Fanny LIBERS

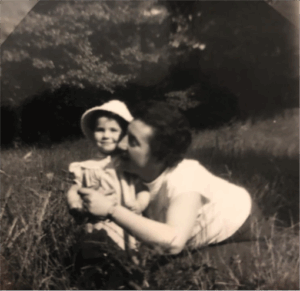

Photo of Fanny – date unknown – Family archives

We are a group of ten 9th grade students from class 3e B at the La Cerisaie middle school in Charenton-le-Pont, in the Val-de-Marne department of France. With the guidance of our History and Geography teacher, Nathalie Baron, we compiled Fanny Libers’ biography from material provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, as well as other records found during our research. We were also fortunate enough to make contact with Sophie de Juvigny, Berthe and Fanny Libers’ great-niece, who kindly shared some invaluable information and documentation relating to her aunts.

The first part of Fanny’s biography is similar to that of her sister Berthe, which is also featured on the Convoy 77 website.

This biography was written by Alice Bitot, Adrien Dabrowski-Richard, Yasmine Dahbi, Arianny De Jesus Rodrigues, Melvil Gautier, Valentin Le Flem, Ewan Martin, Jeanne Ossedat, Eliott Ploix and Lucie Roussel, with the guidance of Nathalie Baron.

I – The Libers family: from Russia to Paris

Berthe’s father, Leib was born in Vladimir, near Moscow in Russia, on October 10, 1874. His parents, who came from a town called Loudsky, were Isaac, a carpenter, and Sarah Thanis, who did work. Her mother, Esther Fetz was born on June 1, 1881 in Równo (now Rivne in Ukraine, having previously been ruled by Russia and Poland). Esther’s father, Yakov, ran a store and also took care of one of the town’s synagogues and her mother, Socia, did not work. The family was Jewish.

Esther was the oldest of 4 or 5 children. She never went to school and spoke only Yiddish, a Germanic language spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. Her family must have been fairly poor, because she began working in a bakery when she was just 8 years old, delivering bread to customers each morning. When she grew up, Esther opened a little tea room opposite a large school in the Christian quarter of Równo.

Esther’s marriage to Leib would have been arranged by her father. The couple went on to have a daughter, who died shortly after she was born, and then another, Chiffra, who was born in Równo on December 25, 1903.

Leib emigrated to Paris first, on his own, in 1904. Esther and their daughter Chiffra joined him later. He probably left Russia to avoid the compulsory 7-year military service, which had been introduced at the start of the war between Russia and Japan, which lasted from February 8, 1904 to September 5, 1905. In addition, pogroms happened often in their area. These were attacks on the Jewish community, often including looting and murder.

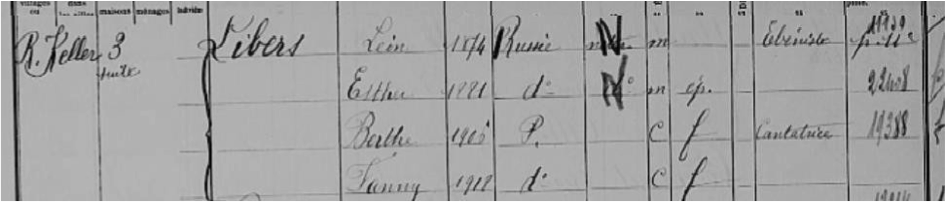

Their marriage certificate, issued at the town hall in the 11th district of Paris on August 26, 1914, reveals that they were then living at 3 rue Keller in the Bastille neighborhood. It was not far from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which had long been Paris’s main furniture manufacturing and sales district.

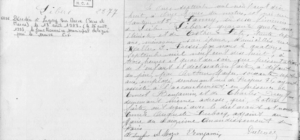

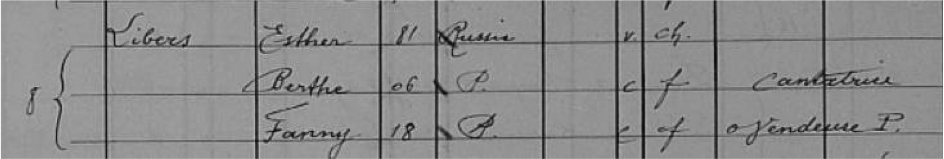

Berthe was born in Paris on June 28, 1906, and her sister, Fanny on September 11, 1918.

