Riven KIRSCHBAUM

(Berlin 07.10.1922 – Paris 01.02.1984)

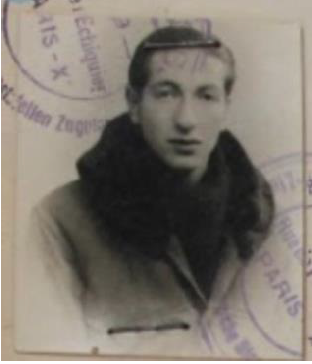

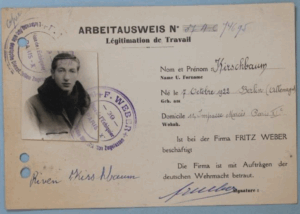

Photo of Riven Kirschbaum © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier 21 P 580.176.

The biography you are about to read was written by the 9th grade students from class 3eA at the Franco-German junior high and high school in Buc, in the Yvelines department of France, under the guidance of their German teachers, Lisa Rech and Marianne Hoock-Douilly, and their history teacher, Hélène Guerder. The school is jointly administered by the French and German governments, and focuses on biculturalism and French-German relations. The biography is therefore available in both French and German, in keeping with the school’s ethos, and has since been translated into English.

We investigated the lives of three deported people, Flora and Mirthil Cahen, and Riven Kirschbaum. Our research took us from Paris, where all three lived, to Berlin, where Riven Kirschbaum was born. We felt it was important to learn more about their lives in these places before, during and, in Riven Kirschbaum’s case, after the Second World War.

Although this biography focuses only on Riven Kirschbaum, we would be delighted if you would read Flora and Mirthil Cahen’s biography as well.

Thanks for reading!

I. Riven’s childhood

Riven’s mother, Esther (or Estera), was born in 1895[1]. We do not know when his father, Chaïm Kirschbaum, was born. Esther and Chaïm were married in June 1914 in Lódź[2], a large textile manufacturing city that was part of Russia at the time and was dubbed “the Manchester of the Russian Empire”. Prior to the First World War, Jews accounted for over 30% of the city’s population.

We can safely assume that Chaïm was drafted into the Russian army during the war, given the significant interval between the couple’s wedding and the birth of their first child, a daughter. In fact, Riven’s sister, Annie[3](or Anna) was born on March 10 1918 in Koło[4], a city in the central part of Poland, which regained its independence, after a 123-year hiatus, following the end of the First World War, on November 11, 1918.

When Poland became independent, the outlook changed for minority groups, especially Jews, who were obliged to integrate into Polish society (in particular, their children were required to go to Polish state schools).

This may well have been the reason that the family decided to emigrate to Germany.

During the Second World War, Germany annexed the area around Koło. In 1939, more than a third of the people living in the town were Jewish[5].

The family, or at least Esther, must have left Poland sometime between the end of the First World War and 1922. Riven[6] Kirschbaum was born on October 7, 1922 in Berlin, in Germany. He lived on Grenadierstraße until 1929[7].

Residence certificate dated August 16, 1923 © Kirschbaum family archives

The above record states that Riven lived with his mother. His father is not mentioned at all. Did he stay behind in Poland? Had he already left for France? Anna (or Annie) probably also lived with their mother, who is listed in the 1928 Berlin telephone directory as a Handelsfrau (shopkeeper or saleswoman)[8].

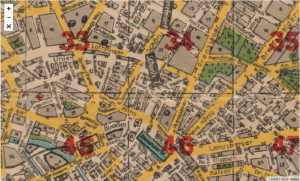

Grenadierstraße was in the “Scheunenviertel”, or “barn district” in the center of Berlin, not far from Alexanderplatz (see map below). It was a poor, predominantly Jewish neighborhood that was home to many Eastern European Jews, including Esther Kirschbaum. Horst Helas, who wrote a book about it in 2010, described it as an “open ghetto”[9].

Plan of Berlin, 1926,

www.berliner-stadtplansammlung.de

Men talking on Grenadierstraße, Walter Girke, 1928,

in: Das Scheunenviertel, Spuren eines verlorenen Berlins, Hause & Spender, p.119.

