Evelyne KANN

We are a group of 9th grade students from Les Blés d’Or middle school and we are going to tell you the life story of Evelyne Kann, who was deported during the Second World War. We chose to write about this young girl because at that time, she was a similar age to us. In order to better understand what happened during the war, we were lucky enough to go to Berlin and visit the Sachsenhausen camp. We also visited the Drancy internment camp and read a number of books about the deportation of Jews such as “Retour à Birkenau” (Return to Birkenau) by Ginette Kolinka. We worked as part of the Convoy 77 project, which aims to keep alive the memory of the people who were deported on this convoy, which left Bobigny station on July 31, 1944. The records provided by Convoy 77 and the video made by the Shoah Memorial in Paris helped us a great deal in writing Evelyne Kann’s biography. Lastly, we decided to write the biography in the first person in order to bring the story alive.

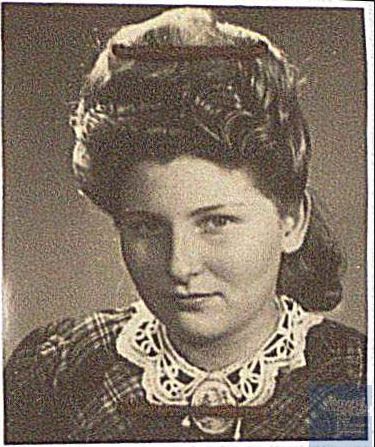

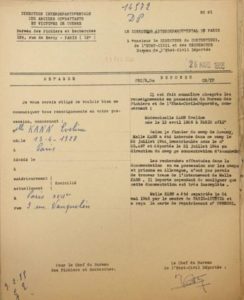

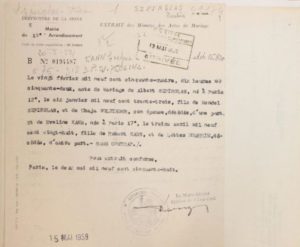

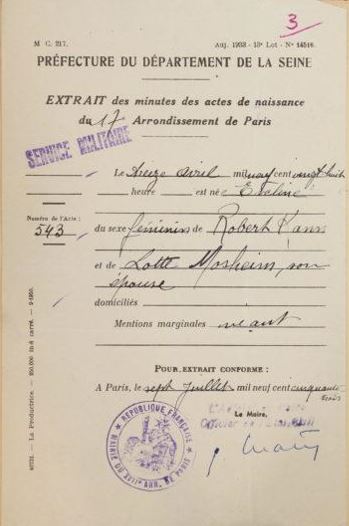

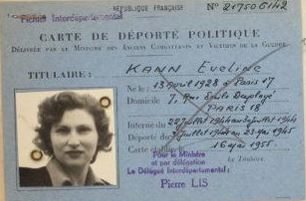

I was born in the 17th district of Paris on April 13, 1928 and I lived through the time of the Holocaust. My father’s name was Robert Kann and my mother was Lotte Mosehem. They met each other completely by chance on the platform at Zurich railroad station. I was an only child. My father was a businessman and he earned a good living. I started going to a private Catholic school in Neuilly, although I never took catechism lessons because I was exempt. I had a very secular education and I was never a practicing Jew. I had a happy childhood even though I lost my mother, who suffered from asthma, at the age of six and a half, and my father died two years later. At that point, I was totally destitute! I did have grandparents, who lived in Berlin, but they didn’t want me to go there in the midst of the fascism and anti-Semitism that was prevalent in Germany at the time. It would have been better if they had, but they had no idea of that at that point. I also had an uncle, who was a Protestant, who took care of my family until he died in 1939. At his funeral, my aunt decided to leave, together with my mother, for Scotland, where we also had family, given that my grandfather had died in 1935. They were lucky enough to get a visa and board the last plane from Berlin to London, but they were unable to come to collect me from France.

Soon after that, I was placed in the Rothschild orphanage and sent to high school, so I didn’t suffer too badly. There I had a very religious upbringing; I learned Hebrew, had my Bat Mitzvah ceremony and went to synagogue every week. The only memories I have are of singing religious songs. We were very well taken care of. The boys were separated from the girls and stayed on different floors.