Berthe’s birth certificate – Paris archives – 11N 329

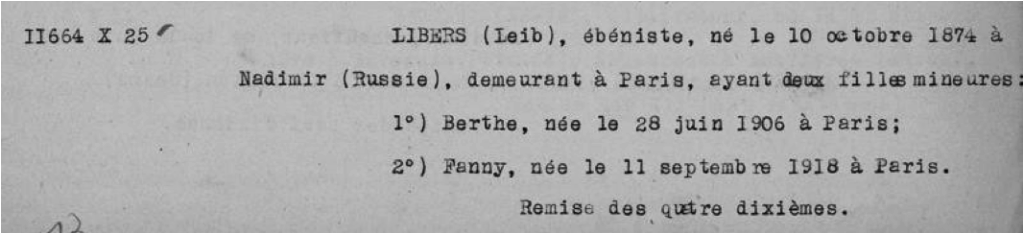

In August 1914, Leib, who had been using the name Léon since he arrived in France, tried to join the French Foreign Legion, which had been made possible by a decree dated August 3, 1914. However, he was rejected because he was unable to find a uniform to fit him. However, his willingness to enlist meant that he and Esther were able to apply for French nationality, which was granted on September 4, 1926.

As a result, Berthe and Fanny also became French citizens, but Chiffra, because she was born in Russia, was ineligible and thus remained stateless.

A page from the naturalization register – French National archives

According to memories passed down through the family, Léon was a strict father but at the same time very affectionate towards his daughters, who he wanted to raise in the best way possible.

He had learned the French language, was able to read the newspaper and was interested in politics. He was very grateful to France and the French people for making him welcome and enabling him to live freely, in a tolerant society.

Esther, on the other hand, found it harder to integrate, and felt isolated. She learned to speak French with her daughters, little by little, but never mastered reading and writing it.

She kept in touch with her father regularly, corresponding with him in Yiddish. Before the First World War began in 1914, she would take Chiffra and Berthe back to Równo during the summer recess. From 1911 to 1914, Esther’s brother Elie came to live with them in Paris, where he studied medicine.

Léon, Esther, Chiffra, Berthe and Fanny in the 1920s (Family archives)

A piece of furniture made by Léon (Family archives)

Having no doubt learned the trade from his father, Léon opened a cabinet-making workshop at 58 rue de Charonne. He produced fine furniture featuring marquetry made of exotic hardwoods and bronze. The family has preserved some of these pieces, including the chest of drawers in the photo above.

Léon’s sold his furniture cheaply and his wife did not work, so the family’s income was quite low. In October 1934, Léon, then aged 60, died of pneumonia at the Broussais hospital in Paris.

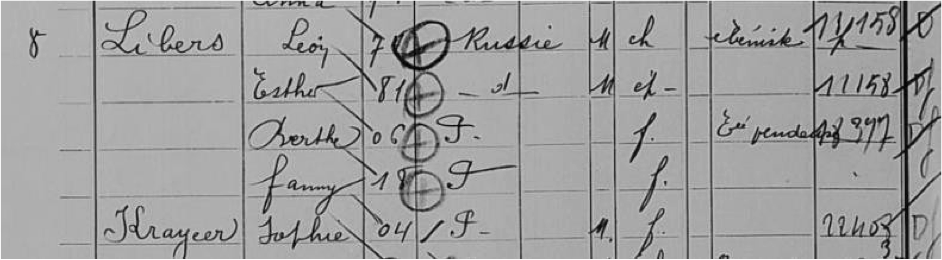

By that time, Chiffra, who went by the name of Sophie, had probably left home. She was still listed with family in the 1926 census under her married name, Krajcer, but was no longer there

1926 census listing for 3 rue Keller – Paris archives

1931 census listing for 3 rue Keller – Paris archives

Sophie (Chiffra) married a man called Simon Krajcer and the couple had two daughters, Léa and Annette, who were born in Paris in 1927 and 1929. The family lived at 10 rue de Sévigné in the 4th district of Paris.

