Wole, known as Walter, Zavadier 1889-1944

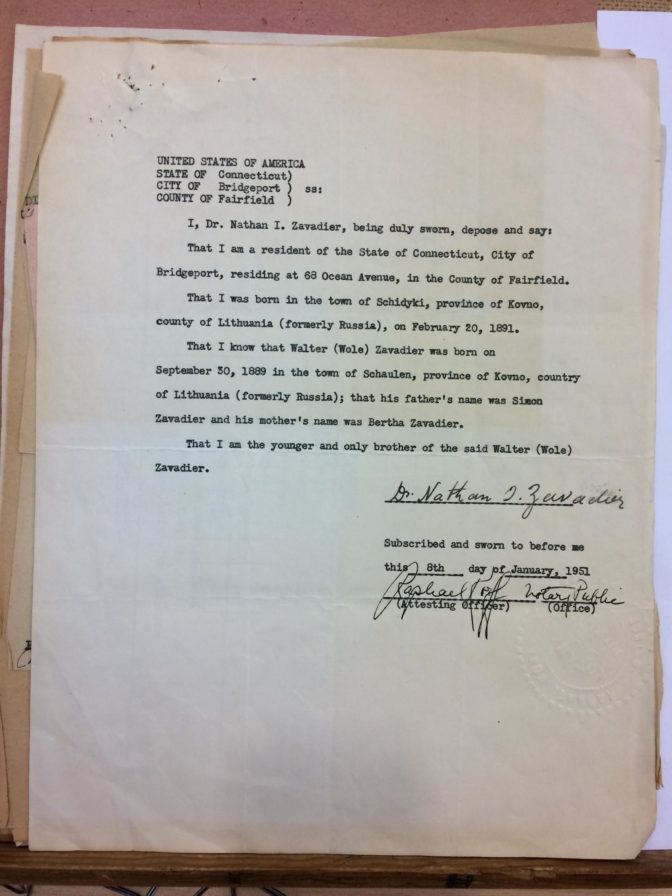

Since we do not have a photo of Wole, known as Walter, Zavadier, we are showing a letter from his brother Nathan, certifying that Wole was indeed his brother, from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, dossier 21 P 551 946.

Walter Zavadier’s life was researched by a group of three students from the International French high school in Vilnius, Lithuania, where he was born. As he spent a large part of his life in Austria and his family was very mobile, the research was quite complicated, especially during the period of the Covid 19 lockdown, when many records departments were closed, and given that the Zavadier family had left traces in the archives in Lithuania, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, South Africa, Israel and the United States. Fortunately, some of the documents are available on several genealogy sites such as jewishgen.org, litvasig.org, ancestry.com, familysearch.org and genealogy.org.il (an Israeli site).

During the lockdown, the history and geography teacher collected documents available on the Internet and contacted archives departments in various countries. Then, after the lockdown, the group of students compiled the biography based on this file and added some historical background information.

Sources

Even though the Zavadiers’ city of origin was destroyed by fire in 1915, with its historical records and Jewish birth registers, numerous sources provide clues to the fate of the Zavadier family:

- the record of Walter Zavadier’s disappearance, held by the Department of Veterans Affairs and War Victims, of the Defense Historical Service, provided by the “Convoy 77” project organizers;

- the “Walter Zavadier” file from the “Moscow records collection” (police files of the Third Republic, kept in the National Archives, after having been confiscated by the Germans, taken to Berlin and from there to Moscow by the Soviet occupying forces), provided by the “Convoy 77” project organizers;

- an extract from the Seine police prefecture’s register of depositions, provided by the “Convoy 77” project organizers;

- an extract from the Drancy search logbook, available on the Shoah Memorial website;

- some Czarist governmental’ registers, held in the Lithuanian Historical Archives, available on the Jewish genealogy sites litvasig.org and jewishgen.org;

- a file concerning the fate of Walter’s mother, who was forcibly “evacuated” in 1915, kept in the Lithuanian state archives;

- the Consular record of Walter’s brother, Nathan, in Switzerland, held in the same archives;

