Sami BITNER

This biography was written the 9th grade students from the Collège Les Blés d’Or high school in Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, with the help of their History and French teachers, Ms. Garillière and Ms. Jorrion. The research and analysis work was started before the Covid 19 lockdown but the biography was written during the lockdown.

Since there are no photographs of Sami Bitner, we are showing a map of Romania with his supposed place of birth, Giurgiu, which is named after St. George.

Before the war

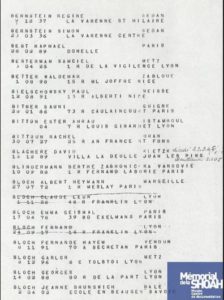

Sami Bitner was born on January 28, 1886 probably in Giurgiu, Romania, not far from the capital, Bucharest. However, before discovering that he was born in Romania, we firmly believed that he was from Guignes, in Seine-et-Marne department of France, as this is what it said on Convoy 77’s list. As we are in the Seine-et-Marne, we had a point of reference, but it turned out that this was not the case when the town hall of Guignes replied to say that his birth was not mentioned in their registers on that date. According to certain other historical documents, he was born either in Bucharest or in Giurgiu.

Sami was the child of Loupain Bitner and Caroline Satainfeld, and since he was Romanian, we can assume that his parents were too. However, the surnames of both the mother and father suggest to us that they came from Eastern Europe.

Unfortunately, we were unable to find any photos of Sami Bitner.

When did he decide to leave Romania to come to France? When did he arrive in France? We found him on the 1926 population census in Paris. Did he arrive with his parents when he was younger, or as an adult and, in that case, was he alone or accompanied by someone else? It’s hard to tell! We were unable to find out during our research.

He lived in Paris, at 73, rue Caulaincourt in the 18th district, in the Montmartre quarter. For many years, the building was home to various different artists. The famous painter, Auguste Renoir, lived at number 73, rue Caulaincourt around 1902-1903. At the same time, it was also the home of the Swiss painter, draughtsman and lithographer Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, who died there on December 13, 1923. The painter couple, Jules Pascin and Hermine David, also lived at the same address in the 1920s. Sami may have known them if he had already arrived in Paris at that time. Census records of the building show that musicians, pianists and the conductor of an orchestra also lived there.

He lived in Paris, at 73, rue Caulaincourt in the 18th district, in the Montmartre quarter. For many years, the building was home to various different artists. The famous painter, Auguste Renoir, lived at number 73, rue Caulaincourt around 1902-1903. At the same time, it was also the home of the Swiss painter, draughtsman and lithographer Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, who died there on December 13, 1923. The painter couple, Jules Pascin and Hermine David, also lived at the same address in the 1920s. Sami may have known them if he had already arrived in Paris at that time. Census records of the building show that musicians, pianists and the conductor of an orchestra also lived there.

His girlfriend’s name was Alphonsine Guglielmazzi. She was born on August 8, 1892 and died on February 16, 1972. She was a seamstress and Sami Bitner was a ladies’ tailor, employed by the firm Etzenman. He was illiterate. They lived with Alphonsine’s mother, Hortense, who was a waistcoat maker and then a button-maker for a time. She was born in 1869 and her surname was Bourgeois. They had always lived together as a couple but had no children. As for his partner’s family, her brothers had died. The first, Maurice, died during the First World War before getting married and the other, Jules, had no descendants either, so we could not even track down any distant relatives.

During the war

How did Sami Bitner react when the war started? Did he feel safe in a country steeped in human rights? Did he join the exodus, like the thousands of other Parisians who fled when the Germans arrived? How did he react to the first anti-Jewish policies?

As soon as they arrived, the German authorities put in place a number of anti-Jewish measures. The first, in July 1940, was a degree which banned Jews from practicing certain professional occupation, such as teaching, civil service work, journalism, business management, etc. They had no freedom. Jews had to hand in their bicycles, were not allowed to take the tram, to ride in buses or even to travel in a private car. Jews could only go to a Jewish hairdresser. They were not allowed to go out in the streets from eight o’clock in the evening until six in the morning. They could not go to theatres, cinemas, other entertainment venues, the swimming pool, or to go to play tennis or other sports. They could not play games in public. They were not allowed out in their own gardens after 8pm and were not allowed to visit Christians. Jewish children had to go to Jewish schools. And on top of all these rules, the Jews absolutely HAD to wear the yellow star.

Sami must have felt very humiliated. How might he have reacted? Did he wear the yellow star or did he refuse to do so? Did he live as a recluse, at home? Or did he still travel to work in full view of everyone, or did he try to remain hidden?