After the war, Sophie’s younger daughter, Annette, wrote a lot about her what had happened to her family. Her daughter, Sophie de Juvigny, kindly shared her stories with us. Annette Krajcer-Janin died on January 23, 2024 in Avignon, in the Vaucluse department of France.

Sophie Krajcer and her daughters, Annette and Léa

(Source: the Cercil-Musée Mémorial du Vel d’Hiv (Study and research center on the Loiret internment camps -Vel d’Hiv memorial museum) Facebook page)

II – Life before the war

Despite their financial difficulties, Léon and Esther were keen for their daughters to get a good education. For example, Fanny and her sisters took violin, piano and singing lessons.

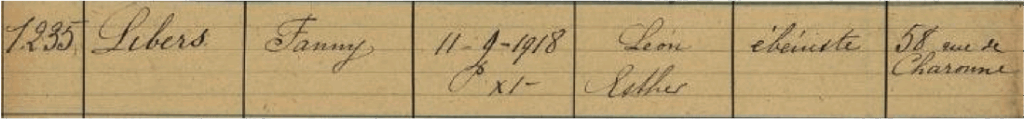

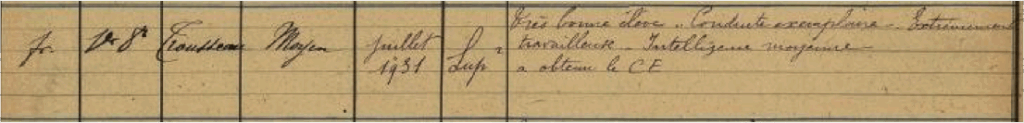

We were able to find some records about Fanny’s education, including a school register, which was probably not intended to be shared with parents on account of the rather blunt assessments it contained, about Fanny and other pupils.

The comments on Fanny read: “Very good student. Exemplary behavior. Extremely hard worker. Average intelligence. Passed the C.E.” (Elementary school certificate)

School register – Paris archives

The address listed in the register is 58 rue de Charonne, which was Léon’s workshop, rather than their home. Fanny left the Trousseau school in July 1931 at the age of 13, having passed her elementary school certificate. We do not know if she went on to junior high school, nor if she ever went to the school on rue Keller, which was just across the street from their apartment building.

The apartment building at 3 rue Keller, in the 11th district of Paris (photo taken by Nathalie Baron)

The 1936 census lists Fanny as a saleswoman. She was 18 at the time. In 1940, when the government introduced a series of anti-Semitic laws, she found casual home-based jobs such as sewing and peeling vegetables.

1936 census

Unfortunately, we have no records relating to Fanny’s life between the start of the war and when she was arrested. Her Drancy internment record states that she had been working as a clerk.

According to her niece Annette, prior to the outbreak of war, Fanny and Berthe used to sing at the synagogue in Neuilly, but she was 20 by that time, and must have had other hobbies and interests too.

III – Arrest and deportation

Fanny was arrested at the same time as her sister Berthe. They were arrested at home, at 3 rue Keller, on June 17, 1944, most likely because the Germans had discovered that Berthe was a member of the “Plutus” Resistance network. Berthe’s biography includes more details about this.

We do not know if Fanny, as well as Berthe, was involved in the Resistance, but if she was, she made no mention it after the war. She would surely have been aware of her sister’s activities, however.

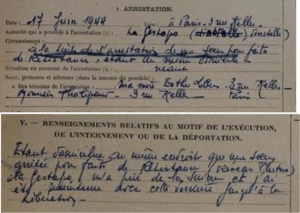

Extracts from Fanny’s file at the French Defense Historical service archives in Caen, dated November 1951

Berthe’s account of the deportation, dated June 4, 1945, provides us with some details about the sisters’ arrest and deportation. Together with the letters Berthe wrote to request that she be recognized as a deported Resistance fighter rather than a political deportee, it helped us retrace their journey. Berthe makes very little mention of her sister Fanny, although they remained together throughout their ordeal. We also used information gathered by Annette Krajcer-Janin, passed on to us from her daughter, Sophie.

