Sigismond LUZZATO (1873-1944)

This biography was written by Clara Orazi, based on research carried out with her 12th grade students at the Jules Ferry high school in the 9th district of Paris. It was part of a Moral and Civic Education project undertaken in the school library with the help of their history teacher, Ms. Manhes, and the school documentalist, Ms. Mazokopakis.

Sigismond Luzzato. An anonymous name among a whole host of other anonymous names. He was a tailor, a soldier, a son, a father and a husband, but above all an almost forgotten victim of the bloodiest conflict in human history. A victim who, at the age of 71, was deported to the infamous Auschwitz camp, aboard Convoy 77, the last of the major transports of Jews destined for death.

1. The Luzzato family’s move to France

Sigismond Luzzato was born in Vienna, Austria, on June 1, 1873 1. He was the son of Henri Luzzato, who was born on September 25, 1842 in Pazzossy, Hungary, and Jeannette Steiner, born in 1846 in Presburg (the name of the capital of Slovakia, Bratislava, during the Austro-Hungarian period, until 1919), who was a dressmaker 2. Sigismund was described as having dark brown hair and eyebrows, brown eyes, a strong nose, a round chin, a medium-sized mouth and an oval face. He was 5’4” tall as an adult. 3.

Graben, Vienna, Sigismund’s birthplace, in around 1890. Source: Wikimedia Commons, photograph by August Stauda.

Sometime between 1874 and 1876, Sigismond and his family left Austria and moved to Paris. By 1886, Henri had established himself as a men’s tailor, working for private clients, making and selling the clothes himself, on rue du Faubourg Montmartre in the 9th district of Paris. Early in the twentieth century, he moved permanently to number 53. Sigismond may well have been his father’s apprentice at that point. He continued working as a tailor until he died.

The rue du Faubourg Montmartre in Paris, 1930. Source: Press photograph/Agence Rol. French National Library.

53, Faubourg Montmartre today. Source: photo by one of the students

All the evidence suggests that the Luzzato family business was thriving. In 1888, however, tragedy struck. On the morning of December 21, 1888, the mother, Jeanette, died at home at the age of just 42 4. Sigismond was only 15 at the time. She was buried on December 23 in the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris 5.

We have limited details about Sigismond’s educational background. However, his overall academic grade was listed as 3 on his army registration record, which means that he had passed his school-leaving certificate and therefore completed his compulsory education.

On November 30, 1903, Sigismond and his father founded the company “Luzzato et fils” (Luzzato and Son), which made him a director, just like his father.

Sigismond Luzzato became a French citizen in December 1903 6. Sigismond Luzzato became a French citizen in December 1903 6. Sigismond’s first name was written as its French equivalent, Simon, on most official paperwork. Early in the 20th century, he met his future wife, Fanny Marthe Weil 7 who was born on December 17, 1882 in Dambach-la-Ville in the Bas-Rhin department of France. She came from a deeply religious Jewish family in Alsace. She moved to Paris in October 1903, and lived at 32 Boulevard de Strasbourg in the 10th district until she married and moved in with Sigismond.

The Boulevard de Strasbourg in Paris in around 1890. This was where Fanny Weil lived until she married Sigismond. Source: photo by Hippolyte Blancard, Carnavalet museum / History of Paris

32 boulevard de Strasbourg, Paris in 2024. This was where Fanny Weil lived until she married Sigismond. Source: photo taken by the students

On November 23, 1904, the couple agreed to get married in the presence of a notary Albert Pere, whose office was at 9 Place des Petits-Pères in the 2nd district of Paris.

1st photo: 9 rue des Petits Pères, the address of the notary, Albert Pere, early 20th century. Source: Carnavalet museum, History of Paris

2nd photo: 9 rue des Petits Pères in, 2014. Source: Wikimedia Commons, photo by mbzt.

The wedding ceremony took place at 11 a.m. the following day in the town hall of the 10th district of Paris 8. Sigismond’s wife, Fanny, thus became a French citizen. The couple’s only child, Jules, was born a few years later, on April 30, 1907. Fanny Luzzato then left her job to raise her son. Jules’ birth was a turning point for Sigismond, who decided to wind up his first company and start a new one, still at 53 Faubourg Montmartre, together with five other partners.

