Maurice FRANKFOWER

This biography was researched and written by the 9th grade students of the “Badinter” class at the Marais de Villiers middle school in Montreuil-sous-Bois, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department of France, with the guidance of their history and geography teacher, Claire Bertrand.

We initially began the project during the 2019-20 school year, but the COVID-19 epidemic stopped us in our tracks. At that time, we had very few resources available to us. During the 2022-23 school year, therefore, the project was relaunched, with the aim of gathering together additional records and searching for any possible descendants. Having written a Facebook message to everyone we could find with the name Frankfower in June 2022, Carole, the daughter of one of the survivors, contacted us in August that year. With the extra records and Carole’s help, our task became easier, although there still remain a few unresolved issues.

We are delighted to be able to share our work with you here.

A family of Polish descent

Fanny – Rosa – Sarah

Gitla – Gypojiale (the mother) – Perla – Jacob – Wolf (the father)

Joseph

Source: Family photo kindly provided by Carole Frankfower, Wolf and Gypojiale’s granddaughter

Taken in around 1930-1931

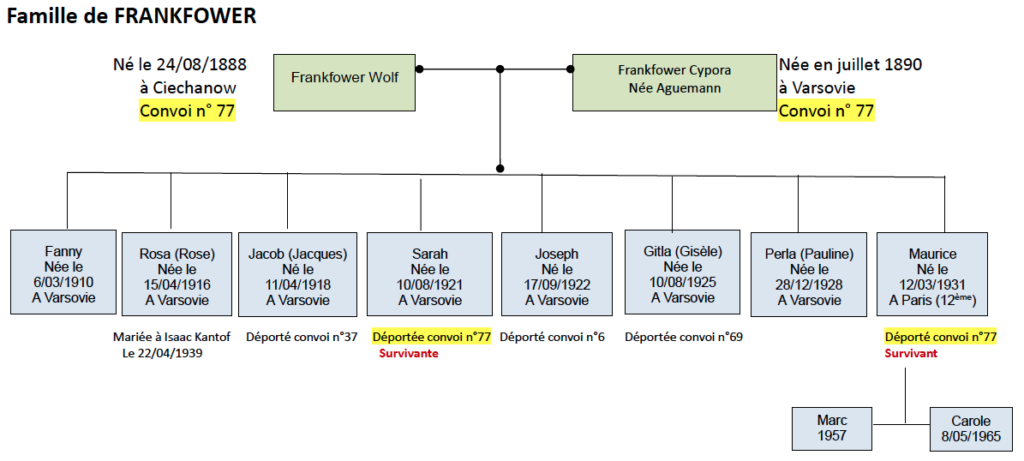

Maurice’s parents were both born in Poland, as were his siblings.

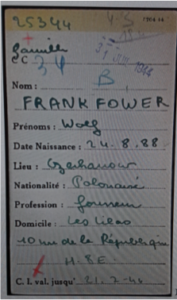

Wolf Frankfower was born on June 24, 1888 in Ciechanow (also spelled Créchanow on some records), a small town of around 5,000 people some 50 miles north of Warsaw. His parents were Samuel and Freja Bicaze, both of whom were Polish citizens and Jewish.

The town of Ciechanow in around 1910

Source

Wolf met and fell in love with Gypojiale Aguemann, who was born in Warsaw on June 28, 1890. Her parents were Radine and Bassa Crikman. Wolf and Gypojiale (again, the spelling varies) were married on March 28, 1909, also in Warsaw.

Warsaw in around 1900

Source: vanupied.com

The couple had eight children, seven of whom were born in Warsaw: Fanny, on March 6, 1910; Rosa, on April 15, 1916; Jacob (Jacques), on April 11, 1918; Sarah, on August 10, 1921; Joseph, on September 17, 1922; Gitla (Gisèle), on August 10, 1925; and Perla (Pauline, Paulette) on December 28, 1928.

Their last child, Maurice was born in the 12th district of Paris on March 11, 1931.

The move to France

Wolf Frankfower moved to France on November 26, 1929. He arrived legally, having been granted a visa. We are not sure whether the rest of the family arrived at the same time as the father, and nor do we know what prompted the Frankfowers to leave their homeland. We wonder if they were victims of pogroms, or living in poverty.

