Élie SEBAG

This biography was written by the 9th grade students from the Les Blés d’Or middle school in Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, with the help of their History and French teachers, Ms. Garillière and Ms. Jorrion. We chose to write the biography of this person because he had the same surname as one of the students in the class. That was our starting point. The research and analysis work was started before the Covid 19 lockdown, but the biography was written during the lockdown.

Élie Sebag’s father, Benjamin was born in 1879, whereas his mother, Maissa, whose family name before her marriage was Turjman, was born in 1888. They lived in Tunis and brought their first son, Félix, into the world in 1906, followed by Albert and Jules in 1908, Juliette in 1911 and Alexandre in 1913. Their father was a fairground worker. Between 1913 and 1915, the family moved from Tunis to live in Marseille, in France, where René was born in 1915, then Marcelle and Estelle in 1918. They then went to live in Paris where Élie was born in 1920, in the 4th district, then Simon in 1923 and finally André and Victor in 1926. They were a large family, with 12 children, who lived in Paris from the end of the First World War onwards. As the time of the 1926 census, the Sebag family could be found in the 12th district, in the Picpus area, at 10 rue Touneux. The older brothers were working. Félix was a driver and Jules and Albert were printers. In 1931, after the crisis of 1929, the father was out of work, as was Jules. Albert had become a laborer, Alexandre was a hatter and René was a printer. In 1936, the father was a laborer, and Alexandre was unemployed, as was his brother René. Marcelle was working at Place Daumesnil and Élie at the zoo.

Élie Isodore Sebag was born on March 11, 1920 in the 4th district of Paris. During his childhood, he lived in an apartment with his large family. He undoubtedly went to school until he got his school certificate at the age of 14 because in 1936, he was already working at the zoo. Which school did he go to? We didn’t have time to find out. Was he a good student? Did he stop studying when he could have gone on to middle school? Or did he quit school because he didn’t like studying? The family was large, so everyone had to be fed. The zoo was a twenty-minute walk away. What did he do at the zoological garden? Did he take care of the animals? Or maybe the plants?

In the meantime, the family must have been having a hard time because some of them, who would normally have been earning, were unemployed. There would have been happy times too though, such as weddings. We discovered that Felix, the brother born in 1906 in Tunis, lived at 60, rue du Rendez-vous in the Bel Air neighborhood in the 12th district of Paris at the time of the 1936 census. He was married to Henriette, born in the Seine department in 1904. She was a saleswoman and he was a driver. In 1936, they had no children.

In the picture above, Élie looks happy and well-dressed. Might this have been for a wedding? Or for an important occasion?

Had the rise of anti-Semitism in France affected Élie and his family? Was he one of the victims?

In any case, in 1940, Élie’s name can be found on a military register: he had planned to do his National service. He had been issued with service number 3091, which indicates that everything was in place, ready for him to go. However, military service was suspended in 1940, and only reinstated in 1946, for a period of one year. He was thus prepared to defend his homeland. But on 10 May 1940, the Germans went on the offensive and put an end to the “phoney war” that had begun in September 1939. This period was so named because of the lack of hostilities, even though France had been at war for more than eight months. Until then, the French Military High Command had favored a defensive strategy: the Maginot Line. This was a fortified line built in France on the Belgian, German, Swiss and Italian borders. It was made up of underground tunnels linking the various battle stations, some of which were reinforced and equipped to hold machine guns and mortars.

Let us imagine what life was like for Élie at that time: as a Jewish French citizen, he must have felt safe from any danger. Like many French people, he had confidence in the army. However, when the German troops arrived on the outskirts of Paris, many Parisians fled, in order to escape. Is this true of the Sebag family, or did they stay in Paris? Did his whole family go into hiding during the war? Or did they try to continue living as they had “before the war”?

In addition, during the period of the German occupation, the Vichy regime enacted several laws concerning the status of the Jews, making them a separate category of the population. How might Élie have reacted to this?

May 14, 1941: The first mass round-up took place, involving Polish Jews, aged 18 to 40 and Czechoslovakian and Austrian Jews, aged 18 to 60. Did Élie feel safe because he was French?

May 28, 1941: Jewish-held bank accounts were frozen, and were now supervised by the Provisional Administrators’ Control Service.

June14, 1941: A German decree extended the coverage of the second German status of the Jews from the occupied zone only, to the free zone.

August 13, 1941: A German decree prohibited Jews from owning radios. In Paris, any such equipment had to be handed in at the Prefecture de Police or at district police stations by September 1, 1941 at the latest. Did Élie do this, or did he resist by hiding a radio in his home?

September 28, 1941: A German decree required any money from the sale of property confiscated from Jews during Aryanization to be paid to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (a French state holding account).

