Noussen GOURENZEIG

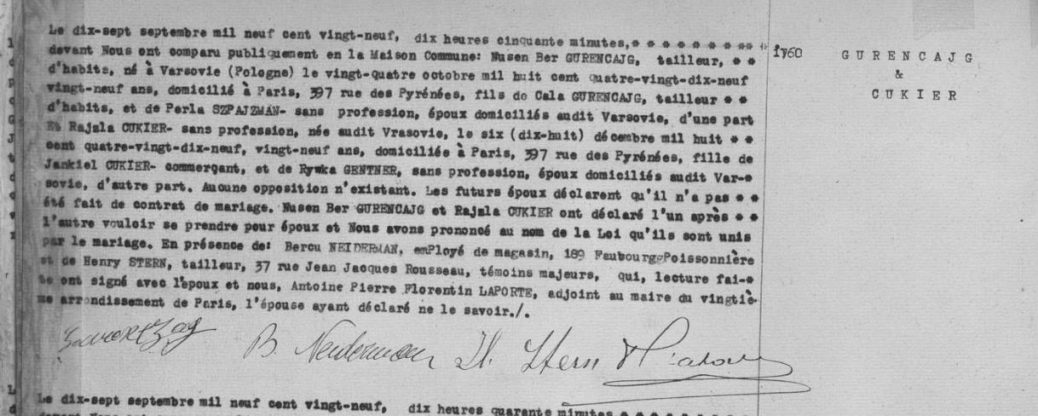

To the left, Noussen and Rosa’s marriage certificate. Source: Paris Archives, ref. 20M79

Depending on the source, Noussen’s first name differs: Noussen, Nuissen, Nusen or Noussem. His surname is also recorded in various ways: Gourenzeig, Gourenceig, Gourentzeig or Gurencajg. Throughout this biography, we refer to him as “Noussen Gourenzeig”.

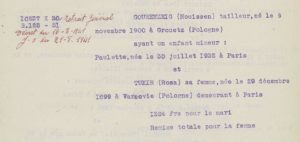

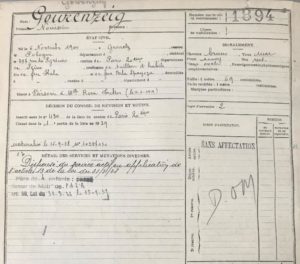

According to his marriage certificate, Noussen Gourenzeig, the son of Cale Gourenzeig, a tailor, and Perla Szpajzman, who did not work, was born on October 24, 1899 in Warsaw, a city which, at that time, was part of the Russian Empire. On the other hand, according to the official document that granted him French citizenship, he was born in Grouetz, a Polish city that was also part of the Russian Empire, on November 6, 1900.

Map of Europe in 1914.

Source: https://www.herodote.net/L_Europe_a_la_veille_de_la_Grande_Guerre-synthese-61.php

Extract from the decree dated September 15, 1938 granting Noussen French citizenship. Source: https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/mm/media/download/FRAN_0312_38517_Lmedium.jpg

According to the book written by his son after the war, Noussen fled Russia for Paris at the age of 18 in order to avoid being mobilized for the Russian-Polish war1. The war between Russia and Poland broke out in 1919 due to the lack of clarity in the Treaty of Versailles as regards the borders between the two countries. Russia wanted to take back some Polish territory, and vice versa.

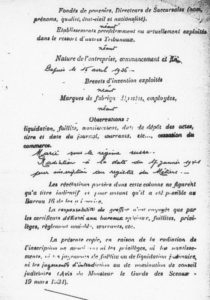

According to the minutes of the commercial court of the Seine department, Noussen was granted permission to reside in France in 1920.

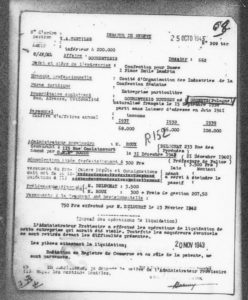

Extract from the minutes of the commercial court of the Seine department

Source: French National Archives, dossier reference 662

Subsequently, as confirmed by the marriage certificate at the top of this biography, Noussen married Rosa Tukier on September 17, 1929 in Paris, where the couple had four children: André, Joseph, Marie and Paulette. However, again according to the minutes of the commercial court of the Seine department, Noussen and Rosa had been married before they came to France, since the minutes say that they were “married under the Russian regime” And in fact, according to Noussen’s military service record, this marriage took place on June 4, 1919 in Warsaw. They may have had to get married again in France for administrative reasons.

Noussen’s military service record. Source: Paris Archives, ref. D4RI 3686

In his book, Joseph describes Noussen as “straightforward, steady and hard-working”2. His daughter Paulette also says that her father was a cheerful man who liked to laugh and joke. She adds that, in the evening, Noussen’s brothers would come to the apartment and they would all play together, at cards in particular.