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte.

Photograph taken in December 2022 by Claire Bertrand

The family set up home at 10 rue de la république in Les Lilas, a working-class neighborhood of single-story brick houses. They were designed by the architect Emile Cacheux, a French public housing specialist. The houses he designed were built in the 1870s.

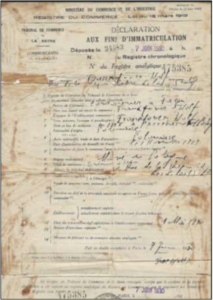

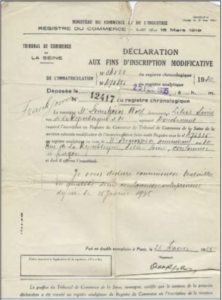

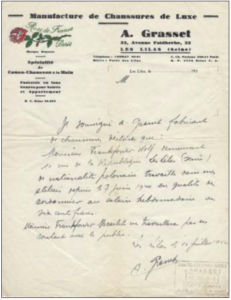

A few months after he arrived in France, Wolf became a shoemaker. He registered on May 1, 1930 and the Commercial Court officially declared him as such on June 7, 1930.

A second declaration, made in February 1935, confirmed that he was an independent shoemaker.

Source: Carole Frankfower’s personal records

It was in this blue-collar environment that the family’s last child, Maurice, was born in March 1931.

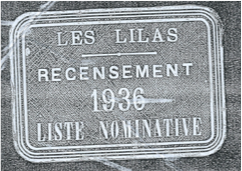

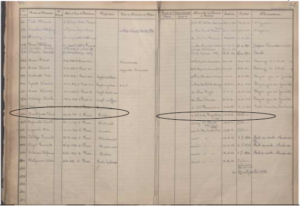

According to the 1936 census of Les Lilas, the entire Frankfower family, with the exception of the eldest child, Fanny, all lived in the same small, working-class house. They were still there during the Occupation, when some of the family were arrested, victims of the French government’s wartime policies (more on this later).

Les Lilas municipal archives

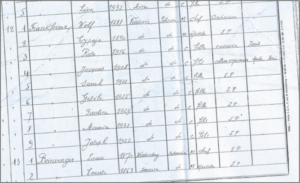

It appears that by April 1934, the family had decided to make France their permanent home, as Wolf Frankfower applied for French citizenship for himself and his wife.

The application was turned down, although there was no shortage of evidence of their willingness to integrate into French life. As shown on the 1936 census list, the children’s first names were all changed to similar French names. For example, Jacob became Jacques, Gitla became Gisèle and Perla was called Pauline.

Then, on September 2, 1939, with the outbreak of war in Europe after Nazi Germany invaded Poland, Wolf Frankfower volunteered to join the French army, despite the fact that he was 51 years old. This too showed his commitment to France.

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

Life during the German Occupation

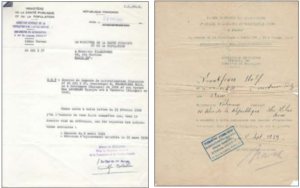

Wolf and his family remained in their home in Les Lilas. The Vichy government’s anti-Semitic policies introduced as of October 1940, meant that the father of the family could no longer continue to work.

Source: record kindly lent to us by Carole Frankfower

Having been registered as an independent shoemaker in 1935, he went on to work as a salaried employee in a shoe factory in Les Lilas. Was Wolf Frankfower forced to abandon his business, and were his assets confiscated, as happened to all Jewish business owners at the time? According to this record, the company had employed Wolf even before the French Republic came to an end. Then again, in the same letter, the company manager was quick to guarantee that his new employee would have no contact with the public, as required by the French government, due to his being an “israélite” (Jewish).

