Joseph GOURENZEIG

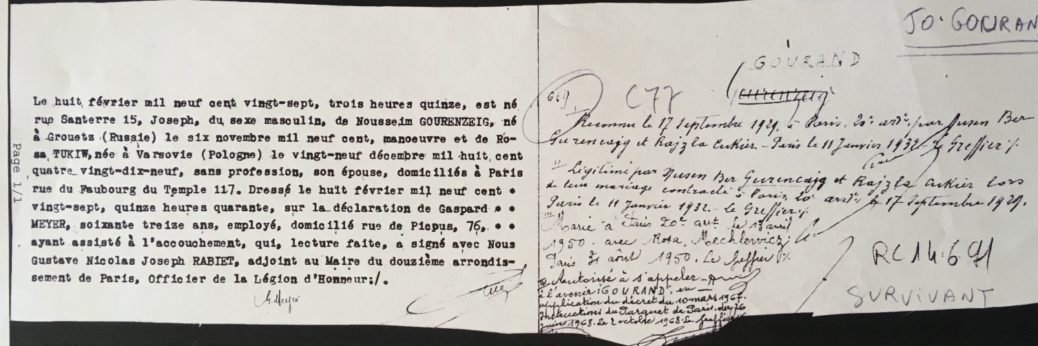

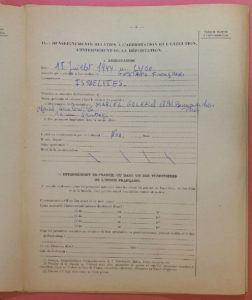

To the left, Joseph Gourenzeig’s birth certificate. Source: Shoah Memorial Archives

Joseph Gourencajg, also known as Gourenzeig, was born on February 8, 1927 in the 12th district of Paris, France. He was the son of two Polish immigrants, Noussen and Rosa and was the third of four siblings. According to the 1931 census, the family lived at 397, rue des Pyrénées. Joseph went to the local school at 104, rue de Belleville.

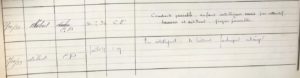

On the school’s registration form, the state education officer noted that Joseph was “not very intelligent”. The future would reveal, on the contrary, that Joseph was very intelligent, but he was not interested in school, which is why his father later enrolled him in a tailoring school.

Extract from the 1931 census. Source: Paris Archives

Extract from the register of the school on rue de Belleville. Source: Paris Archives, ref. 2846W 7

During the 1940s, after the outbreak of the war, his father sent him and the rest of his family to live with an old English woman in a small village near Sens, to keep them safe. They returned to Paris a few days later, however.

In 1941, Joseph, along with all of his family members, lost his French nationality under the terms of the French decree dated July 22, 1940. According to an article in the French newspaper Le Monde: “The law of 1940 […] officially concerned “the revision of naturalizations” but its first section referred to “the revision of all acquisitions of French nationality“. This is quite different, since naturalization and the acquisition of nationality are not at all the same thing. Firstly, in terms of numbers, there are twice as many people who acquire French nationality as those who are naturalized. Secondly, legally, the children of naturalized French parents are born French, whereas naturalized persons are born foreigners”.

After they lost their French citizenship, Joseph’s father decided to look for a place to relocate his family in the free zone14. He found a place to live in Lyon and sent a “people smuggler”, or trafficker, to Paris to bring his family to join him. Joseph’s sisters were the first to arrive at the Gare de Lyon station in Paris, where Joseph, his brother and his mother were to meet them. However, the family could not find each other. His mother therefore got off the train in Dijon in order to go back to Paris to find her daughters, while Joseph and his brother André continued their journey with the trafficker.

The train stopped just before Chalon-sur-Saône, but when they tried to cross the demarcation line into the free zone, they were captured and the trafficker was killed. In the jail in Chalon, they were interrogated one by one by a German officer. The conditions in the prison were poor: they had a sort of vegetable soup to eat, meat that smelled rotten and a bit of dry bread. After the meal, they were allowed to go out for half an hour in an enclosed yard. At night, the smell of the toilets was appalling. A trial was held and Joseph and his brother André were sentenced to eight weeks in prison.

One night, around 5 a.m., a soldier unlocked all the cells in the prison: he had a list of names. He called several prisoners, including Joseph and his brother: they were then taken to another prison, in Autun, in trucks. Compared to the prison of Chalon sur Saône, this prison was somewhat more comfortable but the conditions were similar. After serving their eight-week sentence, Joseph and Zalo were taken to the prefecture. The person who questioned them, realizing that the two brothers were French, entrusted them to two police officers who were to drive them to the train station to return to Paris.