In 1939, due to the war, we were taken to Berck, on the north coast of France, where we were to stay until 1940. The Baroness de Rothschild even chartered a boat to take us to Canada, but we were prevented from leaving by the advancing Germans. I stayed at the orphanage until February 1943. We ate very well throughout my time there. There were around a hundred of us, including a dozen or so German women and a similar number of Austrian women who had arrived in 1938, having been rescued from Vienna, and there were people of other nationalities as well. I was classed as a “J3″, which means that I was among the teenagers from 13 to 18 years old, so we had good rations. I was aware, nevertheless, of what might happen to us due to my family background. My grandmother continued to write to me; I received her letters via the Red Cross until she died in 1943. I also witnessed two series of arrests in the orphanage: in July 1942, they came to fetch the German and Austrian women, and that was when we first encountered the police, shouting out orders. I lost some good friends. And then in February 1943, when we were in the dormitories, we suddenly saw lights everywhere and heard the shouts and protests of the manager, Mr. Cohen, who tried to reason with the policemen, saying, “Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?” The officers retorted that they were just doing their duty, and that it was in fact their job! We were all shocked but at the same time pleased to have a manager like that. After that, the orphanage was closed and we were placed in the children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews), firstly on rue Lombardie and then on rue Lamarque.

Despite moving between homes, I continued to go to the same school in the 12th district of Paris, opposite the town hall. The teachers showed me how to get out the back way, just in case anyone came to arrest me. During class, I kept my yellow star hidden and when I took the subway and walked to school, I wore the star but carried books in front of it and rode in the last car of the subway so as not to cause any trouble. Besides, I was blonde with blue eyes, so I didn’t stand out. I’m not sure if there were any other Jewish girls at the school. That year, 1943, went quite smoothly. I had a normal school routine and I was a good student.

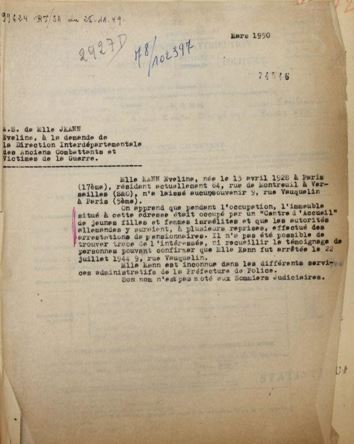

That same year I was sent to the children’s home on rue Vauquelin because I was too old to stay in the home on rue Lamarque. Everyday life was very similar. I remember that there was a police department on the corner, but no one ever bothered us, even when they saw that we were hiding our yellow stars.

In 1944, a major event in the history of the Second World War took place: the Allied landings in Normandy during the night of June 5-6, 1944. The Allies were made up of Americans, English, Canadians and some French. They succeeded in pushing back the Germans and began the process of liberating France. After hearing this news, we thought that we were saved and that we would soon be free of the German occupation. Just after this, some people who worked in Drancy camp came to see the manager and advised her to split us up so that we would not all be arrested. They seemed worried about keeping so many of us together. Only a few of us left, however, because we wanted to finish our school year in peace. We really hoped that no one would come after us !

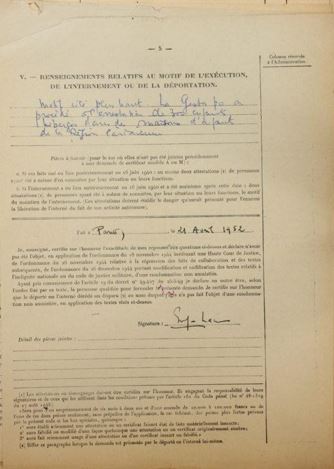

Suddenly, on July 22, 1944, at 5:00 a.m., Aloïs Bruner and two German officers arrived: they had scoured the neighborhood looking for Jews to arrest. When they didn’t find anyone, they came to the home to arrest us. Next to the home was a convent where we could take refuge if ever the Germans came to arrest us, but when they arrived, the concierge opened the gates too wide, wide enough for them to get through. While the Germans were searching the home, we were asleep on the top floor. One of the Germans was standing at the bottom of the stairs on floor below when a supervisor tried to go up. The soldier asked her what she was going to do, to which she replied that she was going to wake me and two other girls. The soldier was astonished, and that was how we were found out. It was a shame, because otherwise we might never have been arrested! Everyone was taken away, even the manager. We were asked to hurry up and get dressed and then we had to leave, children and staff together.