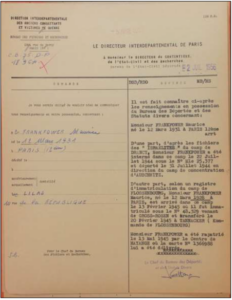

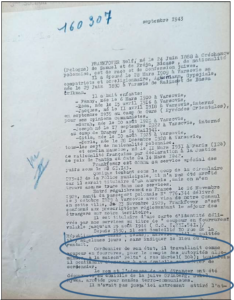

Despite being a foreigner and a Jew, Wolf Frankfower was “protected” because the German authorities needed skilled workers, as shown by the following record from 1943. He worked as a “fur cutter” in the “Pelta” factory in the 10th district of Paris, an held a work permit valid until August 25, 1944. We mention this date because it is very significant. We shall come back to this later.

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte.

As regards the children’s education, we were unable to find out any information about this.

Arrests and deportation

Between 1940 and 1944, despite being fairly well “protected’, the family came under threat from the French government’s anti-Semitic policies and due to their political activities. First of all, in September 1939, Jacques (Jacob) was arrested for his militant Communist activities, which were deemed dangerous. He was then interned in the Vernet camp in the Pyrenees from October 1939 through September 1942, prior to being deported on Convoy 37 to Auschwitz, where he died.

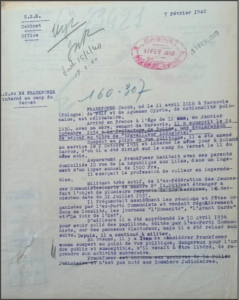

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

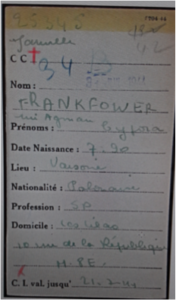

Joseph was the next to be arrested. On May 14, 1941, he was arrested during the “green ticket roundup”, which targeted foreign Jewish men. He was interned at Pithiviers, then transferred to Drancy camp, from where he was deported on Convoy 6 on July 17, 1942. He too died in Auschwitz.

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

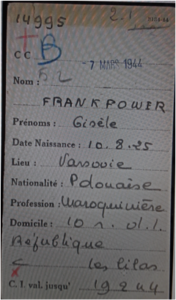

Next came Gitla (or Gisèle), an apprentice leatherworker, who was arrested and interned in Drancy on February 19, 1944 until March 7, when she was deported on convoy 69. She never returned home.

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

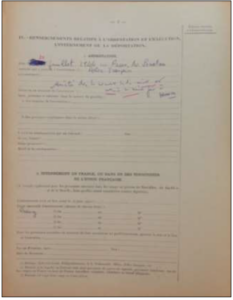

The Frankfower family was gradually decimated by the Vichy government’s anti-Semitic policies. Four more members of the family were arrested in July 1944, just as the Allies were liberating northern France following the Normandy landings. Wolf, Gypojiale (Cypora) and two of their children, Sarah and Maurice, the youngest child, were rounded up.

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

Wolf must have hoped that the work permit issued by the German authorities, which was due to expire on August 24, 1944, would help protect his family. However, despite holding the permit, Wolf, his wife and their daughter Sarah were arrested at their home in Les Lilas on July 21, 1944 and taken to Drancy. As for Maurice, he was not at home at the time. According to the testimony of his daughter, who we were able to track down, her father had not been living with his parents for some time due to the ongoing danger. The boy had been placed in the care of the UGIF (Union générale des Israélites de France or General Union of French Jews) and was staying at the residential vocational school on rue des Rosiers in Paris. The registration form completed when Maurice arrived at Drancy says that he was arrested during a round-up at the UGIF center on rue Secrétan. However, further research revealed that Maurice Frankfower was not on the list of children who were rounded up there. He must have been one of the other children arrested on the same day and taken to Drancy all together.

Source: Register from the ORT vocational school on rue des Rosiers, which was also a UGIF home.

On July 22, 1944, during one of the last major roundups organized by the SS officer Aloïs Brunner, commander of the Drancy camp, the French police arrested Maurice and took him, together with a number of other children from the UGIF homes in and around Paris, to Drancy, where he was reunited with his sister Sarah and his parents. We can only imagine the parents’ dismay at meeting up with their young son in such desperate circumstances. According to the Drancy registration records, the family members were all assigned to the same staircase and room number (3.4), but later then moved and split up. Sarah and Cypora appear to have stayed together in building 4.2, while Maurice and his father appear to have been separated and put in buildings 6.4 and 4.3 respectively. Ten days later, all four were deported on the last transport from Drancy, Convoy 77, which left for Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 31, 1944.