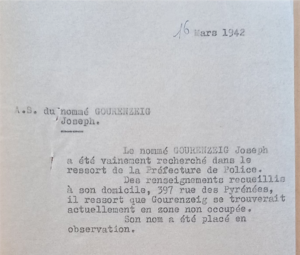

When they arrived back in Paris, they returned home to their mother and sisters, but they were now were regarded as escaped prisoners. The first night, their mother, who was afraid that the police would show up, hid Joseph and Zalo in Zalo’s maid’s room. The next day, at 5 a.m., the police questioned their mother, asking where her sons were. The police abandoned the search for the time being. However, records show that they returned to the Gourenzeig’s house later on, still hunting for Joseph and his brother.

Internal memo from the Department of Foreigners and Jewish Affairs. Source: Paris Archives, ref. 77W213-130216

With the help of an aunt, they found a smuggler who got them out of Paris and across the demarcation line. They set off by train and then embarked on an exhausting trudge through the snow. The very next day, they reached the free zone. The family came to a hamlet. They knocked on some doors and a peasant woman let them in. She sat them down in front of the fire and gave them something to eat. A few hours later, the peasant woman called the police to ask them to take them in for questioning. The police called their father and sent them to Lyon. When they arrived, they met up with Noussen in their new apartment at 11 place Antonin Gourju.

The days went by in Lyon and life was good. Joseph worked as a tailor, with his father, and made lots of new friends.

On July 18, 1944, the Gestapo arrested him at his home on the grounds that he was Jewish. An unknown person had reported him.

Extract from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War file. Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

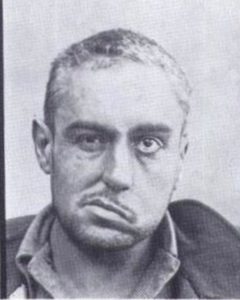

When the Gestapo went to his house to arrest him, they looked at his identity papers. There was no mention of “Jew”, so he and his parents were arrested. HIs sister, Marie, managed to escape and his brother, Zalo, hid in a closet. Joseph and his parents were taken to the Gestapo headquarters on Place Bellecour in Lyon for a background check. According to Joseph, he was interrogated by a man known as “Gueule tordue” (“Crooked mouth”), whose real name was Francis André.

“Gueule tordue”, or “Crooked mouth”. Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media494-Francis-AndrA

Francis André had joined the Gestapo in the spring of 1944. He eventually had 60 people working under him, divided into three groups, who took turns arresting Jews and resistance fighters. André arrested and interrogated Jews and resistance fighters, then handed them over to the Gestapo’s anti-Jewish section, but kept all their valuables.

After that, from July 18, 1944 to July 30, 1944, Joseph was interned in the Montluc prison, which was at 4 rue Jeanne Hachette in Lyon.

The Jews’ barracks in the main exercise yard

Source: Rhône departmental archives, ref. 4544 W 17

The location of the Jews’ barracks today. Source: Photo by Christèle Vial

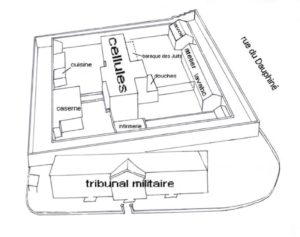

Plan of the Montluc prison

Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media496-Plan-de-la-prison-de-Montluc-Lyon#fiche-tab

It was built in 1921. Initially, it was a military prison, but became a German prison from January 1943 until August 24, 1944. The living conditions were terrible: the cells were about 20 by 20 feet and held 8 to 10 people. The beds were replaced by bags of straw. Each cell had only one bucket that served as a WC and one bowl for washing. For meals, there was only black bread. Prisoners were allowed to go out for just 45 minutes a day. Diseases such as typhus spread rapidly, as did lice, fleas and rats. The prison included the so-called ” Jews’ barracks”, a building of about 100 feet long by 20 feet wide, in the courtyard. The Jews were crammed into this building with no access to washing facilities. This is where Joseph and his father, and later Zalo, were imprisoned.

Joseph and his family were transferred by train to Drancy camp, north of Paris, on July 22, 1944.

Information sheet from the Lyon Regional Judicial Police Department. Source: Rhône Departmental and metropolitan archives, ref. 3335W26, 3335W19

Drancy camp was made up of 3 distinct sites, 3 blocks of buildings in the shape of a “U”.