The Rue du Faubourg Montmartre around the time that Jules Luzzato was born, on April 30 1907. Source: salles de cinémas.blogspot.com (copyright-free image)

2. Military service and the First World War

As Sigismond had been naturalized as a French citizen, he had to complete his military service, as did all French men at the time. He enlisted at the 6th recruitment office in Paris, and his service number was 740. Military service, which for Sigismond, at the age of 30, was his first experience in the army, was split into several stages. Sigismond first served as a soldier in the army until 1904. He was then an army reservist until September 27, 1907, when he was transferred to the Territorial Army. On October 5, 1906, he was transferred to the Territorial Army reserve, in which he stayed until 1913 9.

On August 3, 1914, Germany declared war on France. Sigismond and Fanny Luzzato found themselves in an unfortunate position, due to their ethnic background. The Ministry of the Interior investigated Fanny on account of her German roots, but fortunately she was allowed to stay in France. Sigismond, however, had to leave his family to serve in the army when, according to a decree dated August 1, 1914, he was called up to fight in the First World War.

On August 17, he joined the 33rd Territorial Infantry Regiment. On April 19, 1915, he was transferred to the 2nd Zouave Regiment, which took part in the Battle of Champagne (September 25-30, 1915) and the Battle of Verdun. On January 2, 1917, he was transferred to the 6th Territorial Zouave Battalion and on January 29, 1918, he was made a Corporal Quartermaster. He was transferred to the 13th Territorial Zouave Battalion in February of the same year. This battalion fought on the Eastern Front, also known as the Salonika or the Macedonia Front, in the Balkans (including Yugoslavia, Albania, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire). Many of the French soldiers, including Sigismond remained there until 1919, well after the Armistice was signed 10. According to Fanny Luzzato’s biography, he came home 10% disabled, which absolved him from any further military service. In recognition of his efforts during the war, he was awarded the French War Cross, which was only given to soldiers whose conduct was described as “outstanding”.

3. Between the wars

When the Great War was over, the Luzzato family’s life gradually returned to normal. Sigismond taught his son Jules, the tailoring business. Sigismond sadly lost his father, who was 84, on June 11, 1926. His death had no effect on the company’s income, and it even enabled Sigismond to recruit additional staff, including a new chambermaid, Marcelle Thibault.

During the war, in 1916, Fanny inherited a house in Montmorency, in the Val-d’Oise department of France, from her aunt. After the war, the family might well have used it as a vacation home. Montmorency is less than ten miles north of Paris, and easily accessible by train 11.

Montmorency station, early 20th century. Source: Postcards, Wikimedia Commons

On March 3, 1939, Sigismond witnessed his son Jules’ wedding at the town hall in the 9th district of Paris. Jules married a woman named Andrée Gensburger, who was divorced from her first husband, Marcel André Bouvard. He had abandoned his wife when she was pregnant, and, like them, he came from a Jewish family. She already had a son from her first marriage, Philippe Bouvard 12, who became a well-known TV and radio presenter for the French network RTL, and who Jules Bouvard adopted as his son.

1st photo: Town Hall of the 9th district of Paris in around 1920, where Sigismond’s son Jules married Andrée Gensburger on March 3 1939. Source: Carnavalet museum / History of Paris

2nd photo: Town Hall of the 9th district of Paris in 2020. Source: City of Paris media library

45 rue de Maubeuge in Paris, where Sigismond’s son Jules used to live.

Source: photo taken by the students

4. The Second World War: persecution, arrest, deportation

On September 3, 1939, France declared war on Germany: this was the start of the Second World War.

In 1939, Jules Luzzato volunteered to fight against the Germans, for which he was awarded the Volunteer Service Medal. Later on, he continued the battle in Paris, making clothes for German deserters until 1942, when he was arrested.

Unfortunately for the Luzzato family, France surrendered in 1940, and the Vichy regime took power. The family was severely affected by the government’s anti-Semitic and racist policies. Initially, the family business, which by this time Jules was running, continued to trade. However, as a result of the “Aryanization” legislation, which assigned Jewish property to people who were supportive of the regime, an interim administrator took over the company.

Soon afterwards, Sigismond was banned from working as a tailor, so took in small jobs at home instead. Their property was confiscated, as was their vacation house in Montmorency. Meanwhile, anti-Semitic propaganda and discrimination continued to intensify.