As the 1931 census shows, they were living at 397, rue des Pyrénées in Paris. It was a truly cosmopolitan neighborhood. He worked as a dressmaker with two of his brothers and a seamstress at 1 place Emile Landrin, not far from the Place Gambetta, as evidenced by the 1941 trade directory.

From the Didot Trade Directory, 1941 edition. Source: Paris Archives

He also operated stalls at the Carreau du Temple, a historic covered market in the 3rd district of Paris. He worked long hours, from 6 in the morning to 10 at night. He was well assimilated into professional life and felt at home in France. He was granted French citizenship in 1938 by virtue of a decree issued by the President of the Republic, Albert Lebrun. At that time, people had to pay stamp duty in order to be granted French nationality, and Noussen paid 1324 francs. Becoming French was no doubt an important milestone for him.

His work enabled him to support his family. They lived a comfortable life and went on vacation to the seaside every year, where Noussen spent Sundays with them.

In 1940, the Vichy regime issued the first employment restrictions for Jews. All Jews were also required to report to their local police department. Noussen, however, refused to go.

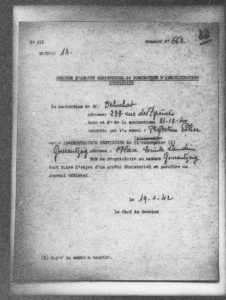

On December 21, 1940, at the request of the Police Headquarters, a Mr. Deluchat was appointed as the temporary manager of Noussen’s business.

Request for a ministerial order appointing a temporary manager. Source: French National Archives, dossier no. 662

On January 17, 1941, Noussen was struck off the Trade Register. He also lost his license to operate the Carreau du Temple market, where a lot of the traders were Jewish. Marc Knobel, in an article published in November 2018 in the journal Deux Mondes, explains: “On May 10, 1941, the collaborationist paper Le Matin reported: “Little by little, the Parisian business world is being rid of troublesome influences which, for too long now, have hindered its growth and its reputation for good taste and integrity. They will thus recover their authentic character […] In compliance with a German order of April 26, 1941, effective August 1, 1941, the Paris Police Headquarters withdrew the permits held by street traders, second-hand dealers and Jewish merchants. At the conclusion of two campaigns conducted in July and September 1941, 4,447 permits were withdrawn, summarizes historian Laurent Joly. 409 dealers at the Carreau market had their commercial license cards taken away. This operation was accompanied by a wave of temporary management orders. In May 1941, several thousand small Jewish businesses were hit.”

According to the article in the French newspaper Le Monde published online on December 5, 2015 “The law of July 22, 1940 provided for the systematic review of all naturalizations granted since 1927 – 1927, since the law of August 10, 1927, which replaced a very old one dating back to 1889, facilitated the acquisition of French nationality by reducing the residency requirement from ten to three years […] and by increasing the number of cases of automatic accession. Indeed, between 1917 and 1940, nearly 900,000 people acquired French nationality. […] For four years, the Commission excluded 15,154 people from the French citizenry, and lists were published in the French Official Gazette – a little fewer than half of them would have been Jews, although it is difficult to verify this. This was not a large number out of the 900,000 people who were liable to be stripped of their citizenship, because the Commission, even though the law did not mention it, was primarily aimed at the Jews. Since October 1940, Jewish foreigners had been interned in specialized camps or held in groups of foreigners, including those who had been “denaturalized”. The first deportation convoy (on March 27, 1942) changed the nature of this “denaturalization”; effectively, the wise men on the committee were now sending the Jews who had been stripped of their nationality to their deaths.”3

In 1941, as can be seen in the French Official Gazette dated August 21, 1941, the family lost its French nationality in accordance with the law of July 22, 1940. Noussen was very angry and felt that his family, now deprived of French citizenship, was in danger in the occupied zone. He therefore decided to move to the free zone. France was in fact separated into two zones: one in the north, which was occupied and run by the Germans, and the other in the south, which was run by Marshal Pétain’s government. According to a letter from the provisional manager of his business, Noussen must have left Paris in June, since it states “Mr. Gourentzeig would have discontinued his operations in June 1941, the date on which he left, leaving no forwarding address”.

Letter from the temporary manager of Noussen’s business. Source: French National Archives, Dossier no. 662

First of all, he tried to cross the demarcation line on his own, but was arrested and spent two weeks in prison in Chalon-sur-Saône. After being arrested the first time, he crossed the line for the second time with a people smuggler and found a place to stay in Lyon. Sometime later, his family came to join him. They lived at 11, place Antonin Gourju, on the quays of the Saône river, near the Place Bellecour.