After they were arrested, Berthe and Fanny were taken to the Gestapo headquarters at 11 rue des Saussaies in the 8th district of Paris. There they were interrogated for three weeks before being transferred to the political prisoners’ wing of Fresnes prison, where they were put in cell 440. They remained there from June 17 to July 10, 1944. Berthe said in one of her letters that she had been tortured, but we do not know if this is also true of Fanny.

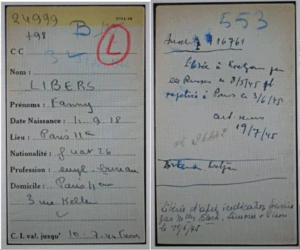

From there, on July 10, they were transferred to Drancy internment camp, north of Paris. According to the Drancy records, Fanny and Berthe were assigned consecutive serial numbers, 24,998 and 24,999 and sent to a room on the third floor of building 3.

Drancy camp records. The fact that Fanny’s Drancy internment record card is yellow means she could be deported immediately. The red L, which was added after she returned to France, means that she had been liberated from the camps, as do some of the notes on the back of the card – Shoah Memorial, Paris

On July 31, 1944, the sisters were deported from Bobigny station to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. Berthe stated that they travelled in a cattle car with around 60 deportees.

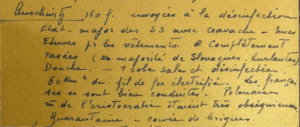

They arrived in Birkenau in the early hours of August 3. The SS immediately carried out the selection, and sorted the deportees who were to be sent to the gas chambers from those who were to go into the camp for forced labor. During the selection, Berthe and Fanny were separated from each other. In the end, however, the SS man sent them both to the group chosen to work in the concentration camp.

In her account of the deportation, Berthe explained what happened to the women who were selected to work: “160 women were taken for disinfection by an S.S. unit with riding crops. Clothes put in steam ovens. Shaved all over, showered, given one dirty dress and disinfected.”

Fanny had the serial number A-16761 tattooed on her forearm. She had to learn it off by heart and be ready to say it in German, because during her time in Auschwitz, her identity was reduced to just a letter and some numbers.

Berthe later stated that she was assigned to “brick tasks” but we know nothing more about what that involved exactly. Did Fanny and Berthe stay in the same barracks and were they forced to do the same hard labor? Again, we do not know.

Extract of Berthe’s account of the deportation – June 18, 1945 (French National archives)

On October 29, 1944, along with some other women, the sisters were transferred from Auschwitz to the Kratzau camp in Czechoslovakia, which had recently become annexed to the Gross-Rosen camp in Poland.

They traveled from Birkenau to Kratzau by train, a hundred at a time in cattle cars, and the journey time was very long. Régine Jacubert, another Convoy 77 survivor, said in a recorded testimony “It took us two days to travel 250 kilometers [155 miles]”.

Kratzau was a forced labor camp, with strict rules. The women slept in barrack huts lined with three-level wooden bunks. Sanitary conditions were awful, and according to Régine Jacubert, “the body lice were fatter than we were”.

The work at the factory was not only very hard, but the women worked twelve-hour shifts. Fanny was on her feet the whole time, with no breaks, suffering from the cold, and had her hands submerged in oil as she was making ammunition. The women were worked barefoot, wearing just wooden sandals, and were dressed in rags. Nevertheless, Fanny managed to keep going, both physically and mentally. She wounded her shin at one point, and had a purple scar on her leg all her life, as she used to massage it with her hands, which were ingrained with oil and never washed.

The French women, of which there were just over a hundred, helped each other out in various ways, especially by protecting each other from the Polish and Hungarian kapos, who constantly threatened and often beat them.

Berthe had to be admitted to the infirmary as she was unable to work due to having oedema in her legs. According to their niece, Annette, Fanny used to visit Berthe to cheer her up, and sometimes picked dandelion leaves on her way back from work to give Berthe a little extra nourishment.

The only consolation for the women who were sent to Kratzau was that there were no regular selections there, so no risk of being sent to the gas chambers. Most of the women who survived the Holocaust after being deported on Convoy 77 were sent to Kratzau for forced labor.

