Frieda Kohn, and a small group of teenage girls. They were not allowed to go outside or play with the other children, who were staying in rooms with their instructors, except to go down to the latrines, which were known as the “red castle”.

Laja left Drancy for Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on the morning of July 31, 1944. She was one of thirty-three girls who were arrested in the home on rue Vauquelin. The 1,300 or so deportees were assembled in the camp courtyard, then divided into groups of 50 and loaded onto buses bound for the Bobigny train station. The journey to Auschwitz lasted three days and three nights. The prisoners travelled in cattle cars, with up to 100 people per car, with two buckets, one containing drinking water and the other for “their needs”. The door was opened only once along the way, to empty the bucket. The smell was unbearable and it was scorching hot in the wagons.

The arrival in Auschwitz

In the early hours of August 3, 1944 the train finally came to a halt at the far end of the Auschwitz-Birkenau ramp, between crematoria numbers 2 and 3. The girls from rue Vauquelin were separated into two groups: ten of them were selected to stay in the camp and work, while the rest were sent straight to the gas chambers. Yvette Levy later described the little group of girls gathered around the manager of the home, a white-haired lady, as they got off the train. This is how I first envisioned Laja, panic-stricken and clinging to the last person in the world she had left and still trusted. But no, maybe it was the other way around: might it have been that the children she cared for trusted her, and although she was young and probably fit enough to work, she refused to abandon them?

Sources

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen (DAVCC) dossier ref. 21 P 482 375

- Drancy transfer log book (F 9 5788)

- Paris departmental archives: civil registers, census records, school records (2811W 5).

- Yad Vashem archives

- Esther Senot’s book, La petite fille du passage Ronce, (the little girl from passage Ronce) published by Grasset, 2021

- Yvette Lévy’s testimony (Shoah Memorial, Paris, made available online on September 15, 2016)

Français

Français Polski

Polski