In the 1920s, it was a bustling street with many stores, businesses and religious buildings.

N°.31 Grenadierstraße, close to where Riven lived – Abraham Pisarek, 1930,

in: Das Scheunenviertel, Spuren eines verlorenen Berlins, Hause & Spender, p.114.

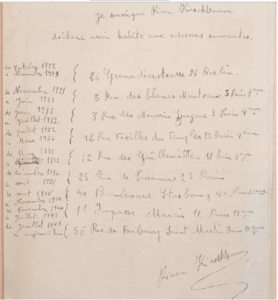

In 1929, Riven Kirschbaum, along with his mother and sister, emigrated to Paris[10]. His application for naturalization as a French citizen[11], made in 1947, lists all his addresses in Paris between 1929 and when he was deported.

It is clear from this list that Riven’s family decide to settle permanently in the city. They moved home several times, but always stayed within a fairly small area of the Marais district, possibly so that the children would not have to change schools. They subsequently moved a short distance away, but again to a neighborhood with a high concentration of Eastern European Jewish laborers and craftsmen.

Riven Kirschbaum © French National Archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p.18.

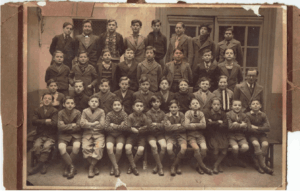

Soon after he arrived in France, seven-year-old Riven started school and began to learn French. We were not able to find out which school he went to, but it was probably the one on rue des Hospitalières Saint-Gervais.

In this school photo, Riven is 2nd from the right in the 2nd row, beside the teacher © Kirschbaum family archives.

We know very little about Riven’s childhood or adolescence prior to 1943, other than that he was already working as a furrier before the war.

The German Occupation

In a letter dated 1959, Riven explained that during the Occupation, after his father was deported[12], he had to care for his mother, who was paralyzed. He worked as a fur cutter at 39 rue de l’Échiquier[13], in the 10th district of Paris, an area well-known before the war for its Ashkenazi furriers[14]. He then fled to Lyon, in the Rhône department of France, where he shared a hotel room with a former workmate, Max Endel. Riven then joined the Resistance, and got involved in “posting clandestine newsletters in mail boxes”[15], in other words he distributed illegal Resistance publications. By January 1943, however, he was back in Paris, possibly only temporarily.

II. DEPORTED FOR THE FIRST TIME

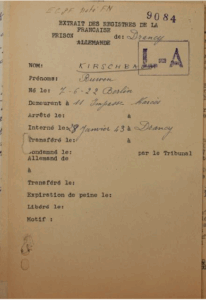

Riven was arrested for the first time on January 26, 1943. At the time, he was staying at 11, impasse Marcès, in a working-class area of the 11th district of Paris. He was interned in Drancy camp, in the north of the city, on January 28, under the name of Ruven Kirschbaum. We do not know how or why he was arrested (during a roundup, a routine ID check, for not wearing the yellow star, etc.).

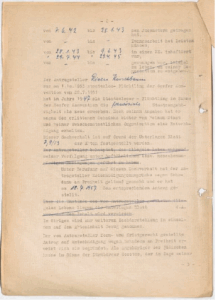

File on Riven Kirschbaum © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P 580 176

