Maurice ADATO

Maurice Adato was just about to turn 19 when he died at the end of July 1944. Will we ever find out exactly what happened to him?

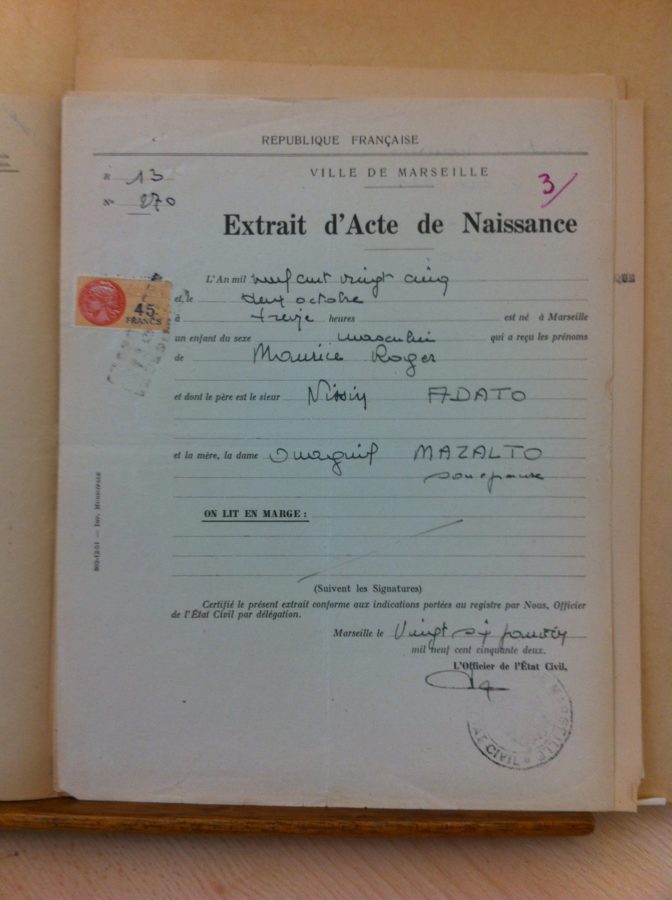

Since there are no photographs of Maurice Adato available, the image to the left is a copy of his birth certificate.

An official statement from the French Direction des statuts et des services (Department of statuses and services) dated February 27, 1961, certifies that Maurice Adato was interned on July 21, 1944, at the Drancy camp under the registration number 25342 and that he was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, on convoy No. 77.

Maurice Adato was born on October 2, 1925 in Marseille, in the Bouches du Rhône department of France. His parents were from the Ottoman Empire. His mother, Mazalto Ouaquil, was born in Constantinople in 1902 and his father, Nissim Youda Adato, was born in Andrinople in 1892. Nissim was the son of Yassef Adato and Esther. HIs first name suggests that he was a member of the Jewish community. This couple had three children: Youssef, born in 1920 in Constantinople, Esther, born in 1922 and also in Constantinople and Maurice, born in 1925 in Marseille.

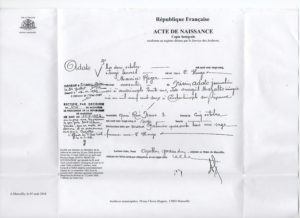

The record below is a copy of Maurice Adato’s birth certificate, which was provided by the Marseille municipal archives service. It also includes a record of a legal judgment issued in 1962, which determined that he died on July 31, 1944 in Drancy. However, if you read the typed information, it says that Maurice Adato died after having been deported to Auschwitz, on August 6, 1944. This correction was made in 2004 and was transcribed into the Civil Status register in 2006.

Current borders between countries

It is not known exactly when the family migrated to France, but it was between 1922 and 1925, at a time when the Ottoman Empire was being restructured at the end of the First World War and when present day Turkey came into existence. They arrived in France by boat, at the port in Marseille, where Maurice Adato was born.

Maurice Adato’s parents were married on June 8, 1935 in Champigny-sur-Marne. The family then moved to 46 rue René Boulanger in the 10th district of Paris, in the Seine department. This was also Maurice Adato’s last known address. Having been born in France, he became a French citizen on August 13, 1935 by declaration before the Justice of the Peace in Nogent-sur-Marne (according to a law dated August 10, 1927). He was described as a “fitter” at the time.

How did the Adato family live through the collapse of France and the subsequent German occupation? How did they escape the roundups in 1942 and the anti-Semitic abuse perpetrated by the Nazis and the French collaborators? Was Maurice Adato involved in any Resistance activities? 75721 French Jews were deported to the extermination camps.