- the registers of departures and arrivals by boat, available on the genealogy websites ancestry.com and familysearch.org;

- the file concerning the legacy of Walter Zavadier’s father, Shimka, available on the same websites;

- several South African medical journals mentioning Shimka, from the 1910s until his death in 1943, reproduced on the Internet;

- the dossier relating to Walter Zavadier’s properties in Vienna, which were looted by the Nazis after 1938, held in the US archives and available on the Internet;

- a file relating to Walter Zavadier, held in the German Federal Archives;

- files relating to Nathan Zavadier and his mother Berta in the Swiss Federal Archives, where they scan documents free of charge on request;

- files relating to the looting of the Zavadiers’ properties, held in the Austrian State Archives and the Vienna City Archives;

- registration documents of the inhabitants of Vienna (Meldezettel), available on the website familysearch.org;

- personnel registers of the Technical University and the University of Agriculture in Vienna, copies of which were kindly sent to us by these two institutions;

- a file on Nathan Zavadier, doctor and poet, held in the archives of the Swiss Writers’ Society in Bern, Switzerland.;

- Nathan’s letters to an Austrian friend in 1929-1933, held in the Vienna City Hall Library, copies of which the staff kindly sent to us and for which we thank them.

The Zavadiers, a Jewish family from Šiauliai

Walter Zavadier was born in Šiauliai, Lithuania, which was then in the Russian Empire, on September 30, 1889, under the name “Wole”.

Lithuania had been home to a very large Jewish population since the late Middle Ages and the Modern Era, when the country stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Ukraine. It had opened its doors to Jews expelled from other European countries, whose craftsmanship and commercial skills were to contribute significantly towards the development of the Grand Duchy. In the second half of the 18th century, the Grand Duchy was annexed by the Russian Empire, which then found that its western periphery included numerous shtetl, Jewish towns and neighborhoods, which accounted for a large part of the urban population. Thus, at the time of the 1897 census, Šiauliai was the second most populated city in the Kaunas government area (present-day Lithuania minus the Vilnius region) with 16,128 inhabitants, of which 6,978 (43.3%) were Jews.

Šiauliai is known as a Phoenix-like town, having had to rise from the ashes and rebuild itself after a series of large fires, particularly those of 1872 and 1915. The records of the local Jewish community disappeared in the flames. Šiauliai is also well-known for having been shaped by the Industrial Revolution, which led to the development of the Chaïm Frenkel tannery, the largest leather factory in the Russian Empire.

Wole’s father, Shimka Zavadier, was neither a trader, nor an artisan, nor an industrialist: he was a doctor, having studied in Jewish schools in Lithuania and then at the University of Kharkov. Wole’s mother was called Berta, and she had a second child, Nathan, in 1891. The family must have been relatively well-off, since all the members of the family had a bank account in 1905.

Photos of Šiauliai in the Belle Epoque, postcards published in the newspaper Lietuvos Rytas, https://kultura.lrytas.lt/istorija/siauliai-pries-simta-metu-pamatyk-miesta-atviruku-kolekcijoje.htm

The father’s departure

The family’s migration started with Wole’s father. In 1891, Shimka moved to South Africa, where he established himself as a doctor.

His departure was part of a great wave of migration. Under the Russian Empire, the Jews’ status declined greatly during the 19th century, especially after the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881. This was used as a pretext for pogroms (although not in the area of present-day Lithuania), and between 1881 and 1914, more than two million Jews left the empire. A large number of Lithuanian Jews migrated to South Africa. Between 1885 and 1914, more than 11,000 Jews left the Kaunas government area, out of a total of just over 14,000 in the entire Russian empire. South Africa was among the “new countries” that particularly attracted European and Jewish colonization, as did the United States, Canada, Latin American countries and Australia. Living conditions there were poor, and migrants generally performed physical work, which was hard but better paid than in Lithuania. Shimka Zavadier, however, who was better educated than the majority of migrants, set up as a doctor. Additionally, according to what he said at the time, he had not fled the anti-Jewish persecution but rather the monotony of life in the shtetl. Perhaps he had also fled family life, given that he left his family behind in Lithuania.