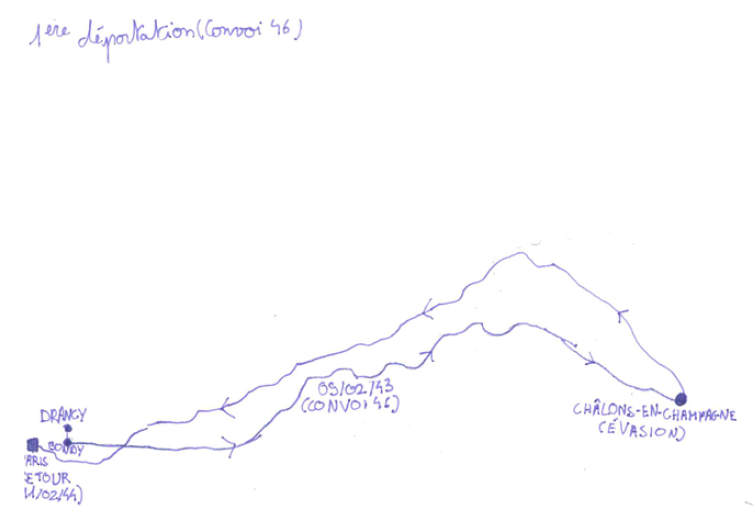

On February 9, 1943, he was loaded into one of the cattle cars that made up Convoy 46, which left Le Bourget station bound for Auschwitz, and was described in a police report as, “a convoy made up of 1,000 Jews of both sexes, mostly women and children”[16]. At 4 p.m., when the train stopped at Châlons-sur-Marne (now Châlons-en-Champagne) station, eleven deportees tried to escape by jumping from the moving train. The SS officers who were guarding the train set off in pursuit. The French police fired at the deportees just outside the station, but the area was packed with civilians. Seven men and one woman were caught in the ensuing chase, but three men, including Riven Kirschbaum, managed to disappear into thin air. A little later on, another deportee tried his luck. He too jumped off the moving train but ended up surrendering when he was shot at[17].

According to an SS officer’s report to his superiors, “the French government workers did their utmost to catch the fugitives”. He went on to say that around 8 p.m., two “Jews who had escaped from the convoy were arrested by the French military police in Châlons-sur-Marne” and “Only one Jew is still at large”. It was Riven ! There were very few escape attempts such as this, which were incredibly risky, and Riven was one of the few deportees to pull it off[18].

Map of Riven Kirschbaum’s 1st deportation, by Haoyu Guo (of class 3eA)

III. AFTER THE FIRST DEPORTATION

Riven escaped from Convoy 46 on February 9, 1943, arrived back in Paris on February 11[19], and then “disappeared” until June 24, 1944, when he was arrested again, most likely at a checkpoint, for being found in possession of a false identity card. The card was in the name of Joseph Pierre Hubert Encausse, who was born on November 2, 1926 in Aureilhan, in the Hautes-Pyrénées department, and lived at 12, rue du Laurier in Chambéry, in the Savoie department. Riven Kirschbaum’s photo and fingerprints were on the card[20]. A very good forgery indeed!

When he was interrogated, Riven admitted that he was also in possession of a forged work certificate, which he said he had bought for 150 francs at the Tout va bien café, and a bogus food ration card. He also claimed to have spent time in Chambéry[21] The chargesheet reads: “In addition, despite being of Jewish race and Polish nationality, as Kirschbaum travelled by train from Paris to Chambéry and back without requesting prior authorization from the relevant authorities, and as he has no identity document bearing the word JEW, [we] are charging him with illegal travel and failure to carry an identity document bearing the word JEW, offences covered by and punishable under the laws of November 9 and December 9, 1942, articles 1 and 2”[22].

On July 7, 1944, the 17th Chamber of the Seine Criminal Court sentenced Riven to one year in the La Santé prison in Paris for using a forged identity card[23]. On July 27, 1944, the Police Commissioner wrote to “the Divisional Commissioner, Deputy Director for Jewish Affairs”: “I am hereby making available to you, for any purpose, Ruben Kirschbaum, born October 7, 1922 in Berlin, of undetermined nationality, of Jewish race (underlined in the original text), single, furrier, of no fixed abode”[24]. In Riven’s case, “being made available” meant being interned in Drancy on July 29, 1944[25]. This time, he was assigned the serial number 26,082. After the war, Riven declared that he had been involved in an uprising at the La Santé prison on July 14, 1944[26].

IV. DEPORTED FOR THE SECOND TIME

On July 31, 1944, Riven Kirschbaum was deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp on Convoy 77, the last major transport of Jews from Drancy[27]. Although Riven had previously been deported in February, when it was very cold, the heat in July 1944 was surely just as horrific. 1,306 people of all ages, including some 300 children, were deported “to an unknown destination”, just as the Allies were nearing Paris. Crammed into cattle cars, with straw on the floor, little or no water, no sanitation and no fresh air, the deportees had to endure a journey that lasted more than three days. At least two groups attempted to escape en route. One group was caught, and the 60 men in the car were shackled naked and locked in with no food or water. The men who were travelling in a car with Jérôme Skorka also tried to break free, using “tools” supplied by the Drancy camp resistance group, but they were lucky enough not to be found out[28].