In the spring of 1945, the Soviet army and a group of Czech resistance fighters liberated the camp, but they did nothing to help the deportees. The Germans had deserted the site a few days earlier, leaving the women to their own devices.

A short time later, some American soldiers arrived and began to help the remaining prisoners.

Berthe was taken by ambulance to a hospital in a nearby town, and the nuns there took in and cared for Fanny.

The sisters were then able to travel home to France together, by train, alongside some French prisoners of war. Berthe, who was very weak and still unable to walk, was carried on a stretcher or pushed in a wheelchair. They crossed the border near Mézières, and then arrived at the Lutétia Hotel in Paris, which had previously been taken over and used by the Germans, but between April and August 1945 it was used as repatriation centre for large numbers of deportees from the Nazi concentration camps. In total, some 18,000 people were repatriated to this prestigious hotel, which General De Gaulle had ordered to be requisitioned.

IV- Fanny’s arrival in France

When she first arrived back in France, Fanny, who was 5’4” tall, weighed just 125 pounds. In common with most of the women survivors, her periods had stopped. The doctor who examined her deemed her to be in good health overall, but then she tested positive for typhus, a life-threatening disease that can be carried by head lice, body lice, fleas or ticks. Fanny was admitted to the Claude-Bernard hospital in the 18th district of Paris, where she stayed for around two weeks. She then went back to live at their old apartment at 3, rue Keller, with Berthe, their mother and their nieces, Léa and Annette Krajcer, who stayed with them for a year or so.

In late 1941, the girls’ father, Simon, had been assigned to a foreign workers’ group in the Ardennes region. He thus survived the war but sadly their mother, Sophie, did not. She was deported in 1942, after all three of them had been arrested during the Vel d’Hiv roundup on July 16, 1942, and taken to the Pithiviers camp in the Loiret department of France. The girls were then transferred to Drancy internment camp. Thanks to a cousin who worked in the Drancy camp office, the girls were saved and, as children of foreign Jews, they were taken in by the UGIF, where Berthe worked. They were then sent to live in hiding.

Fanny went on to work for the Sétamil lingerie company, which was founded in 1916 and later became the well-known brand Etam. She then became a sales representative, selling buttons to the haberdashery trade. In January 1955, she received a lump sum of 13,200 francs as a type of compensation for the fact that she had been deported.

Fanny remained single for the rest of her life. It is hard to say if she had any personal relationships. She continued to live with her mother at 3 rue Keller until her mother died in June 1958.

Sophie de Juvigny has fond memories of “Aunt Fanny”, who she found somewhat eccentric and unpredictable. Fanny often went to see Sophie’s parents, who were her only close family in Paris.

In addition, after the war, Fanny suffered from depression and was diagnosed as bipolar, probably due to the psychological after-effects of being deported. As a result, she was hospitalized 2 or 3 times a year, and had to undergo some rather drastic psychiatric procedures, such as electroconvulsive therapy.

In 1954, Fanny was officially granted the status of « political deportee », but she never spoke to her family about what she had been through during the war.

Fanny died of a brain abscess in Lagny, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, on August 18, 1993.

Fanny Libers and her great-niece Sophie, in around 1958 (Family archives)

References to records used to compile Fanny Libers’ biography

- Leib and Esther’s marriage certificate – Paris archives – 11M 463

- Leib Libers naturalization application – French National archives – 11664 X 25

- Esther Fetz’s naturalization certificate – French National archives – BB/34/457

- Fanny’s birth certificate – Paris archives – 12N 287

- Paris census records – 1926 : D2M8 254 – 1931 : D2M8 397 – 1936 : D2M8 589

- School register – Paris archives – 2615W_14_Libers

- Berthe’s account of the deportation – AN F9 5586

- Libers Fanny © French National archives in Pierrefitte: F/9/5712

- Libers Fanny © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 564 387

- Libers Fanny 3.3.2 TD File_Bad_Arolsen_104984948_0_1

- Entretiens INA. Mémoires de la Shoah, Régine Jacubert.

We would like to express our warmest thanks to Sophie de Juvigny, who kindly shared some invaluable information about her family, and to the Convoy 77 non-profit association team, who helped us with our research.

Français

Français Polski

Polski