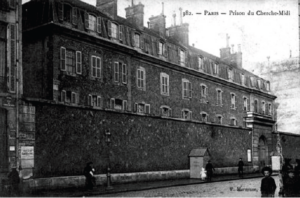

In March 1942, the round-ups began: Jews from France were interned and then deported to concentration camps, primarily Auschwitz. It was at this point that the French police raided the Luzzato home and arrested the couple. Sigismond was interned in the Cherche-Midi prison on July 10, 1942; he was not released until December 21 13, on the same day as his wife, who had been held in Fresnes jail.

1st photo: Cherche-Midi prison (which was demolished in 1966), where Sigmond was held in 1942, at 38 rue du Cherche-Midi in the 6th district of Paris, France. Source: 1910 postcard, Wikimedia Commons

2nd photo: The Cherche-Midi Prison Memorial, with the two oak doors of the old military prison in Paris. Source: Esplanade du Souvenir à Créteil (Val de Marne), 2022. © Photo Jacky Tronel.

The couple had just two more years of respite, although they lived in constant fear, constrained by the anti-Semitic legislation. Despite this nightmare situation, they were able to rejoice in the good news that Fanny, with the help of Kaddour Ben Ghabrit, had managed to have her son released. We would like to take a few moments to write a little about this admirable character.

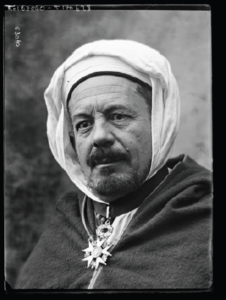

Kaddour Ben Ghabrit was born on November 1, 1868 in Sidi Bel Abbès, Algeria (which was a French colony at the time). In 1920, he embarked on the construction of the Great Mosque in Paris, which was inaugurated on July 15, 1926 during a ceremony attended by the fashionable Parisian elite.

1st photo: Portrait of Kaddour Ben Ghabrit, who intervened several times on behalf of Sigismond, Fanny and their son Jules to help have them released.

2nd photo: The Great Mosque in Paris in around 1930. Founded in 1926 by Kaddour Ben Ghabrit. Source: photo Bridgeman. Images/ RDA

The mosque was intended to symbolize not only the undying friendship between France and Islam, but also the sacrifice of the thousands of Muslim soldiers who lost their lives in the First World War, in particular at Verdun in 1916. Kaddour Ben Ghabrit drew inspiration from these words of the Koran as he battled against Nazism and the occupation of Paris: “When you save a human being, or help a human being, it is as if you are saving or helping the entire human race”. He used his influence to help numerous French Jews, including Jules. As Philippe Bouvard explained to the journalist Mohammed Aïssaoui in 2012, “He had a reputation as a man with great heart and influence. He was one of those rare people who, by virtue of his position and status, was able to talk to the Germans while at the same time appearing to be neutral.”

After he was released, Jules, his wife and their daughter Claudette, who was born in December 1942, went into hiding to escape the authorities. Sigismond and Fanny, meanwhile, who were getting older and were worn out by their time in jail, appear to have given up the will to fight, for they stayed on in their home in Faubourg Montmartre, a place full of memories after having lived there for so many years. They probably never imagined that their final years would be spent anywhere else.

On July 12, 1944, they were once again arrested at their home, this time never to return. Sigismond was 71 and Fanny 62. The janitor in their building and the tobacconist next door witnessed their arrest. They both testified on the same day; February 27, 1947 14, about what happened that day. On July 13, Fanny and Sigismond Luzzato arrived in Drancy camp, where they stayed for 18 days.

Drancy, France, 1941-1944. This multi-story complex served as a transit camp. The overwhelming majority of Jews deported from France were held here prior to their deportation. Sigismond and Fanny were interned here on July 13, 1944. Source: Holocaust Encyclopedia, US Holocaust Memorial Museum

The interior courtyard at Drancy, France, between 1941 and 1944.

Source: Holocaust Encyclopedia, US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Memorial rail car unveiled in 1980 in the Cité de la Muette, Drancy, as a memorial to the deportees. Fanny and Sigismond were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz in a similar cattle car on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. Source: photo by Guillaume Bontemps, City of Paris

The Shoah Memorial in Drancy, commemorating the 600,000 Jews who were deported from the internment camp, 2024.