When Riven arrived in Auschwitz during the night of August 3-4, he was among the 291 men and 183 women that the Nazi doctors selected to enter the camp to work. The other prisoners, including anyone over the age of 45 (with a few exceptions), sick people and children, were sent straight to the gas chambers. Their bodies were then burned in the nearby crematoria.

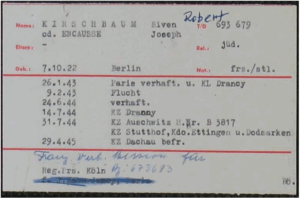

Two days after he arrived, at the age of 21, Riven had the serial number B-3817 tattooed on his arm[29]. From that moment on, the number became his identity. He had to learn it off by heart in German, which luckily he could already speak. Thus began his journey through the concentration camps, where survival was a constant challenge. Unfortunately, we have no details about what type of work Riven did during the three long months he spent in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

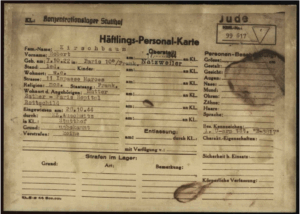

Having survived the routine selections, during which men were often sent to their deaths in the gas chambers, Riven/Robert was transferred to the Stutthof camp on October 28, 1944. There he was assigned a new serial number: 99,617.

Kirschbaum, Riven_TD 693 679 104292058, Arolsen Archives. The date on which Riven was interned in Drancy is incorrect: this happened quite often.

Kirschbaum, Riven_Häftlings-Personal-Karte_Stutthof_4519841 © Arolsen Archives.

The Stutthof concentration camp was in Poland (some 22 miles east of Gdansk[30]), in an area that the Third Reich had annexed in September 1939. It was first used to intern 150 Polish prisoners of war[31]. Around 120,000 people were deported to Stutthof, some 85,000 of whom died[32] as a result of the appalling conditions there (forced labor, typhus epidemics, summary executions, etc.). Initially, the Stutthof concentration camp was built to persecute and exterminate Polish prisoners, but its role subsequently expanded to include the mass extermination of European Jews[33].

In October 1944, the Hailfingen concentration camp, one of the Dachau satellite camps, asked for 601 Jewish deportees to be transferred there due to a labor shortage[34]. Riven was one of the prisoners chosen to go, the majority of whom (540)[35], like him, had originally come from Auschwitz. He arrived in Hailfingen on January 17, 1945 and was once again assigned a new serial number: 40,678[36]. He was listed as a Polish Jew, even though his record states that he was born in Paris.

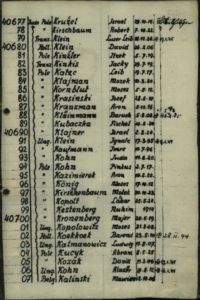

Kirschbaum, Riven_TD_693_679_104292058 © Arolsen Archives, Hailfingen register

During his time in Hailfingen, Riven’s work involved extending the airport. It was exhausting and degrading work, carried out in appalling conditions[37]. When the camp closed in mid-February 1945, the remaining deportees were all transferred to other camps. Riven and 295 other men were sent to Dautmergen, which was annexed to the Natzweiler-Struthof camp[38]. The next mention of his name is on a list of 973 prisoners no longer fit to work, who were transferred from Dautmergen to Dachau on April 7, 1945. This time, Riven was described as a “French Jew”, the only one on the list.

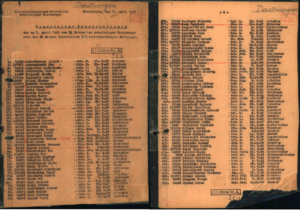

Namentliche Transportliste, I.T.S. digital archives, photo N°72Na,

© Arolsen Archives

While many of his fellow prisoners fell victim to the death marches, Riven was sent to Allach, the largest of the Dachau annex camps, where prisoners were sent to work for BMW. The exact date on which he arrived in Dachau[39], is not known, but was probably between April 7 and 13, 1945[40]. He appears to have been listed there as Robert – or Joseph – Encausse (with his correct pre-war address in Paris) in May 1945[41].