December 17, 1941: A German decree imposed a fine of one billion francs on the Jews, payable from the funds sequestered at the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations.

February 7,1942: A German decree imposed an 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew on Jews, and forbade them to move house.

March 27, 1942: In the Occupied zone, the German authorities deported the first convoy of Jews from the Compiègne camp. How much did Élie know about this? Did he have friends who had already been rounded up and sent to these camps? Did any of his relatives discuss it with him? How did he feel about it?

May 29, 1942: A German ordinance obliged all Jews over the age of six to wear the yellow star from June 7 onwards. Did Élie feel humiliated by this? Did he wear the yellow star? Or did he refuse to do so?

June 1942: The SS was given the order to seeking out and arresting all Jews.

July 12, 1942: The German Jewish Affairs Service, under the command of Theodor Dannecker, ordered that all Jews in the occupied zone be arrested.

July 16, 1942: The Vel d’Hiv roundup took place between July 16 and 17, 1942. It was the most extensive arrest of Jews in France of the Second World War, a mass roundup of foreign Jews in the occupied zone, who were then interned at the Velodrome d’Hiver (an indoor cycling track in Paris). More than 13,000 people were arrested, a third of whom were children, during this roundup. Did Élie know any of the people who were caught up in it? What did he think? Did his family feel threatened?

What happened to Élie him between then and 1944? How did he view the D-Day landings and the advance of the Allied troops towards Paris? According to witness statements, everyone celebrated this news on June 6, 1944, thinking that the war would soon be over, that the arrests would stop and that life would improve again. Did he become less cautious or stop paying attention?

On July 12, 1944, Élie was arrested by the French police, because he was Jewish. Had someone turned him in? Was he just stopped in the street? His name appears at number 12388 in the register of provisional consignment notes dated July 12, 1944 at 8 p.m. According to this register, he was arrested by officers of the Sub-Directorate for Jewish Affairs of the Directorate of the Judicial Police. He was transferred to the Drancy camp at 6 p.m. He arrived at the camp with twelve francs in his pocket. Some documents say that he lived at 10, rue Tourneux, while others mention his address as 11, impasse Tourneux. Had he moved from one to the other? Did he know he was in danger and therefore went to live in a small lane, where he would be less conspicuous? Had his family separated and spread out, so they wouldn’t be found together? Or was he already living with his brother Jules, a printer, in this dead-end lane?

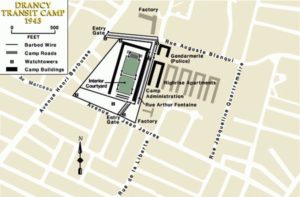

The Drancy camp, built in October 1939, was originally a to be housing estate called the Cité de la Muette, but it became an internment camp and then a transit area for Jews, who were held there before being sent to extermination centers. Nine out of ten Jews deported from France passed through the camp during the Holocaust, and almost 63,000 were deported from it. The last convoy left from Drancy and Compiègne on August 17, 1944.

Élie was interned in Drancy on July 13, 1944, the day before the Bastille Day. He spent 18 days there, in the men’s section. Was he able to notify his family? Did he receive any parcels from them? Did his brothers try to get him out? What was life like for him there? It was summer, so it must have been hot. The conditions were deplorable. Did he go up to the fourth floor so he could see the free people outside? What might he have been thinking? 18 days is a long time to wait, isn’t it? What did he think when he was told he was leaving on July 31, 1944? Did he think the Allies would arrive in time to rescue him? Élie left 17 days before the camp was liberated.

By way of information, in memory of this period, a memorial was built at Drancy in 1976 by Shlomo Selinger, who was himself deported, next to the Wagon-Témoin, (a memorial freight car), after he won an international competition. Then, in 1989, the Drancy Camp Historical Conservation Association was set up, and on May 25, 2001, Catherine Tasca, then Minister of Culture, signed an order placing the Cité de la Muette on the list of France’s protected monuments and sites.

In occupied territory, in France. Jews under arrest in Paris. Entrance to the camp, August 1941.

On July 31, 1944 Élie left Drancy camp aboard convoy 77, which was made up of 1310 men, women and children. 350 children, from just a few weeks to 18 years old, had been rounded up from Jewish children’s homes just a few days earlier, on the orders of Aloïs Bruner, the head of the Drancy camp, who was determined to fill up the convoy to capacity.

The journey lasted 4 days and 3 nights. The deportees were all crammed in together, with no space to sit or lie down. Living conditions were appalling.