Source: photo by François Grinberg, City of Paris

On July 31, 1944, they were deported on Convoy 77, the last large transport to Auschwitz. On board were 1309 deportees, 847 of whom died on arrival. The convoy arrived on August 3, and Sigismund and his wife were probably sent to the gas chambers and killed. Sigismund’s death certificate states that he died on August 15, 1944 15, but it should be noted that this date may be inaccurate.

Entrance to the Nazi German concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz Birkenau in Poland 1940-1945. Sigismond and Fanny arrived there on August 3, 1944.

Source: YAD Vashem, Israel, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, photo by Markus Schreider, Associated Press, taken in 2020.

5. After the war

On August 25, 1944, the Allied Forces liberated Paris. This was far too late for Sigismond and Fanny Luzzato, who had already perished in Auschwitz, but it was just in time for Jules, who had been living in hiding with his family and therefore managed to avoid being deported. His second daughter, Anne, was born just a few weeks later, in September 1944. As soon as everything calmed down, Jules began the process of applying for official recognition on behalf of his parents; even though he could not bring them back to life, he could at least ensure their memories were duly honored.

On November 18, 1946, Jules submitted Sigismond’s birth certificate to the French Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War in order to prove that he was a French citizen, which was a prerequisite for “Died for France” status. This was awarded to people whose deaths were said to be “attributable to an act of war”16. The request was granted on September 8 , 1947 17 after a number of administrative mistakes and letters to the Ministry. Jules worked with unparalleled tenacity to ensure that his father’s memory was respected. On June 16, 1958, Sigismond was also granted the title of “political deportee” 18, meaning that he had been deported for political reasons.

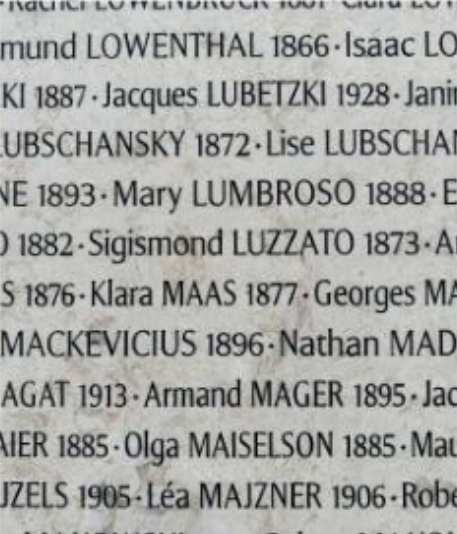

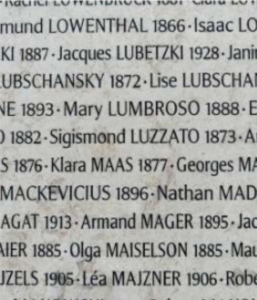

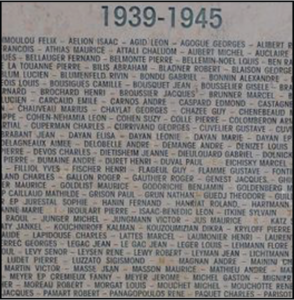

His name is inscribed on the War Memorial in the courtyard of the Town Hall of the 9th district of Paris, as well as on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, where it can be found on slab 26, column 9, line 2.

The students’ visit to the Shoah Memorial in Paris, 2024.

Sigismond’s name inscribed on the Wall of Names.

War Memorial to commemorate those who fought in the Great War (1914-1918) and the Second World War (1939-1945) and also those who “died for France”. Sigismond Luzzato’s name is inscribed on the memorial in the courtyard of the Town Hall of the 9th district of Paris.

Source: Geneanet, Geneawiki, Creative Commons.

Sigismond Luzzato’s name now rests amid a vast ocean of other names, each one a victim of the Shoah, a stark reminder of the terrible bloodshed of this horrific chapter of history.

References

[1] Sigismond Luzzato’s birth certificate

[2] Jeannette Steiner’s death certificate

[3] Sigismond Luzzato’s military service record

[4] Jeannette Steiner’s death certificate

[5] Montparnasse cemetery burial register, 1888

[6] Law Bulletin – naturalisations for the year 1903

[7] Fanny Luzzato’s biography on the Convoy 77 website, written by Simone Zimbardi, with the guidance of her teacher, Marie-Anne Matard-Bonucci.