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

Life in the camp and the Liberation

The 1310 people, including 324 children, among them 13-year-old Maurice, left Drancy for the Bobigny train station on July 31, 1944. They were herded into cattle cars like animals, in which they spent three days and three nights on the journey to Auschwitz.

Carole Frankfower, Maurice’s daughter, with whom we were able to spend some time, shared with us some information that helped us to understand what happened to her grandparents, her aunt and her father. One of the other deportees, Joseph Gourand, known as Joe, helped and took care of her father. This young man no doubt played an important part in Maurice’s survival. Joseph and Maurice looked out for each other in the camp and struck up a friendship that was to last long after they returned to France, and which was passed on to Carole, like a legacy, when her father died. Joseph Gourand wrote his testimony in 1996 in a book entitled “Les Cendres Mêlées” (“mixed ashes”).

When they arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the family got out of the cars onto the platform, where the men and women were separated before the selection process took place. Sarah and Maurice, since they were young and fit, were selected to go into the camp to work. Maurice was only 13. He probably lied about his age or was big for his age, and thus avoided being condemned to death. Their parents did not survive, most likely murdered in the gas chambers shortly after they arrived. Wolf and Cypora had left their homeland in the hope of a better life in France, the country on which they had pinned so many hopes for themselves and their children and “the land of human rights” for so many of the migrants who had moved in France. They were sent back to their native Poland to die, simply because they were Jewish.

Sarah and Maurice were separated during their time in the death camps, but both survived. We have no way of knowing whether they had any contact with each other in that hellish place. Maurice, along with the other deportees, had to endure the forced labor, endless morning and evening roll calls, hunger, thirst, beatings, fear and cramped accommodation in the barracks. But he also had Jo to help him through such inhumane conditions.

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

In January 1945, the Russians bombed the camp. Many of the deportees, including Maurice, hoped that they would soon be liberated. Nevertheless, the following months were terrible, and it is difficult to comprehend how such a young lad found the strength to survive.

As the Russian troops were advancing, the Auschwitz camp was evacuated, and the SS made the deportees set off on foot in the cold on what became known as the death marches. Many of them died along the way, either because they could no longer walk, or because they were shot by the SS. The SS then decided what to do with the survivors, including Maurice. He was transferred to the Gross-Rosen camp, then to the Flössenburg camp, where he was booked in on February 13, 1945, before being taken to the Tannacker camp, a kommando work group that was part of Flössenburg.

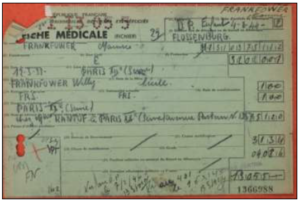

Maurice was eventually repatriated to Hayange, in eastern France, on May 13, 1945.

The return to France

Maurice had just turned 14 when he was repatriated to France. The health authority reported that he weighed just 83 lbs. (38 kg) when he arrived in May 1945. According to the medical form drawn up by the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees at the time, he was placed in the care of Madame Kantof, who lived in the 20th district of Paris. Thanks to Carole Frankfower, Maurice’s daughter, who has their marriage certificate, we discovered that Madame Kantof was in fact Maurice’s sister: Rosa Frankfower (also known as Rose). She had married Isaac Kantof on April 22, 1939.

Source: Carole Frankfower’s personal collection

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

Maurice went back to school, but he could no longer cope with the teachers’ strict discipline. Too many painful memories of the camps resurfaced whenever he was punished. He soon left school and went to work as a presser in a theater, where he had to use an iron that weighed over 15 lbs. It was hard work for a young man. Next came military service, during which he was unwilling to submit to army orders and was eventually discharged. His military service record states: “Irredeemable individual, can only just read and write“.

After this troubled period, Maurice began working as a sales representative for a company called Cartro, where he sold office supplies. He trained in this field, which enabled him and his wife to set up their own office supplies firm, SOMARCO, in 1962.