Riven was eventually liberated from Allach by the American army on April 29,1945[42]. He was repatriated to the Mulhouse reception center in France on July 20, 1945, under the surname Encausse. A fellow deportee, Maurice Bakcha, testified to this on August 29, 1945.

Map of Riven Kirschbaum’s 2nd deportation route, by Haoyu Guo (of class 3eA). It does not show the Dautmergen camp in Baden-Württemberg, some 25 miles south of Hailfingen, which Riven passed through in April 1945.

V. AFTER THE WAR

When Riven returned from the camps, he was 22 years old, weighed just 49 pounds and was suffering from typhus[43]. He had a broken nose and his back was covered with scars caused by being beaten with whips[44]. Riven, who survived two deportations and two typhus infections, suffered throughout his life from various conditions, which were all listed on January 14, 1960 by a Dr. Grimberg (who certified that he was 70% incapable of working)[45].

Riven rented an apartment at 55 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin[46], and then moved to 12 rue Bouchardon, in the 10th district of Paris. His mother, who was not deported, died at the age of 62 on April 9, 1959, at the Rothschild Hospital in Paris[47].

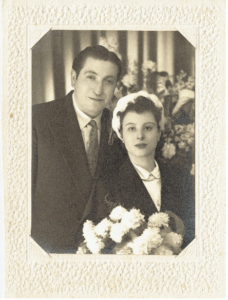

He returned to work as a furrier, and it was in the fur workshop that he met his future wife, Fernande Barbier, who was originally from the Franche-Comté region of France[48]. They were married on April 26, 1952 in the town hall in the16th district of Paris[49].

Riven Kirschbaum and Fernande Barbier © Kirschbaum family archives

In later years, Riven ran a bar, then a dry-cleaning service on rue Rodier (where the well-known singer Dalida was one of his clients), then another bar, this time on rue de Moscou. He was determined to be his own boss. His cockiness and charisma helped him to outshine the competition. He spoke perfect French and regularly used Parisian slang[50].

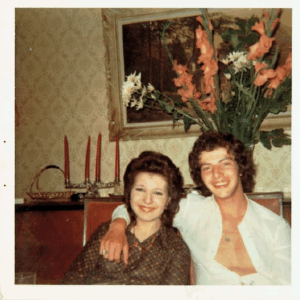

Fernande and Riven, now known as Roger, had two children: Patrick, who was born on June 27, 1953, and Catherine, born on 29, 1954[51].

Catherine and Patrick Kirschbaum © Kirschbaum family archives

His son Patrick remembers him as a jovial, easy-going man who was well-liked by all and made friends easily. After what happened to him during the Second World War, Riven was firmly committed to freedom, and always remained obsessed with not wasting food. Patrick describes his father as an atheist. Riven was a fan of Line Renaud and enjoyed listening to negro spirituals. He spoke both German and Yiddish, but never spoke either in front of his children. He had no particular political allegiance, but gave two pieces of advice to his children: never vote for the extreme right, and never give money to the Red Cross. This was because, in his opinion, the Red Cross did not live up to its humanitarian promises during the war.

Fernande and Riven/Roger separated in 1973 and were divorced on June 18, 1974. On December 13, 1974, he got married again, this time to Edith Blanchard, who was born in the 18th district of Paris on March 14, 1934[52].

Riven died at the Lariboisière hospital in Paris on February 1, 1984. He was 61 years old. He was cremated at Père Lachaise and his ashes are buried in the Saint-Ouen cemetery in Paris[53].

VI. POST-WAR ADMINISTRATIVE FORMALITIES

After the war, Riven/Roger Kirschbaum worked tirelessly, first to become a French citizen, then to have his status as a deportee officially recognized and to seek compensation for damages.

On October 27, 1946, he submitted an application to be naturalized as a French citizen[54]. The was granted a year later, on September 26 1947[55]. Until then, his nationality had been deemed “undetermined”[56]. A few months later, on January 13, 1948, he received his French identity card, which was a major milestone on the road to rebuilding his life[57]. On January 20 1949, he was officially granted the status of “political deportee”[58]: legal acknowledgement of the fact that he was deported grounds of his “race” and a victim of the Nazis. However, at some point between 1949 and 1957, he lost this status. We do not know why.