Maurice Adato was arrested “on racial grounds”, on the Boulevard de Strasbourg, in Paris, around 7 p.m. on July 21, 1944 and was interned in Drancy camp under the registration number 25342.

Was Maurice Adato deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77? In any event, he disappeared, and his family had no further news of him after he was arrested.

After the war, from 1949 onwards, various investigations were carried out: it became necessary to establish his legal status as a “non-returned person”. Esther Alexandre, Maurice Adato’s sister, requested a deportation certificate for both of her brothers: Maurice and Joseph (Youssef). A Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War record dated February 9, 1952, states that the ” Police commissioner at Porte Saint Martin certifies that Maurice Adato has not been seen since July 1944″. A missing person’s certificate, file number 76502, drawn up on January 29, 1953, states that Maurice Adato was interned in Drancy on July 21, 1944 and that he was deported to Auschwitz.

The complexity of the post-war environment is evident here. It was difficult to find out exactly what had happened to all the people who had been relocated or deported or had disappeared or died. The archives show that the “Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War”, the “Delegation of the Civil Status and Research Department”, the “Bureau of Deported Persons’ Civil Status”, the “Recruitment and Statistics Department”, the “Statuses and Medical Services Department”, and the “High Court of the Seine department” all investigated and exchanged information about what had happened to Maurice Adato, insofar as possible, based, for example, on a statement made by the “Police Commissioner of the Porte Saint-Martin”.

On October 11, 1955, the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War granted Maurice Adato the title of “political deportee” although the date on which he died remained unknown. It acknowledged that Maurice Adato had been interned in Drancy camp from July 21 to July 30, 1944, and deported on July 31 until August 5, 1944. On October 17, 1955, the Ministry issued card no. 1.1.75.07531 to his mother, Mazalto Adato, who was his legal heir (his father having died on November 1, 1955).

It is interesting to note the vocabulary used at the time: we come across the terms “racial deportee” and “political deportee”. What do these phrases actually mean?

When the conflict ended, the term “deportation”, which had emerged during the war, became firmly established and was used to refer to a wide range of groups of people, including prisoners of war, Compulsory Work Service deportees, those deported to concentration camps and/or because they were Jews.

The organizations involved in repatriation, the political parties and the media all suggested that associated everyone who had been repatriated with having been martyrs for their country. The deportees themselves did not necessarily identify with the prevailing patriotic narrative, which conflated deportation with resistance, even if they shared the values that it represented. As far as the political community was concerned, the Jews, who were deported on the grounds of their supposedly “racial” origins, barely figured in this version of events.

It was not until 1948 that the ambiguous meaning of the word “deportation” was clarified through legislation that distinguished between “resistance fighters” on one hand, and “political deportees” on the other, and excluded other groups (such as compulsory service workers and people “deported” according to criminal law). From then on, the term “deportee” was no longer used to mean population movements, but instead to refer to the transportation of people to German “camps”, without any specific distinction being made between such camps.

http://liberationcamps.memorialdelashoah.org/jalons/construction_memoire.html

Maurice Adato’s status as a “political deportee” entitled his family to receive financial compensation. The Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War awarded Mazalto Adato 12,000 French francs, which she was sent on June 12, 1956, in recognition of the loss of her son as a political deportee. At the time of writing, she still lives on rue Boulanger in the 10th district of Paris.

A judgment issued by the High Court of the Seine department on September 28, 1962, nevertheless declared that Maurice died on July 31, 1944, in Drancy, and this was transcribed into the Paris and Drancy town hall records on November 13, 1962. The court also advised the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs of its decision. A stamp, dated May 15, 1964, reads “Died for France”.

It remains unclear on what evidence the court based its decision about Maurice Adato’s date of death.

The term “Died for France” is questionable. In fact, during the post-war Gaullist era, it became difficult to distinguish between the remembrance of the Jews and that of the Resistance.

The glorification of the image of the deported Resistance fighter and the inclusion of the Jews in the broader category of “political deportees” also contributed to the erosion of the singular fate of the Jews.

http://liberationcamps.memorialdelashoah.org/jalons/construction_memoire.html

As we come to the end of this biography, it is impossible to say exactly what happened to Maurice Adato after he was arrested and interned in Drancy on July 21, 1944. Officially, Maurice Adato should not be counted among the people deported on Convoy 77, which was the last transport to leave Drancy for the Auschwitz killing center, but are we really sure about that?

Below is a drawing by Manon Quemin, an 11th grade literature syllabus student, who portrays Maurice Adato as a faceless figure. Manon is taking art classes and would like to continue her education in this field.

Français

Français Polski

Polski