Then there were the roundups, starting with the “billet vert” roundup on May 14, 1941, so named after a green postcard that summoned foreign Jews to present themselves to the police. How did Sami escape this? Why was he not arrested? Was he warned not to come forward? Then there was the Velodrome d’Hiver, or “Vel d’Hiv” round-up that took place on July 16 and 17, 1942, when Jews were interned in a winter cycling stadium. Was he in hiding? Again, had he been warned? This was the largest mass arrest of Jews in France, carried out with the help of the French police. 13,152 Jews were arrested in total, most of whom were foreign or stateless Jews. The Germans were afraid that Jews, especially foreigners and Jews from Eastern Europe, would be able to plan attacks against them. Those arrested were held in the stadium for almost five days, without food or water, before being deported to the Auschwitz camp via Beaume-la-Rolande and Pithiviers. Only small number of adults, (less than a hundred), managed to escape.

Since the Nazis’ goal was to round up all the Jews to get rid of them, many more roundups took place. We think that Sami must have felt more in danger at this time than he ever had before, and that once the roundups were over, he must have felt fortunate and perhaps unworthy to have survived when so many others had disappeared and there was no news of them. Before being able to resume an almost “normal” life, Sami must have lived in a state of absolute dread, fearing that at every street corner an SS or a member of the French police would stop him, putting an end to the opportunity he had been given to survive.

In addition, during the German occupation, life was awful for the citizens, partly because of the bombing, but more importantly, it was hard to feed themselves due to rationing. There were 5 different types of ration coupons, all based on age group. Coupon E, for example, for children of up to 3 years old, allowed for hardly any food at all. The J1 coupon was for children between 3 and 6 years old. The J2 coupon was for children aged 6 to 14, which accounted for a lot of children, given the difference between the minimum and maximum ages. Coupon J3, for young people between 14 and 21 years old, was the ticket that allowed the most food for children. Coupon A was for those over 21 years of age and coupon V was for older people above retirement age. Certain items, such as coffee, had completely disappeared and cooking oil was only available on the black market. The black market was used to buy extra rations at very high prices. How did Sami manage to feed himself? Was he able to live a decent life? It must have been his girlfriend who did the shopping.

At any rate, until July 1944 Sami managed to stay alive and a free man.

When the Normandy landings took place on June 6, 1944 and the objective of the Allies (the United States, Great Britain, Free French forces and Canada) was to open a new front to relieve the Russians, the French believed it meant the beginning of the liberation of France. According to witness accounts, everyone was expecting victory. Sami must have felt relieved. Did he then become less vigilant? Did he start going out into the streets more? Or did he continue to live a quiet life, in the knowledge that the constant harassment would soon be over?

Sami’s arrest and the camps

Sami Bitner was arrested on July 18, 1944 at his workplace at 10, rue Henner, in Paris, where he worked as a ladies’ tailor. He signed his statement at the police station at 11 p.m. and was sent to the Drancy camp the next day at 6 p.m. This round-up, which can indeed be referred to as a round-up because according to the register of statements several Jews were arrested that day on grounds of their “race”, had been ordered by an SS officer called Aloïs Brunner. He was in charge of the Drancy camp, and took advantage of the confusion to continue his murderous madness and to take revenge against a plot to assassinate Hitler that had taken place a few days earlier.

On his arrest record is written “Den Juden Bitner Sami”, as if he was called that every day on the streets. How humiliating! But on that day, he surely believed that with the Allies on the outskirts of Paris, he and the other prisoners might be released very shortly. Yet at the same time, arriving in Drancy was one step closer to death. It should be borne in mind that Sami left the camp on July 31, 1944; Drancy was liberated on August 18, 1944 and Paris on the 25th!!

Living conditions in Drancy were deplorable. Sami arrived at the camp with a significant sum of money, 646 francs, which he had to hand over as soon as he entered the camp. He is then put in the section where the men lived. They were placed in large buildings with unacceptable sanitary conditions. Did he know any other people there? Did he meet up with any of his friends? He stayed there from July 19 to 31. 12 days, just waiting… waiting for Aloïs Bruner to have enough people to fill his convoy. 12 days of seeing more people arriving every day, 12 days of not knowing, maybe hoping to find a way out. Waiting for to be liberated by the Allies, perhaps? Did he manage to send a letter to his partner, given that he was illiterate? Did his partner manage to send him a parcel via the Union Générale des Israelites de France (Union of French Jews) organization before he left??

During the night of July 22, 1944, Aloïs Brunner ordered the arrest of all Jewish children placed in orphanages run by the Vichy government on the orders of the Germans, to fill his convoy. They arrested more than 300 children, including 18 infants and 217 children between the ages of 1 and 14. Sami must have seen them in the camp the very next day. What must he have said to himself?