Jews interned in Drancy camp, France, between 1941 and 1944

Photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Source: http://www.ajpn.org/images-camps/1287327403_juifs.jpg

The section on the left was for the prisoners detained in cells, who were frequently shot. The section on the right was for people who were to be deported. The middle building was used to hold the Mischlingen, which means Aryan men or women who were married to Jews. During the day, they were free to go outside, except for the day before a deportation convoy, when a fence was erected to cordon off the building on the right. The camp gates were guarded by French police. During the Gourenzegs’ internment in the camp, on July 28, 1944 to be precise, the courtyard was fenced off to separate the Jews from the other prisoners. Between 1941 and 1944, numerous deportation convoys departed from Drancy. Joseph was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, 17 days before the camp was liberated, together with his parents, brother and sister. Auschwitz was a concentration camp in Poland, and also a killing center. They travelled on a cattle train in which there was only one bucket that served as a water closet for the whole car. They had nothing to eat or drink during the journey, which lasted three days and two nights. The deportees spread various rumors about where they were headed.

When they arrived, on the night of August 3, 1944, the SS made a selection. Joseph’s mother and sister stayed in Birkenau, while Joseph, his father and his brother went to Auschwitz. Joseph, André and Noussen were shaved, vaccinated and dressed in striped uniforms. Joseph was assigned the number B3775, by which he was known throughout his time in the camps. Joseph and Noussen were put on the ground floor of block 2A, while André was put on the upper floor. When they arrived at the camp, they were kept in quarantine and worked in a stone quarry.

During the winter of 1944, the weather was awful; it was extremely cold and the prisoners were not dressed for the weather. Joseph’s brother Zalo did not want to suffer anymore, and decided that he would rather die11. After that, Noussen did everything he could to make sure that his son Joseph would survive. Thanks to his father, Joseph found work in the laundry. In December 1944, he went to the camp dentist several times, and later wrote that the dentist was more like a plumber!41 Something that is unclear in the sequence of events is that Joseph said that his father was there with him when he saw the dentist. However, in his book, he also wrote that his father was selected to go to the gas chambers in November. Either way, at the end of 1944, Joseph found himself alone in Auschwitz, without his brother or his father, both of whom were dead by then.

At the beginning of 1945, after the Russians began bombing the camp, Joseph, like thousands of others, was evacuated from Auschwitz. He took part in what historians later called “the death marches”. The first stop was at the Gleiwitz camp, a sub-camp of Auschwitz. They then passed through several Polish villages and were then put on a train to Czechoslovakia and subsequently to Germany42.

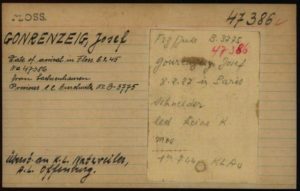

Joseph and the few other survivors were admitted to the Flossenburg camp on February 6, 1945. He was registered under the number 47386 and was assigned to the Ukrainian block. In his book, Joseph is critical of the behavior of the Ukrainian prisoners towards the Jews43. During the day, he and the other prisoners were sent out of the camp to break stones. One day, after a selection, Joseph was sent to another, cleaner block, where he stayed for about three weeks. During this time, he was better fed and excused from work.

Flossenburg. Source: Arolsen Archives International Center on Nazi Persecution

After that, on March 22, 1945, Joseph was moved from the camp and transferred by train to Natzweiler/Offenburg, which was near to the front line. There, the prisoners were responsible for filling in the holes made by bombs and repairing the railroad tracks. The front line was moving forward.

Extract from the Natzwiller camp archives. Source: Arolsen Archives International Center on Nazi Persecution

Joseph was once again put on a train and, despite being bombed by the Nazi air force, made it to another camp for a stopover, and then the convoy set off again. Joseph wrote about the SS commanders who continued to “wander around their ruined Reich”44, not knowing where to take their prisoners next. At some point, they got off the train and walked deep into the woods, where finally, one morning, Joseph and his companions woke up alone: the SS had fled during the night. Joseph then walked to the little town of Immendingen where he came across the French army. The commander kept Joseph with him as an interpreter.

Joseph then returned to France. He was repatriated to Paris, where he was taken to the Lutetia Hotel. Joseph then began another struggle: to keep the promise he had made to his father: “This promise that I had made to my father and from which no one could ever unbind me: to keep and to take care of my sister and to ensure that from a single root the tree of our family would grow again”.

Français

Français Polski

Polski