Our meeting with Carole

Our meeting with Carole happened as a result of some fortuitous research. In response to a message posted on Facebook rather like a message in a bottle, tossed into the sea, Carole replied: “The people you mention are my grandparents, my aunt and my father, Maurice. I’d be delighted to participate in any way I can in your wonderful project”. This was the start of a discussion in which we introduced the Convoy 77 project and our work as a class of 9th graders. Carole was deeply moved by the initiative, saying “my father would have been proud to be able to share this memory with the students”. Carole then agreed to assist us in our memorial project, and to share with us some valuable family records that she had. We were pleased to discover that, from the time he came back from the camps and right up to the end of his life, Maurice never ceased to make representations to the French government for recognition of not only his own rights, but also those of his family members who were murdered in Auschwitz.

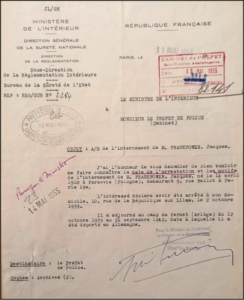

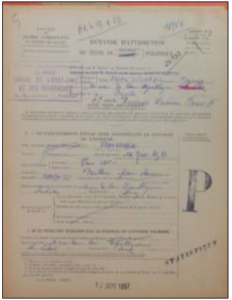

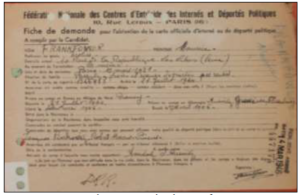

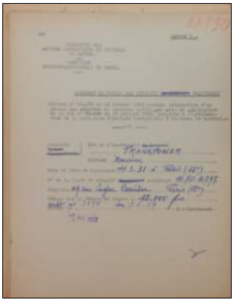

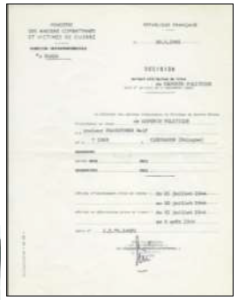

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

Source: French National Archives, Pierrefitte

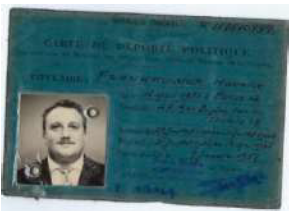

For both of his parents, his brother Joseph and his sister Gitla (known as Gisèle), he succeeded in having them recognized posthumously as having been “political deportees” (meaning that they were deported for political reasons). In 1957, the French government also recognized Maurice himself as having been a political deportee.

Records kindly sent to us by Carole Frankfower

During our meeting with Carole, she kindly entrusted us with a book published by the F.N.D.I.R.P (Fédération nationale des Déportés et Internés Résistants et Patriotes, or National Federation of Deported and Interned Resistance Fighters and Patriots) dating from 1957. This book, which was commissioned by Maurice, testifies to his desire to remember his loved ones who were persecuted and murdered on account of their religion, and to pass on their memory to those close to him. During his lifetime, Maurice continued to play an active part in the work of the Place des Vosges synagogue in Paris, and was involved in a number of Jewish groups, including the Colonie Scolaire, a non-profit organization founded in 1926, in which his daughter Carole is now also involved.

The National Federation of Deported and Interned Resistance Fighters and Patriots book about deportation, published in 1957

Maurice died in 1983 at the age of 52, when Carole was just 16 and her brother Marc was 24. Her father said very little to his daughter about what happened when he was deported. She was intrigued by the tattoo on his forearm, but was never able to get a clear explanation out of him. As for her older brother, his father didn’t talk much about the deportation to him either, but he often mentioned it in passing.

After her parents died, with Jo’s encouragement, Carole went on a memorial trip to Auschwitz.

Carole Frankfower and the 9th grade “Badinter” class from the Marais de Villiers middle school in Montreuil-sous-Bois during her visit to the school on February 7, 2023.

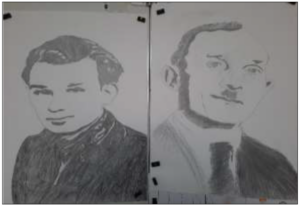

Portraits of Joseph and Wolf drawn by students from the 9th grade “Badinter” class

The portrait of Maurice drawn by Ilyes and Kylian, students from the 9th grade “Badinter” class

Français

Français Polski

Polski