We were taken to Drancy camp and placed in the deportation block. We already knew that Drancy was a transit camp, so we also knew that we were to be deported. We stayed there for a week but I don’t remember much about it. We young people stayed together. We were hardly allowed to do anything except to go down to the courtyard at the foot of the block we were in, which was deportation block 3. A week later we were taken by bus to the Bobigny railroad station along with some other people who had been arrested around the same time as us, although we didn’t know where they came from. The commandant of the Drancy camp arranged to give us extra food and our cattle car was not locked. There were sixty of us, all crammed in together. There were a lot of young people but also some families. One family was made up of two children and their parents. Only the boy was selected to work, and he eventually made it out of the camps alive. He was a cousin of Georges Mayer, the president of the Convoy 77 association. Our convoy was number 77 and it was July 31, 1944. We spent three days and two nights on the train. It was very hot and the tiny openings in the wagon were too small to let in enough air. The smell was overwhelming even though the doors were opened sometimes when we stopped at a station. As I had heard on Radio London, during a two-month period when we were kept hidden in people’s homes to avoid being rounded-up, I knew where we were going and I tried to tell myself that I had only 15 days left to live! But I was only 16 years old and I was oblivious!

When we arrived, we were at the far end, between two camps, so we did not see the gates that are always depicted as the entrance to Auschwitz. As soon as the train stopped, we heard them shouting the order “Raus”. Fortunately, I knew a few words of German, which helped me to understand and translate the orders to my comrades. We were not to move. I was shocked to hear one of the deportees who was “welcoming” us cry out “Mom” when he saw that his mother was on our train. That really upset me! Since we were in good health, we were selected to work but we didn’t realize that we would never see the others again; everything happened so quickly! We were taken away and then into a large room, where we had to take off our clothes in front of a group of men. As young teenagers, we found this very embarrassing, but we got undressed and went into the showers. After that, we were shaved all over. Meanwhile, we asked some other deportees where the others were and they pointed up to the sky. We immediately realized what was happening to them! We were then taken into the women’s camp. Yvette Levy told me that before we arrived at the camp, the camp was already overcrowded, and they had gassed two thousand Gypsies to make room for us. After having taken a disinfectant shower, they threw us some old rags to wear and took us to a barrack for a period of quarantine. We were booked in two weeks later and I thought the fact that we were put on a register meant that they intended to keep us there, and from that moment on I started to regain hope. My girlfriends all said that we were going to die but I insisted that we were not because we had been put on a register and that they would not have done that if they were going to kill us! A few days later, another transport arrived. I think it was Convoy 78, which came from Montluc, in Lyon, and the girls who were on it were moved in with us. Our hut was the only French barracks in Birkenau. The fact that we were all young meant that we wanted to believe that there was still a future, and this gave all the girls in a bit of a morale boost. We told ourselves that ours had been the last of the convoys and that they still needed manpower, so we had to hold on! Soon afterwards, we heard that Paris had been liberated. Some Italian women arrived a little later and we made friends with them. They confirmed the news. The word went round during a roll call, which lasted for hours.

From the camp, which was next to the railway line, we saw the deportees from Terezin arrive, including the musicians who were killed in the gas chambers as well as all the Hungarians. We stayed for three months in Auschwitz, where we sometimes had to carry bricks from one place to another. However, since we were in quarantine, we were left outside without a kommando to supervise us.

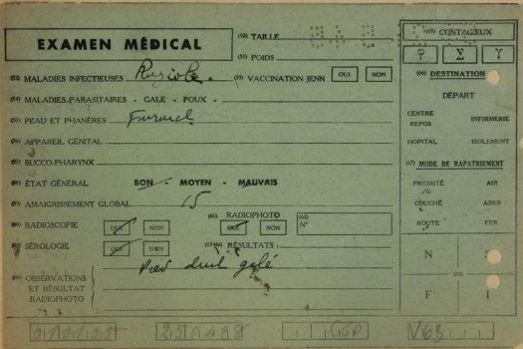

I also remember that at one point I was taken to the infirmary because I had developed red pimples all over my body (the medical form describes this as “roseola”) and I stayed there for a fortnight until it cleared up. There was a girl nearby who had typhoid fever. I was fortunate because there was some milk available in the infirmary. There was a girl nearby who had typhoid fever. The head of my block was Polish and she was quite kind. In fact, she was the only one of the heads who was nice. l also remember Mengele coming to see us to make selections. We had to line up five at a time in the roll call yard. l had nearly died before I left due to an appendicitis operation, which had left me with a huge scar. The SS would look at this scar and were reluctant to send me to the selection, so I never had to go. I was blonde, blue-eyed and fair-skinned, so I had no trouble with the SS and they only hit me once during the time I was there. As far as morale was concerned, I was fortunate, in a way, to be an orphan because it meant that I didn’t have to think about what they might have done to my family, which some of my girlfriends did. This got them down, but between us, we made it through.