On July 30, 1957, he began again, by requesting a deportation certificate[59]. His request was granted on August 23, 1957, when he received a certificate confirming that he had been deported to Auschwitz[60]. On September 17, 1957, he renewed his application for political deportee status[61]. This was rejected on March 19, 1959, on the grounds of “incompatibility between the terms of article 1 of the law dated September 9, 1948” and “the applicant having been employed voluntarily by a German firm that worked exclusively for the Wehrmacht”[62]. Riven Kirschbaum had indeed worked in the Weber fur factory, which supplied the Wehrmacht. However, as part of his application for political deportee status, Riven later clarified that he had committed acts of sabotage there.

File on Riven Kirschbaum © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P_580

On December 16, 1983, not long before he died, Riven Kirschbaum wrote to the Secretary of State at the Ministry of Defense, who dealt with veterans’ affairs: “In support of my appeal, I enclose an affidavit from Mr. Max Endel, in which he states that I organized acts of sabotage in the workshops where I worked, even going so far as to burn hundreds of rabbit furs that were earmarked for the manufacture of clothing for the German army. I would also like to point out that I was already working for this firm before war was declared, and I cannot […] be held responsible if it then decided to work for the occupying authorities. As soon as I became aware that the products made in our workshops were intended for such a purpose, I did absolutely everything in my power to reduce our output”[63].

In the witness statement in question, dated May 11, 1983, Max Endel testified that he knew Riven at the Weber factory, where they worked together as cutters during the Occupation. In it, he stated: ” I swear […] on my honor that Mr. Kirschbaum organized a sabotage network in the workshops. He burned and arranged to have burned hundreds or more furs, and it was he who was the first to be spotted by the foreman and was thus obliged to flee”[64].

In parallel with his efforts to be granted the status of political deportee, Riven Kirschbaum filed a claim for compensation with the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1950s. According to his file[65] Riven wore the yellow star from June 7, 1942 to January 28, 1943 (the 8th German order obliged all Jews over the age of 6 in the occupied zone to wear the star as of May 29, 1942)[66]. The file also confirms the dates on which he was interned in various concentration camps: from January 28, 1943 to February 9, 1943, then from July 29, 1944 to April 29, 1945.

Landesrentenkasse NRW 007-008, p. 2.

VII. RIVEN KIRSCHBAUM’S DESCENDANTS

In late May 2025, just as we were finalizing our biography of Riven Kirschbaum, which was still far from the complete story, Riven’s son, Patrick Kirschbaum, contacted us. His son Gary had stumbled across an article about our project. With his help, we were able to piece together the puzzle of Riven’s life, which until we knew he had family had been largely a mystery to us.

We would like to express our most sincere thanks to Patrick Kirschbaum and Catherine Poinson for the family archives they agreed to share with us, and in particular to Patrick for sharing his testimony on June 5, 2025.

De gauche à droite : Abby, l’arrière-petite fille de Riven, Maïlyss, sa petite-fille, Eva, son autre arrière-petite-fille, et Gary, son petit-fils – archives de la famille Kirschbaum

From left to right: Abby, Riven’s great-granddaughter, Maïlyss, his granddaughter, Eva, his other great-granddaughter, and Gary, his grandson – Kirschbaum family archives

Notes & references

Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 8.

[2] Ester and Chaïm Kirschbaum’s marriage certificate, Kirschbaum family archives

[3] Curiously, Riven Kirschbaum only mentions his sister Anna in one official document, his naturalization file, where she is identified as Annie Faure: Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 8. Patrick Kirschbaum, Riven’s son, confirms that Riven never talked about his family (neither his sister nor his parents).

[4] Kirschbaum, Anna, death certificate, Paris city archives, Town hall of the 13th district of Paris. Anna died at the age of 81, on September 18, 1999.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koło

[6] His first name varies in the records from Riven, Ruwen and Ruben to Robert. After the war, he used the name Roger.

[7] Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 5.