Shimka Zavadier integrated so well into local society that he participated in the Second Boer War against British rule, from 1899 to 1902. He fought on the losing side, and at the end of the war, in 1900-1901, Shimka was interned in one of the first concentration camps in history, built by the British for the Boer prisoners. He was thus classified as “extremely anti-British”. Even though the living conditions were very harsh, the camps badly managed, the prisoners poorly fed and often victims of typhus or measles, Shimka survived and returned several times to Europe, most notably in 1911.

A concentration camp for Boer prisoners

The Zavadier brothers

Shimka Zavadier must have sent money to his family back home, which enabled his sons Wole and Nathan to go to high school in St. Petersburg at the beginning of the 20th century, even though Jews could only settle in the capital if they had special permission, and a maximum of 3% of places were allocated to them in the local educational institutions. The two brothers therefore probably had an excellent academic record.

While in St. Petersburg, Wole and Nathan would have witnessed the 1905 Revolution. This began over the autocratic regime of Emperor Nicholas II, following Russia’s defeat by Japan and the Red Sunday Massacre of January 22, 1905, when peaceful demonstrators wearing icons and portraits of the Czar were machine-gunned by soldiers outside the Winter Palace. Rebellions then broke out throughout the empire, with strikes, protests and calls for independence in outlying areas. A Soviet worker movement emerged in the capital. However, Nicholas II finally restored order by promising the election of a parliament, the Duma, and by resorting to intensive repressive measures.

The Demonstration of 17 October 1905, Ilia Répine

When his father’s inheritance was settled after the Second World War, Nathan described his brother as “of a vagabond disposition”, “in poor health” and exhibiting “communist tendencies”. Perhaps it was during the 1905 revolution that Nathan had noticed these tendencies in his brother.

In 1909, Wole enrolled as a student at the Technische Horschule (University of Applied Sciences) in Vienna, to study engineering. In Russia, there was a numerus clausus (number limit) for Jewish students at the university, hence the interest in studying abroad. In 1910-1911, his brother Nathan joined him, but then left in 1912 to study medicine in Zurich, where he completed his thesis in 1918.

In Vienna, during his studies at the Technical Institute, Wole changed his address three times, living at 18/21 Kleinen Neugasse in the 4th district, then at 16/10 Müllnergasse in the 9th district, and finally at Lichtensteinstrasse, still in the 9th district. He also started to call himself Walter. After graduating as a chemical engineer in July 1913, he continued his studies until 1919-1920 at the Horschule für Bodenkultur (the Institute of Agronomy). At the end of his course he was living at 29 Säulengasse.

Separation and reunification

Wole Zavadier and his brother thus spent the Great War abroad, Wole living in Russia and Austria-Hungary, which were enemy countries, yet this did not prevent him from continuing his studies. His father, Shimka, is mentioned in some medical publications as having been living in the Netherlands, the original homeland of the Boers.

Only his mother, Berta, stayed in Lithuania until 1915, when she was forcibly evacuated to Poltava, in the Ukraine, when the Russian army set fire to the city of Siauliai as the Germans approached. On a broader scale, the Russian authorities “evacuated” large numbers of Jews living near the front in 1915, as they were not considered to be “reliable”. Latvia and northern Lithuania were particularly affected by these evictions.

The German Army arriving in Šiauliai, in flames, 1915, Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1971-018-03 / Kühlewind / CC-BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5482589

Once the war was over, Berta was able to leave Soviet Russia in 1922 and go to Vienna, where her husband and son Wole were waiting for her. Shimka seems to have bought some real estate in Vienna, so that the family could make a living from it. He himself eventually returned to South Africa.

Wole’s nomadic, vagabond side was still evident after his studies, as the Vienna Residents’ Register shows: in 1927, he left his home on Säulengasse Street although it is not clear if he was working at the time; in 1933, the authorities no longer knew where he was. By 1936-1937, Walter had become an Austrian citizen and was living in Klosterneuburg, a town north of Vienna, where he may have been working as an agronomist.