They were fed before leaving but they had no supplies during the whole trip. There was just one water tank in each car, in which there were as many as a hundred people. To relieve themselves, they had one bucket in the middle of the car which was full up within an hour. It was very hot those few days, so they would have been very hungry and thirsty. What was Élie thinking during the journey? That he was going to work to help the German economy…

According to an account by Daniel Uberjetel, who was, like Élie, deported on Convoy 77, the arrival at Auschwitz was a terrible ordeal for both children and adults. When they got down from the cattle cars, in which they had spent several days, the Germans were waiting for them. They made what was known as a selection, sending the men to one side and the women, children and elderly people on the other.

Daniel Uberjetel also said that the 726 people in the left-hand line, including 271 children, must have been gassed that very day, given that there were more than 1,300 of them initially. Depending on their physical appearance, the prisoners were sent to forced labor or to the gas chambers, according to the decision of the SS. Why was Élie, who was only 24 years old, immediately gassed on August 5, 1944? He must have looked as if he was able for physical work. Perhaps he was sick, or perhaps he felt, after such a long trip, that the trucks waiting for them would be a good and easy means of going someplace else, even if he did not know where that might be. Élie, who should have been fit enough to work, unknowingly let himself be taken to the gas chambers. On the other hand, all the witness accounts suggest that he must have been able to smell the indescribable odor coming from the large chimneys that loomed in the darkness.

Those who were lucky enough to be selected for work underwent several processes. First of all, they were all brought together in a courtyard for a roll call. The next and most humiliating step was to strip naked in front of everyone else, then to be shaved and finally to be disinfected. After all these awful events, the Germans tattooed a number on their forearms, to symbolize that they had lost their identity. Finally, there was the distribution of striped “clothes” that were not necessarily their size, nor appropriate for them. Then they were given their “bowls”, which were a very precious commodity, needed to survive life in the camps. At that moment, they became DEPORTEES. Élie, however, was not so “lucky”.

Élie, like the others, was told that they were going to be disinfected in the “showers”. Using a very cruel trick, the Germans led them to believe that they were going to retrieve their belongings later, so they put their things in a locker bearing their number. Then the Nazi guards ordered them to go into the “showers”, often by insulting or beating them. They had to go in with their arms raised, so that as many people as possible could fit into the gas chambers. The more crowded it was, the faster the victims suffocated. The extermination was carried out using a gas called Zyklon B, a substance that had already been tested on Soviet prisoners of war. The doors of the room were locked and then the gas was poured in. As soon as the victims were dead, their gold teeth were pulled out and the women’s hair was sheared by groups of Jews, known as the Sonderkommando, who were assigned to work in the crematoriums. The bodies were thrown into the ovens to be cremated, and then the bones were pulverized and the ashes scattered in the fields.

Thus, Élie Sebag left this world ashes, like more than a million others in Auschwitz. His body could never be found, and he could never be laid to rest by his family, just as the Nazis had planned. He seems, however, to be the only one of his family to have been deported. His name alone is on the wall of deportees’ names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

At the end of the war, his brothers undoubtedly went to the Hotel Lutécia to try to locate him, but in vain.

In 1946, his brother, André Sebag, tried to reclaim the house where Élie had lived. Then, in 1961, his other brother, Jules Sebag, the printer who still lived at 11, impasse Tourneux, near rue Tourneux, began researching his brother Élie to find out what had really happened to him. He also tried to claim compensation, but this was refused because he was only the brother of the victim. Jules does not appear to have been married.

We have been unable to find any living relatives of Élie Sebag. We would very much have liked to find people close to him, who would have known him, to try to put the whole puzzle together, and to find traces of him that the Germans were so eager to erase. The Covid 19 lockdown did not help either: we should have gone to Drancy to better understand the sites and the living conditions there and our teachers had intended to go to the Paris Archives office. And unfortunately, not everything is available to read online on the Internet…. However, by working with what we did manage to find and with the help of the Convoy 77 Association, we tried to undo the destructive work of the Nazis and to give “life” back to a stranger who might otherwise have been totally forgotten. In this way, we tried to fulfil our duty to remember.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Bravo à vous pour cette recherche ! Je suis passionné de généalogie et étudie la communauté juive de Sfax, en Tunisie et celle des Sebag dans ce pays (ma mère est née Sebag).

Je suis la petite fille de Marcelle sebag qui me parlait souvent de son frère disparu après le veld’hiv . Je suis très émue par cette recherche et j’ai informé les deux enfants de Marcelle qui sont mes oncles , de ce travail fait par des élèves et leur professeurs .

Vous parlez du frère de ma grand mère . Elle me parlait souvent de ce frère disparu après la rafle du veld’hiv.

Épouvantable période que mes oncles Huet (catholiques convaincus) ont combattue, pendant des années.

Très cordialement

Bertrand Ogerau-Solacroup