[8] https://digital.zlb.de/viewer/image/34115495_1928/1631/

[9] Ein Getto mit offenen Toren, Die Grenadierstraße im Berliner Scheunenviertel, Horst Helas, Centrum Judaicum, 2010.

[10] Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p.18.

[11] Kirschbaum, Riven, ibid.

[12] There is no record of Chaïm Kirschbaum’s deportation from France. According to a document drawn up at the Stutthof concentration camp, where Riven was sent on October 28, 1944, his mother Esther was interned at the Rothschild Hospital in Paris, a Drancy annex camp for sick and infirm people.

[13] Work certificate (Arbeitausweis N°37A), Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21 P 580.176. Riven was then, he wrote in a letter, hired by Jewish furriers who had worked for the German army, making rabbit fur “canadiennes” (warm jackets). He left after realizing that the company was working for the German army. However, his statements about this period are contradictory. Either he took part in sabotage activities within the company (as attested by Mr. Max Endel on May 11, 1983, see later in the biography), or he left after realizing what the management was doing. While Riven explains that he continued to work for his Jewish employers, the French authorities asserted after the war that the employer was Weber, “a German firm working exclusively for the Wehrmacht”. This is confirmed by Riven’s travel pass for the job mentioned in the previous note, which lists his address as 11, impasse Marcès, in file 21 P 580.176..

[14] During the Occupation, the Jewish furriers’ property and tools were requisitioned (“Aryanized”). A handful of Jewish business owners were granted special permits, including for their Jewish workers. After the war, they were deemed to be collaborators.

[15] This information is contained in the file Riven submitted after the war, as mentioned above.

[16] Report by Acting Lieutenant Nowak of the Security Police (Schutzpolizei, Schupo), head of the escort commando, on the escape of eleven people from the deportation convoy on February 9, 1943, quoted in Adam Rutkowski’s article “Les évasions de Juifs de trains deportation de France” (“Jews’ escapes from deportation trains in France”),published in Le Monde juif 1974/1 N° 73, Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, p.10-29 https://shs.cairn.info/revue-le-monde-juif-1974-1-page-10?lang=fr

[17] Volker Mall, Harald Roth, Johannes Kuhn, Die Häftlinge des KZ-Außenlagers Hailfingen/Tailfingen Daten und Porträts aller Häftlinge, A bis K, p. 124.

[18] Adam Rutkowski, op. cit., et Tanja von Fransecky, Fuir un dispositif d’extermination. L’évasion de l’équipe du tunnel de Drancy du 62e convoi de déportation, (you can read the abstract in English here: https://journals.openedition.org/histoirepolitique/13124?lang=en

[19] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV77 APP 77 W 518 – Report on the investigation dated November 19, 1948.

[20] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV77 APP 77 W 518 – Indictment of the accused Ruben Kirschbaum, La Santé prison, June 26, 1944.

[21] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV 77 APP 77 W 518 – Interrogation of the accused Ruben Kirschbaum, La Santé prison, June 26, 1944.

[22] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV 77 APP 77 W 518, ibid.

[23] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV 77 APP 77 W 518 – Report on the investigation dated November 19, 1948.

[24] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV 77 APP77 W 518.

[25] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P 580 176 27852

[26] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid., Department of Statutes and Medical Services, Litigation Office, March 15, 1984. On the uprising at La Santé prison, see Christian Carlier, “14 juillet 1944 ; Bal tragique à la Santé: 34 morts”, (July 14, 1944: tragic riot at La Santé: 34 dead), Histoire pénitentiaire, volume 5. Prisons et camps dans la France des années noires (1940-1945) (Prisons and camps in the dark years of France, 1940-1945). 2. , Paris, Department of Penitentiary Administration, Works & Documents Collection, 2006, p. 28-92.

[27]Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid., affidavit dated July 23, 1982.

[28] Jérôme Scorin (born Skorka), self-published account. See also the book by his sister Régine Skorka-Jacubert, Fringale de vie contre usine à mort, Le Manuscrit, 2009..

[29] Kirschbaum, Riven TD 693 679 104292058 digital archives, Arolsen Archives.

[30] Marcel Ruby, Le Livre de la déportation-La vie et la mort dans les 18 camps de concentrations et d’extermination, (The Deportation Book – Life and death in the 18 concentration and extermination camps) Robert Laffont, p. 265.