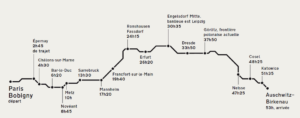

At 6 o’clock in the morning on July 31, 1944, 1310 men, women and children left Drancy from the nearby station at Bobigny. Convoy 77 left for Auschwitz, where it arrived on August 3. Drancy is over 900 miles (1500 km) from the extermination camp. Under SS supervision, the deportees, including Sami Bitner, boarded the train with their luggage and spent the journey in deplorable conditions. They had no opportunity to lie down or even sit down, given the number of deportees crammed into the same cattle car (between 60 and 100 people). There was only one bucket in the middle of the wagon for them to relieve themselves in full view of everyone else, and it rapidly filled up and overflowed. The journey lasted four days, during which they could not eat when they were hungry, wash themselves or breathe fresh air. They had no idea where they were being taken other than it was often referred to as “Pitchipoï”. Sometimes they could see the name of a train station, so they understood that they were being taken to the East. It was the height of summer and extremely hot. They had nothing to drink, so were dehydrated. The oldest and weakest of them died before they even reached the camp.

At 6 o’clock in the morning on July 31, 1944, 1310 men, women and children left Drancy from the nearby station at Bobigny. Convoy 77 left for Auschwitz, where it arrived on August 3. Drancy is over 900 miles (1500 km) from the extermination camp. Under SS supervision, the deportees, including Sami Bitner, boarded the train with their luggage and spent the journey in deplorable conditions. They had no opportunity to lie down or even sit down, given the number of deportees crammed into the same cattle car (between 60 and 100 people). There was only one bucket in the middle of the wagon for them to relieve themselves in full view of everyone else, and it rapidly filled up and overflowed. The journey lasted four days, during which they could not eat when they were hungry, wash themselves or breathe fresh air. They had no idea where they were being taken other than it was often referred to as “Pitchipoï”. Sometimes they could see the name of a train station, so they understood that they were being taken to the East. It was the height of summer and extremely hot. They had nothing to drink, so were dehydrated. The oldest and weakest of them died before they even reached the camp.

Website garededeportation.bobigny.fr

When they arrived on August 3, 1944, in the middle of the night, Sami and the others were relieved to see the train stop alongside a platform. The Germans opened the doors of the car shouting “Alle runter!!” which meant “Everybody off!!”. Any hope of an end to the humiliation would have been immediately swept away by the dreadful smell (they probably had no idea it was the smell of burnt flesh), the macabre appearance of the camp, the barking of the dogs and the shouting of orders. As soon as they got off the train, the deportees were subjected to the “selection” process. They were separated into two lines by the German SS, who threatened them with truncheons. The men were sent to one side and the women and children to the other. The oldest, the youngest and the pregnant women, who were deemed unfit for work, were sent straight to the gas chambers. This is probably what happened to Sami Bitner, who was 58 years old. The other 846 deportees were destined for forced labor. 291 men and 183 women were selected for this work. Did Sami get into one of the trucks that were to take them “to the showers”? Or did he follow on foot? Did he understand what was happening to him?

Accompanied by an orchestra, including Jewish musicians who were forced to play music, the deportees made their way confidently to the gas chambers. An evil trick! Then they had to undress in a room near the gas chambers and leave their belongings on coat racks, thinking that they would get them back after the shower. Was Sami fooled? Or did he know that his end had come? Naked and frightened, they entered the gas chambers with varying degrees of confidence and waited for the water to come out of the shower heads. Instead, the gas, which was called “Zyklon B”, was released. It took between 6 to 20 minutes for them to die.

And that is how Sami Bitner died. He never had a chance. In 1945, only 93 men and 157 women from Convoy 77 were still alive.

When Alphonsine Guglielmazzi, Sami’s girlfriend, saw that her partner still had not returned home by the end of the war, she began searching for him. She must have gone to the Hotel Lutecia (a hotel used as a meeting place for returnees and their families) very soon after the war ended. She began to take the necessary steps to prove that he was dead. Her research and all the administrative formalities took several decades until finally, in the 1960s, she received an annuity as compensation for Sami Bitner’s death.

Today, all that remains of Sami is his name, engraved on the wall of deportees’ names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

The following photos are taken from the film “Schindler’s List”. They show how the deportees’ suitcases were sorted. They bear witness to so many lives stolen or destroyed and so many identities erased. This is one of the problems we face when we try to reconstruct the life stories of these deportees. Their lives, identities and memories were deliberately stolen by the Nazis because that was exactly what they wanted; to erase all traces of Jewish life. This is the problem we encountered in putting together Sami’s biography.

Français

Français Polski

Polski