[8] Sigismond and Fanny’s marriage certificate

[9] Sigismond Luzzato’s military service record

[10] Nadine Bonnefoy, Le front d’Orient: 1915-1919

[11] The railway running between Enghien-les-Bains and Montmorency was called “Le Refoulons” and was in service from 1866 to 1954. There was also a Montmorency-Enghien-Paris (Eglise de la Trinité) tramway, which ran from October 28, 1897 to 1935.

[12] Jules Luzzato and Andrée Gensburger’s marriage certificate.

[13] Record from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War granting Sigismond the title of political deportee.

[14] File from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War and file from the 9th district police station attesting to the collection of two testimonies on the Luzzatos’ arrest.

[15] Sigismond Luzzato’s death certificate.

[16] According to the official definition of the term.

[17] Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War – Deported Persons Registry Office. Inscription on Sigismond Luzzato’s death certificate, Town Hall of the 9th district of Paris.

[18] Ibid. , p. 8

Sources

Sigismond Luzzato

Websites:

- Convoy No. 77, July 31, 1944, Wikipedia page

- Biography of Fanny Luzzato: convoi77.org

- Shoah Memorial Museum, Documentation center: file on Sigismond Luzzato

- Geneanet website: Luzzato family tree

- Biography of Philippe Bouvard edited by the Multimedia library at Saint-Hilaire de Riez

- Biography of Philippe Bouvard, Wikipedia page

- Sigismond Luzzato’s mobilisation sheet

Bibliography:

- Boucard Daniel, Dictionnaire illustré et anthologie des métiers, Paris, Jean-Cyrille Godefroy, 2008.

- Deschaumes Edmond, Pour bien voir Paris. Guide parisien pittoresque et pratique, Paris, Maurice Dreyfous, 1889.

- Wieviorka Annette and Michel Laffitte, À l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, Paris, Perrin, 2012.

Life for Jews in France during the Occupation

Bibliography:

- Adler Jacques, Face à la persécution, Calmann-Lévy, 1985.

- Azéma Jean-Pierre and Bédarida François (dir.), La France des années noires. Tome 2 : de l’Occupation à la libération, Paris, Seuil/Points-Histoire, 2000.

- Blumenkranz Bernhard (dir.), Histoire des Juifs en France, Toulouse, Edouard Privat, 1972.

- Cointet Michèle and Cointet Jean-Paul (dir.), Dictionnaire historique de la France sous l’Occupation, Paris, Tallandier, 2000.

- Diamant David, Des Juifs dans la Résistance française, 1940-1944, Le Pavillon – Roger Maria Editeur, Paris, 1971.

- Doulut Alexandre, Serge Klarsfeld, Sandrine Labeau, 1945: Les Rescapés juifs d’Auschwitz témoignent, Après l’oubli, 2015.

- Dreyfus Jean-Marc, Sarah Gensburger, Des camps dans Paris. Austerlitz, Lévitan, Bassano, juillet 1943-août 1944, Fayard, 2003.

- Grynberg Anne, Les Camps de la honte : les Internés juifs des camps français 1939-1944, La Découverte, 1991.

- Klarsfeld Serge, Le calendrier de la persécution des juifs en France, 1940-1944, 2 tomes, Paris, Fayard, 2001.

- Klarsfeld Serge, Le mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France, Paris, Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, 1978.

- Klarsfeld Serge, Vichy-Auschwitz, le rôle de Vichy dans la Solution finale de la Question juive en France.

Tome 1 : 1942 ; Tome 2 : 1943-1944, Fayard, 1983 (tome 1) and 1985 (tome 2) ; revised in 2001. - Peschanski Denis, La France des camps. L’internement, 1938-1946, Paris, Gallimard, 2002.

- Poznanski Renée, Les juifs en France pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Paris, Hachette, 1994.

- Le Temps des rafles. Le sort des Juifs en France pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Paris City Hall, exhibition catalog, March 1992.

Kaddour Ben Ghabrit

Websites:

- Biography of Kaddour Ben Ghabrit, Wikipedia

- Article in the newspaper Libération, Justes oubliés

Bibliography:

- Aïssaoui Mohammed, L’étoile jaune et le croissant, Paris, Gallimard, 2012.

Français

Français Polski

Polski