[31] Marcel Ruby, op. cit, p. 266.

[32] Marcel Ruby, op. cit., p. 276-277.

[33] Marcel Ruby, op. cit., p.265 .

[34] https://kz-gedenkstaette-hailfingen-tailfingen.de/index.php/das-lager/

[35] Documentation Center, Hailfingen-Tailfingen Concentration Camp Memorial, https://kz-gedenkstaette-hailfingen-tailfingen.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Dokuraumbroschuere-Entwurf-13-FR-100dpi-mittel-rgb-Arbeitsfarbraum.pdf, p. 8.

[36] Kirschbaum, Riven_TD_693_679_104292058. Digital archives, Arolsen Archives, Hailfingen Kirschbaum camp register, Riven_TD_693_679_104292058_Fonds numérique, © Arolsen Archives, Hailfingen register.

[37] https://kz-gedenkstaette-hailfingen-tailfingen.de/index.php/das-lager/

[38] The Natzweiler-Struthof Nazi concentration camp was located in the German Reich-annexed Alsace region of France, not far from Strasbourg. It opened on May 1, 1941 and closed ( in the case of the main camp) on November 22, 1944. Several deportees from Convoy 77 passed through this camp, and many of them died there.

[39] Dachau, not far from Munich (Bavaria, Germany), was the first concentration camp founded by the Nazis. It opened on March 20, 1933. See Amicale du camp extérieur de Dachau, Allach, camp extérieur de Dachau, published by Tirésias-Michel Reynaud, 2022, https://dachau.fr/produit/allach-camp-exterieur-de-dachau/

[40] https://heimatkundliche-vereinigung.de/userfiles/file/Heimatkundliche_Blaetter_60_2013_1824_1871.pdf

[41] Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, 21 P 580.116 ; record dated July 23 1982, “Attestation” for his retirement pension claim. Riven’s accounts of the deportation are also taken from this source.

[42] Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 4 and Joseph Sanguedolce’s testimony, https://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media6006-Libration-dAllach-kommando-de-Dachau

[43] Riven’s son Patrick Kirschbaum’s account, based on the only time Riven spoke to his children, Patrick and Catherine, about his time in the concentration camps, when Patrick was twelve years old (this was also the first and only time Patrick saw his father cry).

[44] Patrick Kirschbaum’s testimony.

[45] Kirschbaum family archives.

[46] Kirschbaum, Riven, French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 18.

[47] Invoice from Maison Dulac, Funeral directors, Kirschbaum family archives.

[48] Source: Patrick Kirschbaum’s testimony.

[49] Fiche d’état civil du 2.12.1988, Kirschbaum family archives.

[50] Source: Patrick Kirschbaum’s testimony.

[51] Family civil status record, Kirschbaum family archives.

[52] Email from Patrick Kirschbaum, June 14, 2025

[53] idem

[54] Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 1.

[55] Kirschbaum, Riven, ibid.

[56] Kirschbaum, Riven © French National archives, 25427X46, naturalization file, p. 7.

[57] Kirschbaum, Ruben CV 77 APP 77 W 518, Report on the investigation dated November 19, 1948.

[58] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P 580 176.

[59] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid.

[60] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid.

[61] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid.

[62] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid.

[63] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P 580 176.

[64] Kirschbaum, Riven © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ibid. This shows just how absurd the reasoning was: while Jews were banned from most jobs, their property and businesses, even the smallest ones, were seized (“Aryanized”) and sold off, their owners never receiving a cent, those who did manage to find a job (or, like Riven, were able to keep their job), were stigmatized after the war by civil servants, not all of whom had a blameless past themselves. Of course, being deported as a Jew had nothing to do with whether or not they worked for German companies. Riven was simply trying to survive, as well as helping his mother. And it was because he was Jewish that he was arrested and deported, not once but twice.

[65] Landesrentenkasse NRW 007-008.

[66] If Riven’s dates are correct, then in June 1942, he was in the occupied zone in the northern part of France, rather than in Lyon or elsewhere in the free zone, where it was not compulsory for Jews to wear the yellow star.

Français

Français Polski

Polski