The demarcation line at Chalon-sur-Saône, in the Saône-et-Loire department of France. Source: https://www.open-museeniepce.com/http:/photo6760

He then went to work for “La Petite Jeannette”, together with his son Joseph, and hired three people4. Everything was going pretty well: they were together, which was the most important thing. They even managed to buy some goods on the black market.

In 1944, the mood in Lyon became tense: the militia and the Gestapo were arresting a lot of Jews. Some members of the family were contemplating fleeing to Switzerland. Noussen, however, wanted to stay in Lyon, as he did not want to rebuild his life all over again; in Lyon he had a job, his routines and so on. The disagreement between the members of the family was a source of tension. According to his daughter, Paulette, Noussen did not realize the extent of the danger that he and his family were exposed to. On June 6, 1944, when the Normandy landings took place, he thought that the war would soon be over. He saw no point in hiding. The worst that could happen, he thought, was that his family could be arrested and imprisoned, but they would still be together. Noussen never imagined the horror of the killing centers. When Paulette’s teacher went to his home to try to persuade him to send her to stay in the countryside, she therefore found it very difficult to convince him. Ms. Constance Hofer had to go to 11 place Antonin Gourju several times before Noussen agreed. The tenacity of the teacher from the Lamartine school saved Paulette’s life.

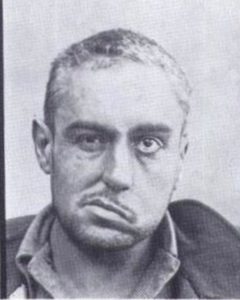

On July 18, 1944, it is said that a neighbor reported the Gourenzeig family to the authorities. French Gestapo agents therefore went to their apartment and asked them for their identity documents, to see if they were Jewish. According to Joseph’s account5, the arrests were made by a man known as “Gueule tordue” (Crooked mouth), a French militiaman and collaborator who was notorious for all the crimes and murders he committed around that time.

“Gueule tordue”, or “Crooked mouth”.

Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media494-Francis-AndrA

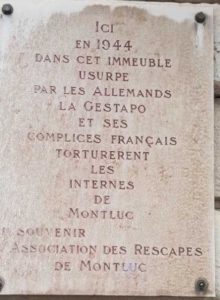

They were then taken to the Gestapo headquarters in Place Bellecour, where they spent the night. The Gestapo headquarters had in fact moved to Lyon after the Germans occupied the Free Zone. It was initially located on Avenue Berthelot, but after the city was bombed, it moved to the corner of Place Bellecour and Rue Saint Exupéry. This is where this commemorative plaque can be found today.

Plaque commemorating the victims of a Gestapo torture site in Lyon.

Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media.php?media=10131#fiche-tab

André managed to hide and avoid being arrested, as did Marie, who was able to escape.

A short while later, on July 19, Noussen, his wife and Joseph were transferred to the Montluc prison. There they were separated, Noussen and Joseph in one section and Rosa in another. Unfortunately, a few days later, André and Marie were also arrested and were taken to the same jail as the rest of the family.

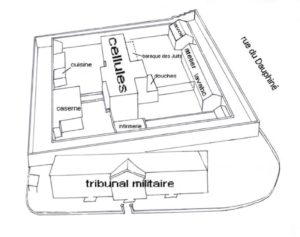

Montluc jail was at 4, rue Jeanne Hachette in the 3rd district of Lyon. It was built in 1921 on the slopes of Fort Montluc. Initially a military prison, it is best known for its role as a detention facility during the Second World War. Noussen was locked up in what was known as the “Jew’s barracks”, along with his sons. This was a building constructed out of wooden planks and canvas, about 30 yards long and 6 yards wide, where Jews were crammed in together in very harsh conditions.

The Jews’ barracks in the main exercise yard.

Source: Rhône departmental archives, ref. 4544 W 17

The location of the Jews’ barracks today. Source: Photo by Christèle Vial

Plan of the Montluc prison

Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media496-Plan-de-la-prison-de-Montluc-Lyon#fiche-tab

The section on the left was for the prisoners detained in cells, who were frequently shot. The section on the right was for people who were to be deported. The middle building was used to hold the Mischlingen, which means Aryan men or women who were married to Jews. During the day, they were free to go outside, except for the day before a deportation convoy, when a fence was erected to cordon off the building on the right. The camp gates were guarded by French police. During the Gourenzegs’ internment in the camp, on July 28, 1944 to be precise, the courtyard was fenced off to separate the Jews from the other prisoners. When they arrived in Drancy, on July 22, 1944, Noussen, Joseph and André were interrogated6. Then on July 31 1944, 17 before the camp was liberated, Noussen left Drancy together with his family. They were taken to La Courneuve, then to Aubervilliers and finally to Paris. When they got there, they were picked up by the SS and then crammed into cattle cars together with the other people who were deported on Convoy No. 77, as described in the Shoah Memorial records.