Nathan, meanwhile, remained in Zurich, where he published poems in German in addition to his work as a doctor. He was unable to secure a permanent position, however, having had only a series of temporary jobs. In 1932, he tried to return to Lithuania, but he was not allowed to practice medicine there without a Lithuanian diploma. The letters he wrote to an Austrian friend in 1930-1933 show that he was increasingly afraid of the effects of the economic crisis and the rise of Nazism in Germany, even before Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933: “The Europe we knew, or perhaps did not know well enough, no longer exists. Even here we can sense these violent echoes.” Nathan ended up leaving for Palestine in 1935 or 1936, but seems to have come back in 1938. When the Second World War began, the British authorities forbade him and other foreign Jewish doctors from practicing there, ostensibly because he no longer had a proven local address. Nathan returned to Switzerland in 1938 or 1939, perhaps because of the Anschluss that was endangering his mother and the family‘s assets in Austria.

Identity photo of Nathan Zavadier at the beginning of the 1930s, from the Lithuanian State Archives

Exile

In Austria, the situation deteriorated. From 1934 on, an „austo-fascist“ dictatorship took over the country and lead to the arrest of many communist activists. Walter Zavadier who was a sympathiser, according to the account of his brother after the war, departs in direction of Switzerland in 1937 and then to Paris.

In 1938 Austria is annexed by Nazi Germany – it‘s the Anschluss. The Jews in Austria are now subjected to the Nuremberg Laws, depriving them of their citizenship and forcing them to declare their assets (April 26 1938) followed by the Kristallnacht pogroms in the night from October 9 to October 10, as well as the newly adopted anti-Jewish mesures aiming to exlude them from economic and social life. In November 1939, Berte died. The two buildings that were both in the name of Walter have been looted.

In Paris, Walter can survive thanks to the frequent money payments made by his father. But during the outburst of the Second World War he is internated in one of the Third Republic‘ camps for foreigners located in Meslay-du-Maine and destined for German and Austrian citizens. However, he was released on January 12, 1940, and settled in Paris. From July 1, 1941, he stayed at the Hotel Welcome 31, on rue Sauffroy, in the 17th district. He still lived on money sent via Switzerland by his father, who later died on December 1, 1943, and then by his brother. Nathan, who came back to Switzerland in the late 1930s, decides to go to America in 1940, where he can finally live a normal life as a doctor, while still publishing poems in the press.

Walter’s deportation

On July 1, 1944, the German authorities summoned Walter Zavadier to the finance office, in connection with a transfer sent by his brother via Switzerland. On July 5, he wrote a letter to the owner of the hotel to inform her that he was in the Santé prison. On July 27, a second letter informed her that he was to be sent to Drancy. After three weeks in prison, on July 21, he was transferred to the cells at the Seine police headquarters, and then sent to Drancy on July 29.

On July 31, Walter Zavadier was sent from Drancy to Auschwitz. The French authorities recorded the date of his death as August 5, 1944, but this was an arbitrary date, being the 5th day after the departure of the train. The same applied to all deportees for whom the exact date of death was unknown. In fact, the majority of the deportees were gassed immediately upon arrival, on August 3.

After the war, Nathan Zavadier, who had become a U.S. citizen in 1946, had Walter’s death acknowledged by the French authorities and began proceedings in South Africa, as well as with the American occupying forces in Austria, to try to reclaim the family’s looted property and his father’s estate. He ultimately died in 1960, after many years of mental anguish, tortured by paranoia, which was perhaps related to the persecution that his family had suffered. In his will, made in 1957, Nathan bequeaths 1000 dollars to the Israel government so that trees will be planted in memory of his brother.

Contributor(s)

Three students from the French International High school in Vilnius, Lithuania, under the guidance of the history teacher, Yvan Leclère.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Superbe travail !

I recently came into possession of a suitcase containing my grandfather’s correspondence and genealogical research. Mainly from 1942 till 1957. It includes numerous letters between himself and Dr. Nathan Zavadier! Some of it is astonishing. Much of the correspondence deals with the family tree (it would seem that we are possibly related), and my grandfather’s attempts to locate a book written by Nathan’s grandfather. Would you be interested in this material?

David Fenster