As for my weight, I was about 120 pounds when I was arrested and about 95 pounds when I was released: I had never eaten too much and that worked in my favor. Other than when I first arrived, I was never shaved again, so when I came back to France, at least I had some hair. This was important, because the first time it happened it affected me greatly. My tattoo was done by a woman who did it very neatly and made the numbers small, and it was on the inside of my arm. It didn’t affect me too much because I always felt that it was a sign of hope, in that if they tattooed us it meant they were going to keep us alive, and I managed to forget about it after I was released from the camps.

We stayed in Birkenau for three months. Three days before we left for another camp, I remember that we had to walk from Birkenau to Auschwitz, which was a two-mile walk, just to take a shower. We also had to go back on foot, and got very dusty. We rarely went to the showers, only when they wanted to disinfect us, and in between times we tried to keep clean by washing ourselves under the rusty taps in the barracks. When we left, they gave some more clothes and we were sent by train to Germany. We wondered where we were going. It turned out to be Czechoslovakia. It was a kind of big farm with a three-storey building that had been converted into a camp and there was no crematorium there. It had an entrance gate, was enclosed by barbed wire fences and there were some showers. We slept in dormitories, in three-level wooden bunks. As for food, the guards brought us soup, which was as bad or worse than it had been in Birkenau: some of us, myself included, had to force ourselves to eat. I wore size 36 shoes and it was difficult to find any that were the right size for me, and due to the harsh winter, one of my feet froze. On the first day, a man came to select the women they wanted to work. I was fortunate enough to be chosen to work indoors because with temperatures of -22°F (-30°C), those who were working outside, carrying weapons, really suffered. We began to work for real there. The factory was in Kratzau in the Sudetenland.

The day went like this: we got up at 5 o’clock in the morning and walked in line to the factory, which was two or three miles away in the countryside. I worked at a lathe, making weapons. The factory was an old hosiery mill that had been requisitioned from its Czech owner. We worked all day and then in the late afternoon we went back to the camp, where we were counted again in the roll call area. After that, we could go back to our barracks. During the day, we worked alongside skilled Czech employees. Between us, we sometimes managed to make the machines break down. We were able to talk to them a little, but only discreetly, because German guards were watching over us. We did three eight-hour shifts: with some people working from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m., to keep the factory running twenty-four hours a day.

One day, as I was coming back from the camp with Yvette (Lévy), Suzanne, Janine and two other girls, an SS woman slapped Janine, and Janine slapped her back! After that I thought it was game over for us all and that I would be sent to the crematorium but in fact the guard said nothing. I was amazed.

On another occasion we arranged a potato “theft” in the kitchen. As I was working at the forge at the time, I asked the German blacksmith to cook them for me and I brought them back to the camp to share with the others among us. There were about fifteen of us from the Vauquelin home and we were a tight-knit group.

We had heard that the Allies were advancing. Most of the news I heard about the war came from the Czech workers in the factory. There were also some people who had been deported from Lorraine whom we met from time to time and with whom we shared information. As a result, we knew a bit about what was going on. In around February or March 1945, we began hearing gunfire, so every day we were hopeful that something would happen.

There were two escape attempts, both by Czech girls: the first time, the girl went to an SS house, so she was returned to the camp, but the second time, two Czech girls who had been deported from France escaped and managed to get to Switzerland, where they passed on some information about us.

At one point our group had a bit of luck. We were about 55 miles from Dresden and we could see the bombing, which made us very happy because the Germans were being attacked. We saw this as a form of vengeance: innocent Germans were being killed, sure, but they were doing the same thing to us, weren’t they? What had we done wrong, except for being Jewish? One day an SS woman asked one of my girlfriends why we were in the camp: “I heard you were criminals?” she said, and my girlfriend replied: “No, we’re here because we’re Jews. We haven’t done anything wrong, we’re just Jews! The guards were shocked, and it made them stop and think, but nothing changed.