Jews interned in Drancy camp, France, between 1941 and 1944

Photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Source: http://www.ajpn.org/images-camps/1287327403_juifs.jpg

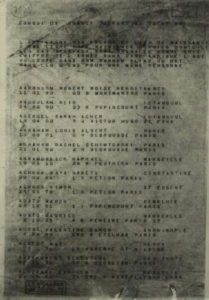

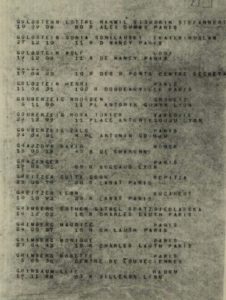

Extract from the list of people deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 77.

Source: Copy of 1.1.9.9 / 11191135, in conformity with ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives.

Alphabetical lists of Jews deported from Drancy transit camp (Original transport lists held by the French National Research Agency)

In the cattle car, the deportees were counted and recounted time and time again. There was just one tin bucket for their needs. The journey lasted three days and two nights, and there was nothing to eat or drink. The travelling conditions in the car were very harsh: the deportees suffered from hunger, thirst and disease. Many people lost their lives during the journey. The bodies were just left lying where they fell. Anyone who managed to escape was shot on the spot, in front of the other prisoners.

When they arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the SS carried out a selection. The men were sent to one side and the women to the other. Noussen was separated from his wife Rosa and his daughter Marie, who stayed behind in Birkenau, but remained together with his sons, André and Joseph. All three of them were then taken to the Auschwitz camp.

Joseph, André and Noussen were shorn and shaved, vaccinated and given a striped uniform. Joseph and Noussen were assigned to the first floor of Block 2A, while André was put on the floor above. They worked all day in a stone quarry and had only a 30-minute break..

During the winter of 1944, the weather was terrible, it was very cold indeed and the prisoners were inadequately dressed for the weather. André could no longer stand living in such conditions and confided in his father:7

“- I can’t take it anymore. I can’t even eat anymore.

– Hold on, I’ll help you.

– Help me with what, Dad? A few days more or less, what does it matter?

– It’s going to be all right.

– I can’t live like this anymore, Dad.”

The day after this conversation, Andre threw himself out the window, and then Noussen said:

“You can murder us all. You can do what you want with me but you can never kill the pain of a father whose feet are covered with his son’s blood. He is dead, you can’t do anything more to him.”

This experience caused him overwhelming emotional distress: he was never the same again after Andre died.

A short time later, their quarantine came to an end and they were allowed to move around the camp after work until the curfew. Noussen had little hope that his wife had survived, but he found it hard to believe that she may have been killed in the gas chambers. He had no news about what had happened to Marie. He did however learn that his three brothers, their wives and children had all been gassed, except for Izaï, who had been shot dead with a revolver.8

After receiving such tragic news, Noussen’s only objective was to keep Joseph alive. He sacrificed himself to ensure his son’s survival, even going so far as to give him his portion of food and to take his place in the stone quarry. Some time later, in November 1944, a selection was made and because Noussen had given all his food to Joseph, he was no longer strong enough to work: he was therefore selected to go to the gas chambers.9

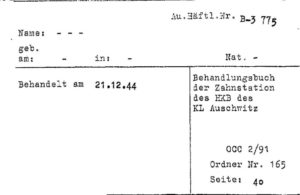

The sequence of events is unclear, however, because in his book, Joseph mentions having some dental work done and explains that his father went with him to the dentist’s office.

Auschwitz infirmary record. Source: Bad Arolsen International Tracing Services collection.

The Auschwitz reports state that Joseph went to the dentist in December 1944. In any event, it was in late 1944 that Noussen was taken away to be killed. He must have been relatively calm because he felt that his son Joseph would be strong enough to carry on without him, and he made Joseph make a promise: “This promise that I made to my father and from which no one could ever part me: to keep and to take care of my sister and to make our family tree grow back from one single root.”10

All that remains of Noussen today are the memories passed on by his children, a few salvaged photos and a name engraved on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, alongside those of 75,567 other Jews who were deported from France.

A section of the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris. Source: Photo by Christèle Vial

Camille, Célestin, Corentin, Floriane and Katie

Notes

- GOURAND Joseph, Les cendres mêlées, Le Cherche-Midi, Collection Documents, 1996, p.16

- Ibid p.16

- https://www.lemonde.fr/justice/article/2015/12/05/decheance-de-nationalite-le-precedent-de-vichy_5995601_1653604.html

- GOURAND Joseph, op. cit., p 45-46

- Ibid p.63

- Ibid p.68

- Ibid p.80-81

- Ibid p.82

- Ibid p.102-103

- Ibid p.103

Français

Français Polski

Polski