One morning, nobody came to wake us up and suddenly someone from our group came in and said “It’s over, we’re free, the war is over!”. We stayed put at first because we were wary of the Russians. We then made contact with the mayor of Kratzau, and some of the girls would go to collect food and bring it back to the camp so that we all had something to eat. We couldn’t eat too much, however, because some girls got sick due to overeating. They set up a train to take us to the American zone in Prague. We took the train, arrived in Prague, took another train and then walked from the Russian zone to the American zone. When we arrived in the American zone in Pilzeine, the Americans initially wanted to transfer us to a camp but we refused, saying that we didn’t want anything more to do with camps. A group of six or seven of us set off again on our own and soon met some French soldiers, who offered to put us on the next train to France. We agreed immediately, of course. Then when we got to somewhere in Germany, the railway tracks were broken so we got a ride to southern Germany in some American trucks. There, we bumped into the French army again, and the soldiers put us on a train to Metz. When we arrived, they were screening people, but since they didn’t know anything about our group, they sent us on to Paris. We arrived in Paris on May 24. We went to the reception center at the Lutétia hotel with the same few belongings that we had been carrying since we set off. Some of my friends were really thin and only weighed about 60 pounds, but I had lost very little weight and was about 95 pounds.

At the Lutetia hotel, they asked us a lot of questions because we didn’t have any ID on us. We had no papers at all. Our replies to the questions were taken into account in deciding where we should go next. We were immediately taken to a home for young people run by the OSE (L’Oeuvre de secours aux enfants or Children’s aid society). At 16 years old, we were still minors, so the government could not just let us loose on the streets. We ended up in a home on rue Montévidéo. My aunt, who was in Scotland, was notified that I was there. I also had a cousin in Paris, Robert Javelon, who was quite well-known. He had been involved in rescuing children before the war, sending them abroad on convoys. My aunt asked him to deal with everything because she herself was battling with the British authorities in order be able to work and earn money. She had to wait until she became a British citizen, which was a long process and, in the meantime, she wasn’t allowed to take me in. That is why I was placed in an OSE home. People who had family members went to stay with them and those who didn’t went to children’s homes. While I was there, I was encouraged to go back to school. I didn’t want to go because it meant I would be with girls two years younger than me, but in the end, I went to a school in Saint-Germain where I met up with another deportee, Hélène Vexler, and some other children whose parents had been deported, so I wasn’t the only one in this situation. I went on to do my Baccalaureate. One of the head teachers at Saint Germain knew some young people who had been in the Resistance and she put me in touch with them. That’s how I met my future husband, Albert. Only one member of his family had been deported; the others had been kept hidden.

I received a grant, so had some spending money, but aside from that, the OSE took care of me until I came of age, which at the time was when I turned twenty-one. After that, I had to find a job in order to earn money and support myself, so I became a secretary. I got married on February 20, 1954 and thus became Mrs. Szpirglas. I went on to have two sons, but I didn’t want to talk to my children about what I had been through; it would have been too much for them. But then my oldest son, when he was five, saw my arm and asked me what was wrong with it. He didn’t understand why he was not allowed to write on his arm yet I had this writing on mine! I told them that some very wicked people had done it. My sons used to tell me that I had nightmares at night, and that I cried out, but I could hardly believe that I was still dreaming about it. I knew that this upset them, but it was too painful for me to talk about it all. As much as I wanted to spare them, I know that they were affected by that.

I lost touch with my girlfriends after the war, but we got together again fifteen years later and ever since then we have met up on May 8th every year to celebrate the birthday of one of our friends. During those fifteen years, I just wanted to forget about what had happened. I only agreed to be interviewed to please Yvette Lévy. She was with me in the Vauquelin home, having arrived there after Noisiel was bombed. Her parents were living in hiding because they were wanted by the authorities. She used to come to stay overnight at the Vauquelin home, where she helped to take care of the Jewish children, so that’s how we met. We were deported together and became friends. It was her, Yvette Deyfrus, married name Lévy, who persuaded me to give my testimony. I didn’t really suffer too much during the war in comparison to other people who lived through it and who were less fortunate than me.

I am very pessimistic about the future. I feel that it is important for teachers to take part in projects such as this, because we survivors are very old now and we won’t be here for much longer.

In 2020, Evelyne was interviewed by France Info. She was about to leave, together with her son Bruno, a music teacher in Le Mans, to accompany a group of students on a visit to Auschwitz.

Sources

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77

- Testimonials of Béqui Pisanti, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, which are available on the Shoah Memorial website

- Books by Simone Veil, Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah ; Ginette Kolinka, Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant, Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan, J’ai pas pleuré

Français

Français Polski

Polski